Borough Park in Brooklyn is between Kensington, Bensonhurst, and Sunset Park. Its borders are Ninth Avenue to the west, McDonald and 21st Avenues to the east, Greenwood Cemetery to the north, and 60th Street to the south. Most people who live there eschew the "ugh," preferring the diminutive designation Boro Park.

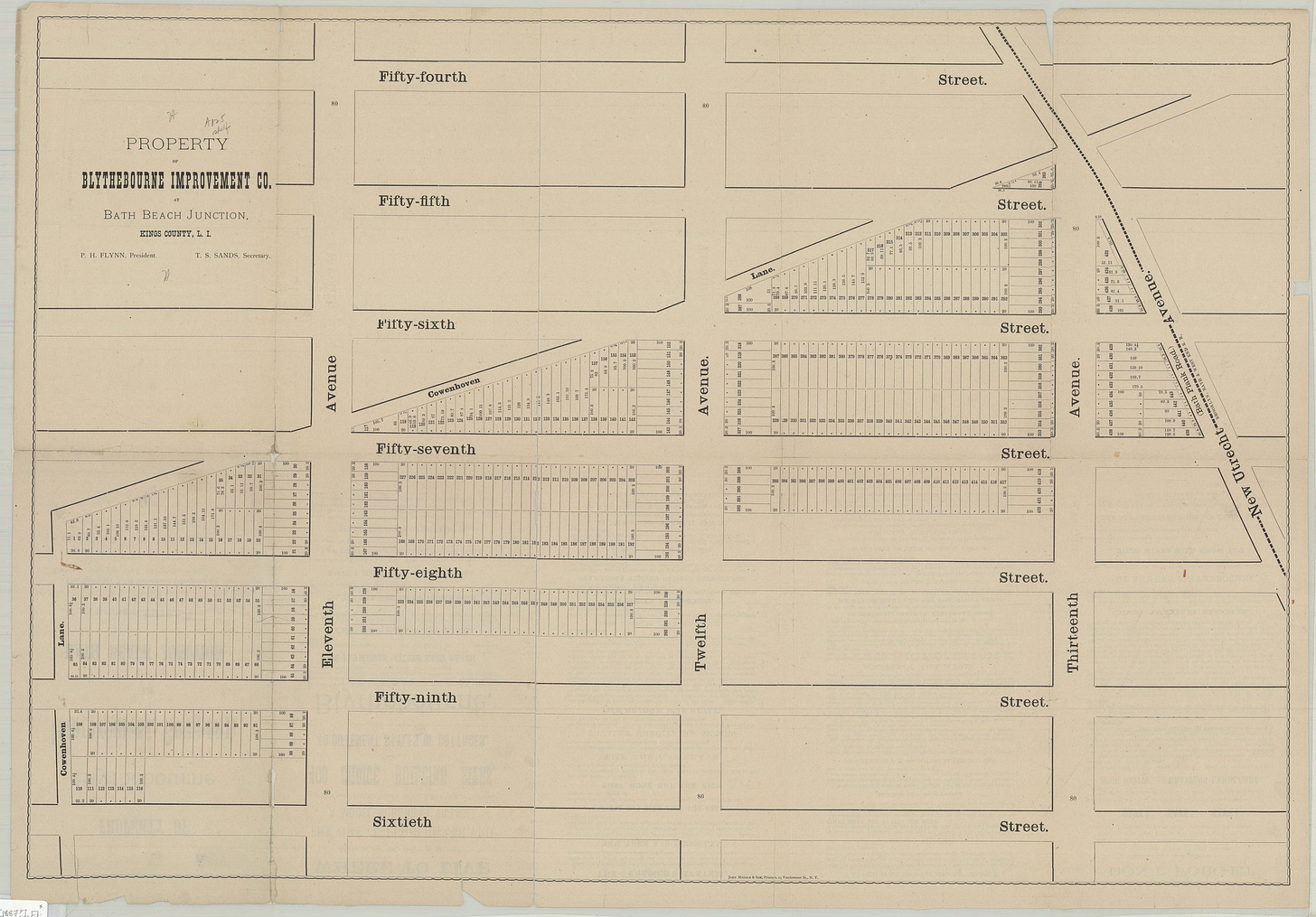

The land that encompasses the neighborhood was colonized by Dutch settlers in 1652 as part of New Utrecht, the last of the original six towns founded in Kings County. It remained farmland until 1887 when Electus B. Litchfield purchased a large parcel and built a cottage community he called Blythebourne, meaning "happy home" in Scottish.

