Tompkinsville, in the northeast corner of Staten Island, is one of the borough’s closest points to Manhattan and, consequently, among its earliest settlements. The neighborhood’s history predates Giovanni da Verrazzano’s visit in 1524. Over the centuries, it has served as an anchorage for British warships during the American Revolution, the site of violent quarantine protests in the 19th century, and, in 2014, a catalyst for the Black Lives Matter movement following Eric Garner’s death.

THE WATERING PLACE

Though Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage is often considered the de facto begining of European exploration of New York Bay, Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed into the harbor nearly 85 years earlier. The bridge that bears his name makes landfall on Staten Island about two and a half miles south of where the local Lenape tribe once guided Verrazzano to anchor his ship in 1524. The site was just offshore from a natural spring known as The Watering Place, later incorporated into the town of Tompkinsville.

They came toward us very cheerfully, making great shouts of admiration, showing us where we might come to land most safely with our boat.

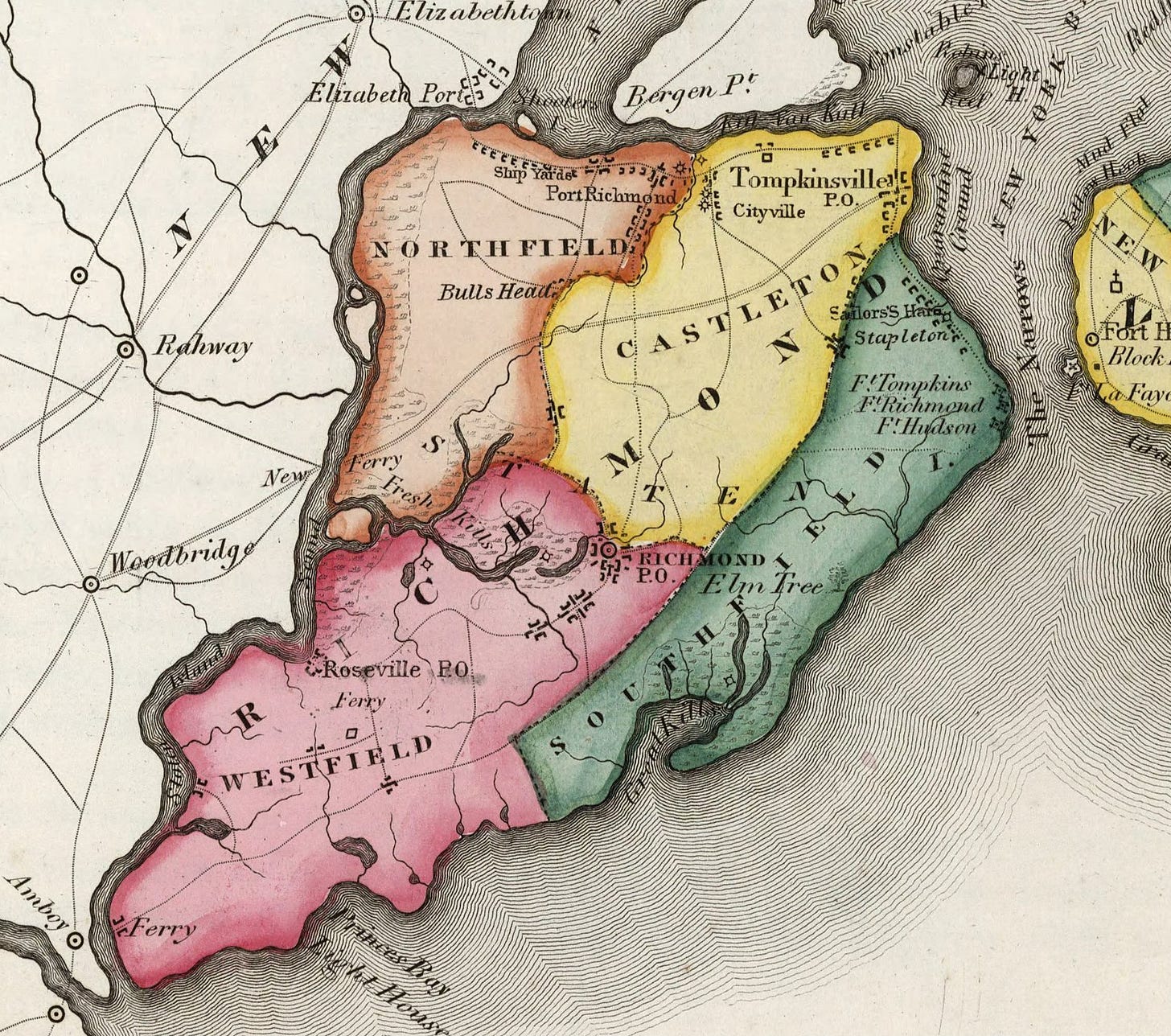

Following Hudson’s visit, small groups of Dutch, French, and English settlers began to arrive on Staten Island. By the late 17th century, roughly 200 European families had settled there. With them came diseases and guns, spurring the remaining Lenape to sell their land. Richmond County was officially established in 1683 and later divided into four towns: Northfield, Southfield, Westfield, and—bucking the geographic naming trend—Castleton.

The 5,100 acres of Castleton, officially known as The Manor of Cassiltowne, belonged to Governor Dongan, the 2nd Earl of Limerick, who had recently been appointed Governor of New York. In 1678 Dongan was called back to England and he left the estate to his nephews.

