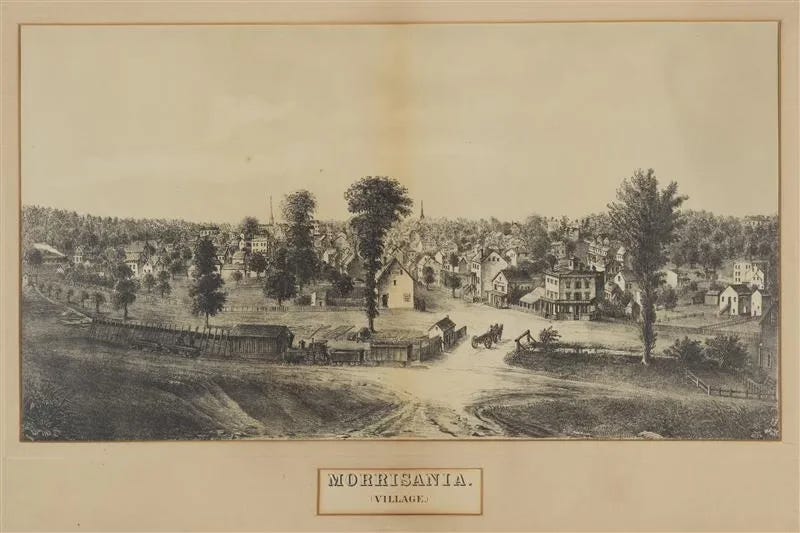

Morrisania was once part of the Morris estate, a 2,000-acre parcel of land encompassing much of the South Bronx. Today, the neighborhood’s borders are roughly formed by the Cross-Bronx Expressway to the north, Prospect Avenue to the east, East 162nd Street to the south, and Webster Avenue to the west. Crotona Park East, which I covered early in the summer, shares its western border with the neighborhood.

