Woodlawn - The Bronx

Sandhogs and Spicebags: A look into the Tunnels, Tombs, and Pubs of Little Ireland.

Woodlawn Heights, often referred to simply as Woodlawn, sits at the northern edge of the Bronx. This small triangular neighborhood is bordered by the Bronx River Parkway to the east, Van Cortlandt Park to the west, Woodlawn Cemetery to the south, and Yonkers to the north.

The neighborhood takes its name from the adjacent cemetery. Unlike nearby Norwood, a significant portion of the neighborhood’s Irish population, many of whom arrived in the early 1840s to dig the Old Croton Aqueduct, has remained in the area, earning it the nickname Little Ireland.

Woodlawn’s main commercial strip, Katonah Avenue, runs just eight blocks but boasts at least as many pubs, with names like The Burren, The Lark’s Nest Pub, and Behan’s Public House. Nearby McLean Avenue, technically in Yonkers but often considered part of Woodlawn, has even more.

It’s not uncommon to hear an Irish brogue on the sidewalk, especially in summer, when hundreds of J-1 exchange students (“J-1ers”) arrive from Ireland looking for jobs and a bit of familiarity. A recent U.S. Census Bureau study found that 45% of Woodlawn’s 7,500 residents claim Irish ancestry, down from 60% in 2000. The neighborhood’s shifting demographics are embodied by the half-Irish-Chinese, half-Mexican menu at The Kitchen, a “mini-embassy of curry chips and nostalgia,” where you can pick up a burrito or a spicebag, or, if you can’t decide, a spicebag burrito.

WASHINGTONVILLE

In the 18th century, this part of the Bronx was known as Washingtonville, named for General George Washington, who built a fort in the southeast corner of what is now Woodlawn Cemetery during the Revolutionary War. After the war, the area between the Bronx and the Hudson River was mostly farmland and woodlots. Things began to change after the New York and Harlem Railroad, designed by John Stephenson (no relation), was constructed along the Bronx River. Once a stop was added, the area became an ideal site for a much-needed cemetery.

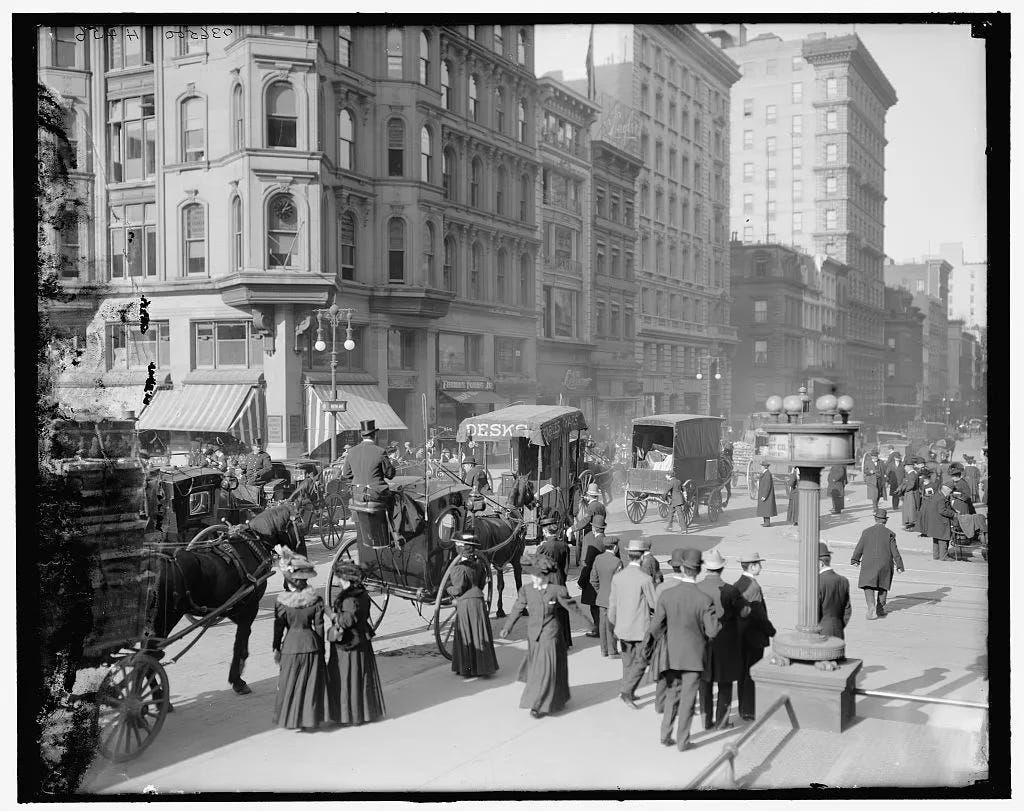

At the time, Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery was the city’s primary burial ground, but funeral processions routinely got stuck in traffic on 42nd Street, then the city’s northern edge, en route to the ferries to Brooklyn. Though the automobile was still 20 years away, the gridlock was already legendary. With no traffic lights or police officers, and fetid mounds of steaming manure blocking large swaths of the road, the streets were in constant chaos.

