Today, Co‐op City is neither the purgatory nor the heaven that its critics and champions predicted. It is a functioning community. Only New York—a city of 8 million snobs, skeptics, and desperate survivors—could have swallowed a new town of this size within its limits without a ripple. Anywhere else in the world, there would be a steady stream of visitors to see how a community of 45,000‐going‐on‐60,000 takes shape.

Ada Louise Huxtable

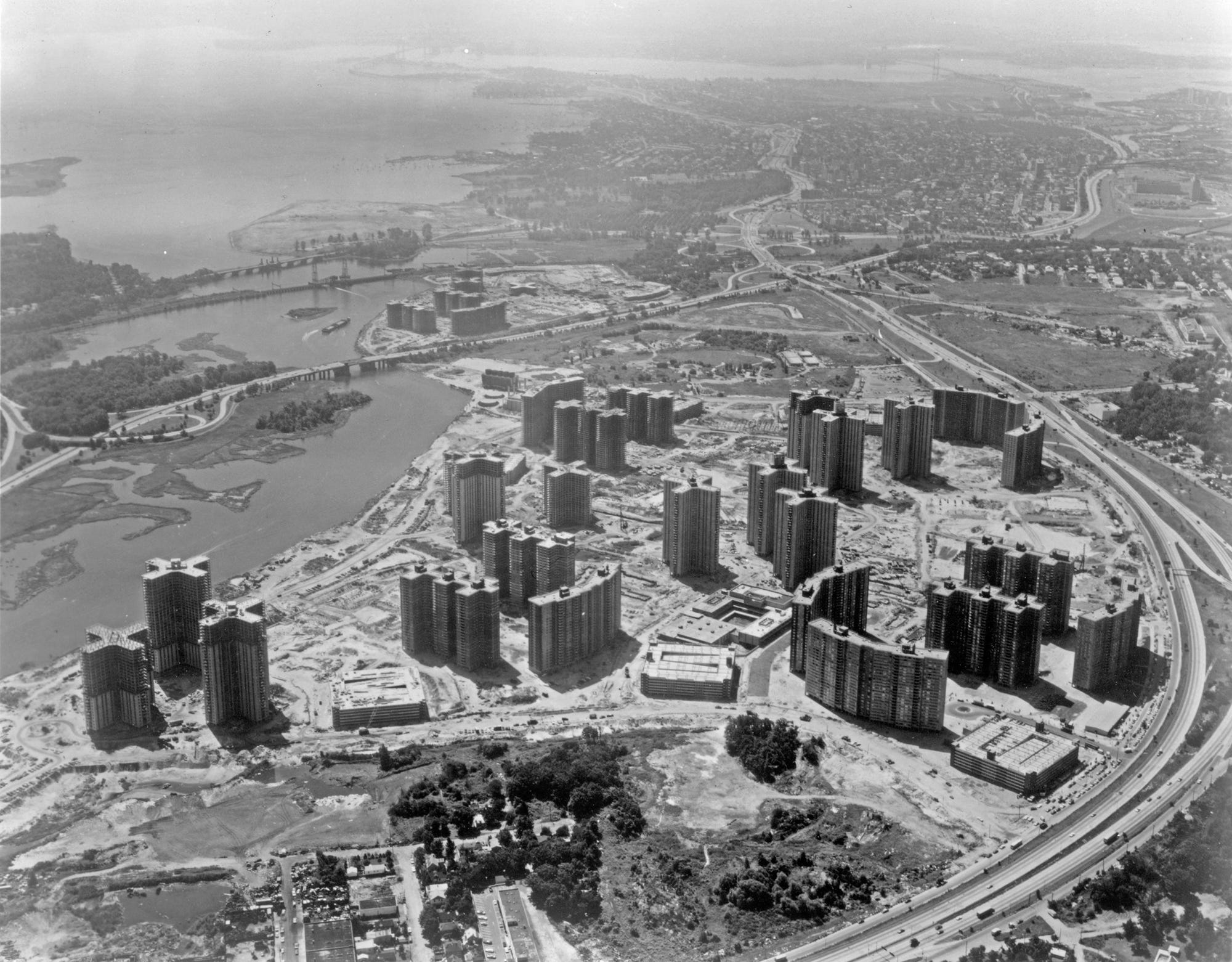

When driving into the city via I-95 or the Hutchinson River Parkway, the very first thing you will see is Co-op City, 35 dun-colored megaliths rising out of the marshes of the Northern Bronx. Completed in 1973, this “city within in a city” has 15,372 apartments, around 70,000 rooms and is home to over 45,000 residents, down from 60,000 at its peak. It is the largest cooperative apartment complex ever built. It’s also the world’s largest NORC (Naturally Occurring Retirement Community).