It sounds like the original residents of Blythebourne had a grand time in their happy home, throwing stag parties at the dance hall before their wives "queered" them out.

The neighborhood’s volunteer firefighters, perhaps spending too much time at the dance hall, were known for their ineptitude. The best thing anyone could say about them was that they “saved the chimney of every house they ever worked on.”

While it may seem harsh to critique volunteer firefighters, the fact that the water tower they used as a home base burned down may indicate that their reputation was warranted.

The firefighters had a rivalry with a nearby department, and if both arrived at the scene of a fire simultaneously, they would “shoot water all over each other” instead of the fire they had been summoned to put out. In what must have been a particularly memorable day, somebody thought it would be funny to stick a hose down a "Feller's Pants" until the water shot out from his collar.

In 1902, William Reynolds, a mega-developer who also founded Prospect Heights and built the short-lived Dreamland amusement park in Coney Island, bought Blythebourne and much of the surrounding land, subdividing it for housing. Despite the absence of any actual park, Reynolds renamed the neighborhood Borough Park, marketing it as a suburban escape, a respite from the noise and dirt of the city—the lots sold like hotcakes.

After WWI, the elevated train replaced the Brooklyn, Bath, and Coney Island Railroad steam line that had previously served the area, and the newly accessible neighborhood experienced rapid growth. Several apartment buildings went up, and Jewish transplants from the Lower East Side and Williamsburg began to fill them.

Around this time, Blytehbourne was wholly incorporated into Borough Park. Today, the only evidence of its existence is the post office, which, despite being the one place where geographical accuracy would seem to be a practical necessity, retains the old Blythebourne name.

After WWII, the neighborhood, which, up to that point, had been roughly half Modern Orthodox Jewish and half Italian and Irish, experienced a large influx of Hasidic Jews.

The construction of the BQE in the 50s led to yet another wave of settlement in the neighborhood. To build his expressway, Robert Moses destroyed ten of Williamsburg’s most populated blocks, cleaving the neighborhood of Orthodox Jews, Italians, Poles, and Russians in two. High-rise apartments were built to replace the destroyed homes, but with the Orthodox provision against using electricity on Shabbos, many of the displaced chose to move to Boro Park, where elevator buildings were few and far between.

Distorting the Envelope

Today, the neighborhood is home to one of the largest Orthodox and Haredi Jewish communities outside Israel. With 27.9 births per 1,000 residents, Boro Park has the highest birth rate in New York City. Maimonides Medical Center, which serves the neighborhood, delivers more babies than any other hospital in the state.

In 1992, to accommodate the rapidly growing population, the city created a special zoning district halving the footage required for setbacks and rear yards.

Buildings in the neighborhood have been extensively modified, their fronts pushed out and their tops pushed up. Urban planners call these architectural transmogrifications, ''distorting the housing envelope.”1

A sort of architectural grafting is common in Boro Park, where an additional two or three floors sprout from the roof as if extruded from the existing building.

Some newer homes have been built by merging adjacent lots. These new homes, oversized edifices looming above their neighbors, are like townhouses on steroids, purpose-built to accommodate the large families that average nearly seven children each.

The Roof is on Fire

My kids are on spring break this week, so I wanted to get out and photograph early to have enough pictures before leaving town for a few days. After pressing send on last week’s newsletter, I quickly packed up my gear, trying not to think about all the typos I had just unleashed into the world and headed out to photograph.

