Glendale - Queens

Celebrating one year of The Neighborhoods with Harry Houdini, Archie Bunker and an Uber Pretzel.

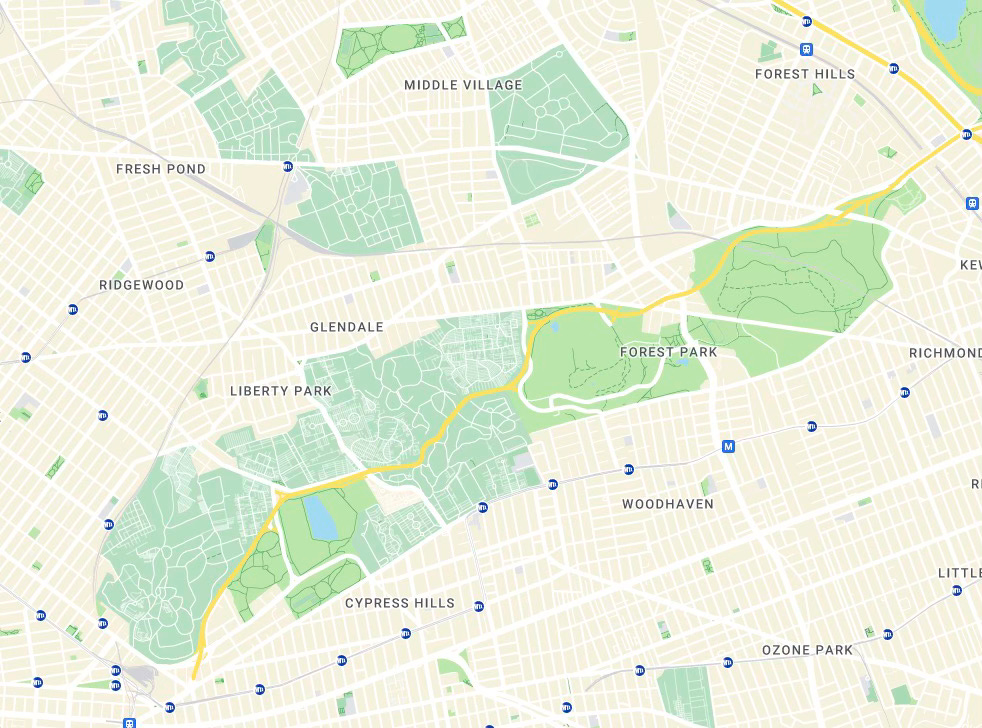

Glendale, surrounded by cemeteries and train tracks, looks to be practically dead center in the middle of New York City. Ironically, for a neighborhood that somewhat resembles a fish, it is about as far away from the water as any neighborhood in the city.

I embarked on this project one year ago this week in the “official” center of the city, Woodside, Queens, and 48 different neighborhoods later, I find myself back where I started. I am so grateful to all of you who have followed along over the past year. It has been a really fun, if exhausting, project to work on, and I genuinely appreciate all the unexpected support and feedback I have received!

TIGHTENING THE BELT

Back to Glendale. The neighborhood’s borders are roughly defined by the Long Island Rail Road to the north, Woodhaven Boulevard to the east, Fresh Pond Road to the west and several cemeteries to the south.