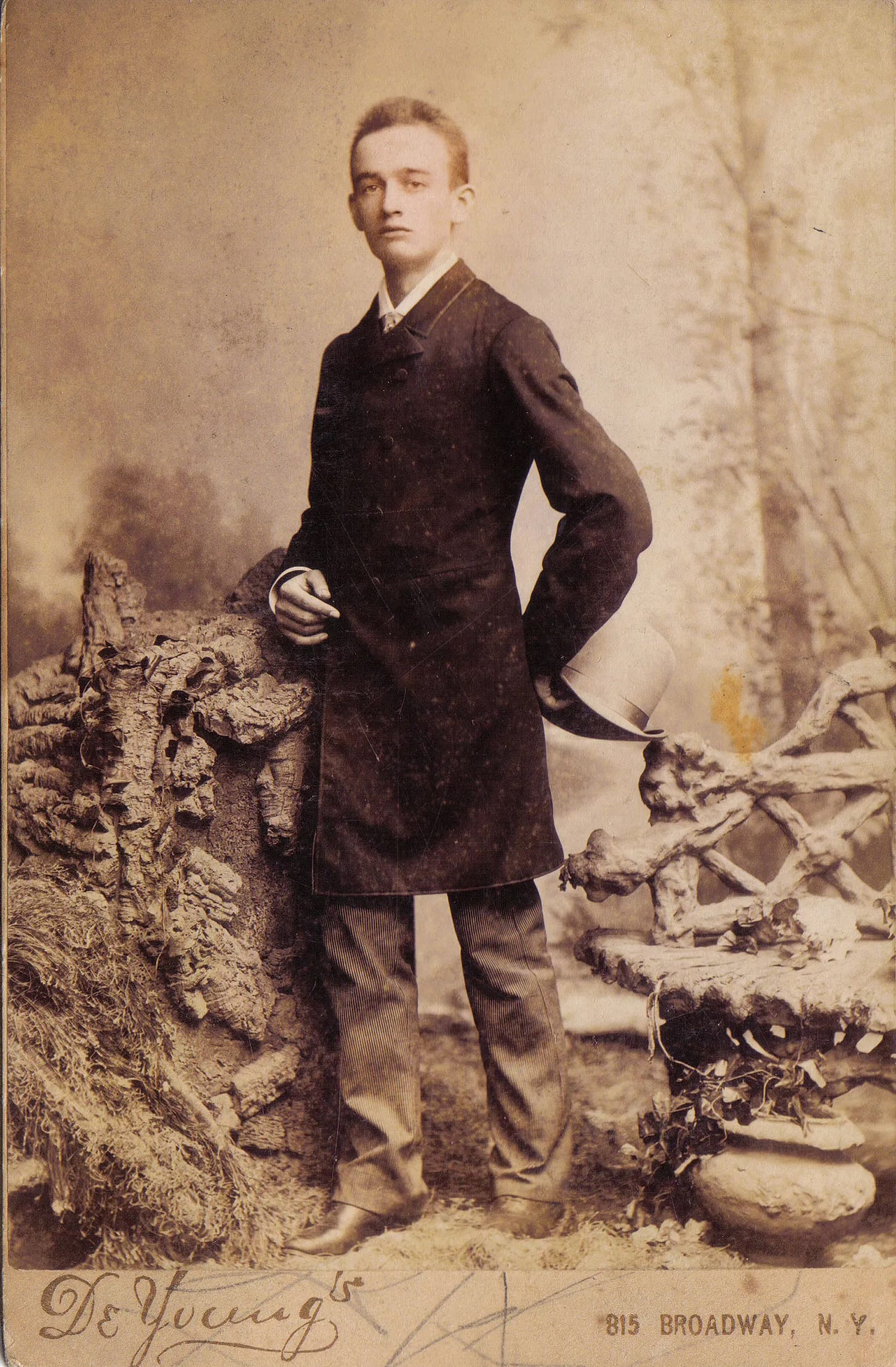

In 1670, Colonel Lewis Morris and his brother, Captain Richard Morris, purchased twelve square miles of land formerly owned by the Bronx’s namesake, Jonas Bronck, who had himself acquired the land from the Lenape.

The second Lewis Morris received a patent in 1697 and became the first lord of the manor of Morrisania. The third Lewis, besides being one the signers of the Declaration of Independence, unsuccessfully tried to convince the federal government to locate the nation’s capitol in Morrisania, touting the area’s "healthfulness and salubrity.”

Several other Morrises lived in Morrisania, not all of them named Lewis. There was Gouverneur Morris, the politician largely responsible for the “We the People”preamble in the US Constitution. Close readers of The Neighborhoods may also remember him as the person who died after trying to clear his urinary tract blockage with a whalebone.

His son, Gouverneur Morris Jr., was the Vice President of the New York & Harlem Railroad, and he convinced the company to build a railroad from Port Morris to Morrisania, putting an end to the days of health and salubrity.

The extension of the Third Avenue Elevated into the Bronx, followed by the subway in 1904, precipitated a flurry of development. A new commuter class who could now get into Manhattan quickly, filled the many three and four-story residences that sprouted up in the former pastoral lands of the Morrisania manor.

FIRST WAVE

The first wave of settlers were German immigrants, including Friedrich Trump, who settled on Westchester Avenue, where he plied his trade as a barber. Trump (formerly Drumpf) had tried to return to Germany but was denied his request for naturalization as he was seen to have avoided the country’s compulsory military service requirement. If only Friedrich had thought of the bone spurs excuse so effectively deployed by his grandson.

Most of Morrisania’s housing stock had been built before zoning laws required upper story setbacks and larger rear yard spaces. They were also built before elevators. After the Great Depression, landlords were faced with a glut of vacancies in these older buildings and they began advertising their apartments to “select colored tenants.” Many families from Harlem, wanting better schools, cleaner streets, and larger apartments, made the move north. In the ’30s, what had by then become a largely working-class Jewish neighborhood started its transformation into the Bronx’s most populous African American neighborhood.