One hundred years later, the anchorage at the tip of Castleton, where Verrazzano had once overnighted, served as a staging ground for British warships at the height of the Revolutionary War.

On July 2nd, 1776, General Howe anchored 130 ships, with 9,000 soldiers offshore from the Watering Place. A week later, 150 more ships arrived under the command of General Howe's brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe.

Two more fleets joined, and soon, the anchorage was teeming with redcoats and the occasional blue-coated Hessian mercenary. There were frequent skirmishes between rebel troops who tried to cut off access to the freshwater the British forces depended on to supply their ships.

In August 1776, a giant flotilla left The Watering Place and headed towards Brooklyn. Three hours later, 15,000 British and Hessian soldiers landed on the shores of Gravesend Bay.

This neat but somewhat creepy animation, made by the West Point Department of History, does a good job of depicting the massive operation.

DANIEL D. TOMPKINS

Tompkinsville gets its name from Daniel D. Tompkins, who founded the settlement in 1815 while serving as the fourth Governor of New York State. Tompkins built a dock along the neighborhood’s waterfront and began offering daily ferry service between Staten Island and Manhattan, the precursor to the Staten Island Ferry. He also constructed the Richmond Turnpike, which connected the town of Travis (née Linoleumville) to Tompkinsville. The turnpike linked the New Blazing Star Ferry, originating in New Jersey, with his newly built Tompkinsville ferry line, creating a continuous passage between Philadelphia and Manhattan.

After World War I, Richmond Turnpike was renamed Victory Boulevard, a main artery in Staten Island. Beginning in 1816, Tompkins served two terms as Vice President under James Monroe. He died in Tompkinsville just three months after leaving office at the age of 50.

