Throggs Neck, in the southeastern corner of the Bronx, sits on a peninsula that juts out into the East River. The Bruckner Boulevard and the neighborhood of County Club to the North are the peninsula’s only terrestrial borders. Its position at the junction of Long Island Sound and the East River made it a logical place to build Fort Schuyler which was completed in 1856. Schuyler, along with Fort Totten across the river in Bayside Queens, provided a formidable defense against any ships attempting to approach the city from the North.

Land of Peace

Most New Yorkers would be hard pressed to tell you where the neighborhood’s name comes from. While Throgg may sound like some sort of phonaesthetic medieval punishment, its origins can be traced back to John Throckmorton, a Puritan who came over from England with minister Roger Williams to escape religious persecution. Throckmorton had followed Williams first to Massachusetts and then Providence before breaking off on his own and settling on the peninsula (neck) of land in the Bronx that the Dutch called Vriedlandt or "Land of Peace”.

In 1642, Director-General of New Netherland Willem Kieft granted Throckmorton a patent on the land originally inhabited by the Siwanoy tribe. Unfortunately for Throckmorton, this turned out to be a terrible time to move into the neighborhood.

In the fall of 1643, in one of the opening salvos of what would be known as Kieft's War, 1,500 Wappinger and Lenape Indians descended upon New Amsterdam, destroying homes and farms and killing the majority of the English settlers. It was around this point that the settlers must have realized why the Dutch had been so eager to give them large swaths of land on the edge of their colony. Anne Hutchinson, of Hutchinson River and Co-op City fame, was killed in the raid as was much of Throckmorton’s family. Luckily for Throckmorton, a passing ship was in the area, and he was able to escape.