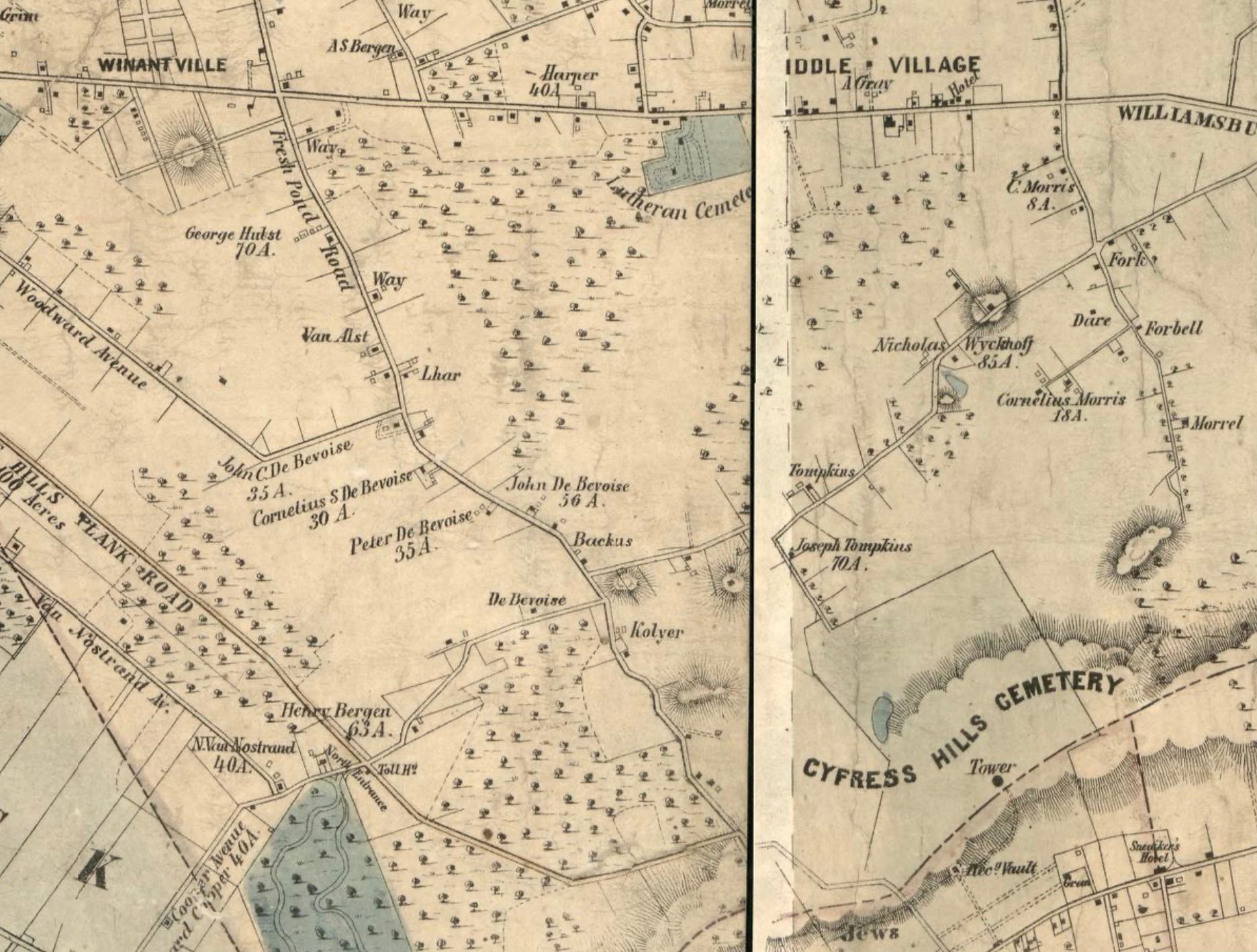

In the mid 1800s, Manhattan’s growth had exponentially surpassed the capacity of its graveyards and the city was desperate to outsource the interments of its former occupants. The small two acre graveyard at Manhattan’s Trinity church alone was overflowing with an estimated 125,000 bodies, many of them just inches below the surface.

Taking advantage of the ample open space outside of Manhattan, the Rural Cemetery Act was passed in 1847, resulting in the construction of 17 cemeteries straddling the Queens and Brooklyn border. I already covered this “verdant necropolis” known as the cemetery belt in the Cypress Hills edition of the newsletter.

While Cypress Hills sits right below the belt, Glendale is above. Actually Glendale is practically surrounded by cemeteries, so if you really wanted to stretch the analogy to its limits, you could say it’s the belt buckle.

OHIO

One man would who would not be deterred by the prospect of owning a patch of mosquito-infested swampland surrounded by cemeteries was developer George C. Schott. Perhaps that is because he didn’t have any say in the matter since the land was given to him as repayment for a debt.

In any event, Schott named the new neighborhood after his hometown making it, to my knowledge, the only NYC neighborhood named after a town in Ohio. By the way, if you do a search for George C. Schott, the search engine will repeatedly assume you are looking for Oscar winning actor George C. Scott and keep changing your query which is pretty ducking annoying. Since I was forced to view the search results anyway, I was intrigued to learn that the more famous George C. is interred in a cemetery right outside of Glendale…California.

PICNIC

After the wetlands were drained the area was predominately used for agriculture. By 1880, German immigrants accounted for one third of New York City’s population and many of them chose to settle in Glendale, opening hotels and breweries that quickly became a popular weekend draw. When a steam dummy trolley line started operating on Myrtle Avenue in 1893, the area really took off.