According to author Mark D. Naison, what made Morrisania unique was that, unlike most other parts of the city, the new residents integrated relatively easily, a transition he attributes to the neighborhood’s working-class socialist roots.

Morris High School, which counts Colin Powell, Milton Berle, and Fat Joe among its alumni, was for a while the most integrated high school in the country.

Don't Push Me 'Cause I'm Close To The Edge

Though you rarely hear about it today, Morrisania was one of the epicenters of American music. Music clubs like Sylvia's Blue Morocco and Club 845 hosted some of the biggest names in jazz, including Nancy Wilson, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, John Coltrane, and Charlie Parker.

Herbie Hancock used to sleep on Donald Byrd’s hide-a-bed in his Morrisania Bronx apartment. Jazz pianist Elmo Hope lived on Lyman Place (now known as Elmo Hope Way), where Thelonius Monk was a frequent visitor.

At the same time, Morissania was a doo-wop hotbed with groups like The Wrens, The Chords, and The Chantels (the first female doo-wop group) all hailing from the neighborhood. The Tropicana and the Embassy Ballroom were host to some of the biggest Latin music stars like Tito Rodríguez, Celia Cruz and Tito Puente. The neighborhood’s integration made it a true musical melting pot throughout the middle of the twentieth century.

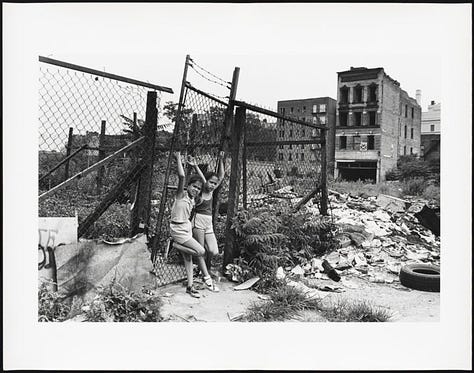

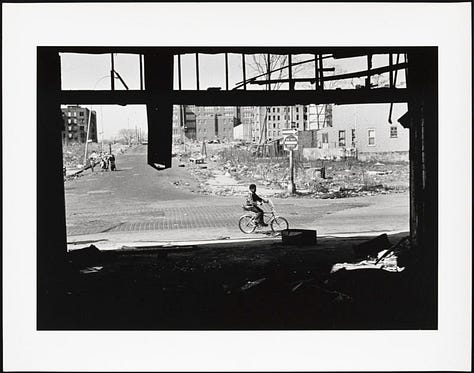

Then, the well-documented arson and disinvestment of the South Bronx in the late 1960s and the 1970s destroyed 40 percent of Morrisania’s housing stock and caused the exodus of more than half of the population. With no audience and, in some cases, no buildings, the clubs shut down.

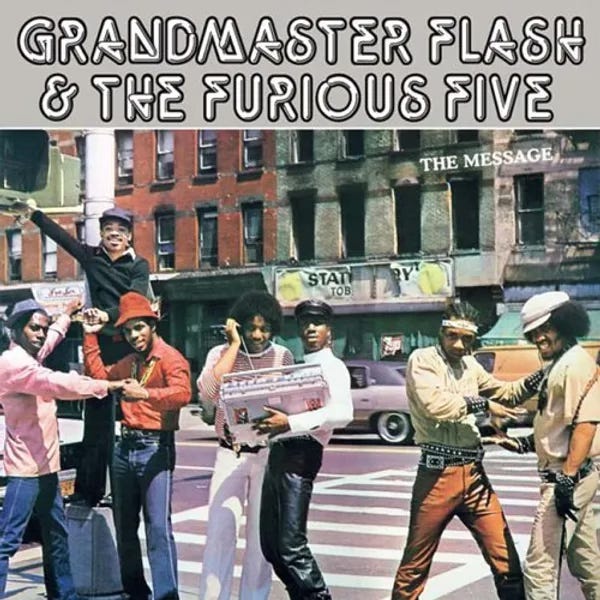

But in the late seventies, a new cultural movement began to take root in Morrisania. Joseph Saddler, aka Grandmaster Flash, used to hold court on the asphalt playground at Morrisania’s Public School 63 better known as 63 Park. He would set up his turntables, tap the light poles to power his PA, and draw huge crowds for his park jams, earning him a place among the pantheon of hip hop greats, part of the “holy trinity” that also includes DJ Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa.