Horse-drawn vehicles of every description, from overburdened drays to cabs and private carriages, filled them wheel-to-wheel. In the absence of horns, shouting was the approved way of pushing one's way through, and crossing an intersection was a matter of the survival of the boldest.1

In 1863, Reverend Absalom Peters, a theologian and poet, assembled 12 trustees and purchased 313 acres to establish a rural cemetery they named Wood-Lawn. By train, the journey from Grand Central to the cemetery took less than 35 minutes. The first interment, Phoebe E. Underhill, was made in January 1865.

Today, Woodlawn Cemetery contains over 320,000 burials and is the final resting place of a veritable who’s who of New York and American culture.

In 1873, George Opdyke—likely the same George Opdyke who served as mayor of New York from 1862 to 1864—purchased land adjacent to the railroad and began to develop it, naming the neighborhood after the cemetery.

The first residents were primarily Irish and Italian laborers who had worked on the cemetery and later on the Old Croton Aqueduct, which runs beneath Van Cortlandt Park. The completion of the IRT subway line in 1917, connecting Woodlawn to the rest of the city, sparked a flurry of residential development, mostly one and two-family homes that still define the neighborhood’s architecture today.

SANDHOGS

It makes sense that the headquarters of the local tunnel workers’ union is based in Woodlawn, considering that so many of the neighborhood’s early settlers were involved in digging the Croton Aqueduct. The facade of the Local 147 union building on Katonah Avenue resembles the dark, gaping maw of one of the hundreds of miles of tunnels its members have excavated beneath the city.

Officially, the union represents the Compressed Air and Free Air Workers, Shafts, Tunnels, Foundations, Caissons, Subway, Sewer, and Cofferdam Construction Workers of New York, New Jersey, and Adjacent States and Vicinity, but everyone just calls them sandhogs.

For more than 150 years, sandhogs have labored in the bowels of New York, digging down while the city builds up. Their work began with projects like the Croton Aqueduct in the 1840s, but it was their efforts digging in the sandy soil at the bottom of the East River to build footings for the Brooklyn Bridge that earned them their name.

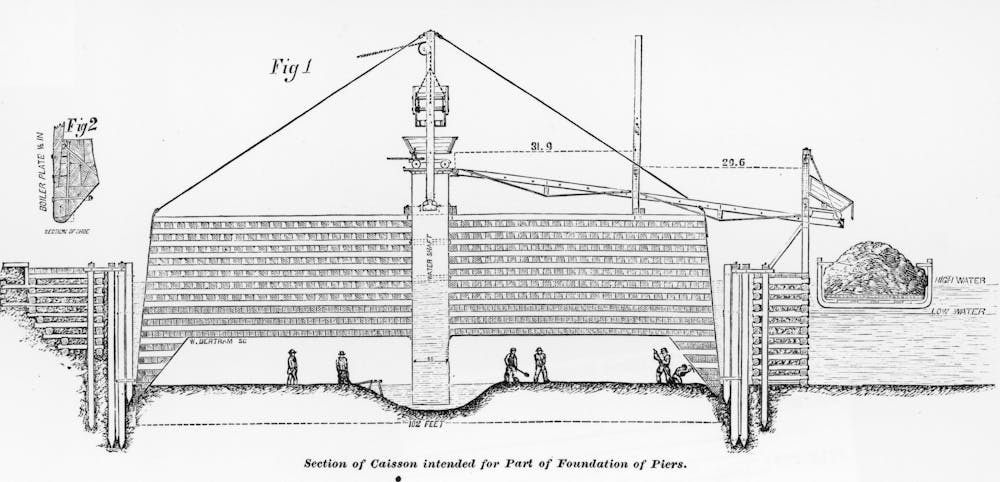

Workers dug the bridge’s foundations in caissons, large wooden boxes filled with compressed air to keep water and silt out. The chambers were cramped, boiling hot, and poorly lit. The possibility that the pressurized air would leak out and river water would rush in was very real.

Many of the workers (including the bridge's chief engineer, Washington Roebling) suffered from the bends, a decompression sickness that caused paralysis, extreme pain, and even death when workers ascended too quickly. Over 20 men died during the bridge's construction, most of them from the bends.