Steam dummies were steam locomotives disguised to look like regular passenger cars. It was thought the faux enclosures would ameliorate the locomotive’s terror-inducing effects on horses, but, as any dummy could tell you, it was the deafening sound and belching clouds of steam that made the trains scary, not their lack of wood paneling.

Most people who took the train to Glendale were coming to spend the afternoon in one of the neighborhood’s many picnic parks. I’m not entirely clear what differentiates a picnic park from any park where you can bring a picnic, but it seems to come down to beer. Many of these parks were owned by the breweries which used their pastoral location as a way to entice thirsty patrons — as if Germans needed added incentive to drink beer. Basically, a picnic park is a beer garden, or a beer dummy.

One popular picnic park was the 25 acre Schmidt’s Woods, owned by the Wells and Zerwick Brewery. Picnic goers could sit under the dappled forest light and enjoy a basket of soft pretzels washed down with an eighth-barrel of Welz and Zerwick lager for $1,1 which sounds like a pretty nice way to spend an afternoon.

Prohibitionists didn’t see it that way. After World War I, they used anti-German sentiment to paint the breweries and beer drinkers as unpatriotic. When the Volstead Act became law in 1920, the breweries and picnic parks shut down for good.

That’s a Real Hemmerdinger

In 1922, rag merchant Henry Hemmerdinger (who sounds suspiciously like a Roald Dahl character) purchased a large tract of land to build a rag processing factory. Apparently selling rags was a very lucrative business. When Hemmerdinger died (try saying that ten times quickly), the industrial park, which he named Atlas Terminals, had grown to 31 buildings and covered 786,000 square feet.2 Henry’s son took over and expanded the park further, attracting marquee tenants like Kraft, General Electric, and Westinghouse.

Today, the Hemmerdingers have transitioned from rags to real estate and most of the large industrial tenants have moved on. In 2006, Henry’s great grandson, Damon Hemmerdinger, converted part of the park into an open air mall or “lifestyle center” called The Shops at Atlas Park. The timing wasn’t great, and in 2009, Hemmerdinger announced that the family would be withdrawing from the project.

