The most recent census found seven of the ten neighborhoods in New York City with the greatest percentage of people claiming Italian ancestry are on Staten Island. While the vast majority of the borough’s Italian-American population arrived after the opening of the Verazzanno Bridge in 1964, Rosebank, the small neighborhood sitting nearly at the entrance to New York Harbor, was once the Staten Island spot for Italian ex-pats.

Legend has it that the waterfront neighborhood bordered by I-278, the Staten Island Railway tracks, and Fort Wadsworth to the south got its name from the banks of roses that once lined its streets.

Garibaldi

Italian inventor Antonio Meucci and his wife Esterre began renting a home in the area in 1850. The Meucci’s were soon joined by Italian hero Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had fled to the US to escape political persecution.

In 1836, faced with a death sentence for his participation in an uprising in his home country, Garibaldi did what any good revolutionary would do and traveled to South America. There, he joined the rebels in Brazil’s Ragamuffin War, mastering the art of guerrilla warfare. He later formed and led the Italian Legion, a group composed mainly of Italian immigrants who fought for Uruguayan independence. He then traveled back to Italy but had to flee again after a failed defense of the Roman Republic.

That’s when Garibaldi found his way to Staten Island. He worked alongside his fellow countryman Antonio Meucci, who had built a paraffin candle factory, the first of its kind in the world. The two bearded Italian candlemakers also opened a brewery, cementing their legacies in the hipster pantheon.

The only hero the world has ever needed is called Giuseppe Garibaldi

-Che Guevara

In 1854, Garibaldi returned to Italy and led the Expedition of the Thousand, which succeeded in conquering the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, a significant step toward Italy's unification.

Meucci, on the other hand, stayed put in Staten Island, where he continued running the candle factory and brewery. In his free time, he dabbled in electroshock therapy and developed a chemical process for preserving corpses during long sea voyages.

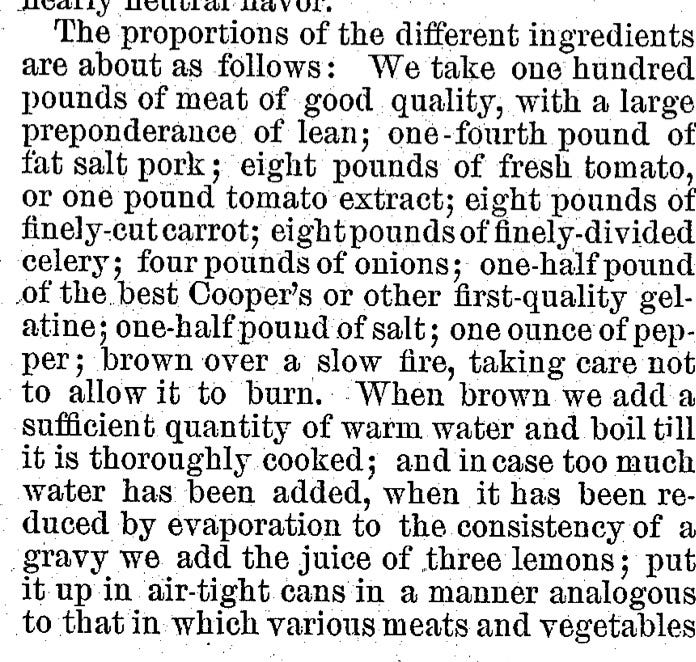

He also amassed a formidable stack of patents, including one for a "Lactometer" that could chemically detect adulterations of milk and another for "Effervescent Drinks." Meucci held a patent for a “plastic paste for billiard balls and vases” and designed the modern coffee filter. He also pioneered paper recycling technology, created a smokeless kerosene lamp, and even secured a patent for “Sauce for Food.”

Somehow, Meucci had managed to patent Bolognese.

Unfortunately, Meucci’s most important invention was the one for which he failed to get a patent.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL WAS ITALIAN?