QUARANTINE WARS

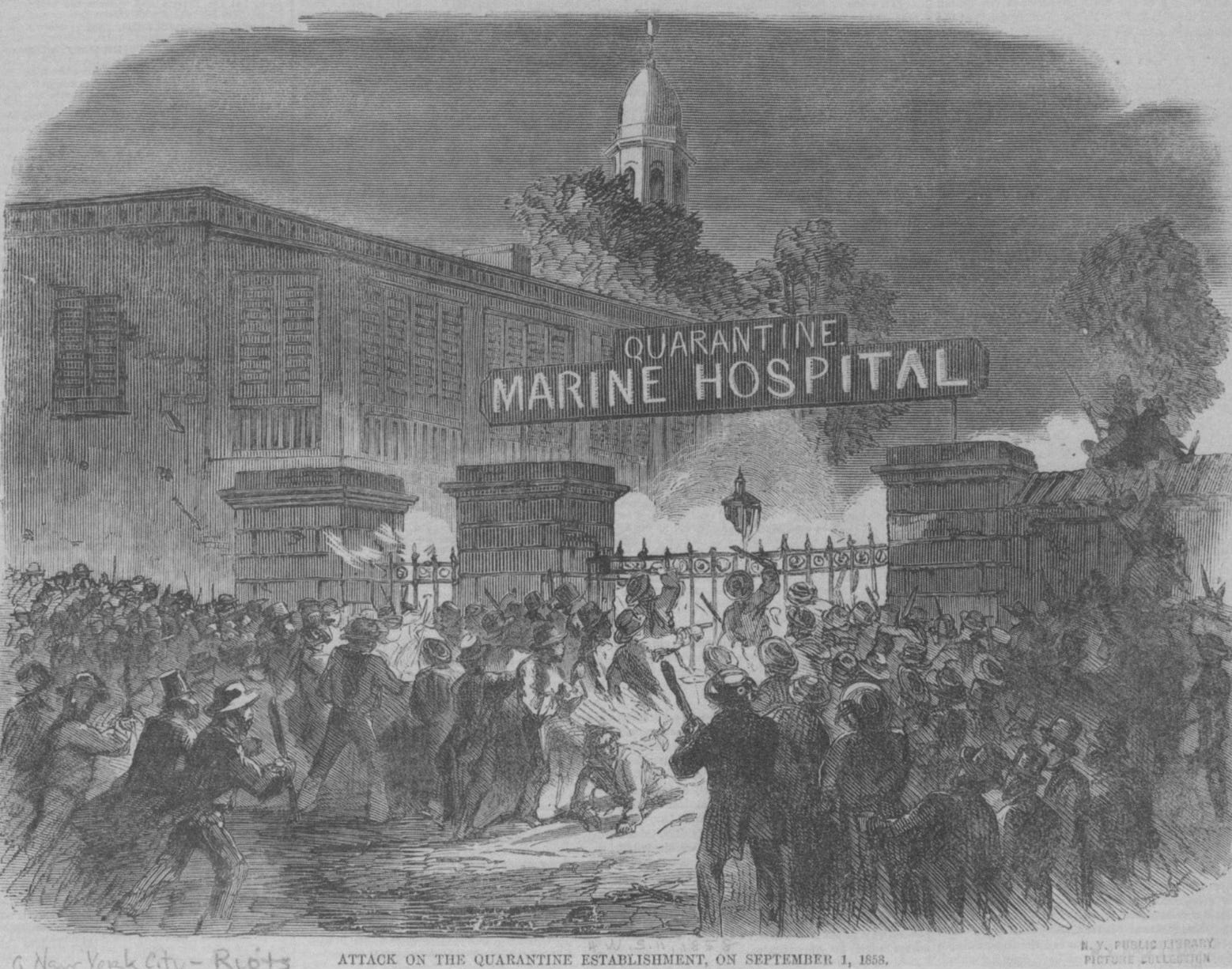

By the end of the 18th century, New York City had been ravaged by a series of yellow fever outbreaks, prompting the passage of the 1799 quarantine laws and the construction of the New York Marine Hospital, colloquially known as The Quarantine. Situated on the border of what would become Tompkinsville and St. George, the 11-building, 30-acre complex was built on land seized by the state through eminent domain. The facility could house over 1,000 patients, or roughly a quarter of the entire population of Staten Island at the time of its construction. Predictably, the whole seizing land to build an infectious disease shelter for immigrants gambit didn’t go over well with the locals, especially after several outbreaks of yellow fever, or “black vomit,” swept through the area.

Benjamin Dawson, a Manhattanite who built his summer house 600 feet northwest of the Quarantine, described the situation:

“We can look into the windows and hear the cries of the patients …. The smell that seems to proceed from putrid flesh is horrid …. The stench was smelt every day in the hot months, about the time the burial trench was opened, and it caused great nausea and sickness at the stomach.”

On one hand, that doesn't sound very good. On the other hand, if you wittingly build your summer getaway within spitting distance of an infectious disease facility…

On September 1, 1858, after repeated appeals to the state legislature yielded no results, the Castleton Board of Health passed a resolution declaring the hospital “a pest and a nuisance of the most odious character, bringing death and desolation to the very doors of the people.” That same evening, a mob of prominent locals—including a Justice of the Peace and Ray Tompkins, grandson of Daniel D. Tompkins—stormed the Quarantine, armed with makeshift battering rams, bales of hay soaked in camphor, and plenty of matches. They set the hospital ablaze, burning it to the ground.