Nothing But a “G” Thang

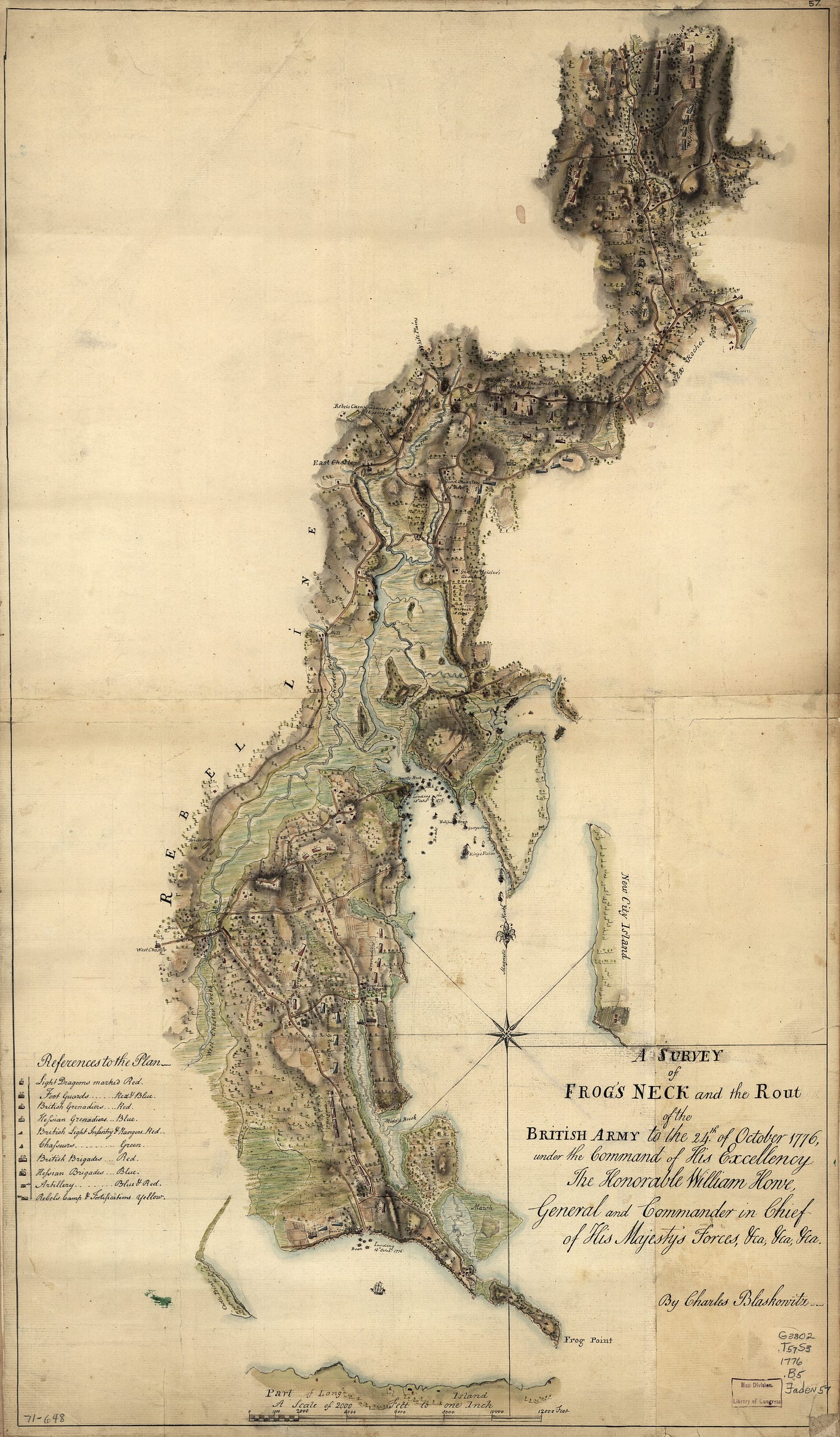

How Throck got changed to Throg or Throgg, not to mention what happened to the Morton, is up for debate. It does seem however that for quite a long time the whole area was known as Frog’s Neck.

At some point, someone must have pointed out the biological absurdity of the name, and Frog’s was changed to Throg(g)s.

It is a remarkable example of how few generations it takes to corrupt a good old name. Some spell it with a double 'g,' the average native calls it 'Frog's Neck,' and a very large percentage of New Yorkers have not the faintest idea of its origin.1

Today you will see the name spelled with both the single G and the double G, with the more substantial Throgg being favored by locals. Many attribute the name’s pruning to Robert Moses who, perhaps wanting to show neighborhoods weren’t the only thing he could sever, christened the newly completed Throgs Neck Bridge with a single G.

Some say Moses thought Throg would be easier to spell though a more apocryphal version of events claims Moses shortened the name because of the money he could save on sign paint.

I found references to the single G Throgs Neck as far back as 1860, so I think Moses may be getting a little too much credit here. Whatever the reason, much like Boro(ugh) Park, the continued usage of both spellings throughout the neighborhood will be sure to confuse people for years to come.

GGATED COMMUNITIES

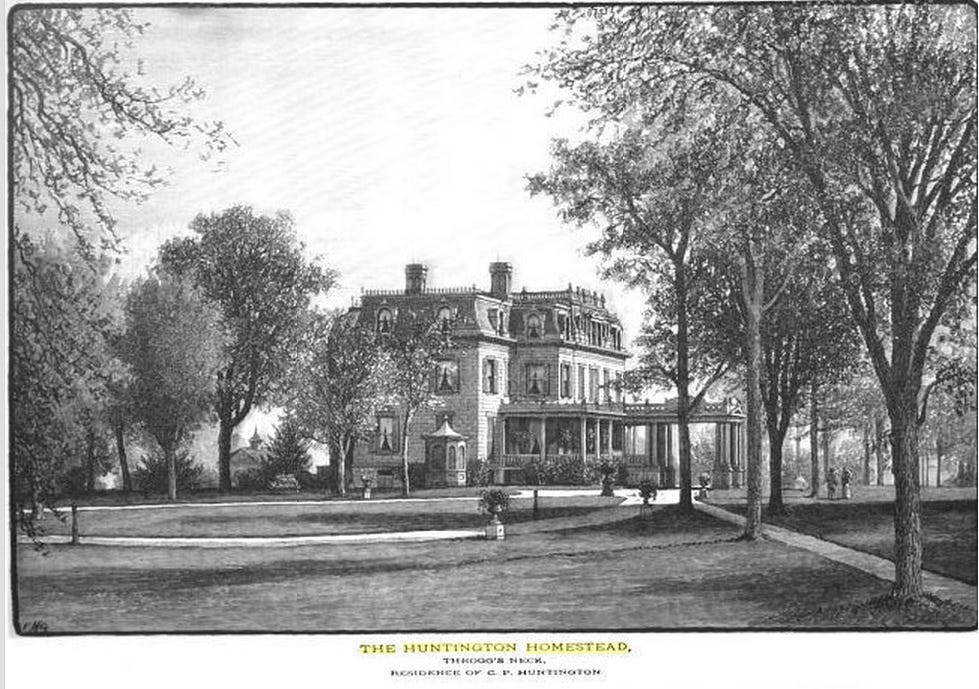

When I last visited Throggs Neck, I began my trip at Schurz Ave, a short road that parallels the East River shoreline. The most prominent building in the area belongs to Preston High School, a Catholic high school for girls. The building dates from 1840 when it was constructed as a summer home by Frederick Christian Havemeyer, who called it Beau Rivage. The Havemeyers were sugar barons who, at the beginning of the 20th century, controlled ninety-eight percent of sugar production in the United States. Havemeyer sold it to railroad mogul Collis P. Huntington, who renamed it the Huntington Homestead.

