A quick note that I am travelling to Mexico City (by way of Atlantic City) and will be taking next week off. I will send out my usual bonus Monday newsletter to paid subscribers (thank you!). For those of you keeping track, this week’s edition is the 93rd neighborhood I have covered so far. If you have any recommendations for Mexico (or Atlantic) City, please leave them in the comments below!

Bulls Head, in the middle of Staten Island, is one of those quasi-suburban neighborhoods that sprouted up immediately following the completion of the Verrazano Bridge in 1964. Before the construction of the bridge, the area was predominantly farmland, where Italian and especially Greek farmers grew vegetables like lettuce, tomatoes, fennel, and squash to sell to the city’s greengrocers.

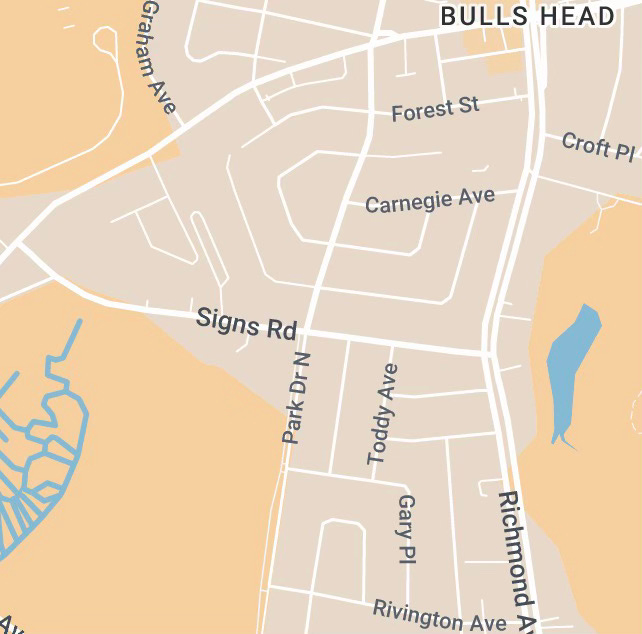

Today, the neighborhood—flanked by the Staten Island Expressway on the north, Willowbrook Park on the east, the Staten Island Industrial Park to the west, and Travis Avenue to the south—is filled with block after block of Cape Cods, High Ranches, and split-level homes. Practically every house has a garage, and many of them have pools.

TAVERN

At the heart of Bulls Head lies the intersection of Richmond Avenue and Victory Boulevard, once home to the neighborhood’s namesake: the Bull’s Head Tavern. Not to be confused with the establishment of the same name on the Bowery (where General George Washington famously stopped for a celebratory pint on his way into Manhattan for Evacuation Day), Staten Island’s Bull’s Head was built in 1741 and became the de facto headquarters for the island’s Tories during the Revolutionary War.

Before the tavern was built, the area was known as “London Bridge,” though nobody seems to know why. The area’s only bridge at the time, a modest footbridge spanning a local stream, bore little resemblance to the storied Thames crossing.

While it wasn’t the only tavern in town, the Bull’s Head had the most memorable signage: a large wooden placard suspended between two posts and painted by a local artist who, according to legend, “exhausted all his talents and resources in transmitting to posterity the picture of a very fierce-looking bull’s head, with very short horns and very round eyes, which looked very much like a pair of spectacles.”

Before, during, and after the war, the Bull’s Head was a favorite haunt for drinkers and gamblers alike. The only thing that dampened the spirits of it patrons was talk of a shadowy figure who “everybody desired to avoid, but who would not be avoided.” We all know the type.

The mystery man was said to have a dark complexion, fiery eyes, and—though no one had actually seen them—hooves and a tail. He’d hang around, follow along as the bargoers stumbled home, then vanish, which, to be honest, sounds more annoying than scary. Occasionally, it was said he would take the form of a black dog the size of a horse which actually does sound a little scary.