Patients were dragged from their beds and placed outside as the hospital burned around them.

A fire engine company arrived, led by the aptly named Thomas Burns, a vocal opponent of the Quarantine and the owner of Nautilus Hall, a saloon and hotel across the street. After breaking down the main gate, Burns and his crew stood by, claiming their hoses had been cut, as the rest of the mob poured in.

After gathering at Nautilus Hall to celebrate their accomplishments the following evening, the group returned to the site and torched the few remaining buildings.

The incident prompted widespread condemnation from outlets like The New York Times, which deemed it “the most diabolical and savage procedure that has ever been perpetrated in any community professing to be governed by Christian influences… for pure senseless ruffianism it is without a parallel.”1

Ringleaders “Honest” John C. Thompson and Ray Tompkins were arrested and tried for arson. However, their lawyer argued that arson, by definition, required setting fire to an occupied house. Since the Quarantine was not a house and its occupants had been removed before the fire, the charges were invalid. He further claimed the destruction was an act of self-defense. The presiding judge, Henry B. Metcalfe, who owned property near the hospital and had previously argued for its closure, agreed and the men were acquitted.

In the years that followed, a new quarantine station opened in the Staten Island neighborhood of Rosebank, while sick passengers were diverted to Hoffman and Swinburne Islands—artificial landforms built specifically to prevent the fate of their predecessor.

If you want to learn more about the Quarantine Wars, I highly recommend Kathryn Stephenson’s (no relation) 2004 paper.