HOUDINI

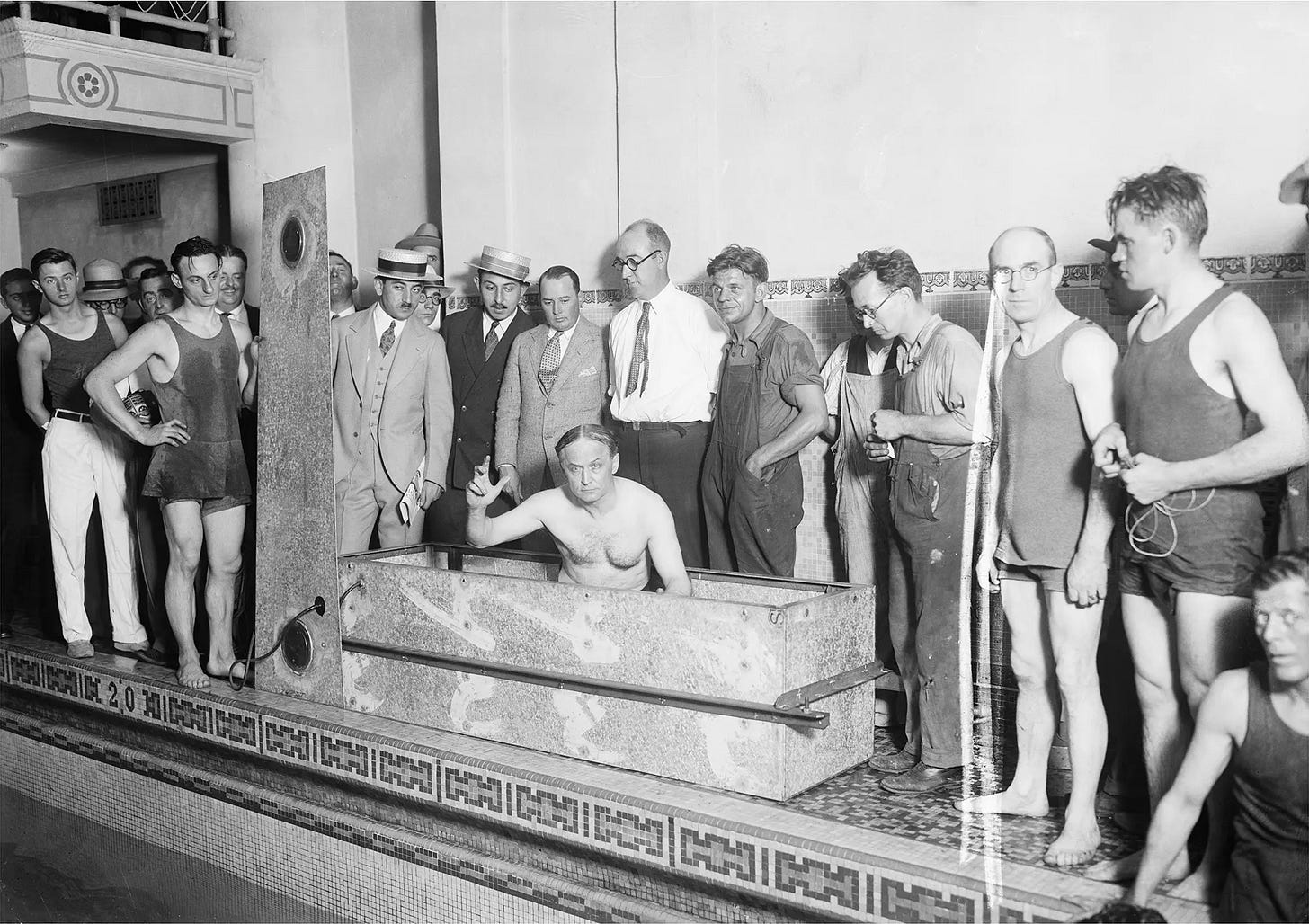

Glendale’s most famous resident didn’t move to the neighborhood until after his death. Master escape artist and illusionist Harry Houdini died on October 31, 1926, nine days after being punched multiple times in the stomach by McGill University student J. Gordon Whitehead. A few days prior, at a university lecture, Houdini, never one for modesty, claimed that he had abs of steel. Whitehead, who had attended the lecture, was hanging out with a couple of other McGill students in Houdini’s dressing room and asked him if the claim was true. When Houdini nodded yes, Whitehead, an empiricist, proceeded to deliver a flurry of punches to the reclining Houdini’s mid-section. A few days later, Houdini was dead from peritonitis, proof that it is easier to escape from a Chinese Water Torture Cell than a ruptured appendix.

At 7:10 PM on November 1st, a train pulled out of Detroit’s Michigan Central Station carrying Houdini's corpse in an air tight bronze coffin. He had recently spent ninety minutes in that same coffin at the bottom of a pool to prove that carbon monoxide poisoning was no match for the power of positive thinking.

Houdini had expressed his desire to be buried in the coffin and as luck would have it, it was already waiting for him in Detroit. All the other equipment from his show had already been sent back to New York, but somehow the coffin had been misplaced and had just resurfaced days before his death, saving a bundle in shipping fees.

Over 2,000 people attended Houdini’s burial in Glendale’s Machpelah Cemetery where he was interred in the family plot.

Last Sunday morning, after a couple of visits to the wrong cemeteries, I found myself at the entrance to Machpelah Cemetery. I was a little unsettled to see two men digging in the graveyard and hurriedly made my way to the Houdini family monument tomb located conveniently close to the gates. A rectangular plot of low grave markers led to a curved granite bench occupied by a statue of a bereft woman underneath a bust of Houdini

Between 1975 and 1993, the bust had to be replaced four times after being smashed or stolen. This was one disappearing act that the Society of American Magicians, of which Houdini was once the president, could not get behind. They stopped replacing the busts.

Instead, every year, to honor Houdini’s death, members of the society would tote the magician’s marble head to the grave for a broken wand ceremony and then pack it back up and bring it home. The broken wand ceremony is performed when a magician dies and, as the name suggests, involves the breaking of a ceremonial wand. Much like the sword breaking ceremony I wrote about last week, the wand is pre-filed for easy snapping. The first wand breaking ceremony ever performed was at Houdini’s funeral.

The monument remained headless until 2011, when a group of self professed “Houdini Commandos” from the Houdini Museum in Scranton, PA, orchestrated a brazen guerrilla bust restoration in broad daylight.

Armed with diamond bits, drills, a generator, quick drying cement and, of course, a bust, they restored Houdini’s head to its rightful place atop the Houdini/Weiss monument.3

One peculiarity about Houdini’s grave is that his wife Bess’ name is etched underneath his, but there is no listed date of death, only a 19 followed by two raised rectangles.