SIGNS

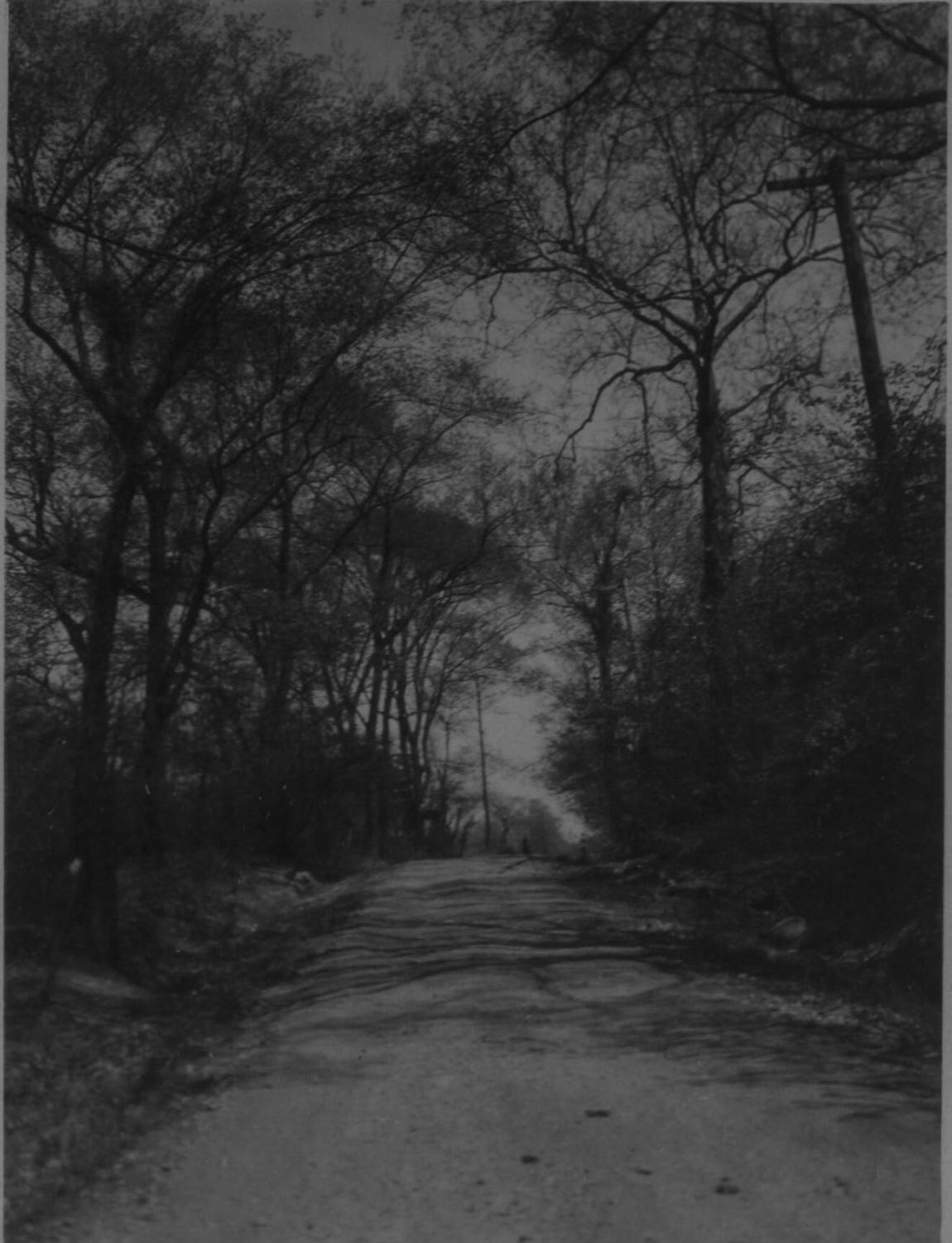

You might chalk up these ghost stories to excessive consumption of the libations on offer at the Bull’s Head, but similar sightings were also reported all along Old Neck Road, one of the area’s original byways. More muddy lane than road, it formed the last leg of the Staten Island portion of the New York–Philadelphia stagecoach route, connecting the ferry at Port Richmond to the New Blazing Star Ferry in Travis.

Reports of an enormous black dog, similar to the one who harassed the Bull’s Head patrons, darting in and out of the woods along the road became so frequent that the stretch was eventually renamed Signs Road, a nod to the many supernatural “signs” seen along its path.

Years later, stories of the boogeyman Cropsey, who lived in the Willowbrook woods, would abound. While there ended up being a real-life Cropsey—serial killer Andre Rand—one has to wonder if stories of the phantom that roamed those same woods were the original inspiration for the legend.

“Many believed this strange apparition haunted the marshes of the Willowbrook and had been seen lurking around nearby taverns, sometimes peering into the windows of local houses. Because of this superstition, few dared venture through the ravine after dark, and only the bravest would walk that road after sunset.”1

In any case, the frequent ghost sightings seem to have eventually taken their toll. Patrons became wary of venturing out after dark, and at least one local tavern shut down entirely.

