Greetings from the city that currently holds the ignominious distinction of having the worst air quality in the world. Before the smokey haze that rekindled our K95 love affair descended upon the city, I revisited the neighborhood of Cypress Hills in Brooklyn.

Drop a reference to Cypress Hills into a conversation, and the first thing that comes to mind, for people of a certain age is likely this:

Those less familiar with the first hip-hop group to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame may think of the neighborhood on the Brooklyn/Queens border that shares the same name. In the early 18th century, present-day Cypress Hills was part of the larger settlement of New Lots, farmed by the Dutch, French, and English. The Jamaica Plank Road, a wooden toll highway connecting Brooklyn to Queens, was built in the early 19th century. It ran through the middle of the neighborhood, marking the beginning of the area’s development.

When the Rural Cemetery Act passed in 1847, the neighborhood’s population, and dead, grew exponentially. In 1886, New Lots, including Cypress Hills, was annexed by the city of Brooklyn, furthering its transformation from rural to urban. In 1894, The Brooklyn Eagle wrote, “The fields of corn and cabbage have been superseded by cottages.”

Only the Dead Know Brooklyn

Passage of the Rural Cemetery Act paved the way for the commercialization of cemeteries. Until then, burials had been relegated to churchyards or residential plots. Overcrowded graveyards in Manhattan, with coffins often stacked five or six deep, raised concerns about disease spread through groundwater, and the foul stench emanating from the overfilled cemeteries couldn’t have been pleasant.

The source of the smell was unmistakable–the decomposition of tens if not hundreds of shallowly buried corpses.

The Rural Cemetery Act, coupled with an 1852 law prohibiting new burials in Manhattan, created the “Cemetery Belt,” a network of 17 cemeteries along the borders of Queens and Brooklyn. Between 1854 and 1856, in the ultimate NIMBY move, more than 15,000 bodies were exhumed and moved to Cypress Hills Cemetery.

Under cover of darkness the creaking horse-drawn wagons are loaded onto the ferry. Once across the river, they lumber through the sleeping countryside, finally coming to a halt on Queens hillsides where graveyard workers unload their strange cargo — thousands of skeletons and coffins exhumed from Manhattan churchyards.1

Ultimately, Cypress Hills’ cemeteries are estimated to have reburied the remains of over 35,000 people disinterred from their original gravesites in Manhattan.

