Longwood, located in the heart of the South Bronx, is often grouped together with Hunts Point, the peninsula just to its east. However, the construction of the Bruckner Expressway in 1973 created a clear boundary between the two neighborhoods. Besides the Bruckner, the neighborhood’s other borders are East 167th Street to the north, East 149th Street to the south, and Prospect Avenue to the west. Longwood borders the neighborhoods of Crotona and Morrisania, which once stretched from Harlem to the East River.

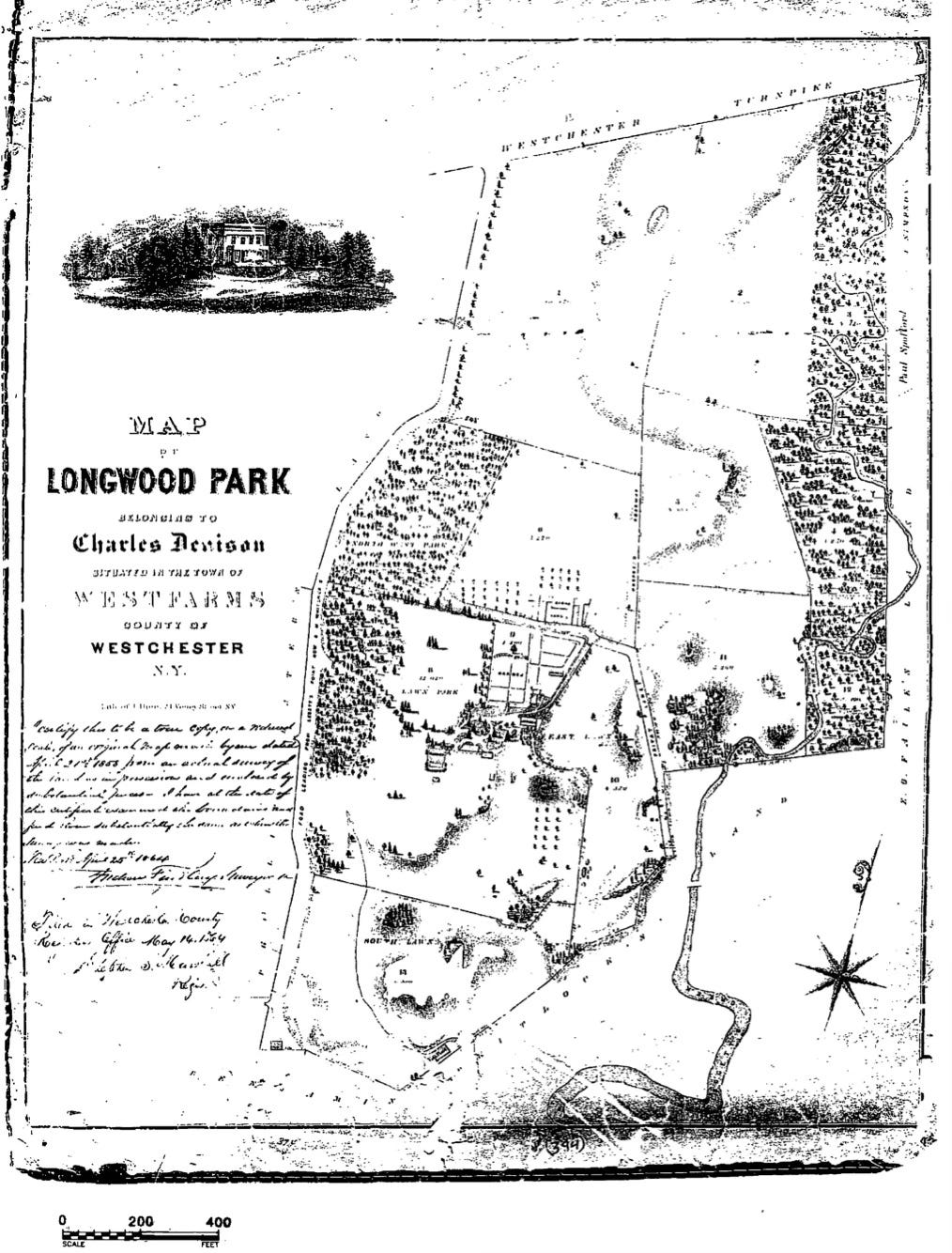

One of the major landowners in the Morrisania township was merchant Charles Denison who passed on his vast estate to his son-in-law, Samuel B. White.