Then, in the 1820s, all three of the drinking establishments clustered at the Richmond Road intersection burned to the ground. The area was rebuilt and rechristened as Phoenixville. But when the Bull’s Head reopened, the old name returned.

Some version of the bar stood on that corner all the way through the 1960s before later becoming Bagel Nosh and then, most recently, a Dental practice.

ICHABOD

Fittingly, for a neighborhood steeped in the supernatural, Bulls Head is the final resting place of the man who was, in all likelihood, the namesake for Ichabod Crane—the skittish schoolmaster from Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

The “exceedingly lank” Crane “with his whole frame most loosely hung together” had a reputation for cowardice and an eye for local heiress Katrina Van Tassel, whose good looks were only eclipsed by the size of her inheritance. When Katrina rebuffed Ichabod’s proposal in favor of the town meathead, Abraham “Brom Bones” Van Brunt, the dejected schoolmaster mounted his horse, Gunpowder, to take his leave.

Along the way, he encounters the Headless Horseman, riding a black horse and carrying his severed head (later determined to be a pumpkin), which he hurls at the hapless, terrified schoolmaster, who is never heard from again.

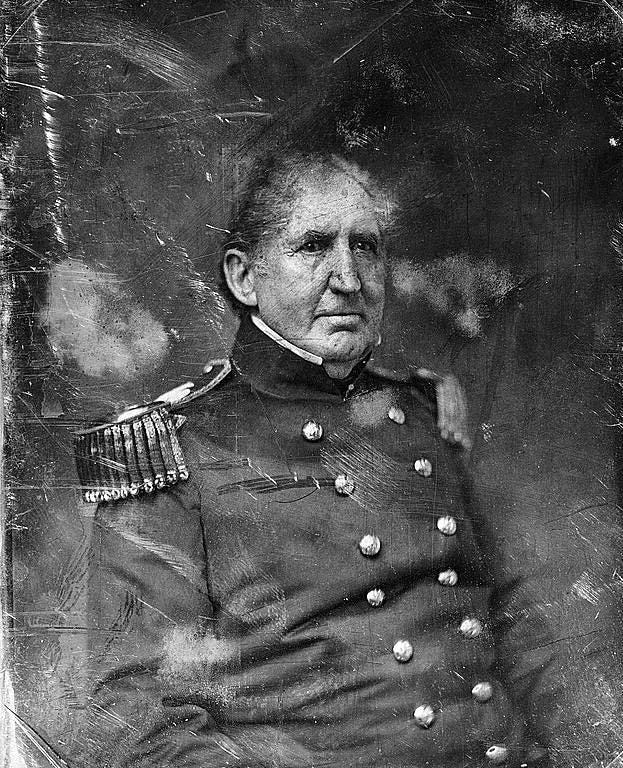

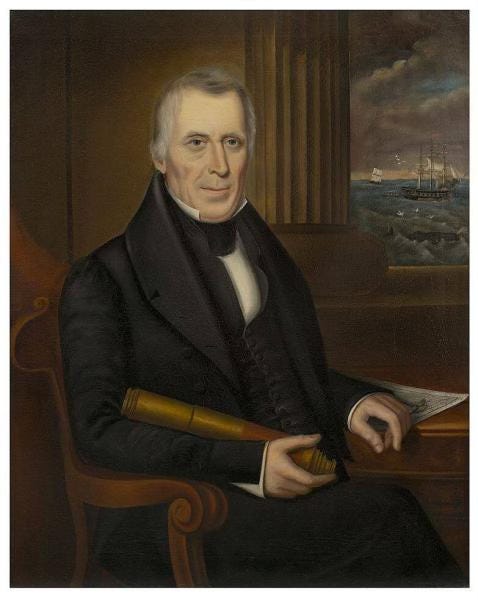

The real-life Ichabod Crane was a colonel who served in the military for 45 years and was probably not too thrilled to be affiliated with the pusillanimous protagonist of Irving’s tale.

In 1814, while working as an aide-de-camp to New York Governor Daniel D. Tompkins (of Tompkinsville fame), Irving visited Fort Pike in Sackets Harbor, New York. At the time, Crane was overseeing the fort’s defenses. While there’s no record of the two men ever meeting, it would be quite a coincidence if Irving just conjured that name out of thin air.