Look up who invented the telephone in any school textbook, and invariably, you will find a picture of Alexander Graham Bell. Well, that is unless the textbook is in Italian. Then there is a good chance you will find the story of Antonio Meucci. Any Italian elementary student will tell you that the transplanted Florentine had devised a way to transmit voices over a wire some 16 years before Bell.

Meucci’s aforementioned electroshock therapy treatments involved attaching two lengths of copper wire to an array of batteries. The patient would hold one wire in their hand and put the other under their tongue while the current would slowly increase, ostensibly reversing whatever affliction they suffered.

One day, Meucci was treating a man suffering from a migraine, and once the batteries were switched on, like any sane person who had an electrified copper wire stuck in their mouth, the patient started to scream. Meucci, however, didn’t just hear the screams; he detected them running through the wires.

It’s possible that, contrary to popular opinion, the first words ever spoken over a telephone were not, "Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you,” but rather, “Aaarghhhh!”

It was then that Meucci began working on the invention he dubbed the teletrofono in earnest.

When his wife became sick with rheumatoid arthritis, Meucci installed a telephone-like device within his house so they could communicate between the second-floor bedroom and his basement lab.

On December 8th, 1871, Meucci filed patent caveat No. 3335 titled "Sound Telegraph," which described the communication of voice between two people by wire. A patent caveat is a notice of intention to file a patent application later rather than an actual patent. Caveats were cheaper and only lasted a year, but they prevented anyone from registering the same patent. After two years, Meucci let the caveat lapse.

Then, in 1876, Alexander Graham Bell submitted his patent application, and the rest is history. In other words, Antoni Meucci got robbed. Everybody knows that.