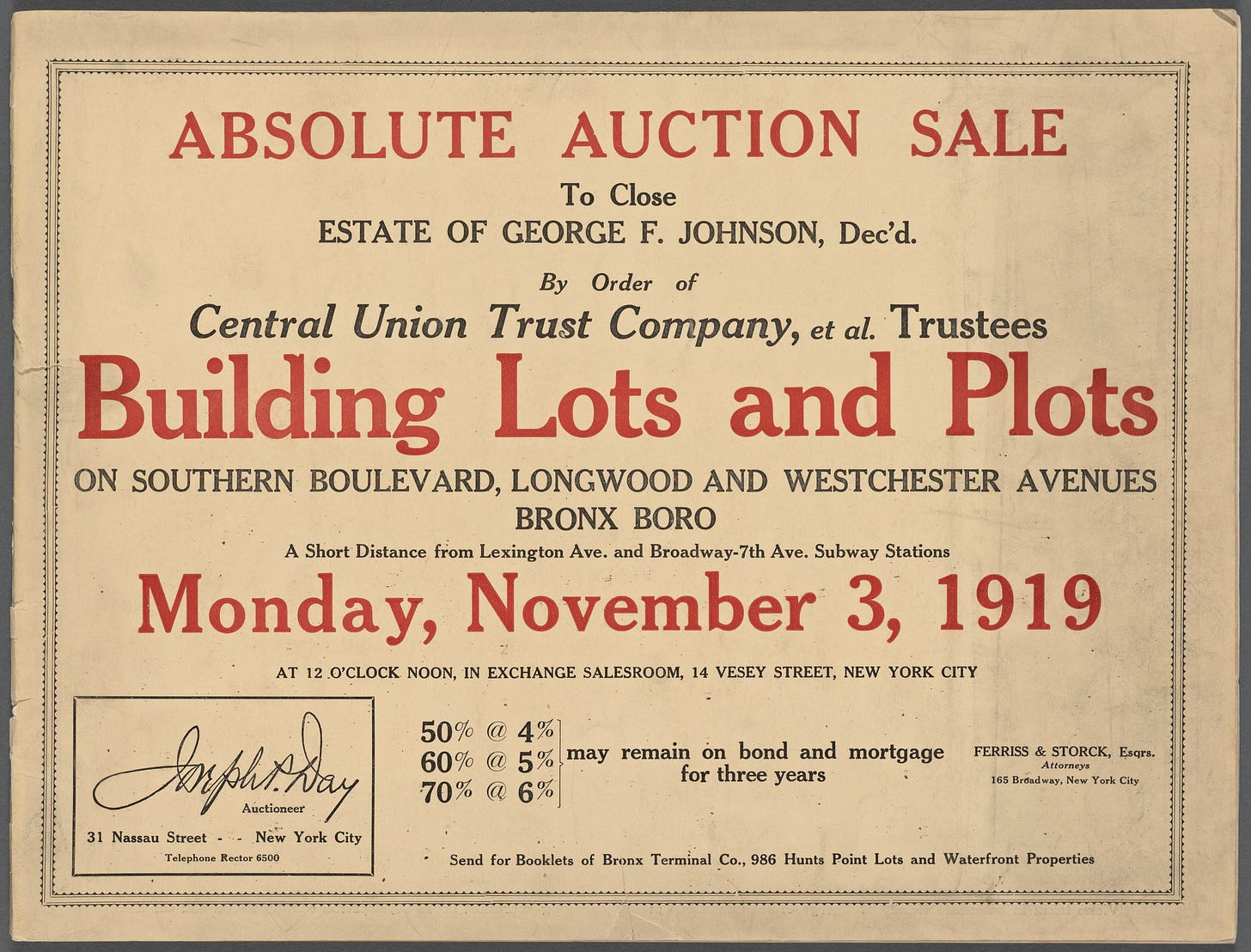

When White died, real estate developer George B. Johnson moved in and set up shop in the old White mansion.