The name Ichabod is Hebrew in origin and means “no glory” or “inglorious,” which might explain why you don’t meet too many Ichabods these days. He joins a long list of memorably named Irving characters, including Preserved Fish, Habakkuk Nutter, Zerubbabel Fisk, and, who could forget, Determined Cock.

Colonel Ichabod Crane died in 1857, and is buried in a rather nondescript corner of what is now the Asbury Methodist Cemetery.

His wife Charlotte, son William, and Juan, “An Indian Boy of the Umpqua Tribe,” who was Crane’s personal valet, are buried alongside him.

Besides the Ichabod Crane monument, the cemetery is filled with numerous graves bearing the names of Staten Island's founding families. Names like Decker, Winant, Egbert, Simonson, and Mesereau that show up again and again in land patents, property records, and historical accounts. Many descendants of these families still live in the borough.

My favorite gravestones, though, are the ones that are so weathered that their inscriptions have been reduced to a kind of incomprehensible braille, an anonymous testament to a life long forgotten.

FOG

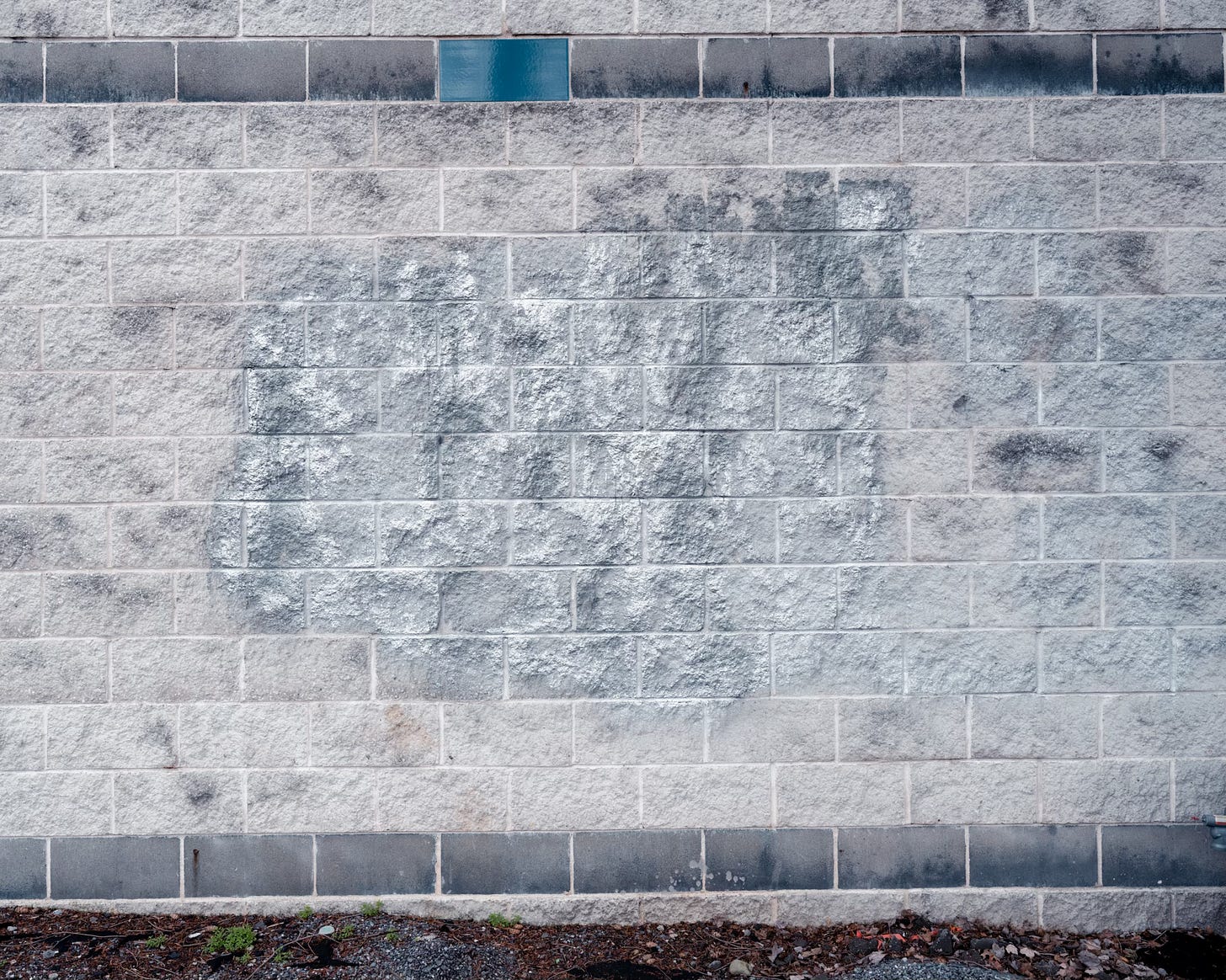

I usually find largely residential neighborhoods like Bulls Head challenging to cover, but there are always pockets of strange and interesting things happening along the edges. That's how I ended up in the Asbury Cemetery. That’s also why I found myself in the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge—the oldest wildlife preserve in New York. The park’s 260 acres contain salt meadows, rock outcropings, and a swamp forest. The refuge is a favorite spot for migrating birds, and over 117 different species have been spotted there.

The refuge was also once a favorite spot to dispose of bodies. Bonanno captain Thomas Pitera, better known as Tommy Karate, thought the swampy soil at the park’s eastern edge (the Bulls Head side) would speed the decomposition process and buried at least six bodies there in the 1990s.

