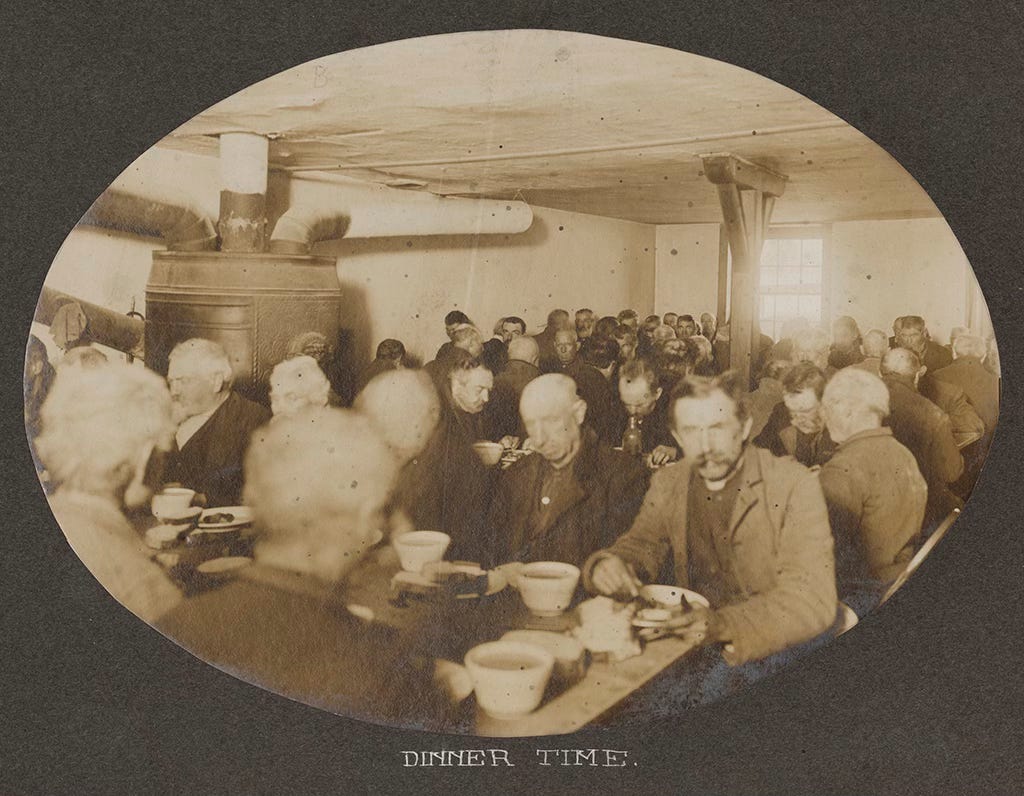

Knowing that this week's newsletter was coming out on Halloween, I thought I should probably make an effort to visit someplace sufficiently "spooky." The New York City Farm Colony, an abandoned assemblage of derelict buildings in the middle of Staten Island, a favorite destination for urbex aficionados, graffiti artists, and paintball enthusiasts, seemed like it would fit the bill. This was before I learned that Cropsey, Staten Island's real-life boogeyman, is said to have brought children to these very woods to sacrifice them in Satanic black masses. To be honest, even without this information, I found wandering around the abandoned buildings in the middle of the woods sufficiently creepy.

I learned that Willowbrook, the sleepy residential neighborhood that abuts the former Farm Colony, has a rich and somewhat disturbing history.

This small mid-island community was once home to shadow governments, tuberculosis treatment laboratories, and a center for developmentally disabled children whose deplorable conditions got the attention of both RFK and Geraldo. Not to mention the whole boogeyman thing.

Today, the neighborhood, which is just south of the expressway and borders the Staten Island Greenbelt, is the center of Staten Island’s Orthodox Jewish community.

The spookiest thing I saw was the preponderance of Make America Great Again memorabilia.

COMMITTEE FOR SAFETY

The name Willowbrook first appeared in colonial records in 1683.1 By the 18th century, a gun factory, a sawmill, and a comb factory had gone up, taking advantage of the various sources of water to power their mills.