QUARANTINE

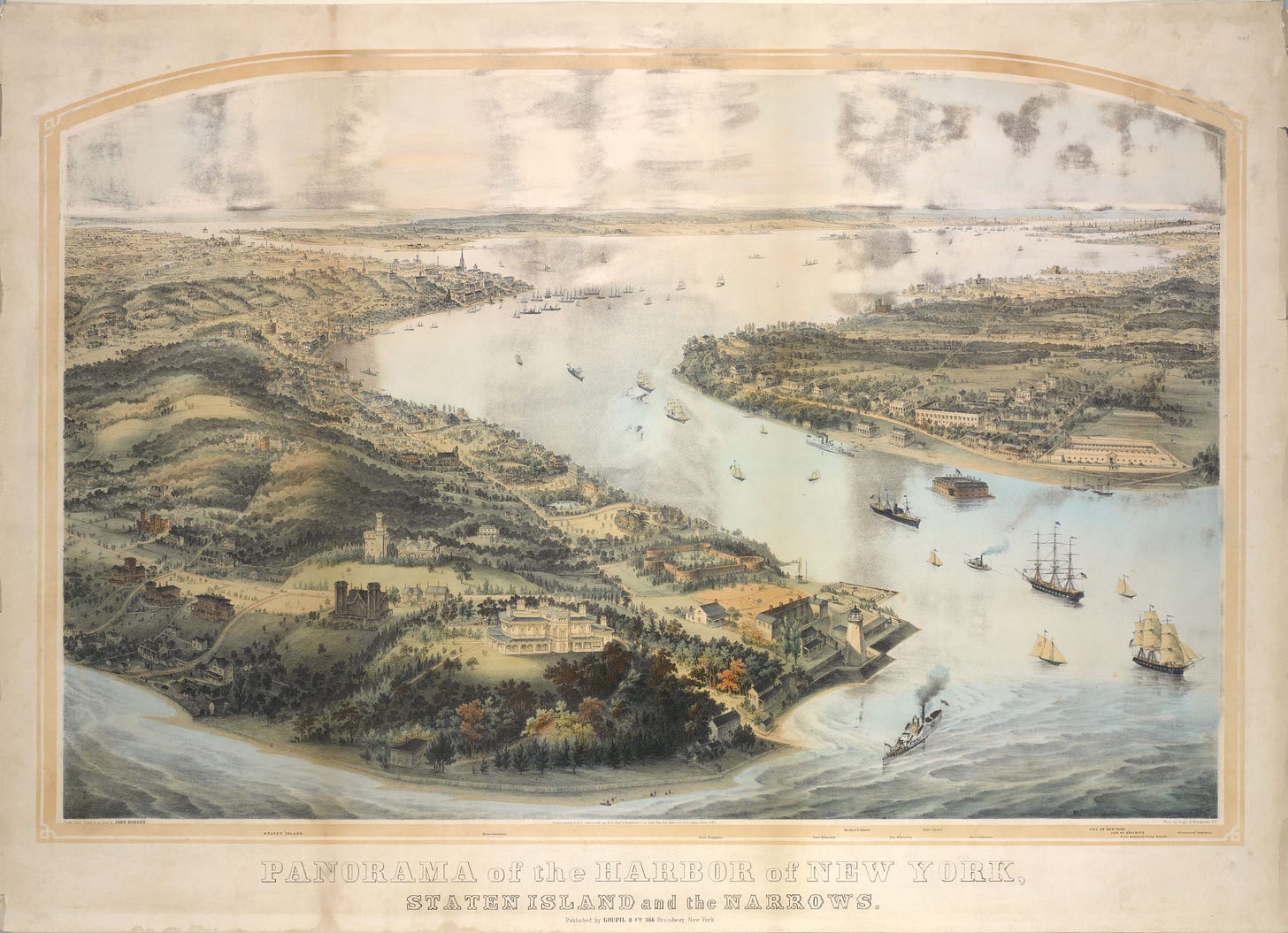

Around the same time that Meducci’s caveat lapsed, the Rosebank quarantine station opened. The building served as an administrative hub for medical officers tasked with inspecting recently arrived boats.

In a small tower, a telegraph operator received reports from Fire Island and Sandy Hook on approaching ships. As a vessel drew near, the operator poked his telescope out one of several narrow second-floor windows to confirm the ship’s name and other details.

Down below, a bell on a forked pole was tolled, summoning, from one of the houses on the hill, a blue-uniformed doctor who was to be transported by tugboat to examine the vessel’s travelers.1