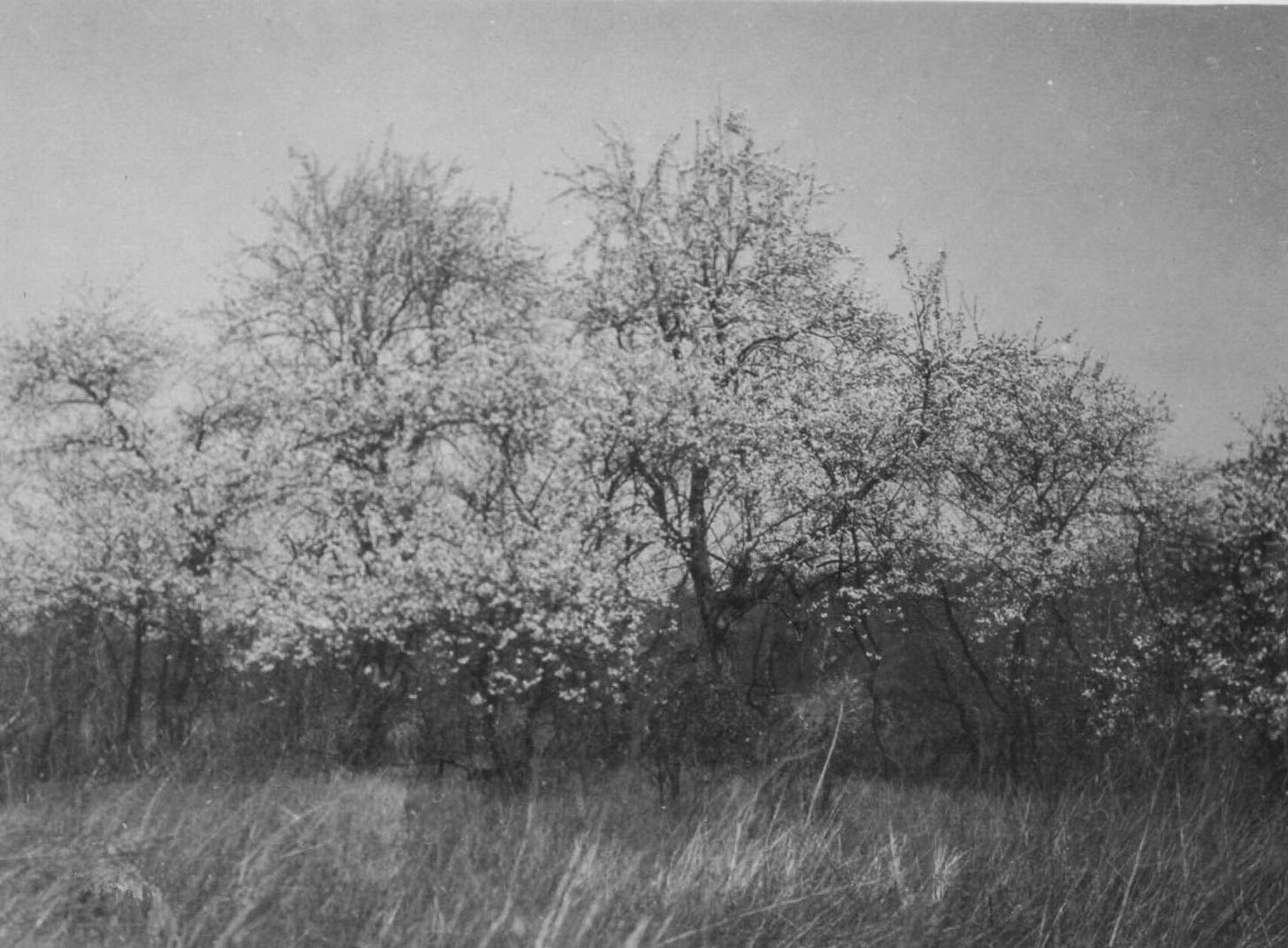

When I visited last week, the woods were beginning to emerge from their winter hibernation. Forsythia was starting to bloom, and the forest’s numerous creeks and small springs were overflowing from the recent rain.