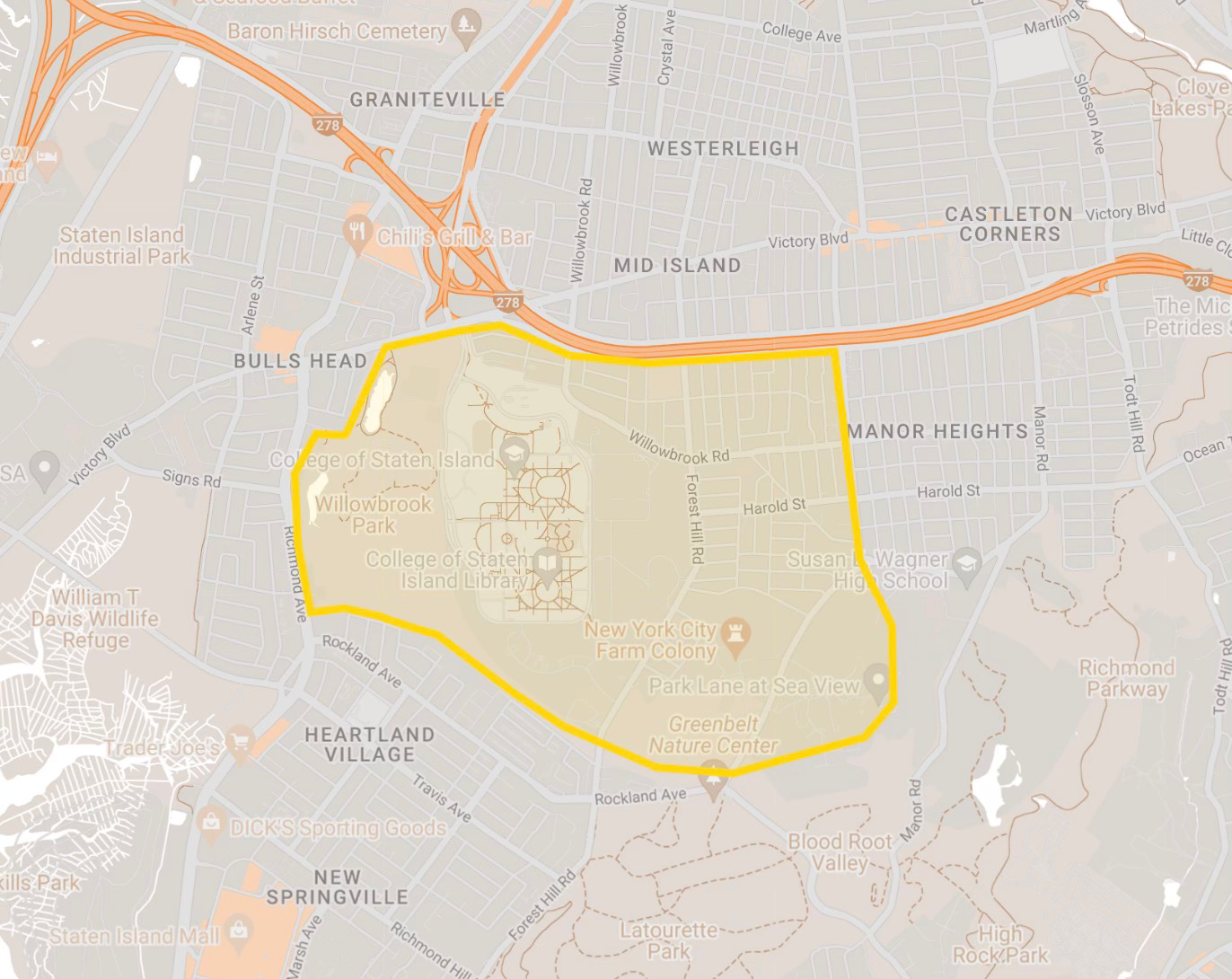

A few homes were scattered around the area, including the Christopher House, built in 1756. During the Revolutionary War, the house was used as a meeting place by the local Committee for Safety. These committees were networks of leading citizens who established a shadow government, managed military preparations, suppressed loyalists, and oversaw civil and criminal justice. The house was located on the edge of the "Great Swamp," which provided a quick escape in case the meetings were discovered.