Sylvia Robinson, who had previously owned the Blue Morocco club, started Sugar Hill Records. In 1982, she released Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message,” whose title track is often cited as the greatest hip-hop single of all time and one of the first to feature socially conscious lyrics

Broken glass everywhere

People pissin' on the stairs, you know they just don't care

I can't take the smell, can't take the noise

Got no money to move out, I guess I got no choice

Rats in the front room, roaches in the back

Junkies in the alley with a baseball bat

I tried to get away but I couldn't get far

'Cause a man with a tow truck repossessed my carDon't push me 'cause I'm close to the edge

I'm trying not to lose my head, ha-ha-ha-ha.

KRS-One is also from Morrisania. The rapper was discovered at the Franklin Armory men's shelter by his future Boogie Down Productions’ collaborator, Scott La Rock, who was working at the shelter as a social worker.

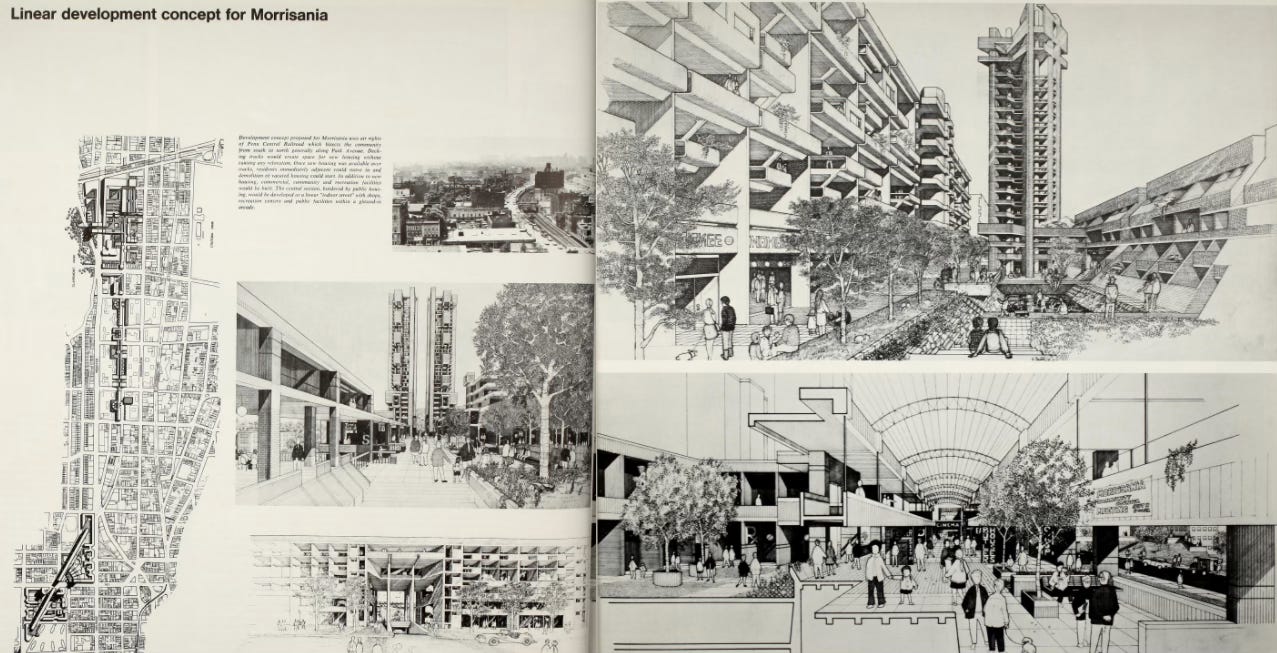

Morrisania Air Rights

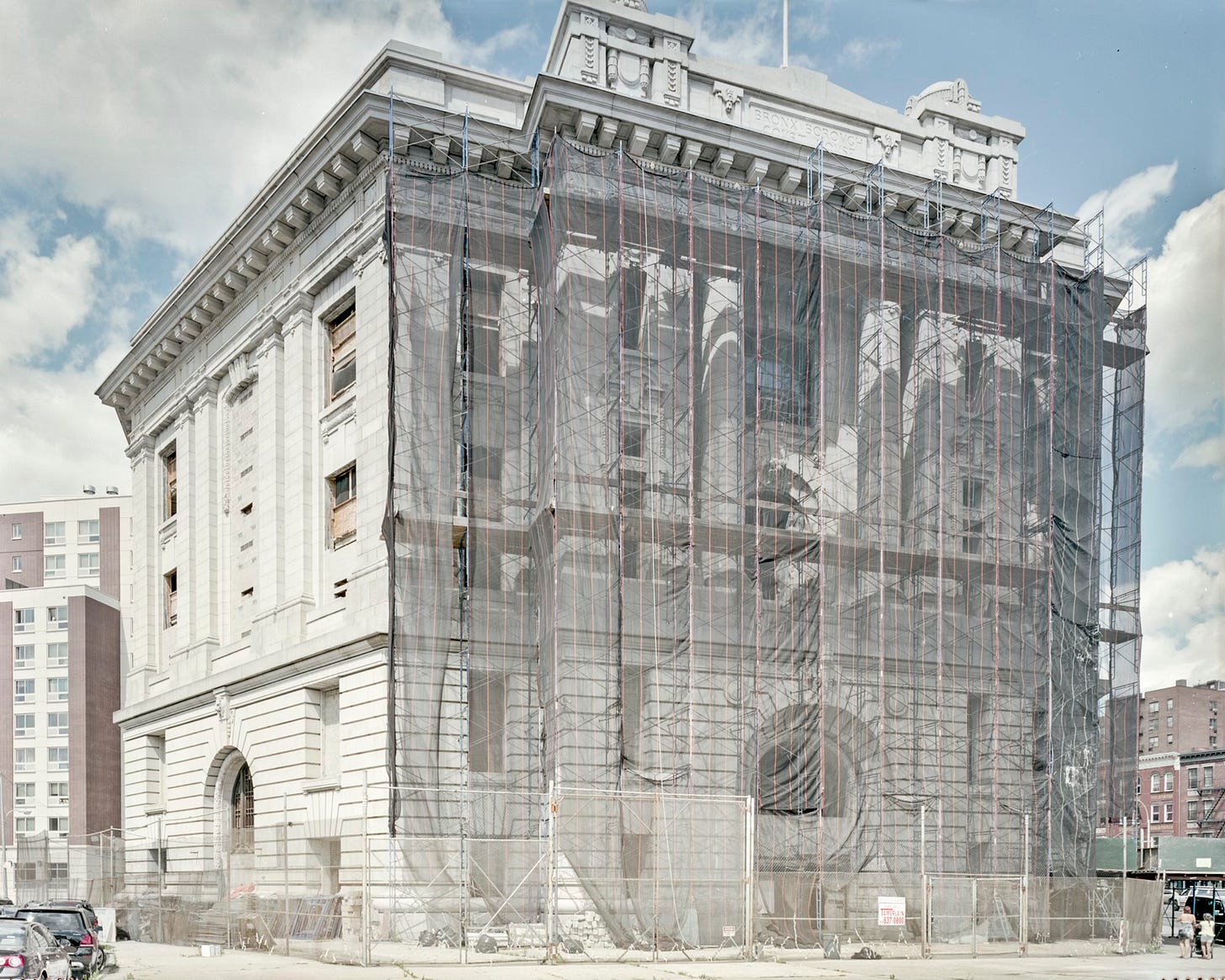

When it was time to name the three-building project at the southern corner of Morrisania, the PR department at NYCHA had run out of steam.