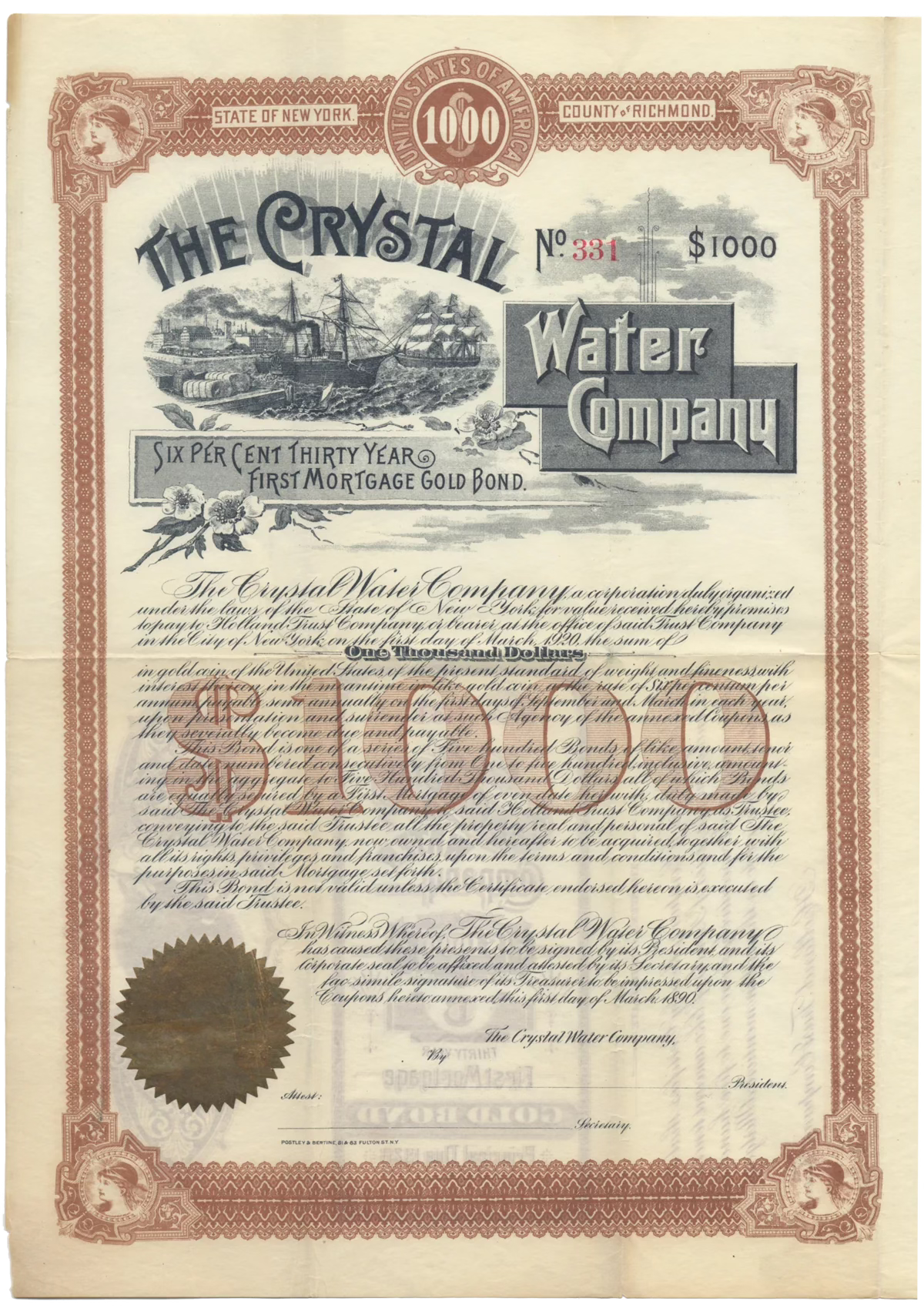

For decades, the Crystal Water Company bottled and sold water from those same springs, though it has been many years (and many dismembered bodies) since the water was actually potable.