ERIC GARNER

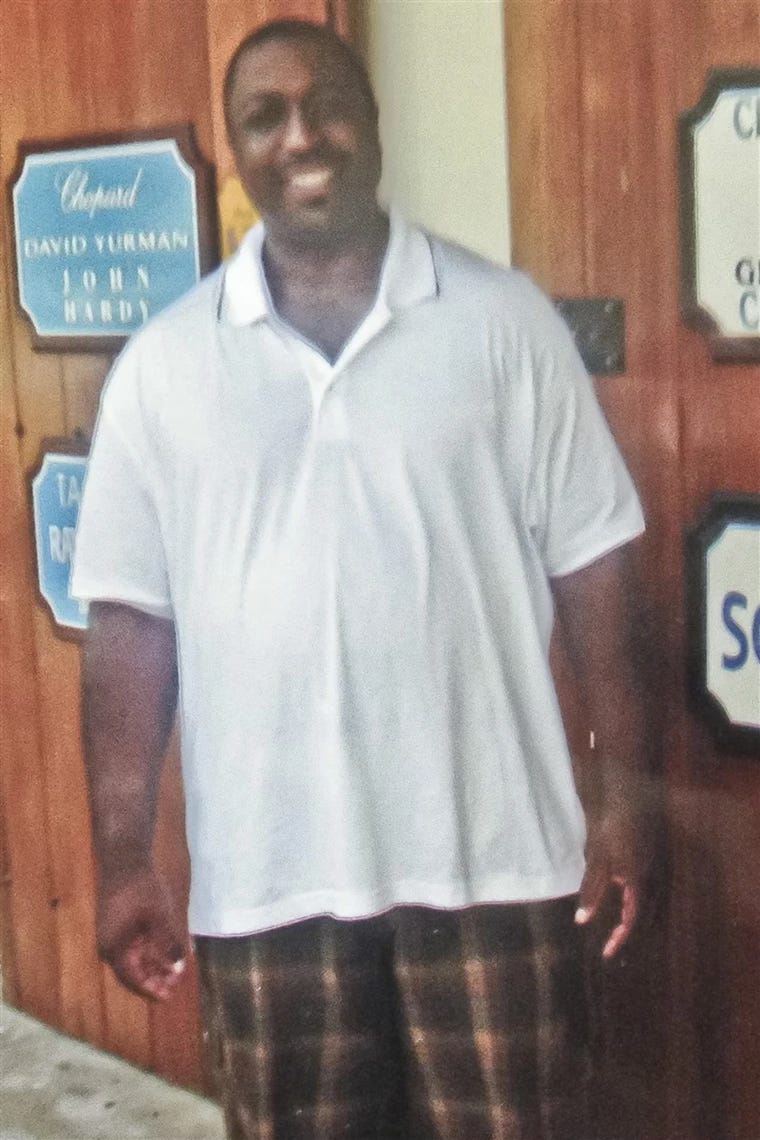

After nearly a century of relative calm, Tompkinsville returned to the headlines in 2014 with the tragic death of Eric Garner, who died after being placed in a chokehold by an NYPD officer.

The incident began when police approached Garner to arrest him for allegedly selling loose cigarettes outside a beauty supply store on Bay Street. When Officer Daniel Pantaleo and several other officers attempted to detain him, Garner pulled his arms away, saying, “Don’t touch me, please.” Pantaleo then placed him in a chokehold, bringing him to the ground. Garner repeated the words “I can’t breathe” 11 times while lying face down on the sidewalk before losing consciousness. He suffered a fatal heart attack on the way to the hospital.

Garner’s death sparked widespread condemnation of the NYPD’s use of excessive force, and his final words became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement.

After a Richmond County grand jury declined to indict Pantaleo, the Department of Justice launched its own investigation, but Attorney General William Barr ultimately decided not to press federal charges. Pantaleo remained on the force until August 19, 2019, when the NYPD dismissed him following an internal trial.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s soundscape features some deep tuned chimes, a sermon delivered from the loudspeakers outside a taqueria, and some kids at recess.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