Because Bess was Catholic, she could not be buried in the Jewish Cemetery. Jewish law also dictates that caskets be made only out of wood and Houdini’s was solid bronze. It appears, that when it came to magicians at least, the rules were selectively enforced.

THOSE WERE THE DAYS

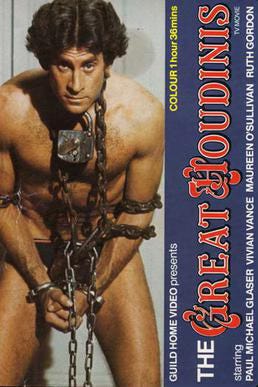

Speaking of Bess, Sally Struthers played the role of Houdini’s wife in the 1976 made for tv movie, The Great Houdinis. The movie starred Paul Michael Glaser (Starsky of Starsky and Hutch fame) and the promo features a semi-naked and shackled Glaser that does not feel made for TV, at least the channels we got when I was a kid.

Despite the amazing promo, Struthers is probably most famous for her role as Gloria in Norman Lear’s All in the Family. While the Bunkers were said to live at 704 Hauser Street in Astoria, the exterior of their house, featured in the opening credits, is in Glendale on 89-70 Cooper Avenue, across the street from yet another cemetery.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio starts out at the bar at Zum Stammtisch (more on that below), continues to the edges of the Long Island Rail Road tracks and ends up at Houdini’s grave.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Outside of the usual suspects, I couldn’t find any other photographers who have worked in Glendale. If anyone reading this has any suggestions, please let me know below.

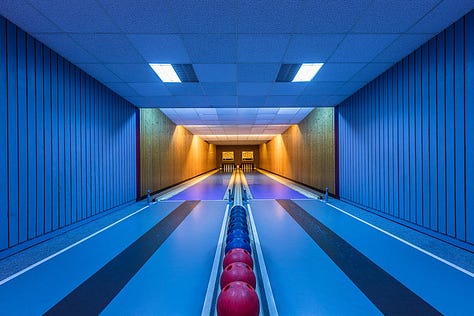

In my research I did, however, hear quite a bit about Glendale’s bowling history, with several little alleys tucked in and below German hotels and bars. That led me down a German bowling alley rabbit hole where I found out about a nine-pin bowling variation called "Kegelbahnen.” I wouldn’t be surprised if many of Glendale’s former lanes were of the Kegelbahnen variety.

Anyway, I found a project done by photographer Robert Goetzfried, executed with textbook German precision, documenting some of these amazing alleys in Germany.

NOTES

To celebrate one year of sending out newsletters, I’m taking one week off from writing them. I’ll be back on May 9th, or, if you observe, National Lost Sock Memorial Day.

Probably the closest you will get to the Glendale of late 19th century is by grabbing a stein and some schnitzel at neighborhood stalwart Zum Stammtisch. When I was photographing Glendale earlier this week, I debated whether or not I should pay the restaurant a visit. When it started to rain, the decision was made for me. If you are into taxidermied warthog heads, lederhosen and beer (and frankly, who isn’t?), this is your place. Don’t sleep on the Uber Pretzel - though you could, it’s huge.

In 1940, J.P. Morgan was living in Glendale on 88-28 Seventy-Fifth Avenue. This J.P. Morgan however, was not the captain of industry who lived in Murray Hill. The Glendale Morgan, described as a “tallish fellow in his middle thirties, who parts his hair in the centre, and wears gray spats,“4 operated an oil heating company by the name of J.P. Morgan & Co that he incorporated in 1933. This caused considerable confusion when the more famous J.P. attempted to incorporate his bank with the exact same name as the already existing oil company - a legal technicality that was quickly smoothed over by the state legislature. This wasn’t the first time the Glendale Morgan was mistaken for his Manhattan counterpart. He would occasionally receive calls from people who had looked him up in the phonebook asking for financial advice. Whenever he got one of those calls, he would simply say, "This isn't the banker" and hang up, which, coincidentally, is how I often end my phone calls too.

https://qns.com/2019/06/an-old-saloon-the-woods-of-glendale-and-local-beer-history-our-neighborhood-the-way-it-was/

https://junipercivic.com/juniper-berry/article/atlas-terminals-throughout-the-years

https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/24/houdini-returns-of-course/

The New Yorker, March 23, 1940 P. 13

“Whitehead, an empiricist,” Indeed!

Another amazing set of stories about New York. Congratulations on your first year of posts. The research is impressive, week after week!