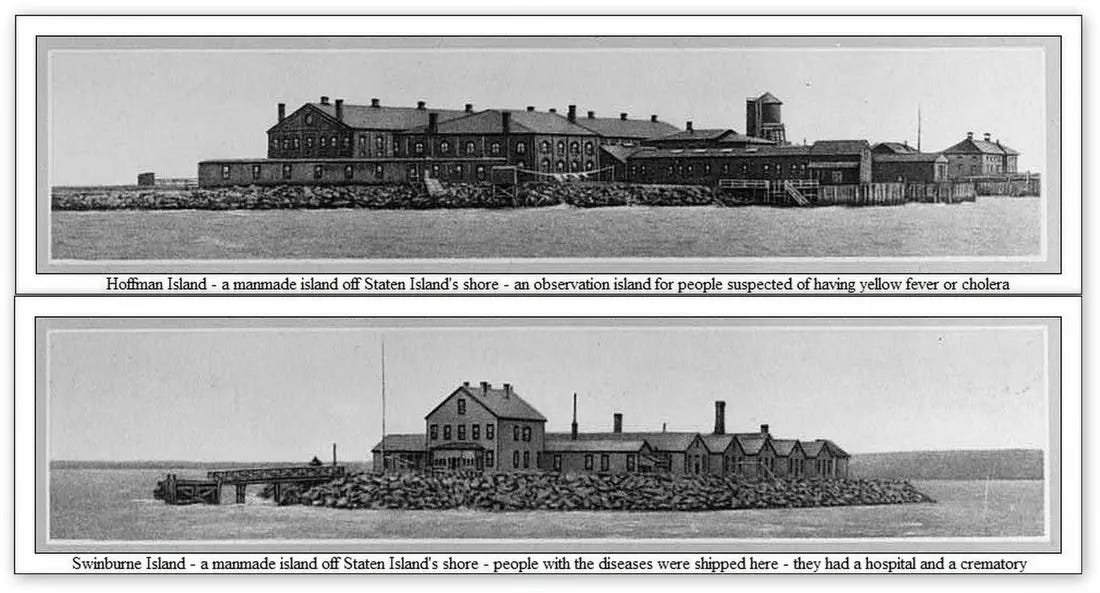

Otherwise healthy passengers on ships where inspectors found signs of disease, were sent to Hoffman Island for observation. If the passengers were noticeably sick, they were sent to the smaller Swinburne Island, equipped with a hospital and crematorium.

Both islands had been recently built from landfill after locals, not thrilled with the prospect of having a bunch of infectious disease vectors in their midst, repeatedly burned down the quarantine facility built near their homes.

You would think that a place tasked with keeping a city free from the threat of a pandemic outbreak would be pretty somber, but according to a 1911 article in the Elmira Star Gazette, these quarantine officers really knew how to let off steam.

One episode of particular interest comes from life of the party, Arthur Denise, who claimed that during a night of festivities in the second-floor library, he “emptied the ashes of the late Colonel George E. Waring, the sanitary engineer who died of yellow fever in October 1898, out of a window at quarantine and after cleaning the urn had mixed drinks in the receptacle for the party.”

The man in charge of the station was Dr. Alvah H. Doty. While he was not present for the urn incident, Doty claimed, in a clear case of missing the forest for the trees, that if any ashes were thrown out, they could not have been those of the late Colonel as those had already been sent to the family.

Despite the hijinks of his underlings, Dr. Doty was a well-respected and “eminent sanitarian” who served as the Health Officer of the Port of New York from 1895 to 1912.

CLEAR COMFORT

One of Dr. Doty’s Rosebank neighbors was Alice Austen.