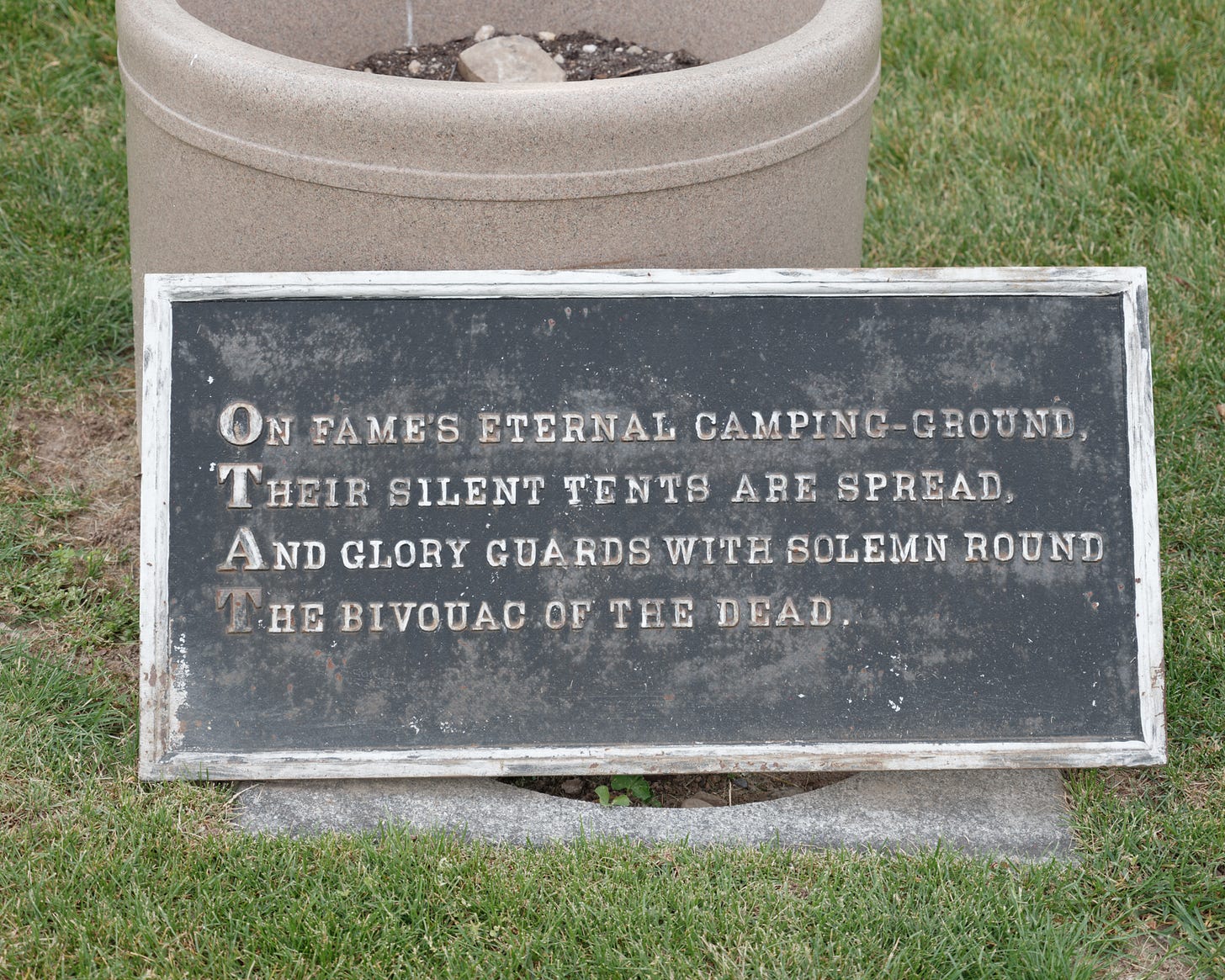

Fame’s Eternal Camping-Ground

The founders of Cypress Hills were not interested in the cemeteries of yesterday; they were planning the cemetery of tomorrow. They searched for a site where richly wooded hills and dells, with here and there a sequestered lake or pond, would enable them to attain the seclusion, privacy and pensive tranquility of the ideal “rural” cemetery.

This quote from the Cypress Hill Cemetery website speaks of the cemeteries’ dual function as both burial grounds and as pastoral escapes from the chaos of the growing city.

Last week I decided to see what all the fuss was about and visit one of the cemeteries in the neighborhood, the Cypress Hill National Cemetery. National cemeteries were Established in the 1860s to bury the thousands of soldiers killed during the Civil War. In addition to Civil War veterans, the cemetery serves as the final resting spot for soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Spanish-American War, and the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

When I arrived at the cemetery, I was surprised by the flurry of activity in what was advertised as the Bivouac of the Dead. The grounds were teeming with people, kids running down the white tombstone-lined paths, grandparents clutching bunches of tiny, furled flags, and dozens of people hunched like gleaners among the graves. I felt like I had stumbled upon a coimetrophilia2 convention.

Sensing my confusion, a man came over and explained that this was a Memorial Day clean-up event. Volunteers were collecting the over 15,000 flags they had set out the previous weekend. He then invited me to take part in the de-flagging. Pull them out, gather them into groups of ten, wrap the flags around each other, and place them in the large blue Tupperware bins placed throughout the graveyard. Easy enough. I was feeling quite pleased with my freshly plucked bounty of 20 flags, but just as I got to the bin, I was cut off by a 9-year-old boy who dumped a heaping stack of at least 80 flags into the container. I realized there was no competing with the fervor of a Cub Scout going for his Webelos badge and quietly made my way out of the cemetery.

We ain't goin' out like that

We ain't goin' out!