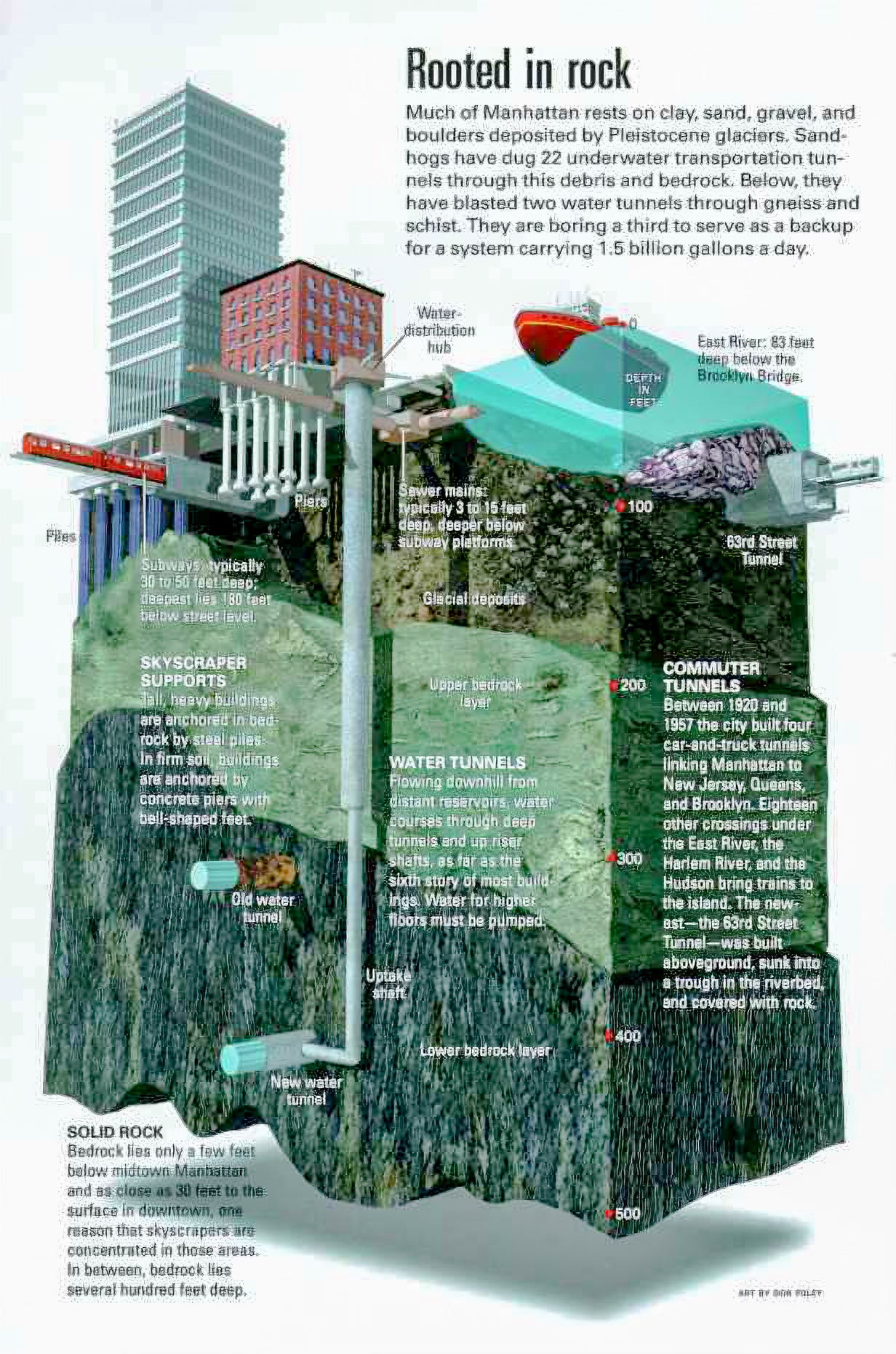

Since then, sandhogs have built the Holland, Lincoln, Battery, and Midtown Tunnels, all of the city’s subway tunnels, its sewer systems, its water tunnels, and 105 miles of steam tunnels that heat and power landmarks like Grand Central Terminal, the Empire State Building, and the United Nations.

Not surprisingly, creating massive tunnels hundreds of feet underground that require large amounts of explosives is a dangerous job. Besides the bends, sandhogs have died from cave-ins, blowouts, electrocutions, falls, and silicosis, a lung disease caused by inhaling fine silica dust generated during excavation.