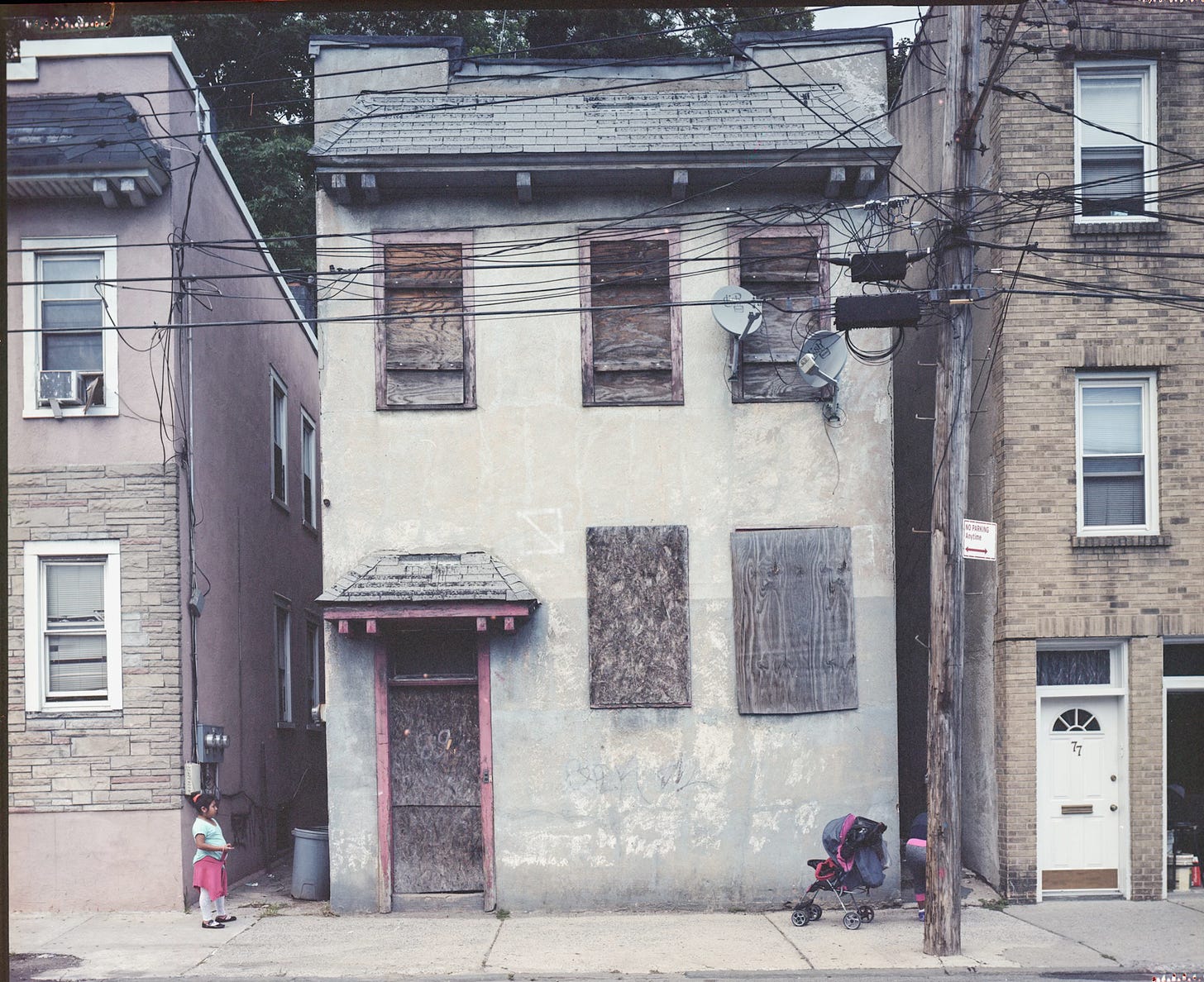

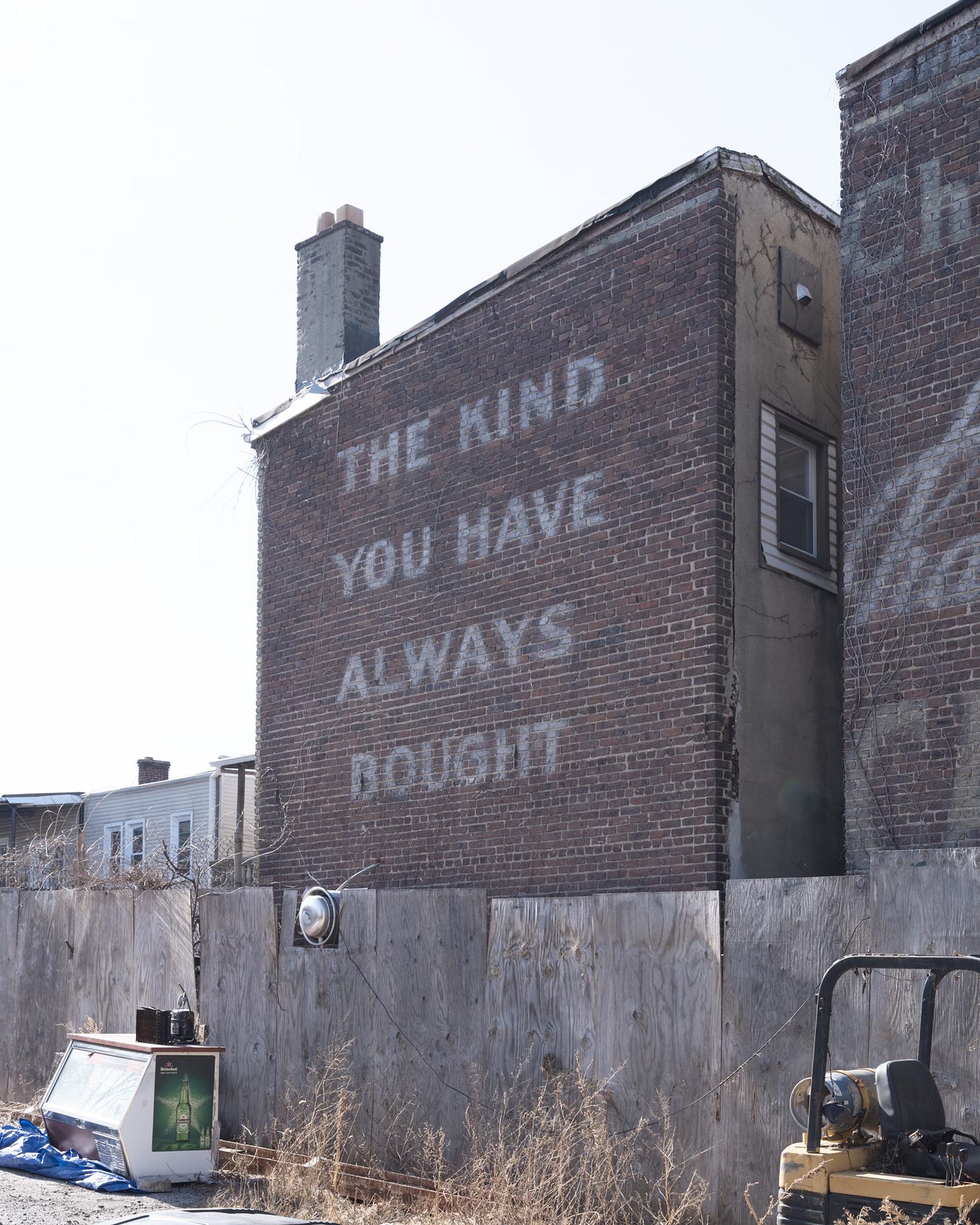

South African filmmaker and photographer Gareth Smit moved to NYC to study at the International Center for Photography in 2014, the same year Eric Garner was killed.

Smit spent several months in Tompkinsville earning the trust of Garner’s friends and relatives while documenting the aftermath of his death.

Mr. Smit’s photographs tell two stories. One captures the ordinary lives of black Staten Island residents in the kind of images that are often overshadowed by the popular perception of the borough as overwhelmingly white. The other involves the varied ways that the people who live in the neighborhood mourn . Some march. Some sing. Some look after the plastic box that marks the spot where he was wrestled to the ground.

Here are some photographs from that project:

You can see more of Smit’s work on his website

ODDS AND END

Until 2018, the Verrazzano Bridge was spelled with only one “z,” making it the second New York City bridge with a missing consonant, as I wrote about in the Throggs Neck newsletter