Johnson was one of the first developers to see the potential of the new neighborhood that would soon be connected to the rest of the city. He enlisted architect Warren C. Dickerson to design several homes that are still intact today, making up the Longwood historical district, which the NY Times called “some of the best examples of turn-of-the-20th-century architecture that transformed the Bronx into an urban extension of Manhattan."1

In 1904, the IRT connecting the Bronx to Manhattan opened, and cheap rapid transit from Manhattan catalyzed a mass migration from the cramped tenements of Manhattan to the large new five-story buildings going up all over the Bronx. The neighborhood kept growing.

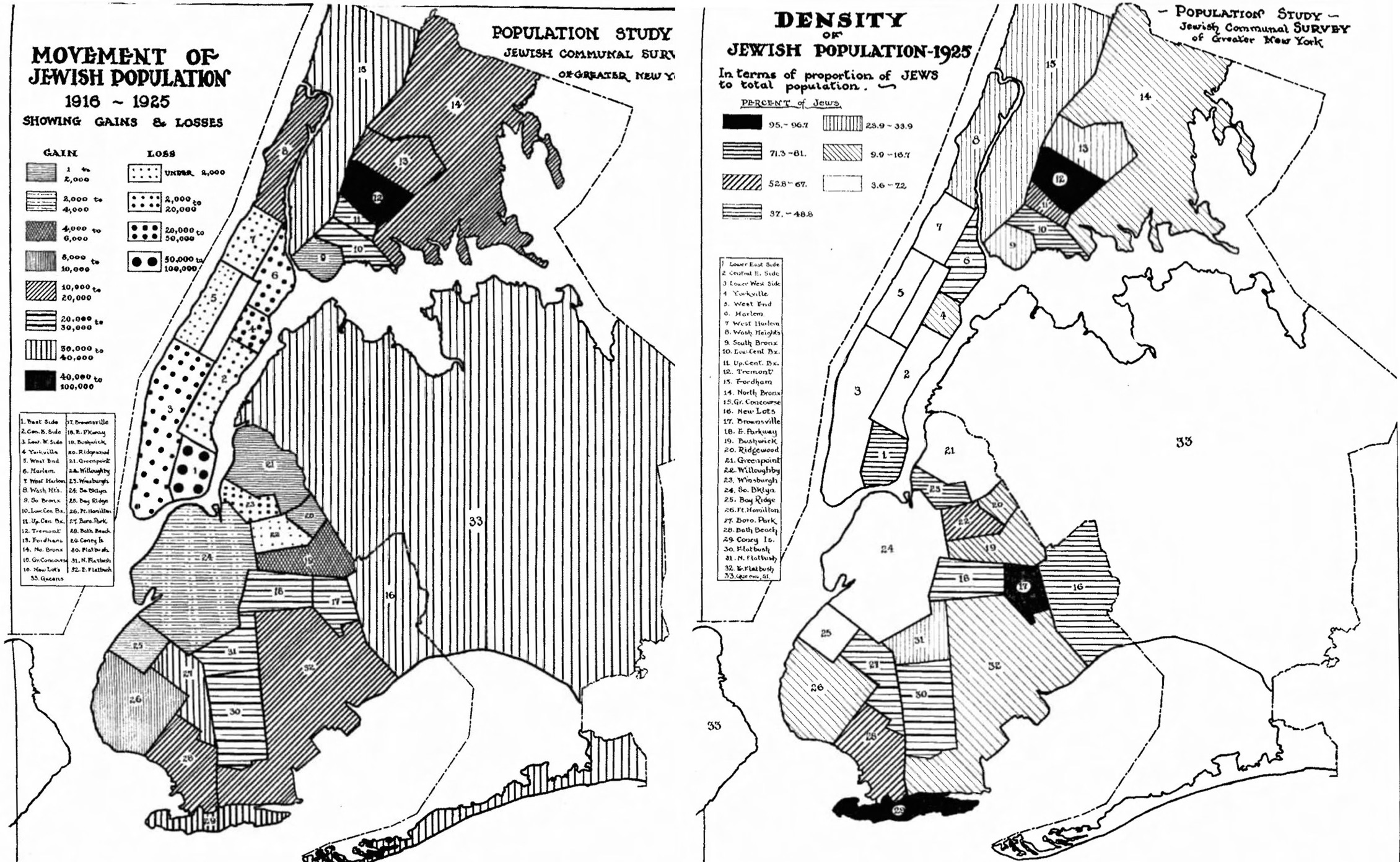

Jews from Central and Eastern Europe and their descendants were the largest bloc to make the move from Manhattan to the Bronx. These maps show the movement and density of the city’s Jewish population in 1925.

A study by the Bureau of Jewish Social Research reported that by 1925, Longwood was 71 percent Jewish.

GOD OF VENGEANCE

Several theaters, including Loew’s Spooner, the Boulevard Theatre, and Prospect Theater, opened to entertain Longwood's rapidly growing population. The Prospect, which had 1,500 seats and was one of the largest theatres in the Bronx, presented theater, vaudeville, and burlesque shows.

God of Vengeance, a Yiddish play written in 1906 by Sholem Asch, is about a Jewish brothel owner whose daughter has a lesbian relationship with one of his prostitutes.

An english version of the play premiered on Broadway at the Apollo Theater in 1923. The Society for the Suppression of Vice was not pleased and lodged several complaints. The aptly named Arthur Hornblow, a critic for Theater Magazine who apparently didn’t get out much, agreed.

“A more foul and unpleasant spectacle has never been seen in New York.”

On April 14th, less than a month after opening, the play was shut down mid-production. The producer and entire cast were indicted for violating the New York Penal Code and later convicted on charges of obscenity, the first conviction of a performer in a play for immorality by an American jury. Two days later, the play opened at the Prospect Theater, where it continued its run. In August 1934, it began operating as a Yiddish theater and, later, a movie house.

The building was restored in 2000 as a live performance venue but closed in 2006.

I learned about the theater from the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

EXODUS

In the 1940s, Puerto Rican families began to leave East Harlem and, like Jewish families 40 years earlier, moved en masse to the South Bronx. By 1960, the neighborhood was 47 percent Puerto Rican. Meanwhile, Jewish families were gradually moving north, many choosing to settle in the newly constructed Co-op City.

The exodus out of the neighborhood accelerated after the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, one of many Robert Moses projects that prioritized infrastructure over people. The expressway displaced thousands of residents from their homes and irrevocably altered the character of the South Bronx.

With a declining population came a decrease in property value. This was compounded by the redlining of much of the South Bronx. Soon, landlords were letting their buildings fall into disrepair and, in some cases, paying teenagers to burn them down so they could collect on the insurance.