It was one of those bracing end-of-winter days, the sky a cloudless deep blue that is the bane of most photographers’ existence, but I had a deadline, and the weekend forecast predicted torrential rains. My initial destination was Sunset Park, but after spending 20 minutes fruitlessly looking for parking, I continued eastward, ending up in Boro Park instead.

Eventually, I found my way onto 13th Ave, the commercial spine of the neighborhood, lined with Jewish bakeries, bookstores, and wig shops. The streets were packed; it felt like walking through midtown at rush hour with the addition of scores of kids whizzing by on scooters, their tzitzits flying behind them as they careened recklessly down the crowded sidewalks.

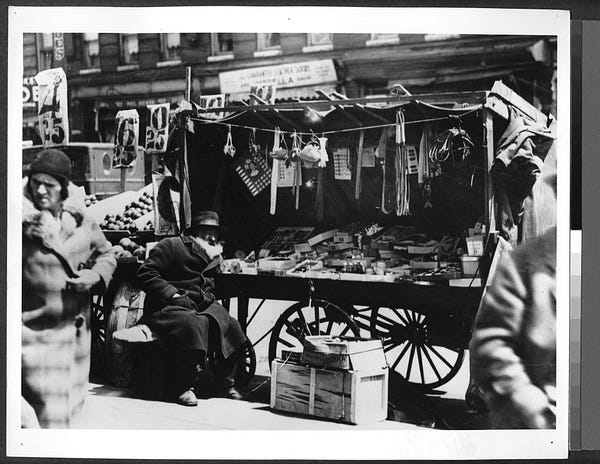

In the early 20th century, 13th Avenue was lined with pushcart vendors and picklemen hawking their barrels of half sours. Then, in the 1930s, as part of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s "war on pushcarts," the city moved vendors to an indoor public market.

On my visit, the pushcarts had been replaced by yellow busses and minivans, double and sometimes triple-parked. As I made my way down the street, the already considerable cacophony intensified as a peal of fire engine sirens harmonized with the ceaseless chorus of car horns. The traffic-choked streets came to a standstill, and the once blue skies started to dim, the air gradually filling with an acrid haze of smoke.

I followed a phalanx of scooter-borne kids furiously hurtling toward the source of the smoke.

By the time I got there, the streets were packed, hundreds of curious onlookers massing at the foot of a three-story home as firefighters ascended a ladder to the building’s burning roof.

Fortunately, the Boro Park firefighters proved much more competent than their predecessors, and the roofer whose blowtorch had caused the fire required only minor medical attention. Unfortunately, nobody tried to stick a hose down another feller’s pants.

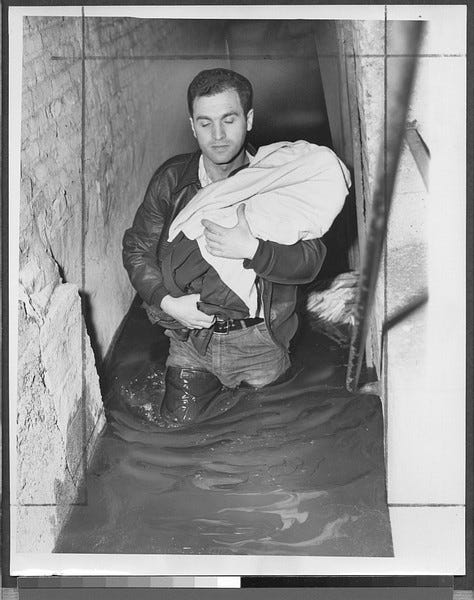

When looking for archival images from the neighborhood, I came across this image of the aftermath of a fire in 1952 that happened just one block away. The photo is captioned: Water damage: Michael DeFilippo carries his year-old daughter, Carol Anne, out of the basement apartment at 1145 47th.

A few days later, DeFilippo issued a plea for new housing in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, having been forced to move into his mother Rose’s apartment with his wife and daughter.