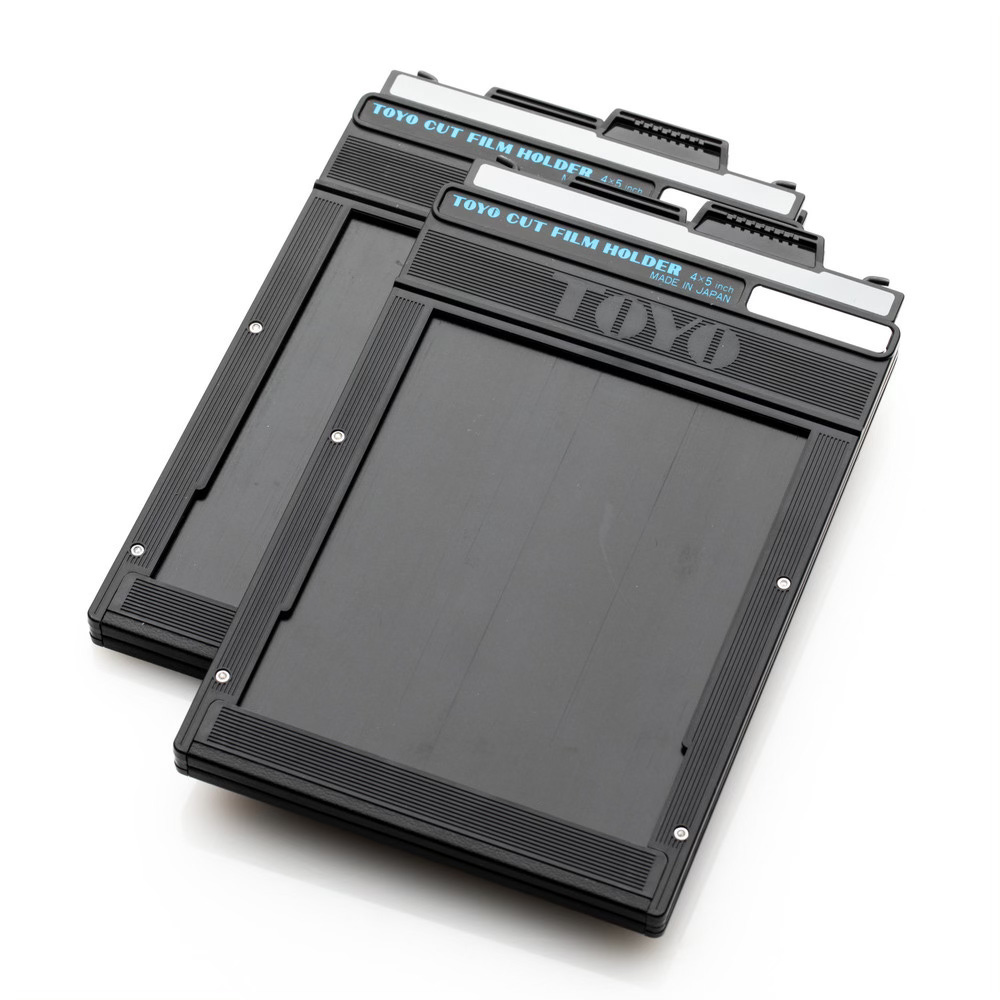

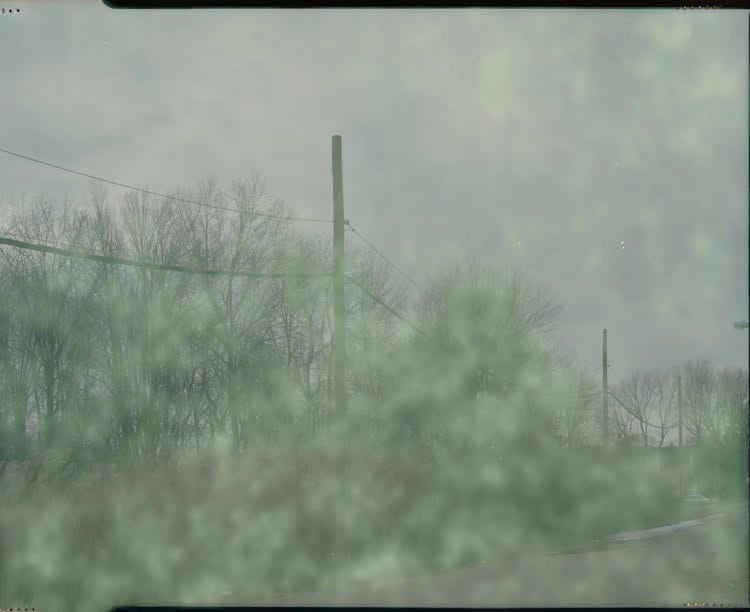

After a few minutes of wandering around the woods, I realized I’d been there years before, though all I had to show for it was a stack of fogged negatives. Before starting this project, I was mostly shooting with 4x5 and 8x10 large format cameras. Most of my 4x5 holders were bought secondhand, so I decided to splurge on a few new ones. At the time, the Japanese-made Toyo holders were considered top-of-the-line—beautifully engineered, with a satisfying heft and dark slides that slid in like butter.

After about a month’s worth of shooting—which, back then, meant maybe 30 pictures—I sent the film out for development. When the negatives came back, I was crushed to find that nearly half of them were ruined by a strange fogging.

I first ruled out the lab, then the camera, and finally chalked it up to a bad batch of film. But when the next round came back with the same issue, I started to panic.

Then, buried deep in the bowels of an internet forum, I found what would later become my support group: a cadre of equally flummoxed photographers all suffering from the same fogging affliction. It didn’t take long to pinpoint the common denominator—a recent acquisition of the supposed crème de la crème of filmholders. Somebody had figured out that the dark slides on the new Toyos weren’t entirely opaque. Using a film holder that lets in light is a little like deploying a parachute made out of kleenex.

Toyo sent me a replacement batch. They had the same issue.

That was the moment I started to warm up to the idea of shooting digital.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

For this week’s audio recording, I stuck to the woods, capturing some gurgling water, and a chorus of Northern Flickers, Black-capped Chickadees, Tufted Titmice, and a particularly garrulous cluster of Red-winged Blackbirds.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Another batch of images from Staten Island’s very own Percy Loomis Sperr. These photos ( courtesy of the New York Public Library) were all taken on or in the vicinity of Signs Road.