A SPIRALING MATRIX OF BEEFS

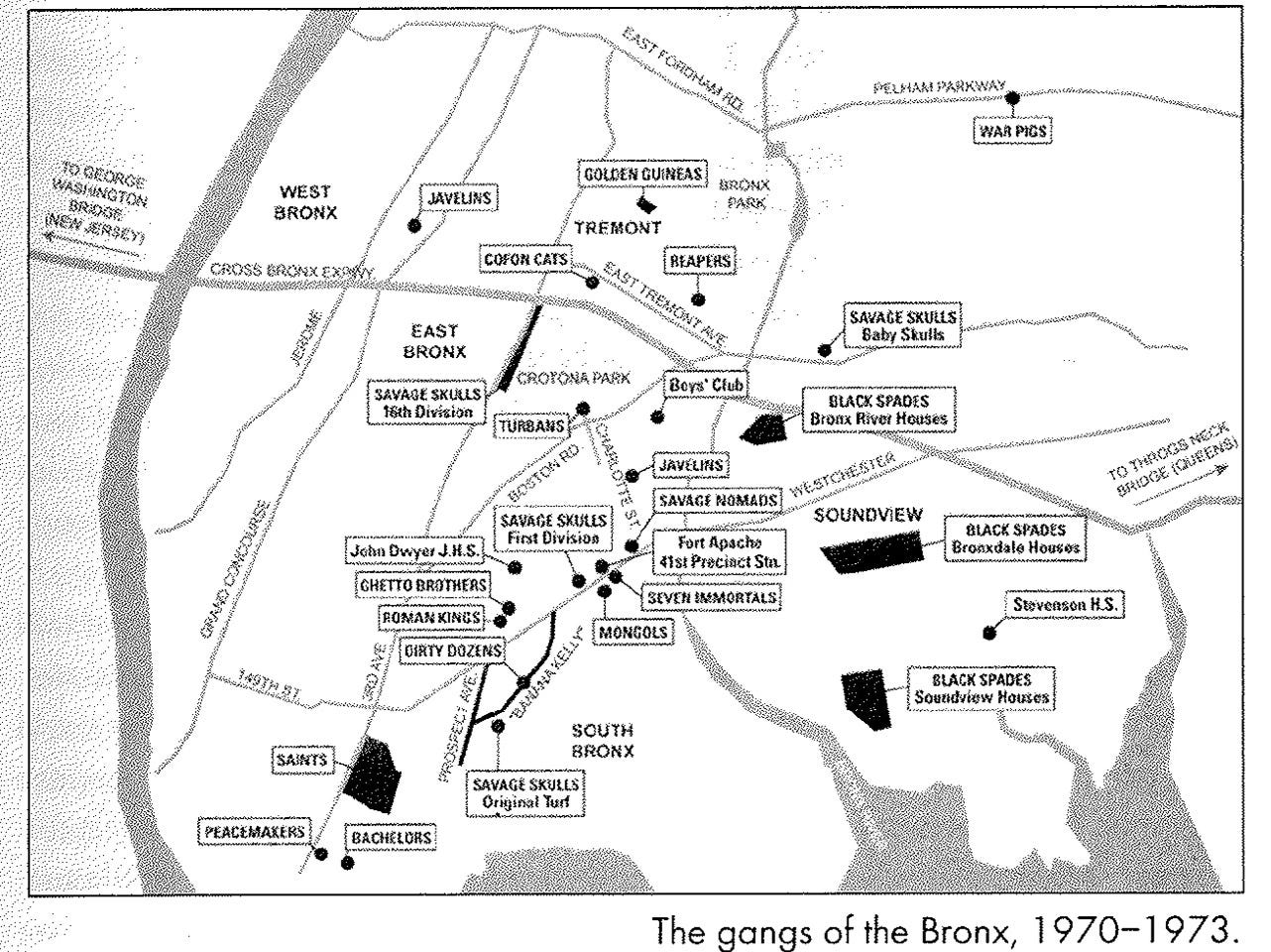

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the streets of the South Bronx were largely controlled by hundreds of gangs, including the Savage Skulls, The Slics, Black Spades, The Javelins, Savage Nomads, Seven Immortals, and the Ghetto Brothers. These gangs offered protection and community, functioning as surrogate families for thousands of unemployed and unsupervised teenagers. In his 2005 book Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, Jeff Chang called these young gang members “The children of Moses’ grand experiment.“

It is estimated that gang membership in the Bronx during this time totaled over 11,000, practically double the amount of police officers assigned to the entire borough.

Every gang laid claim to their turf, sometimes only a block long, and any incursion by a rival gang wearing their colors would result in a brawl, often turning deadly.