In the 1970s, the entire structure was disassembled and relocated to Historic Richmond Town, where it was reconstructed in 1974.

I found this postcard of the house made by Staten Island shutterbug Percy Loomis Sperr on eBay.

The image caught my eye because it reminded me of a picture I had taken a couple of years ago of a similarly gnarled tree in front of a different Staten Island home.

The back of the postcard features a pitch for Sperr’s Lumitone View Cards, designed for “your discriminating friends” and printed with an "attractive and tasty effect,” a descriptor I will soon be co-opting for my own prints.

NEW YORK FARM COLONY

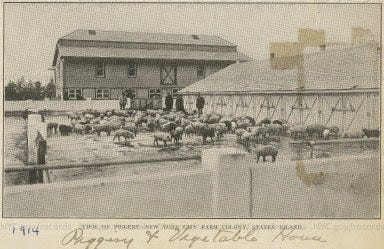

By the early 19th century, much of the Western world viewed poverty as a sign of moral weakness, prompting the rise of institutional approaches to various societal ills. These institutions aimed to “correct human failure in its various manifestations: the indigent, the mentally ill, the impoverished aged and infirm, the alcoholic, the vagrant, and the petty criminal.”2

The Richmond County Poor Farm was established in 1830 to house Staten Island's indigent population. In the following years, a cholera hospital and a house for the insane were added to the poorhouse. Residents were expected to work on the farm to earn their room and board, a cost-saving measure that was also seen as a deterrent to long-term occupancy.