ODDS AND END

Sackets Harbor, Long Island, where Washington Irving met Ichabod Crane, was recently in the headlines. Last week, a mother and her three children—aged 9, 15, and 18—were released without explanation after spending more than a week in a Texas detention center. The family, who has an asylum case pending in immigration court, was arrested during a raid on a dairy farm that was aimed at detaining a different person.

1,000 people (in a town of 1,400) turned out to protest their arrests. So-called “border czar” Tom Homan, the mastermind behind these types of raids, lives in Sackets Harbor, and the farm where the raid took place has a giant “Make Milk Great Again” billboard in front of its barns. It is estimated that dairies employing immigrant laborers contribute to nearly 79% of the U.S. milk supply.2

Like Ichabod Crane, Preserved Fish, one of Washington Iriving’s characters was a real person.

Earlier this year, the Sakai Machine & Tools Inc., who had been manufacturing Toyo cameras since 1946, stopped production. Despite my issues with their leaky film holders, I still love by Toyo 810M even though it weighs more than a small horse.

.

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b24209fda02bc5bf5953ca1/t/65c26589d07a9820c476b99a/1707238808675/SIHistorian_July-Sept1962.pdf

https://www.dairyherd.com/news/business/impact-immigration-reform-u-s-dairy-farms#:~:text=Recent%20reports%20highlight%20this%20dependency,of%20the%20U.S.%20milk%20supply.

"...a black dog the size of a horse..." I have a fictional dog who might be able to fight that...

I'm a fan of Irving's work, so knowing of some of the facts behind "Sleepy Hollow" is great. I would say, given the Hebrew origins of his name, Ichabod Crane had the moniker he deserved.

Neat stuff, as usual. Have you been to Broad Channel?