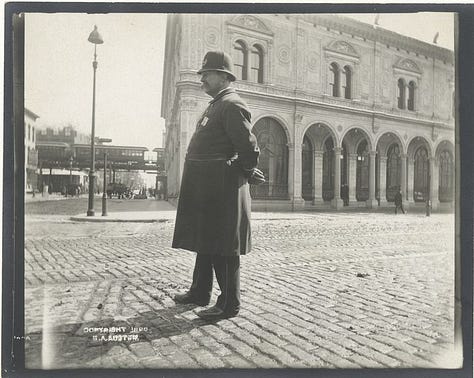

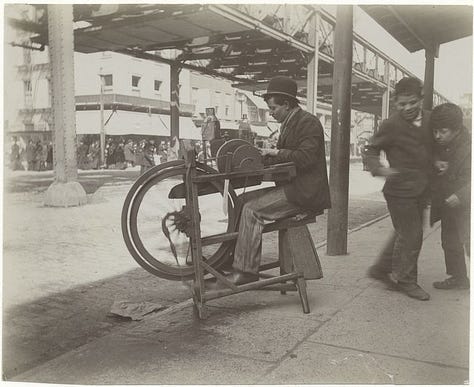

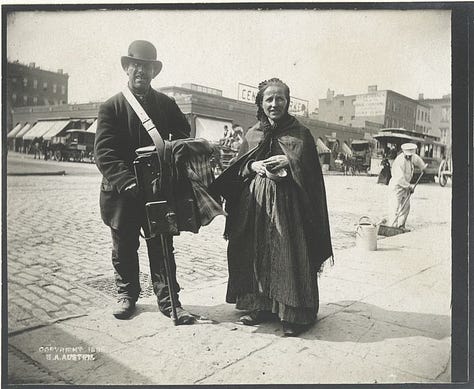

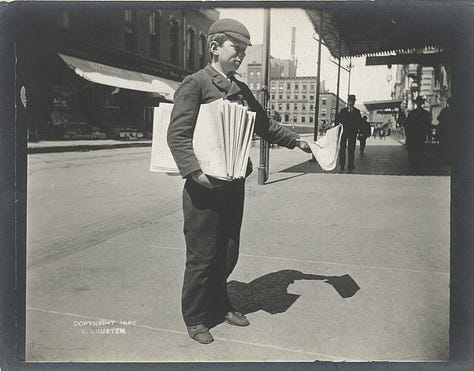

If Staten Island had a photographer wall of fame, names like John Gossage, Christine Osinski, and Percy Loomis Sperr would all occupy a prominent position. Atop them all, however, would be Rosebank’s own Alice Austen.

Frequently cited as one of the first female photographers to leave the confines of the studio, Austen was visually omnivorous. Her subject matter varied from landscapes to portraiture and even action photography.

Austen grew up with her mother and grandparents in a Victorian cottage in Rosebank they called Clear Comfort. Introduced to photography by her uncles at a young age, Austen was soon lugging large format cameras and glass plates all over the city and beyond, eventually amassing an archive of over 8,000 images.

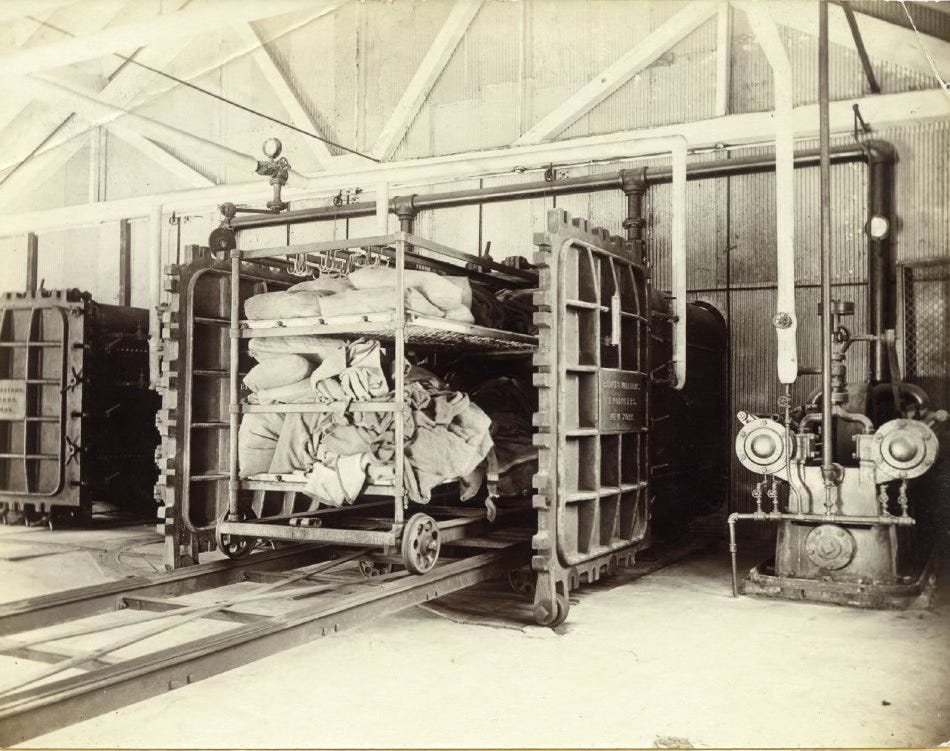

Dr. Doty commissioned Alice to document the quarantine operation which she did for more than a decade, photographing the station, the laboratories, the boats and the islands.

In 1917, Austen’s partner, Gertrude Tate, moved into Clear Comfort. Maria Popova wrote a great piece on their relationship in her newsletter, The Marginalian.

Eight years later, the stock market crashed on Black Tuesday, and Austen lost her considerable inheritance. In 1944, they were forced to sell Clear Comfort and soon after, with no money to her name, Austen had to move to the New York City Farm Colony, a poorhouse in Willowbrook, Staten Island.