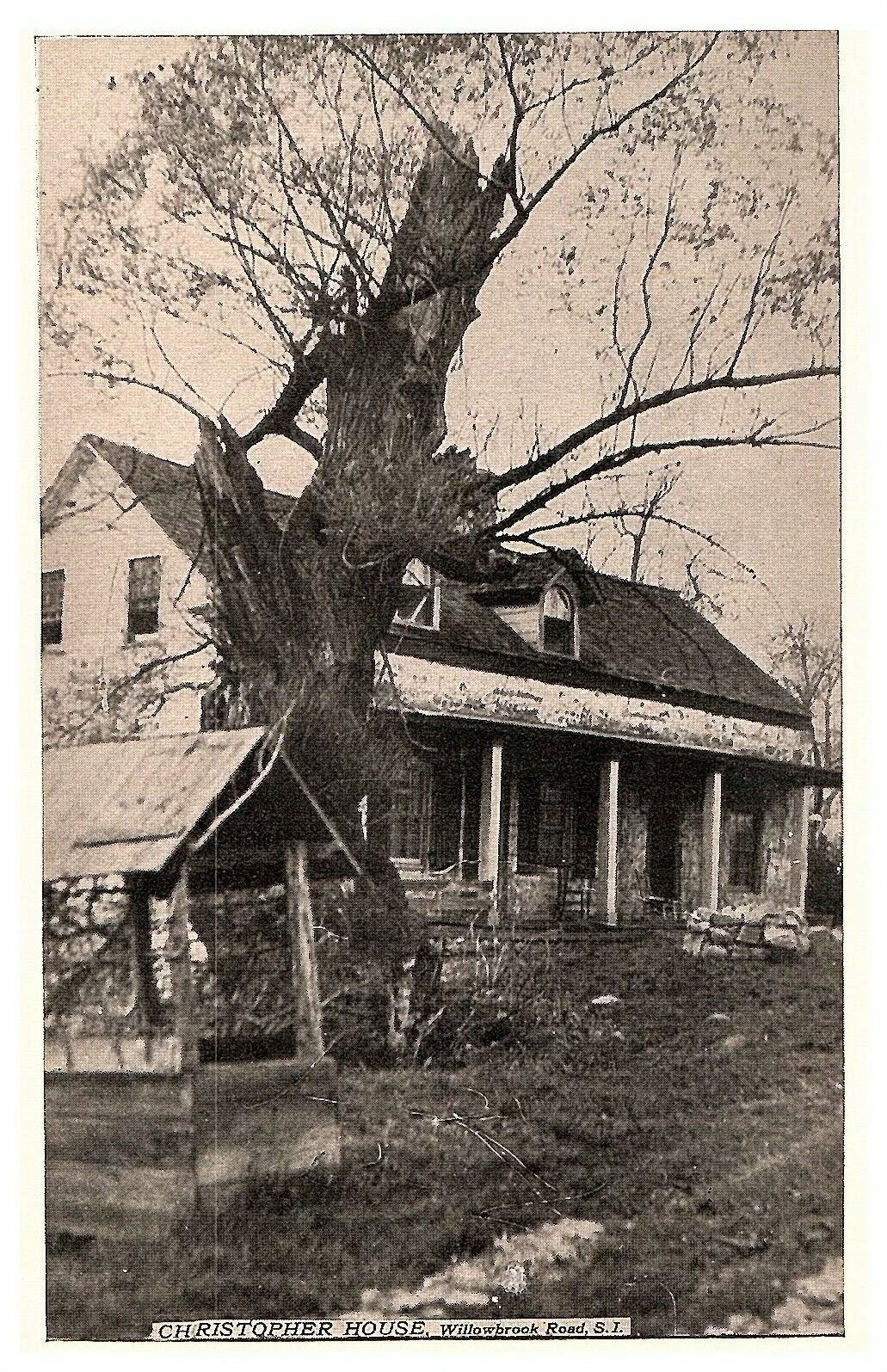

When Staten Island was incorporated into NYC in 1898, the poorhouse was put under the auspices of the recently created Department of Public Charities, the precursor to today's Department of Social Services. The department managed the city’s institutions, including almshouses, workhouses, hospitals, orphanages, and asylums, that provided assistance to people unable to support themselves. They renamed the Staten Island complex the New York City Farm Colony and designated it for the "able-bodied indigent" population.

While the inmates at other institutions under the Department of Public Charities look around and have nothing whatever to do, here they pay for their board twofold by their labor, working on the farm raising vegetables not only for themselves but for other unfortunates. No healthier spot within miles of Greater New York can be found. Situated on the western slope of Todt Hill, the highest land in Greater New York at 368 feet above sea level, it is a beautiful site with fertile fields where any kind of vegetable thrives—all it needs is cultivation.3

In addition to farming, residents were tasked with cleaning and keeping up the grounds. Inmates were put to work as carpenters, cobblers, tinsmiths, broom makers, map makers, printers, and tailors.

In 1912, with 63 acres devoted to agriculture, the 824 residents produced nearly $23,000 worth of fruit, vegetables, pork, and dairy. Anything they didn’t eat was sold or sent to other institutions under the purview of the Department of Public Charities.

As you can probably see in the above photos, the “able-bodied” individuals of the Farm Colony were becoming decidedly less so; the 1912 census indicated that over half of the institution's population was over 50 years old. Eventually, the work requirement was dropped as the Farm Colony began to provide housing to a strictly geriatric clientele.

In 1950, after selling the home she had grown up in and most of her possessions, 84-year-old Alice Austen took a pauper’s oath and moved into the Farm Colony. Austen, who you may remember from Rosebank, spent a year there before her photographs were discovered in the basement of the Staten Island Historical Society. This discovery offered her a modicum of success, allowing her to live out her last years in a private home.

With the advent of Social Security and welfare in the 1950s, institutions like the Farm Colony became obsolete. In 1975, the Colony closed for good. In the years since, its crumbling structures have gradually succumbed to the surrounding forest.

BLACK ANGELS VS WHITE PLAGUE

When it opened in 1913, Sea View Hospital, located just across the street from the Farm Colony, was the “largest and finest hospital ever built for the care and treatment of those who suffer from tuberculosis."