In three years, the gangs colonized the borough. Gang colors transformed the bombed-out city grid into a spiraling matrix of beefs. "If you went through some-one's neighborhood, you were a target. Or you had to take off your jacket," Carlos Suarez, the president of the Ghetto Brothers, recalls. "If you got caught, they beat the hell out of you.2

“BLACK BENJIE”

In a landscape dominated by teenagers, 25 year old Cornell “Black Benjie” Benjamin was an anomaly. Most gangs had warlords, but the Ghetto Brothers gave Benjamin the role of peacemaker. By the early 1970s, the Ghetto Brothers, who had nearly 1,000 members throughout the city, had transformed into more of a political organization in the mold of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. They focused on improving their neighborhoods by organizing clothing drives, advocating for better health care, and trying to get more opportunities for local kids.

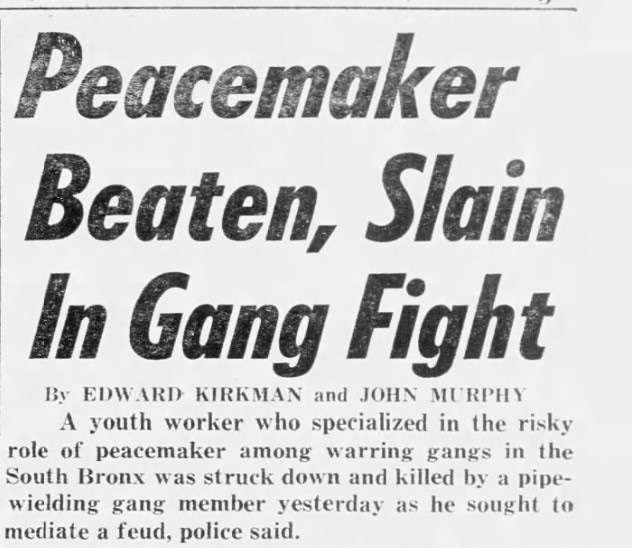

When word got out that members from the Seven Immortals, Black Spades, and the Mongols were jumping kids at nearby Horseshoe Park, “Black Benjie” and a small contingent of Ghetto Brothers tried to broker a peace. Their entreaties for a nonviolent resolution fell on deaf ears, and “Black Benjie” was beaten to death with a pipe.

In the aftermath, several members of the Ghetto Brothers called for an all-out war. However, Benjie’s mother, Gwendolyn Benjamin, urged the gang to reconsider, saying, “No revenge, Benjie lived for peace.”

This prompted the leaders of the Ghetto Brothers, Benjamin "Yellow Benjy" Melendez and Carlos “Karate Charlie” Suarez, to reach out to the leaders and warlords of several of the most prominent gangs in the Bronx and get them to agree to a sit-down at the Hoe Avenue Boys Club of America.

On December 8, 1971, mobbed by throngs of reporters and flanked by snipers on nearby rooftops, more than 150 gang members brokered a treaty and an alliance that would lead to a significant de-escalation in gang violence. Many people believe that the relative peace that the treaty engendered, which allowed for the free passage and intermingling of people from different blocks and communities, created the necessary environment for hip-hop to begin to take root.

The 1993 documentary Flyin’ Cut Sleeves by Henry Chalfant and Rita Fecher (who taught in the South Bronx during the late sixties and early seventies) follows the lives of some gang members over twenty years featuring footage from the historic Hoe Avenue summit.

Last year, East 165 Street at Rogers Place in Longwood was officially renamed Cornell “Black Benjie” Benjamin Way.

CASA AMADEO

Just a few blocks away, there is another intersection renamed for a famous Longwood resident. In 2014, the corner of Longwood Avenue and Prospect Avenue was renamed Miguel Angel "Mike" Amadeo Way.

90-year-old Miguel Amadeo is a prolific Puerto Rican songwriter whose compositions have been performed and recorded by artists like Willie Colon, Hector Lavoe, Celia Cruz, and Danny Rivera.