Along the way, I passed a couple of modest private clubs like the Redwood Club and Sokol Orel, which houses the American Bohemian Gymnastics Society.

Soon, I came to a stretch of road fronted by a 6-foot iron fence. Through the bars, I could make out neat rows of small houses and handmade wooden street signs, backlit by the sunlight reflecting off the East River flowing just behind. I rounded the corner to get a better look, but I could see the fence, now a faux tawny stone, encircled the whole perimeter of the enclave.

When I got home and looked up the area, I learned that it was called Silver Beach Gardens, a private housing cooperative where residents own their homes but lease the land from the collective. To buy a house there, you have to have three Silver Beach residents vouch for you. More interesting, to me at least, was the revelation that in the late 1700s, a fellow named Edward Stephenson owned a farm that encompassed most of the Throggs Neck peninsula.

While I was pretty sure I didn’t have any relatives who owned large farms in the Bronx, it still seemed like a lead worth pursuing. At the very least, it might get me past security.

I quickly googled Stephenson+Farm+Bronx, but, much to my surprise, the search returned my own pictures, images from a project I had done on urban farming several years ago.

Unable to learn more about these Bronx Stephensons, I looked into the man who purchased the farm from them, Abijah Hammond, a pretty interesting guy in his own right. Abijah was an artillery officer in the Revolutionary War before becoming one of the biggest real estate investors in New York. He was a director of the Bank of New York and best friends with Alexander Hamilton, serving as one of the pallbearers at his funeral.

Hammond was also one of the main players behind the pig wars of the 1810s. At his urging, several hundred prominent New Yorkers signed a petition to remove all “free-running” pigs from the city, of which there were said to be approximately 20,000. Their complaint alleged that gangs of rouge hogs caused carriages to tip over, crashed into pedestrians, and destroyed the streets as they rooted around for something to eat. The petition failed to move the needle, however, as the porcine population proved pretty popular, serving as both sanitation force and food supply for a good portion of the city.

The Hammond Mansion, built in 1795, is used as an office today by the Silver Beach Gardens association.

EDGEWATER

There is actually a second private gated community in Throggs Neck, Edgewater Park, on the northeast tip of the neighborhood. In the early 20th century, Richard Shaw bought the plot of land and permitted church groups, Boy Scouts, and workers from the city to pitch tents and build simple tarp-covered cottages on the water’s edge. During the Great Depression, many of those tents and cottages were converted into year-round domiciles.

In 1986, the Shaw family sold the property to the existing tenants, and Edgewater Park, like Silver Beach Gardens, became a cooperative community. Residents, who were able to pay roughly $8,000, could buy a stake in the neighborhood.

In 2010, both Edgewater and Silver Beach Gardens were accused in a federal lawsuit of using racial discrimination to keep Black families out.

IF YOU GOT THE HOLE, YOU GOT THE GOLD.

If you have taken the Whitestone Bridge from Queens into The Bronx anytime in the last decade, you have undoubtedly seen the undulating expanse of green and gold fescue tufted mounds that make up Trump Links.

Just in case it wasn’t clear who owned the course, the name TRUMP LINKS was embossed in the giant green berm that emerges from the golf club’s parking lot.

Show me someone without an ego, and I'll show you a loser

― Donald Trump

This area was a landfill up until the mid-1960s, "a popular place to illegally dump cars, oil drums and other refuse.”2 Robert Moses was the first person to propose a golf course on the site in the 1950s, but planning for the Jack Nicklaus-designed course began in earnest under Rudy Giuliani in the 1990s.