At the time, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death among New Yorkers, killing more than 10,000 residents in 1912 alone.

The hospital was built to isolate and provide care for the thousands of TB sufferers who couldn't otherwise afford it. The only known treatments were rest, sunlight, and fresh air.

Sprawling over 300 acres, the $4 million complex featured eight open-air patients' pavilions designed with ample balconies and large windows to maximize fresh air and sunlight for its nearly 2000 patients.

While the nurses at Sea View were not thrilled with the long shifts and the five-hour round-trip commute from Manhattan, the very real possibility of dying from the highly contagious and often fatal disease was likely seen as the job’s biggest drawback. This description of the hospital by Maria Smilios, author of "The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis," is particularly evocative.

Almost a thousand patients lay in open wards, languishing as millions of microbes gnawed at their tissues, organs and bones. All day, patients struggled to breathe, as long-lasting coughing fits often cracked their ribs, causing them to choke and gag and send swarms of live germs into the air. The bacteria settled onto bedpans, nightstands, bed frames and nurse’s carts. It floated under beds and down hallways, sneaking into every corner of the ward.

In 1929, the majority of the nurses left the hospital. The prospect of a hospital shutdown, which would send over 1,000 infected patients back into the city and tenements where the disease spread so readily, forced city agencies to devise a new plan.

To address the shortage, Sea View recruited Black nurses from the South to come to New York by offering them training at Harlem Hospital, a living wage, free housing, and, most importantly, an alternative to the oppressive policies of Jim Crow. By 1930, virtually all of Sea View's 300 nurses were Black. Of course, their new situation was no picnic either.

Besides working in dangerous conditions, the nurses of Sea View, known as the Black Angels, faced racism from hospital staff, administrators, and the patients they were treating. They were also paid less than white nurses in similar positions.

In the early 1950s, a drug called isoniazid was tested in clinical trials to determine its effectiveness in inhibiting tuberculosis bacteria in terminally ill patients. Sea View nurses worked tirelessly, administering the drug and monitoring patients’ responses. Within a few years, isoniazid had proven so successful that the hospital no longer had enough patients to fill its beds.