I recently came across a story about ten nuns who were driven from their Cypress Hills monastery when the outside noise proved too much to bear. The nuns who tout their “vigorous use of the hammer and saw, garden fork and hoe, typewriters, mops and other implements of toil” seem like they can handle more than a bit of discomfort. However, they were ultimately done in by the all-night subwoofer soundtracked barbecues in adjacent Highland Park.

I thought I would visit the monastery to investigate. When I got there, I noticed an RV set up right across from the nun’s residence, and, just as they had reported, it was emitting an incredibly intense, window-rattling bassline that seemed in danger of setting off any nearby car alarms. My visit took place at 7:30 AM on a Saturday. I can’t imagine what midnight on a typical Friday is like. To make matters worse, the nuns sometimes found beheaded animal carcasses just outside the monastery’s 13’ concrete walls, sacrifices from local Santeria adherents. According to Jim Krug, a lay worker with the church:3

“They [Santeria practitioners] think there is some type of spiritual force here. Some kind of vortex. But of course, the sisters see it in a very different way. They see it as evil.”

On that same Saturday morning, no headless chickens were in evidence. Maybe the spiritual vortex had lost its potency in the nuns’ absence. Or perhaps nobody wanted to be within earshot of the dub house remix of Despacito.

In the end, the sisters did, in fact, go “out like that” and, courtesy of the Diocese of Scranton, have found themselves a new temporary home in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the ten nuns have undertaken plans to build a new 70,000 square-foot monastery, drawing on Renaissance and baroque sources, in particular the Spanish cloisters in Avila and Toledo, for a cool $25 million. Insane in the Brain.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

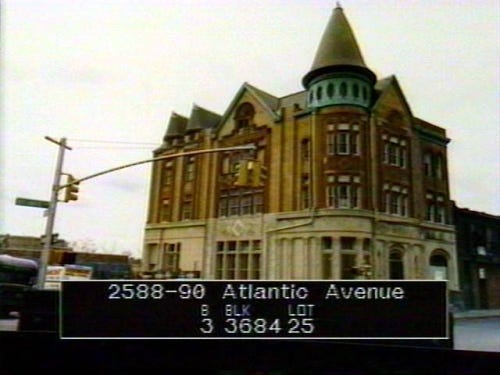

Cypress Hills isn’t just graveyards and monasteries, it has churches too. It’s also home to an ethnically diverse population and is notable for its eclectic architecture and the constant rumble of the overhead J and Z trains running down Fulton Street.

Featured Photo

In keeping with the cemetery theme, here is a picture of Biggie Smalls by Michael Lavine in the Cypress Hills National Cemetery. You can read more about the shot in the Guardian, part of their always fascinating My Best Shot feature.

NOTES

Amy Waldman wrote an excellent piece on the Yellow Rose bar in Cypress Hills, Bar Is a Borderline Case.

Addie's golden-hued hair is piled, curled and sprayed at a precarious angle. Her blue eyes loom large from a small, lined, heart-shaped face. Her voice rasps from a thousand thin brown cigarettes, clutched in long red nails.

The bar bears a feminine imprint: floral place mats; a fresh smell in the spotless bathrooms. She keeps the television turned to the History Channel and pictures of Washington and Lincoln on the walls. Books fill the time that customers once did.

So good. Sadly, the bar is no longer around.

Love this 1996 cameo by Cypress Hill on the Simpsons.