COVID

According to the city’s health department, in early October 2020, more than 8% of Boro Park residents tested positive for COVID-19 compared with 1.65% citywide. This prompted then Governor Cuomo to ban mass gatherings, capping attendance at houses of worship at 25% of capacity and with no more than ten people. The ban caused riots in the streets of Boro Park, with large groups of mostly young men and boys setting fires and burning masks along 13th Avenue.

A 34-year-old Hasidic man, Berish Getz, who was standing recording video, was branded a moser, or traitor, and was beaten unconscious and taken to nearby Maimonides hospital.

Zach Helfand from the New Yorker wrote an excellent article on the protests and the neighborhood’s reaction to the pandemic restrictions here.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s recording starts under the elevated train, passes through a crowded kosher supermarket, and then moves to the scene of the aforementioned fire on 46th St. The audio tour finishes with a symphony of hammers, drills, and chop saws, familiar sounds in the neighborhood that has been issued more permits for private construction projects than any other in Brooklyn.

Last weekend was Purim, the Jewish holiday that resembles Halloween, at least in terms of wacky costuming. In one of the world’s most Jewish neighborhoods outside of Tel Aviv, a place that draws families from throughout the city and beyond, Purim would seem like the perfect day to spend walking around and taking photographs.

Of course, I had no idea it was Purim until the day after, so there will be no evidence of that in the following pictures.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I first saw Gianni Cipriano’s project, In The Land of Black Coats, in 2007 when it was featured in the now-defunct NY Times photo series The City Visible. Several of Gianni’s moody black-and-white photos show scenes from an Orthodox wedding taken in and outside one of the oldest synagogues in the neighborhood, Young Israel Beth El of Boro Park.

Gianni’s ongoing project, Politico, is a fantastic body of work that documents the

”Ruthlessness, ambition, fantasy and failure,” of Italian politics.

NOTES

While there are over 300 synagogues in Boro Park, there are plenty of other houses of worship around. One of the more impressive buildings is the Precious Blood Monastery at 5324 Fort Hamilton Parkway.

Built in 1908, the monastery is occupied by the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood. The monastery is big enough that the sisters share it with another coterie of nuns with a far less metal-sounding name, the Servants of the Lord and the Virgin of Matará.

.

In honor of the upcoming solar eclipse, here is a gallery of men watching a solar eclipse in Boro Park in 2017. The photographer is credited simply as JDN. I would buy a book of these.

Out of 256 reviews on Google, the Blythbourne Post Office gets an aggregate score of 1.9 stars. Allegations of illegal check cashing and having to bribe the manager for service are sprinkled among the typical complaints of horrible wait times and overworked and disinterested employees.

While a post office branch with negative reviews is hardly surprising, what makes the Blythbourne office unique is that it has been getting panned by its critics since the late 1800s. This Brooklyn Daily Eagle article details complaints about the post office losing and failing to deliver mail from as far back as 1892.

https://www.nytimes.com/1998/01/07/nyregion/orthodox-neighborhood-reshapes-itself.html?ugrp=c&unlocked_article_code=1.f00.ITS2.bb4BkqWBdcDX&smid=url-share

such an interesting post - thank you so much Rob! You know I am big fan of your substack - one of the most precious things about it besides your amazing photos is your audio- I love clicking that first and then reading the post. It really puts you in there. Thank you!!!

Thanks Rob. Fascinating as always.

I recently visited boro park on a friday afternoon, to witness the mayhem ahead of Shabbat. Minor flaw in my plan-- I brought my dog for a walk. Walking towards 13th avenue from the F train, I noticed that nearly everyone was going out of their way leaving the sidewalk and walking in the street, instead of walking past me. Once I got to the main avenue, I realized that almost all of the kids were terrified of my dog! My 20 pound dachshund chihuahua mix! I kept him on a very short leash and eventually picked him up and carried him. Some parents lifted babies out of stroller and said (in Hebrew) "Look, dog!"

I asked an older man on the street what was up with that, and he explained that a certain understanding of the Torah forbids owning a pet, since God intends you to love other humans, not animals. So (according to him) 99% of kids in the neighborhood have never seen a dog and wouldn't know the difference between a dog and a cat. I never would've known!