He also owns and runs the famous Casa Amadeo, the oldest continuously operated music store in NYC. The first iteration of the store was opened in 1927 in East Harlem by famous Puerto Rican composer Rafael Hernández and his sister Victoria. In 1941, they opened another store at 850 Longwood Avenue, quickly establishing itself as the heart of the city’s Latin music community.

Musicians went to the record stores looking for orchestras and conjuntos (musical groups) that were in need of instrumentalists. Music stores such as Casa Amadeo also became gathering places for musicians, knowing they could find work either from record companies looking for session players or from bandleaders looking for instrumentalists. The major record companies, such as Victor and Columbia, depended on store owners to act as "middlemen" in obtaining musicians for recordings and to gauge the community's musical tastes as to what might sell: and some record stores produced records right on the premises. To help ease the difficulties of being transplanted from Puerto Rico, record stores, along with institutions such as hometown social clubs, were places where new migrants flocked to hear and buy the sounds of home.3

After working there for nearly a decade, Mike bought the music store in 1969 and has worked there six days a week ever since. While the rest of the neighborhood was beset by fire and gang violence, Amadeo kept his store running.

Casa Amadeo was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio starts outside a high school, running through some graduation protocols, continues past a playground, and lingers for a bit in the famous Casa Amadeo, still a thriving neighborhood gathering spot.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

There are several photographers who have documented the South Bronx and Longwood in particular.

In 2013, Joe Conzo, Jr., Ricky Flores, Angel Franco, David Gonzalez, Edwin Pagán, and Francisco Molina Reyes II had a group show called SEIS DEL SUR: DISPATCHES FROM HOME BY SIX NUYORICAN PHOTOGRAPHERS at the Bronx Documentary Center.

Since I’m not entirely sure which of their photos are from Longwood, I’m instead sharing two more photos from Camilo Jose Vergara, whose work in the South Bronx I have shared before.

The first is of the Manhanset Building on Longwood Ave. Casa Amadeo is on the other side of the same building. The second image is notable for all the fake window scenes painted on the vacant buildings. Painting over plywood-covered windows was the city’s superficial attempt at addressing urban blight in the 1980s.

Both images are from the Library of Congress Vergara collection.

NOTES

Benjamin “Yellow Benjy” Melendez, one of the founding members of the Ghetto Brothers and the man primarily responsible for brokering the Hoe Avenue Peace treaty, was also an accomplished musician. Benjamin and three of his brothers, all members of the Ghetto Brothers, formed a band that played a mix of Latin, soul, and funk music. Their musical talent surpassed their ability to come up with interesting names, as evidenced in the Ghetto Brothers' 1971 release called “Ghetto Brothers - Power-Fuerza” with the infectious track Ghetto Brothers Power.

Benjy and his brothers were also huge Beatles fans. They later went on to form Street the Beat, which is, to my knowledge, the only Beatles-inspired quintet featuring former gang members, firebreathing, mimes, and a cardboard box drumkit. Good luck not getting Crazy Boy stuck in your head. Seriously, you’ve been warned.

The meeting at Hoe Avenue was the inspiration for Cyrus's memorable speech in the cult classic movie The Warriors. Can you dig it?

Here’s a playlist of music from Longwood including compositions by Miguel Angel "Mike" Amadeo, Rafael Hernández, and the Ghetto Brothers. (Apple Music version )

Rubble Kings is a 2010 documentary that explores the South Bronx in the sixties and seventies:

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/10/10/nyregion/south-bronx-neighbors-hold-devastation-at-bay.html?unlocked_article_code=1._k0.IMFh.0U6F-R013k9C&smid=url-share

Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation

https://www.nps.gov/places/casa-amadeo.htm

-“A more foul and unpleasant spectacle has never been seen in New York.” Hornblow didn't know an awful lot about the city's history, it appears.

-A lot of those '60s and '70s gang names could also have served as names for the rock and soul/funk bands popular at the time (though probably not the Savage Skulls).

-It hurts me to see the Prospect Theatre as a vacant shell of what it had once been. I imagine it has company elsewhere in the city amongst the ones whose buildings haven't been torn down yet.

I dig this indeed