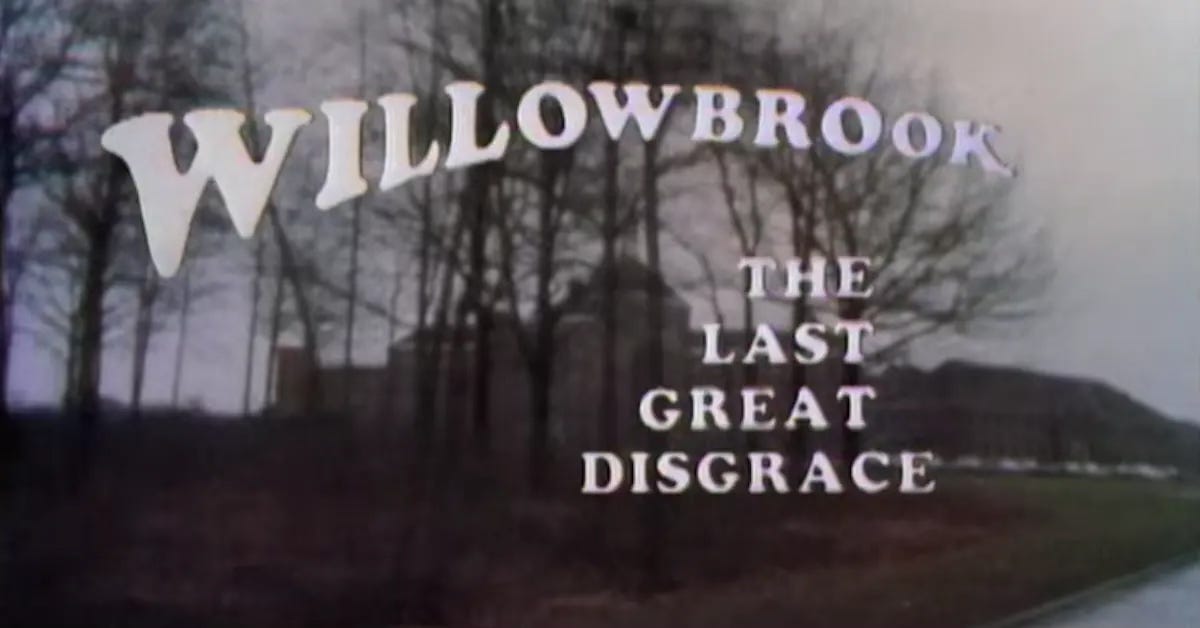

THE LAST GREAT DISGRACE

The final (and most disturbing) entry in the Willowbrook institutional trifecta was the Willowbrook State School, which opened in 1947 to provide care for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. It soon became known for its inhumane and overcrowded conditions. Built to accommodate 4,200, the facility soon had 6,000 residents, with only one attendant for every 50 kids.

After Robert Kennedy paid the institution a surprise visit in 1965, he told the press that Willowbrook was "less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo.”

It wasn’t until Geraldo Rivera’s expose, “The Last Great Disgrace,” aired in 1972, however, that people really began to take notice. A whistleblower managed to get Rivera a key to one of the wards, and the extremely disturbing footage captured by Geraldo’s team led to a class-action lawsuit against the state in 1972. The case catalyzed a national movement away from institutionalization and toward community-based care. By 1987, Willowbrook State School was closed.

CROPSEY

If you went to summer camp in New York in the 60s and 70s, there is a good chance one of your campfire stories involved Cropsey, New York’s version of the boogeyman.

The story's protagonist, Cropsey, is sometimes a judge, sometimes a camp security guard, and usually a well-liked and respected member of society. At some point, one of his children or his whole family dies in some sort of accident (a camper-caused fire, a ricocheting bullet from the riflery range, etc.) that triggers a mental breakdown. Cropsey then goes on a killing spree, strangling, stabbing, and chopping up the children of the camp or the town to get his revenge. He is never caught.

Over time, the legend mutated, and its details became more and more sinister. Cropsey has a hook for a hand; Cropsey is an escaped inmate from an asylum, a deranged psychopath kidnapping children and dragging them into the woods to murder them.

In Staten Island, the story sometimes involved an escaped inmate who lived in the abandoned buildings of the Farm Colony or the tunnels underneath Willowbrook State School.

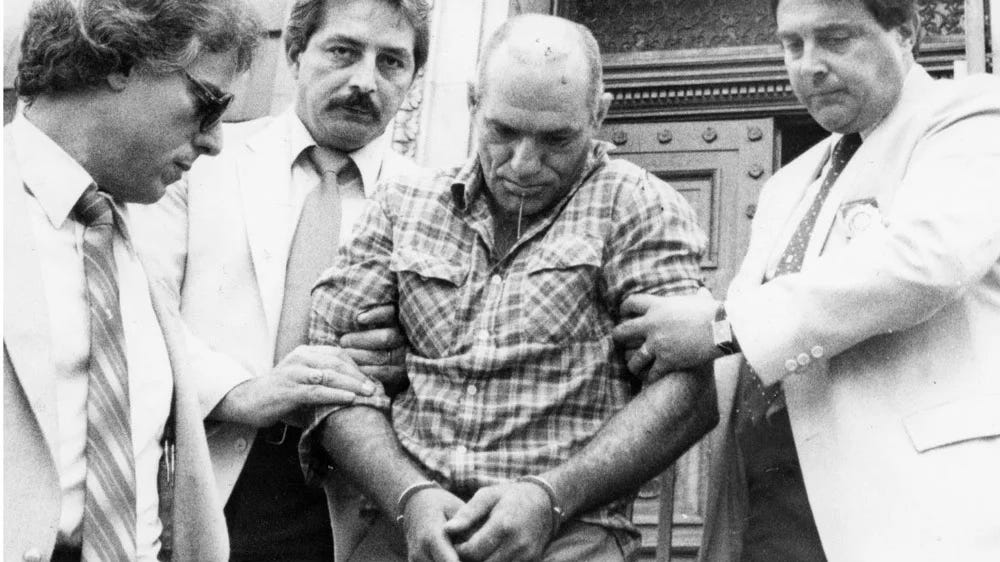

When Andre Rand, a former custodial worker at Willowbrook, was arrested in 1987 for the suspected kidnapping and murder of Jennifer Schweiger, a 12-year-old girl with Down syndrome, the urban legend became a reality.