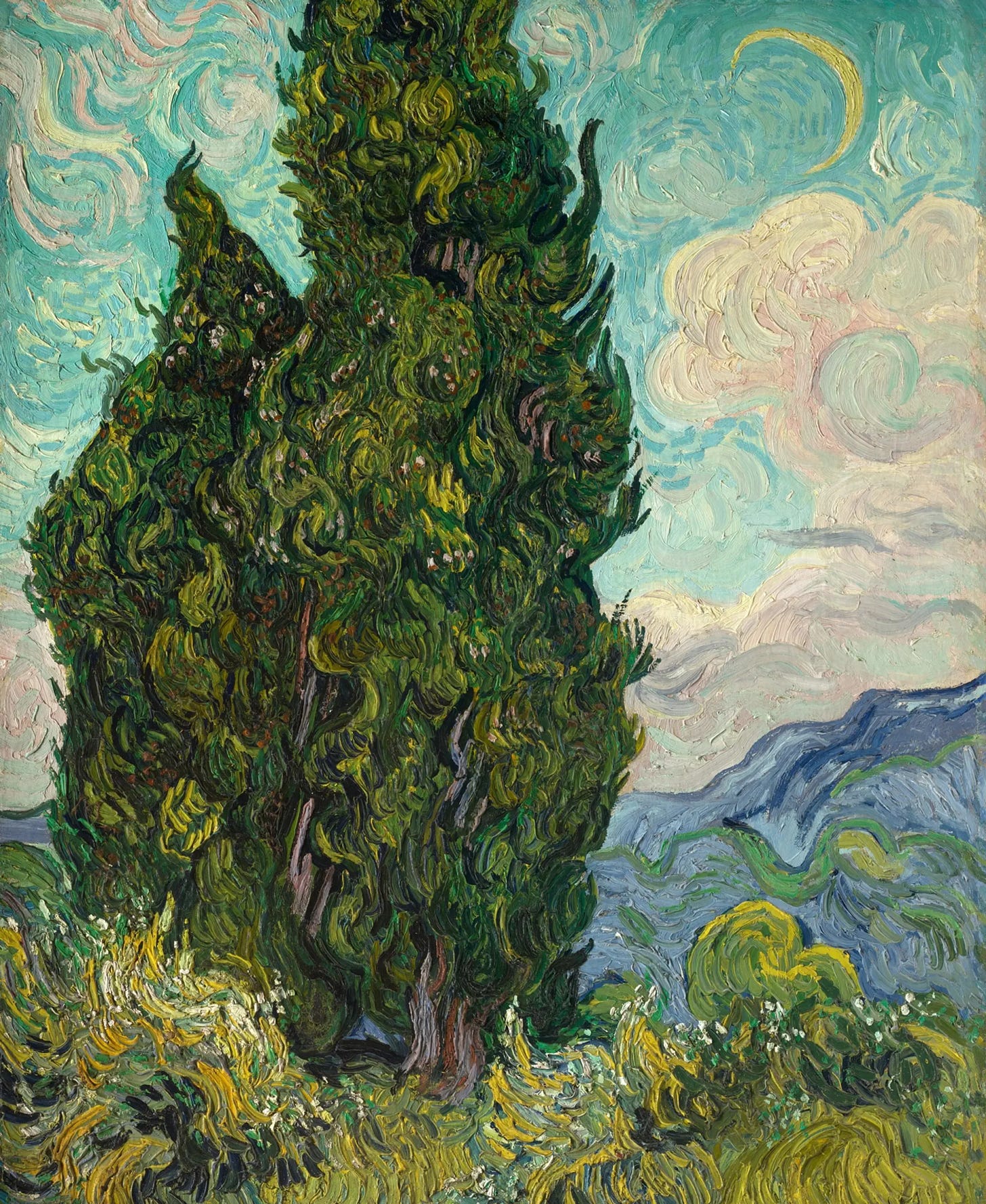

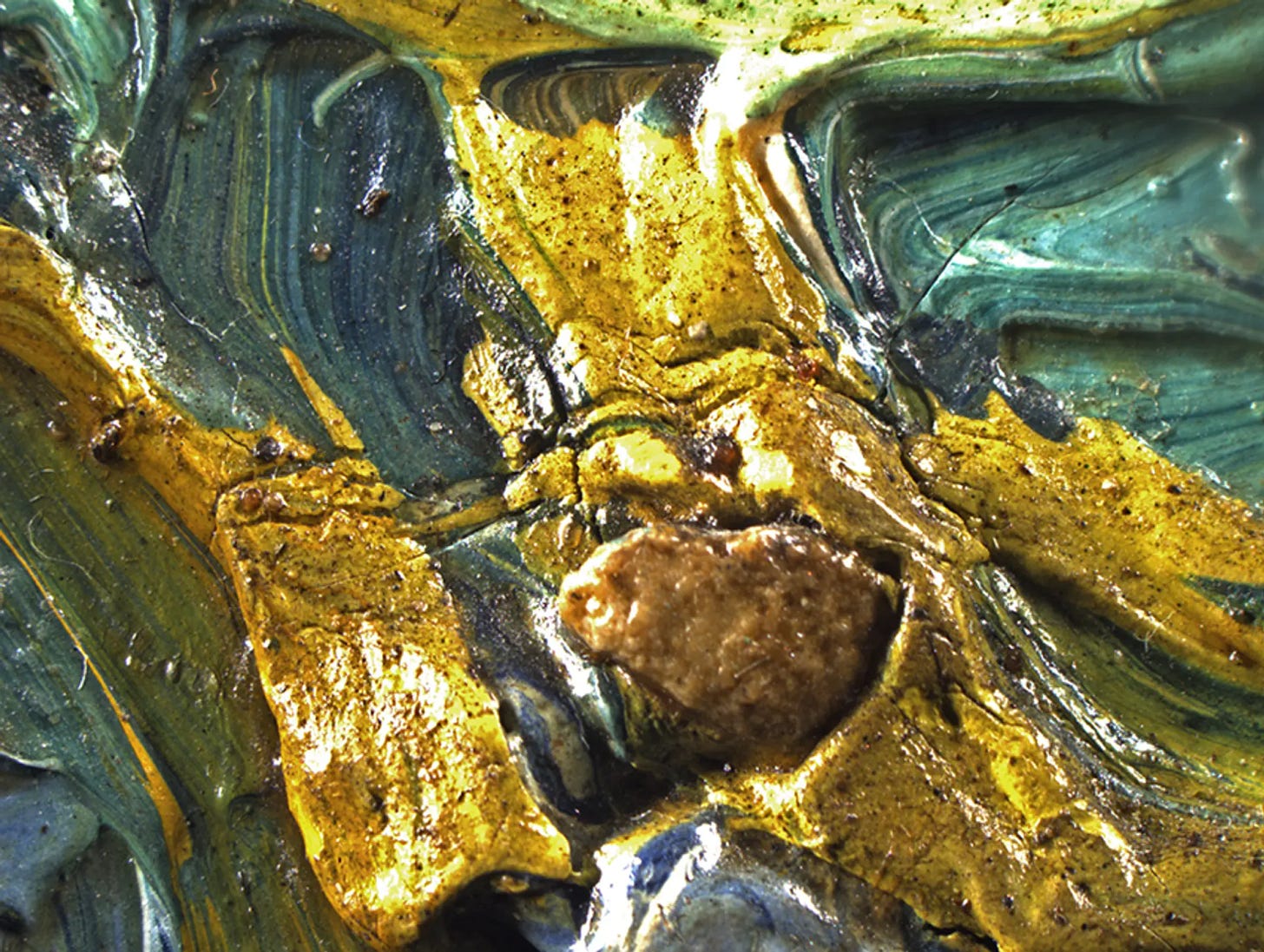

Speaking of Cypresses, for those of you in the city, there is the Van Gogh Cypresses exhibition through August 27th at the Met, including this painting, Cypresses (June 1889), notable for the presence of “scores of sand particles and small limestone pebbles, the largest 6mm in diameter, embedded in the paint, along with vegetal matter.”

The pebbles were discovered by using a microscope and with “X-ray fluorescence mapping,” exactly as Van Gogh intended his work to be viewed.4 Scholars believe that the canvas was most likely blown over by a gust of wind, though no one will ever know for sure.

Amon, Rhona. 2006. The Cemetery Belt: Why does Queens have so many cemeteries? Answers go back to mid-1800s Manhattan in Newsday

coimetrophilia, koimetrophilia (noun); coimetrophilias, koimetrophilias (pl)A special fondness and interest in cemeteries or graveyards.

https://wordinfo.info/unit/520

https://thetablet.org/neighborhood-decline-prompts-relocation-of-carmelite-nuns/

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/11/arts/design/van-gogh-cypresses-met-museum.html