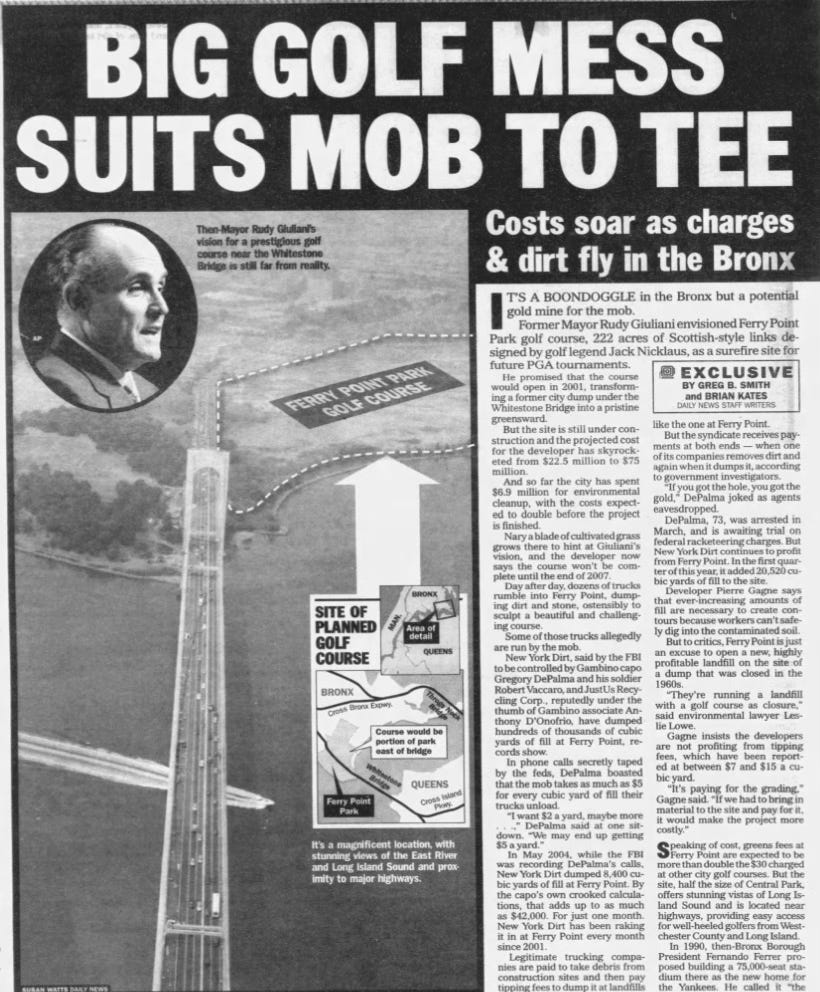

Originally scheduled to open in 2001, the course, dubbed the “boondoggle in the Bronx” encountered numerous setbacks due to lax oversight and the extensive cleanup required for the site that was full of arsenic, lead and methane gas.

When the original developers, Ferry Point Partners, were fired in 2006, not a single blade of grass had been planted. A city audit found that the parks department had paid $7.24 million for cleanup work that should only have cost $1.26 million. Some of that money went to New York Dirt, a Gambino family venture that had trucked in hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of fill, receiving up to $5 per cubic yard for the privilege. Normally, trucking companies are paid to pick up debris and charged to offload it, but in this case, they were getting paid on both ends prompting Gambino associate Gregory DePalma to say, “if you got the hole, you got the gold.”

The project ended up costing city taxpayers over $127 million, orders of magnitude higher than the original $22.5 million budget. With the city desperate to get the project off the ground, Trump was given an exceedingly favorable deal, promising to build a clubhouse and pay for course upkeep while the city covered the water and sewer costs. For the first five years, he could keep all of the club’s earnings.

Just a couple of months ago, on the final day of Trump’s civil fraud trial, the Bally’s Corporation assumed control of the remaining eleven years of the golf course lease. They wasted no time in covering the Trump berm with an enormous green BALLY LINKS tarp. If it is successful in its bid for one of three pending New York City casino licenses, Bally’s plans to use the site to build a casino.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio starts at the waterside in Edgewater Park and then features some particularly dulcet chimes I came across, interspersed with an edited portion of my epic conversation with long-time Throggs Neck resident Jimmy.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

Patrick J. Cashin spent 20 years as the photographer for the New York State Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). He has shot for Newsweek and photographed for the Naval Reserve and for the Air National Guard as a Master Sergeant.

Here is his stunning picture of a falcon flying above the Throgs Neck Bridge, taken while on assignment photographing the tagging of new falcon chicks. More of Patrick’s work can be seen on his site.

NOTES

Speaking of Animals with no necks, there is a Reddit group for it: Animals with no Necks

Warhammer Fantasy Battle is a tabletop miniature wargame where people collect and assemble miniature models and interact with them according to some set of rules that I’m not going to try to explain or figure out. Maybe we have some “hammerheads” out there?

The game has been around since 1983 and looks similar to the way my friends and I tried to play Dungeons and Dragons in the 5th grade, completely ignoring the rules and making up stories for the little figurines, crashing them into each other and occasionally talking about charisma points, whatever those were.

Anyway, I mention it because in the game, there is a character named Throgg (two g’s) who is the Troll King. He is “possessed of a grim and malevolent cunning. Under his dominion, the creatures of the hinterlands have united into a vast army, and soon, the race of Man shall feel the Troll King’s wrath.”

It doesn’t get much more metal than that.

Unless, of course, you’re talking about the 80s metal band Anthrax. Two members of the band, Drummer Charlie Benante and bass player Frank Bello, grew up in Throggs Neck.

In case you observe, Sept. 14th is officially Anthrax Day in the Bronx.

Old Roads from the Heart of New York: Journeys Today by Ways of Yesterday, Within Thirty Miles. Sarah Comstock 1913

https://citylimits.org/2001/09/01/no-fore-warning/

Another great post and, as ever, each photog(g)raph feels like it deserves its own story.

Had to Google “phonaesthetic.” Good word!