Rand had been living in the woods in Willowbrook Park adjacent to the school, and Jennifer’s body was found in a shallow grave near his campsite. He quickly became a suspect in several other cold case murders involving other Staten Island children as well as two employees of the Willowbrook State School.

While there was never any physical evidence tying him to the murder, this image of a drooling Rand in cuffs being escorted out of the police station pretty much sealed the deal in the court of public opinion.

Ultimately, the jury could not reach a verdict on the murder charge, but Rand was convicted of first-degree kidnapping and sentenced to twenty-five years to life in prison. In 2004, Rand was again brought to trial, this time charged with the kidnapping of Holly Ann Hughes, a crime for which he was also found guilty.

Not everyone was convinced Rand was responsible. A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the “Seer of Bayside," Veronica Lueken, who gained a cult following because of her visions of the Virgin Mary. Shortly after Rand was arrested, Lueken took it upon herself to weigh in on the case. She penned a letter to Jennifer Schweiger’s family stating that Rand didn’t kill Jennifer but was instead working as an errand boy for the Satanic Church of the Process. I’m sure hearing that was a relief.

Did a little checking on the recent disappearances and murders of these kids, and it looks like some of them were victims of what is called the Satanic Black Mass. Andre Rand did not kill Jennifer; all he did was bring her to the coven. Too bad they covered it up, but who wants to admit that Staten Island is literally going to hell? It’s a picnic ground for them, with bodies buried that will never be found.

I learned about Lueken’s letter from the 2009 documentary Cropsey, which goes into great detail on Andre Rand, the tunnels under Willowbrook, and the satanic rituals in the Farm Colony. There are interviews with cops, supposed witnesses, and a bevy of Staten Island characters.

If you’re not trick or treating tonight, watching the film (free on YouTube) may be a good way to spend your evening.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio is a short one. Just a few moments of ambiance in the middle of the woods, followed by some leaf crunching and geese heading south.