The neighborhood is served by three shopping centers, six schools, 15 houses of worship, two newspapers, and a police force. It even has its own Comic-Con. There is everything you could need, which is good because it is a hard place to get to and out of. Residents are optimistic that will soon change as a $2.8 billion retrofitting of an existing Amtrak route along the Hells Gate line will connect the area to Penn Station.

SPLIT ROCK

Co-op City is built on infilled marshland. Years before the arrival of the Dutch settlers, the Siwanoy tribe harvested shellfish from the tidal flats of the Hutchinson River. The river gets its name from Anne Hutchinson, an excommunicated religious leader from Massachusetts who, along with six of her children, was massacred by the Siwanoy, casualties of an ill-advised war started by then Director-General of New Netherland, William Kieft.

If you are so inclined, you can visit the site of the massacre, Split Rock, where, as legend goes, Anne and her daughter Susanna unsuccessfully tried to hide during the Siwanoy attack. The rock itself is located on a triangle between the New England Thruway and the Hutchinson River Parkway.

A couple of years ago, emboldened by a new idea of photographing natural sites of historic NYC importance, I decided to pay the area a visit. I stood at the edge of the on-ramp with my camera and tripod, waiting for a lull in the traffic. Soon I saw my opportunity, hopped the guardrail, and sprinted across the road. Having narrowly cheated death, I was rewarded with this magnificent view.

I walked around the site a few times to see if there was maybe a more interesting angle or something that somehow conveyed a sense of the rock’s dark history. There was not.

The plaque commemorating Anne Hutchinson and her family, like the one on Jack Kerouac’s former home in Ozone Park, is gone. Maybe I’ll start a new project on stolen historical markers instead.

JUST THE PLACE

The marshland surrounding Split Rock remained largely off the radar until 1927 when Harry W. Mitchel crashed his plane into an elm tree on Eastchester Creek.

Emerging from the wreckage, the Panglossian Mitchel deemed the desolate parcel of marshland “just the place” for a new airport.

The country’s largest aviation firm, the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, agreed. Not content to just build planes, they also wanted to get into the airport business and purchased the vacant lot with the intention of turning it into ”the premier flying field in the world.” Their plans were grounded, however, by the onset of the Great Depression, which forced them to abandon the project. When the New York Municipal Airport - soon to be Laguardia - was completed in 1939 in East Elmhurst Queens, any hope of building an international airport in the Bronx would be extinguished.

For the next few years, the area was used as farmland.

In his fantastic piece on Co-op City for the New Yorker, Ian Frasier interviewed Ken Migliorelli, a Hudson Valley farmer whose half-gallon jugs of cider are ubiquitous at today's city farmers’ markets. Migliorelli recounted the workers building I-95 pausing to let his father harvest his dandelion crop just before bulldozing the land.2

A lot of the Co-op City site, Ken Migliorelli recalls, was more or less squatters' land, where anybody who wanted to could farm. Marshy streams ran through it, some navigable by canoe.

At some point, in a bit of synergistic genius that the Curtiss-Wright company could only dream of, some of the land was occupied by both a cucumber farm and a pickle factory.

FREEDOMLAND

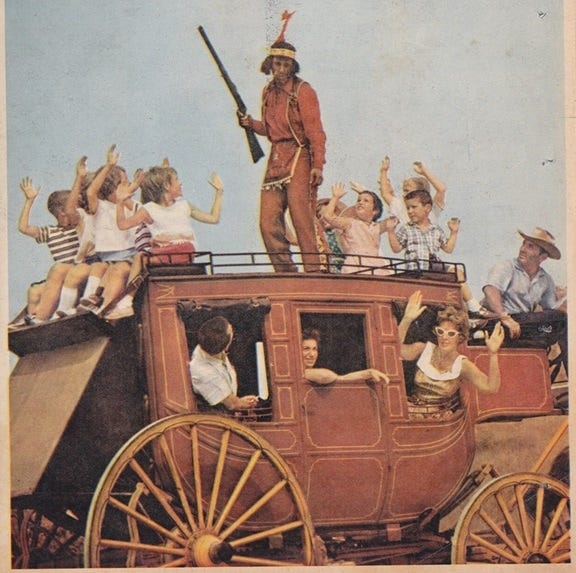

For a short four years, 1960-1964, the marshland on the banks of the Hutchinson River was transformed by Cornelius Vanderbilt Wood Jr into what was billed as the “Disneyland of the East.”