Housing projects built in previous decades had names like the James Weldon Johnson Houses or the Walt Whitman houses, but in the ’70s, the utopia promised by the “towers in the park” model of public housing had failed to materialize, and nobody wanted a housing project named after them.

NYCHA decided to dispense with the honorifics altogether and went with more prosaic names like Lower East Side Infill #1, South Bronx Area Site 402 and the “starkly utilitarian yet somehow enigmatic” Morrisania Air Rights.1

In an era when Robert Moses’ slum clearance approach to development had fallen out of favor, NYCHA had to figure out how to get approval to build the massive project. Using an innovative construction technique employing lightweight horizontal steel trusses, they were able to build in the undeveloped airspace over the Metro-North tracks, to which they acquired the rights, hence the name.

The most striking features of the Morrisania Air Rights buildings are the flying buttress appendages that extend like surface roots from the buildings’ bases.

The windowless sides of the buildings reveal a patchwork palimpsest of repair work, contributing to the building’s slightly dystopian presentation.

There are several proposals for improving the project, including painting murals over the sides, opening up the largely abandoned ground floor to commercial uses, and softening the concrete formwork with landscaping.

NYC Urbanism has a great piece on the Air Rights complex if you want to read more.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

I spent the majority of my time editing out my sniffles from this week’s field recording that meanders through the somewhat chaotic streets of Morrisania. Hope I got all of them!

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I’m not an artist; I’m a messenger.

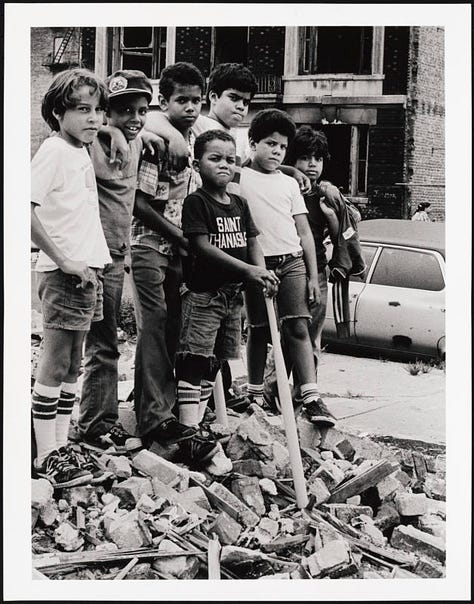

Mel Rosenthal was born in Morrisania in 1940. Rosenthal got his Ph.D. in English literature and American studies at the University of Connecticut in 1967 and taught for several years at Vassar College. After a stint working as a medical photographer at a Tanzanian hospital, he returned to New York in 1975. When he saw how much his neighborhood had changed in the intervening years, he was compelled to document it. Rosenthal’s book “In the South Bronx of America” was published in 2000. Rosenthal’s pictures stand out because they not only depict the devastation of the South Bronx landscape but also the resiliency of the residents who remained.

NOTES

I learned a lot from Before The Fires, an oral history of Morrisania from the 1930s to the 1960s compiled by Mark Naison.

You can buy a Grandmaster Flash action figure on Amazon which is pretty cool or you can commission a custom Grandmaster Flash action figure which is infinitely cooler.

I made a playlist of Morrisania music:

Complex called the 1982 cult classic, Wild Style, “a Magna Carta of sorts, a founding document for a culture that at that time was unknown beyond the streets of the five boroughs.”

Many of the film’s scenes are shot in Morrisania and feature Grandmaster Flash, Fab Five Freddy and the Rock Steady Crew. You can watch the whole movie on Youtube.

https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/03/31/the-curious-case-of-a-housing-complexs-puzzling-name/

The musical legacy of this neighborhood is a strong and important one.

Incredible post. How much time do you put into these? They are so deeply researched, beautifully written, and evocative. In awe!