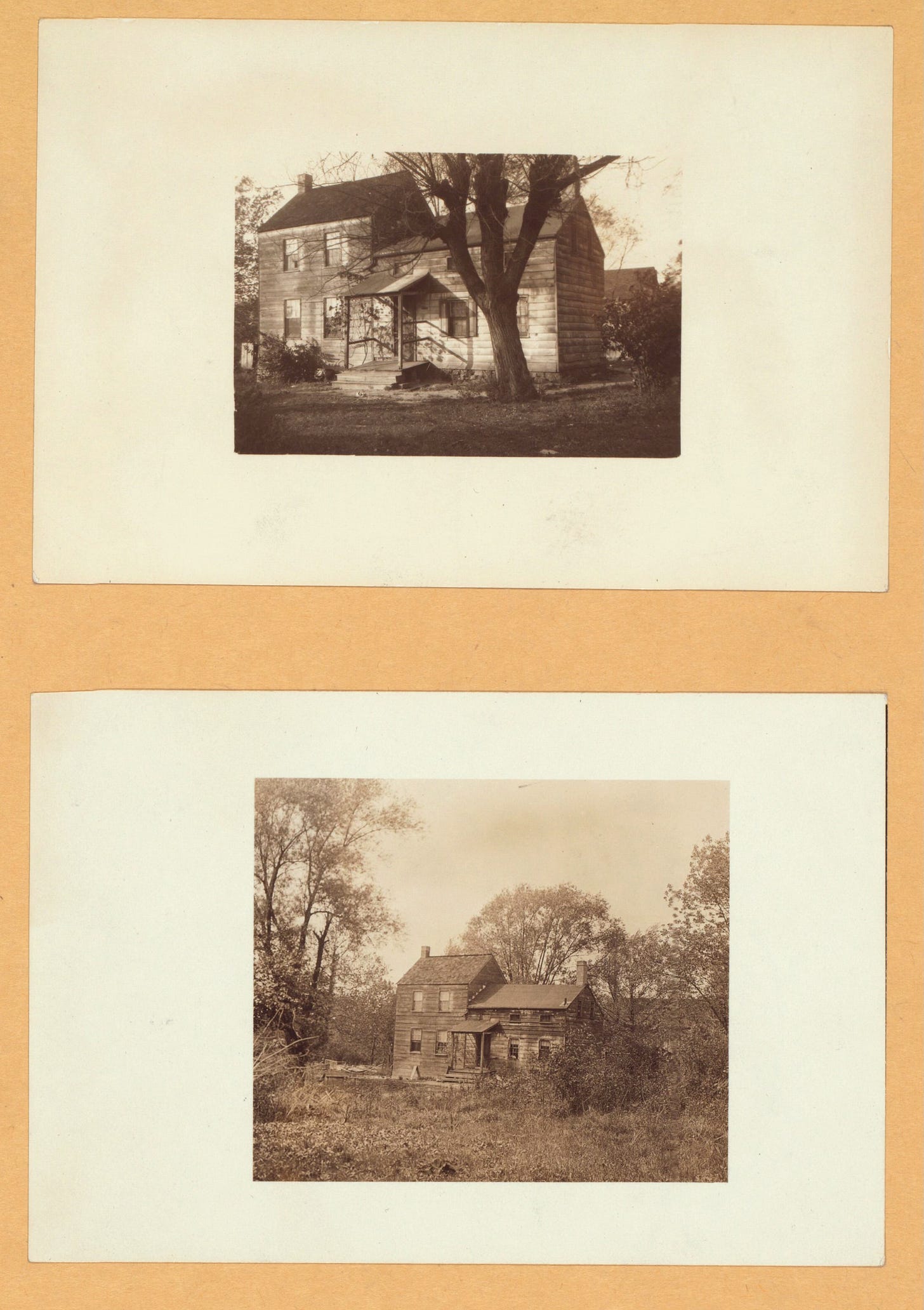

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

I love these two pictures of a house on Hall Avenue and Willowbrook Road taken for the NYPL by Percy Loomis Sperr. 1922 and 1926.

ODDS AND END

Between stick-ups, famed bank robber and prison escape artist Willie Sutton, a perennial entry on the F.B.I.'s Most Wanted List, used to work as a porter at the New York Farm Colony in the 1940s. Known as the Babe Ruth of Bank Robbers, Sutton is often (wrongly) attributed with the quote, “Why do you rob banks? Because that's where the money is.”

Cropsey makes an appearance in the 1981 slasher flick The Burning. So does Jason Alexander with a gloriously full head of hair.

Taking Care: The Black Angels of Sea View Hospital is an exhibition currently on display at the Staten Island Museum until December.

If you want an antidote to the MAGA signage of Willowbrook, check out the latest newsletter from

. #nauseouslyoptimisticSpeaking of Veronica Lueken, on my drive back from Willowbrook, I was amazed to see a giant TLDM (the group committed to promoting Leuken’s messages and directives) billboard on the side of the BQE. I wasn’t able to get a picture, but this similar billboard in Albany gives you the idea.

https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/willowbrook-park/history#:~:text=The%20original%20105.41%20acres%20of,Fund%20on%20November%2020%2C%201929.

https://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1408.pdf

Annual Report of the Department of Public Charities of the City of New York; 1902 (New York: Mail and Express, 1903), p. 37.

Thank you! Your photos are great and your research is thorough. I love learning about the borough I live in. 😃

Spooky! It's so hard to believe the incomprehensible horror of care centers for the disabled even just a few decades ago.