Cornelius, known as C.V. or Woody to his friends, was instrumental in the planning, construction, and management of Disneyland in California, but he rubbed the Disney brothers the wrong way and found himself banished from the Magic Kingdom.

Woody, who, among other accomplishments, was a champion trick roper and two-time chili cook-off world champion, would go on to build a better, more historically accurate amusement park (because nothing is more amusing than historical accuracy), and he would call that park FREEDOMLAND USA.

The park, financed by the Donald Trump of his day, real estate mogul William Zeckendorf, was laid out in the shape of the lower 48 states and divided into several different US locations and time periods like San Francisco - 1906, The Old Southwest - 1890, and Chicago - 1871.

Out of a cloud of dust and thundering hoofbeats in the Bronx yesterday rode two cowboys, four showgirls, a bulldozer ballet and a posse of press agents—all hired to publicize what they called the “greatest outdoor entertainment center in the history of man.”

This excerpt is from Gay Talese's coverage of the park’s groundbreaking ceremony in 1959 for the New York Times. He goes on to describe the elaborate buffet with seventy gallons of lemonade, 150 loaves of French bread, sixty pounds of ham, and eight turkeys, though much of the food would go to waste:

Not counting the publicists and official backers, only nineteen spectators sat in the grandstand listening to the speeches. Six were Brooklyn Girl Scouts, seven were Bronx Boy Scouts. When asked why they had come, the Boy Scout troop leader said: “Our Scoutmaster sent us."

The shortage of enthusiasm for the park’s groundbreaking presaged Freedomland’s future troubles as it never drew the kinds of crowds needed to turn a profit. This could be partly blamed on the lack of traditional rides like roller coasters and bumper cars. Instead, you could go to The Bank of New York – an actual bank branch that featured an exhibit about currency or ride the Mule-Go-Round – a merry-go-round pulled by mules.

Another popular attraction was Borden’s Barn Boudoir, which featured a fully furnished apartment for the Borden dairy mascot, Elsie the Cow.

If the barn triggered an attack of hay fever, you could head to The Old Apothecary Shop, where everyone got a free sample of the decongestant Coricidin. Better yet, at the Continental Casualty insurance exhibit, you could learn about a variety of different insurance policies and buy a $10,000 accidental death policy for just a quarter.

The park’s most popular attraction, where that accidental death policy could have come in handy, was The Great Chicago Fire. Every 20 minutes, a gas-fueled fire engulfed the facade of a building, and children were allowed to help put out the fire by operating a water pumping station.

It turns out that roller coaster rides are more popular than free decongestant and in 1964, Freedomland declared bankruptcy. The park was razed to the ground.

The only tangible reminder of the park’s existence is this small rock, in the shadow of Bagels On Bartow, inlaid with a (still intact) plaque memorializing its history.

Some, including William Zeckendorf, say Freedomland was just a “device to hold the land, "3 a way to expedite building permits by proving the swamp was safe to build on.

UHF

The United Housing Foundation (UHF), established by the "father of U.S. cooperative housing," Abraham Kazan, was responsible for 23 cooperative housing projects in NYC, and they would take advantage of the newly enacted Mitchell-Lama program to build their most ambitious project yet, Co-op City.

Signed into law in 1955, Mitchell-Lama was passed to provide housing for middle-income working families who earned too much money to qualify for public housing but could not afford to pay market prices.

Today, because of Mitchell-Lama, someone who meets the income requirements can purchase a basic one-bedroom in Co-op City for as little as $16,500.

Taking advantage of funds made available through the new program, the UHF got to work on the swampland, bringing in five million cubic yards of sand from Gravesend Bay by boat and then pumping it through a 3-mile-long pipe, eventually raising the ground by 14 feet.

Construction was finished in 1973, and then, in 1975, Co-op City defaulted on its loan. The project had been poorly managed and shoddily constructed and now had a mortgage one and a half times the size of what was anticipated. Carrying charges, the monthly maintenance fees all cooperators had to pay, were set to go up by 25 percent, and the 50,000 residents refused to pay, setting off a 13-month strike, the longest in US History.