She would likely have died there if not for writer and historian Oliver Jensen, who rediscovered Austen’s photographs in the basement of the Staten Island Historical Society in 1950. He had some of her photos published in Life magazine and organized a show of her work. Austen was able to make enough money from the publishing of these photos to move into a private nursing home. She died on June 9th, 1952.

Of all the Austen photos I’ve seen, I think her “Street Types of New York” project published in 1896 may be my favorite. These formal portraits of people at work in the city function both as historical documents and as art.

PINK PIGEONS

The longest operating pigment factory in North America, the G. Siegle Company Color Works factory, was built in Rosebank in 1907 and operated for 101 years before being demolished in 2008.

Rosebank residents would often catch glimpses of wildlife whose fur and feathers had been tinted by the plant’s byproducts.

“I used to see pink pigeons,” one of the men said, his eyes widening as he spoke. Residents of the neighborhood often speak with awe at having seen red-tinted birds, cats or other animals that had apparently frolicked near the powdery pigment produced at the plant.

Reading this reminded me of the story about the exotic yellow bird that was rescued on the side of the road in England in 2019.

Upon further inspection, the staff at the Tiggywinkles Wildlife Hospital determined that the bird was actually a seagull that had found its way into a pile of turmeric.

Interestingly, just three years prior, the same thing had happened when another seagull had fallen into a vat of chicken tikka masala. While the staff at the Gloucestershire animal hospital were struck by the gull’s vibrant color, it was his smell that really took them aback. “The thing that shocked us the most was the smell. He smelled amazing, he really smelled good.”

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio is a little short. Not much going on sonically in Rosebank, at least when I was recording. My favorite moment is the mozzarella shout-out at 1:10. Otherwise, it’s just birds (potentially pink) and waves.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