Staten Island is home to over 5,000 people of Sri Lankan descent, the largest concentration in the U.S. While Lakruwana in nearby Stapleton remains the go-to spot for a sit-down feast, New Asha, in the heart of Tompkinsville’s Little Sri Lanka, is consistently praised for serving some of the best Sri Lankan food in the city.

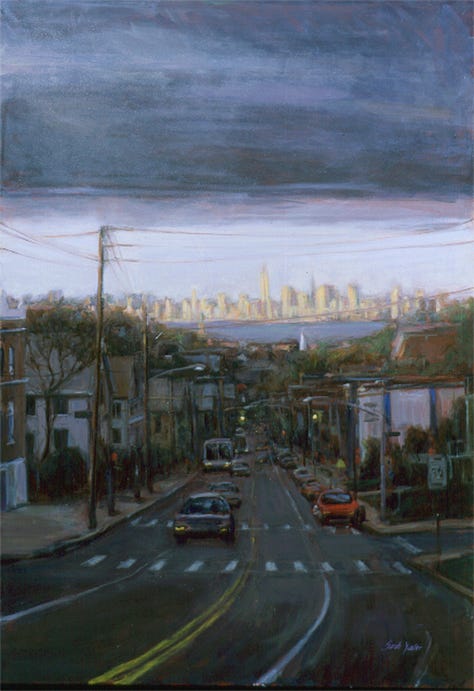

Artist and Staten Island resident Sarah Yuster made a series of paintings showing the view of Manhattan down Victory Boulevard.

https://nyti.ms/4ioPldS

“the most diabolical and savage procedure that has ever been perpetrated in any community professing to be governed by Christian influences… for pure senseless ruffianism it is without a parallel.”

I honestly think that today's journalists should study these old papers so that their work can become as engaging to readers now as it was to readers then.

The denizens of the Quarantine may have said "I can't breathe" as many times as Eric Garner each day of their confinement, but their deaths were long and agonizing, whereas his was quick, tragic and possibly preventable.

What an obscure End sign at the end. You have to peer to catch it. What fun, like a Where’s Waldo game!