Finally, a compromise was reached, and on July 26th, 1976, a rented yellow Ryder truck, filled with 101,933 checks worth more than $20 million, pulled up to the Bronx County Courthouse. After a human chain of residents passed along the boxes of back-dated checks, contempt‐of‐court charges against the strike leaders were dropped, and the UHF no longer controlled the board. Now the residents were in charge; as shareholders in the co-op, they would elect their own board to run things.

Within six months, with the same issues of sinking infrastructure and rising maintenance fees plaguing the development, the new board passed an increase in carrying charges.

There has been a ton written on the strike with much more cogent analysis than I can pull off, so if you’re interested, this article by Annemarie Sammartino who wrote a book on the subject, is a great place to start.

MACHINES FOR LIVING

Architect Herman Jessor, who worked closely with Kazan on his cooperative housing projects, designed the 300 acres of Co-op City to have abundant green space, taking a page from Le Corbusier’s Towers in the Park morphology.

The design, which can best be appreciated from above, consists of ten large angled buildings called Chevrons that work like fortress walls, screening off the thruway, ten Triple-cores (+++) designed to provide the maximum amount of sunlight and ventilation and five three-tower groupings. Closer to the earth, Jessor also built 236 townhouses.

While it may not be much to look out from the outside, once you’re on the ground, it’s actually quite nice. With only 20% of the site’s 320 acres developed, there is a lot of open space though the few times I’ve visited, there have been very few people taking advantage of it. Paths lined with benches weave through the buildings, wrapping past rock outcroppings and around stands of poplar and Japanese black pines. There are baseball and football fields, tennis courts, and a community garden. Considering its location, however, there is almost no way to access the water

.

CRIME WAVE

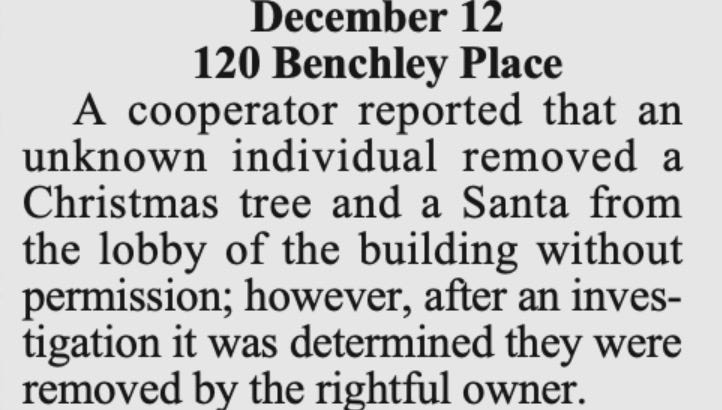

Compared to the rest of New York City, crime rates between cooperators are low, unsurprising given the outsized senior population.

These are some of my favorite incidents from a quick perusal of the police blotter in the Co-op City Times.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

For this week’s field recording, I lingered around Co-op City’s cogeneration plant while some kids talked about potato chips (1:34) before heading over to Pelham Bridge.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

This week’s featured photograph is by the great Diane Arbus, a famous portrait of Eddie Carmel in his parents in their Co-op City apartment. Arbus met Eddie when he was a performer in Hubert’s Dime Museum and Flea Circus in Times Square. In addition to appearing in circus side shows, Eddie worked as a mutual fund salesman, a stand-up comedian and performed in the band Frankenstein and the Brain Surgeons.

An article in the NY Times about Arbus and Eddie The Woman and the Giant (No Fable) - gift link

NOTES

Famous former residents of Co-op City include Kurtis Blow, Sonia Sotomayor, Richard Price and David Berkowitz, aka "Son of Sam"

For the definitive book on Freedomland, check out Freedomland USA

Some of the above pictures may seem like they are from a different neighborhood, but they are from four blocks of houses along Givans Creek that refused to move when the surrounding area was developed.

https://www.nytimes.com/1971/10/26/archives/coop-citys-grounds-after-3-years-a-success.html

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/06/26/utopia-the-bronx

The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky. Sun, May 3, 1970, Page 105

nice overview. The Freedom Land website is great. As kids, we loved seeing the buckets from the gondola ride traversing the park in the distance in lovely pastel shades of aqua and I forget what else.

For them, the robbery where they used boats to escape, according to some stories. It happened in the first year of operations.

https://images.app.goo.gl/xtwc1ArYJbht9cTW7 one of my favorite maps of all time.

Loving these. I’m often captivated by your images. What camera are you using?