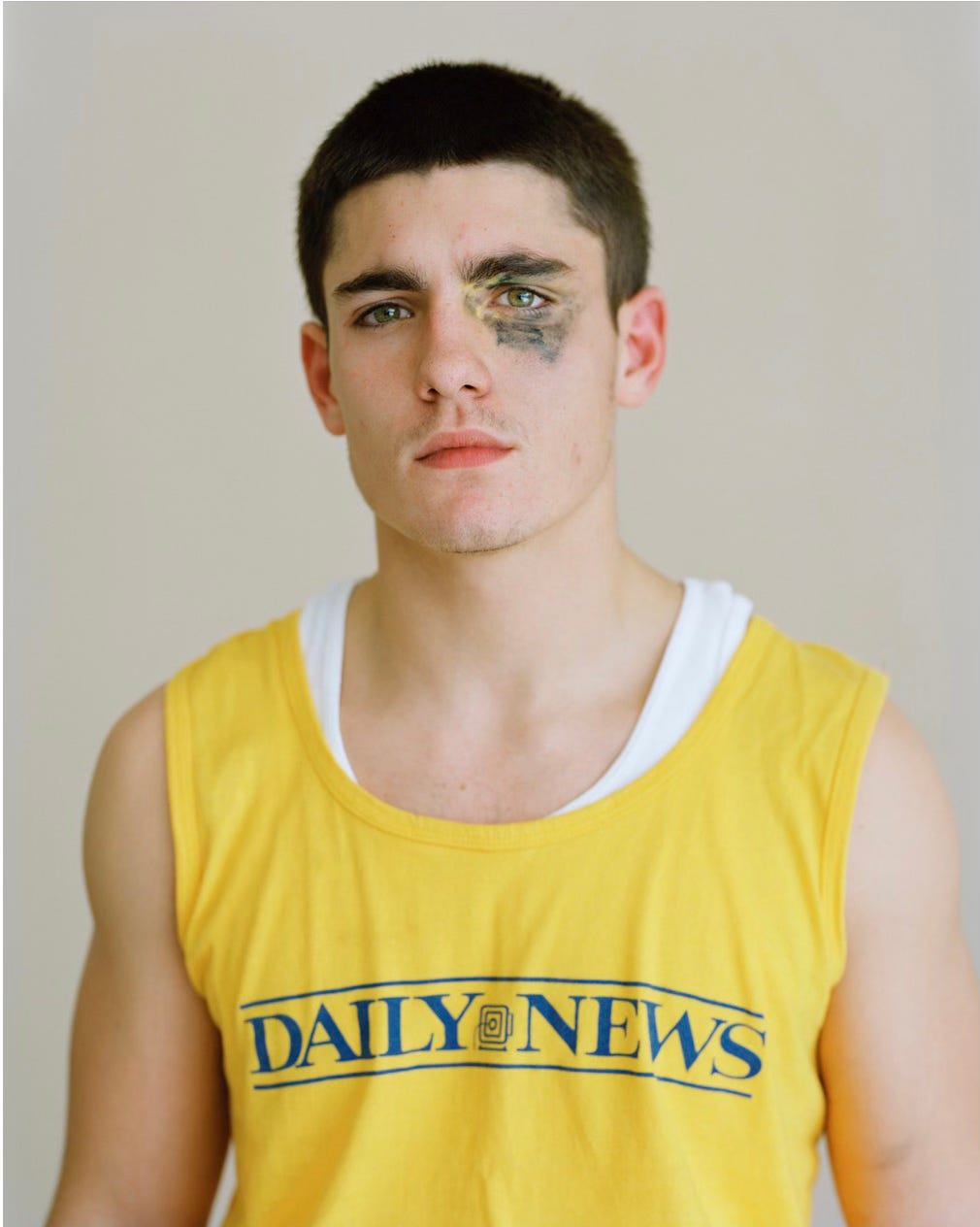

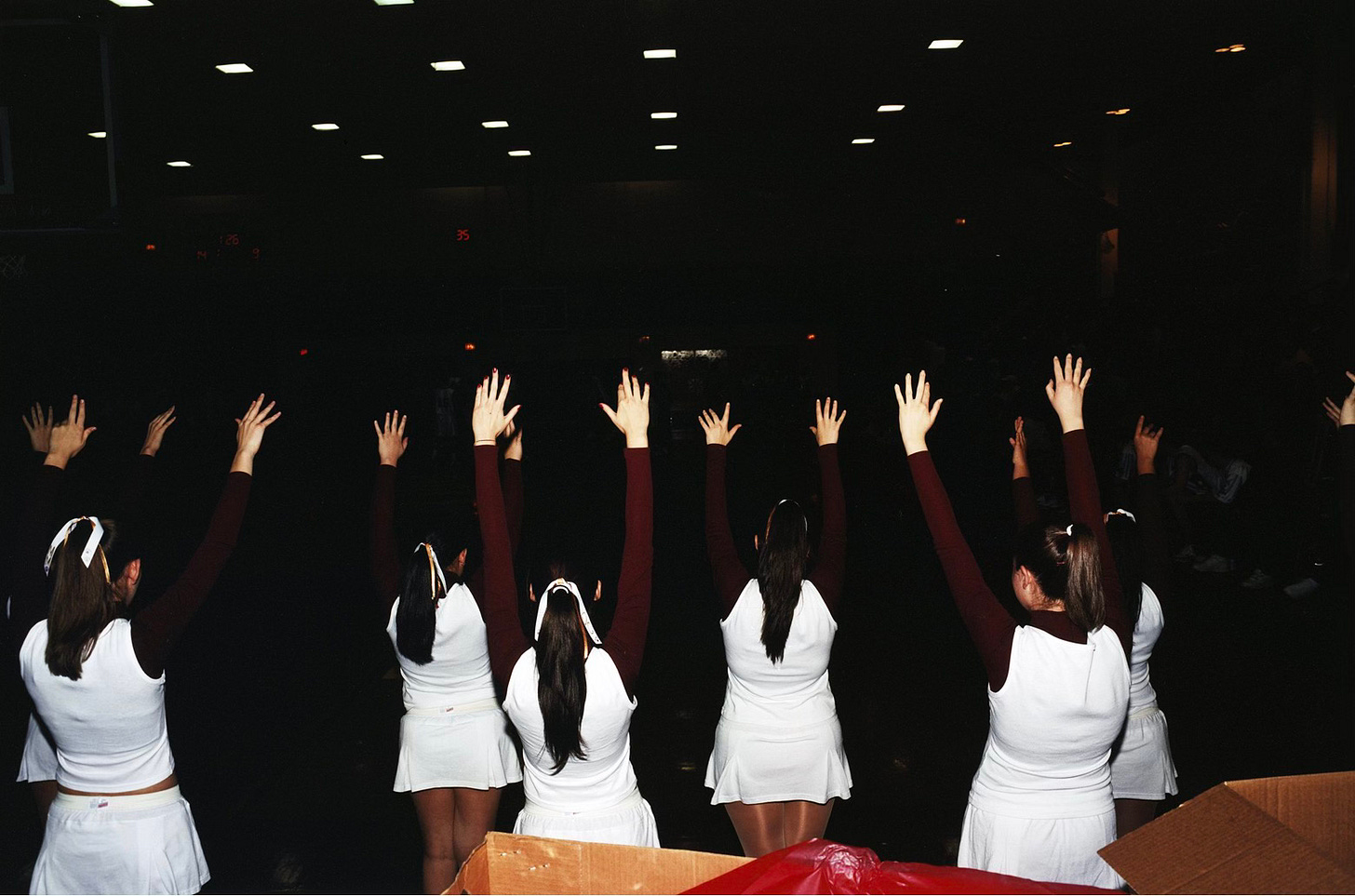

Paul Moakley is another candidate for the Staten Island Photography Hall of Fame. He has been the caretaker and curator at the Alice Austen House for over 15 years. He is also a photographer, and his projects Staten Island and Vir Fidelis (revisiting his former Catholic high school) are some of the best contemporary photos of the island I’ve seen.

Paul was also TIME magazine’s editor at large and is currently an executive producer at The New Yorker. Here is an interview in Aperture about Moakley’s work at TIME.

ODDS AND END

I have always loved the 1937 photo by Berenice Abbott of the Garibaldi-Meucci house. This architecturally bizarre and exceptionally snug addition was built over the house in 1907 and, unfortunately, taken down in the 1950s.

Bonnie Yochelson’s book Too Good to Get Married: The Life and Photographs of Miss Alice Austen is coming out next year

If you make it to Rosebank, of course you need to visit the Alice Austen House Museum. A few blocks away, you can visit the Garibaldi Meucci Museum. Then, make your way to Our Lady of Mount Carmel Grotto to complete the neighborhood trifecta.

For a bite to eat or a coffee, I like the (vegan-friendly) Bloom Cafe. Favorite dish: Bloom Burger. 5 stars.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/22/realestate/quarantine-hoffman-island-swinburne.html

I’m sorry while everything about Rosebank and the people you covered was fun, my fave characters in this issue are turmeric gull and masala gull!

Wish you had included some text with your photo of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Grotto which is an extraordinary place to visit. Even if you are not religious, it is a work of traditional art to appreciate.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel Grotto is a national historic district located at 36 Amity Street in Rosebank, Staten Island, New York. It is a historic Roman Catholic grotto designed and constructed by the local Italian American community. Work on the distinctive concrete and stone folk art structure was begun in 1937 and continues to the present. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.

It is surrounded by residential neighborhood and is a shocking vista when you get there. Every square inch is filled up.

They have a large yearly feast described as great food, music and games and even rides for the kids.

Also a procession thru the streets (I have never gone)

https://forgotten-ny.com/2008/10/staten-island-shrine/

Lots more pictures and descriptions