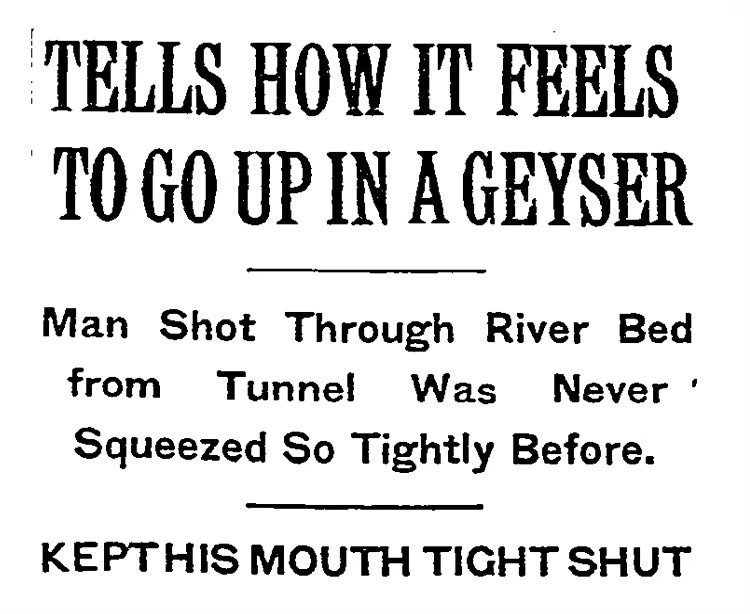

One of the most infamous stories in sandhog lore involves Marshall Mabey, a 28-year-old sandhog who, in 1916, noticed a rupture in the wall of the tunnel he was working on under the East River near Brooklyn Heights. Within seconds, Marshall and two others were sucked into the hole, propelled through 12 feet of river mud, pushed through the water and finally ejected from the river surface atop a 25-foot geyser. While his coworkers died, Mabey was released from the hospital days later and returned to work the following week.

The longest project the sandhogs have ever worked on is the still unfinished Water Tunnel No. 3, the largest capital construction project in city history.

Begun in 1970, Water Tunnel No. 3 stretches 60 miles and burrows up to 500 feet below the surface. It was designed to allow the older water tunnels (built in 1917 and 1936) to finally be shut down and inspected. The job has taken so long that the sons of the original sandhogs now work alongside their fathers.

Because sandhogging is often a multi-generational occupation, Woodlawn has remained the de facto sandhog capital. Besides the union headquarters, there is a memorial on the edge of Van Cortlandt Park with 23 manhole covers honoring the 23 men who lost their lives between 1970 and 2000 during the construction of City Water Tunnel No. 3.

Today, thanks to improved oversight and advanced technology, like the 450-ton tunnel boring machine known as the mole, deaths are thankfully much rarer.

WOODLAWN CEMETERY

I’ve written a lot about New York’s cemeteries in this newsletter, and on my first visit, I decided to skip Woodlawn, but the more I researched who’s buried there, the more I realized a return visit was in order.

My first stop was Jazz Corner, where Miles Davis' polished black granite gravestone sits within viewing distance of those of Duke Ellington, Illinois Jacquet, Max Roach, and Lionel Hampton.

Ornette Coleman, W.C. Handy (the father of the blues), and Coleman Hawkins are all buried nearby, too. Celia Cruz, "La Guarachera de Cuba," has her own mausoleum, right down the path from The Little Flower, Fiorello La Guardia, New York City's 99th mayor, and often considered its best.

Herman Melville is buried here.

So is Nellie Bly, the pioneering investigative journalist whose undercover reporting from the New York Lunatic Asylum resulted in the book Ten Days in a Mad-House. Her grave was unmarked until the New York Press Club paid for a headstone in 1978.

Her former employer, Joseph Pulitzer, is also buried here, though his grave is a little more ostentatious, featuring a bronze figure sculpted by William Ordway Partridge.

Speaking of ostentatious, the pure white Egyptian Revival Frank Woolworth mausoleum is not what you would expect from a man who pioneered the five-and-dime store, the precursor to today's ubiquitous 99-cent store. Then again, as the New York Sun once wrote, "He won a fortune, not showing how little could be sold for much, but how much could be sold for little.”

The grave I was most curious about belongs to the man who shaped so much of the city in the twentieth century, Robert Moses. Though I was half expecting a massively engineered totem to match the scope of Moses' projects and ego, The Power Broker and his wife, Mary, are buried in a modest (by Woodlawn standards) community mausoleum. Of course, the bridges, highways, and parks (not to mention the means with which they were built) are his true monuments. Two of his projects, the Mosholu Parkway and Deegan Expressway, are within earshot of Moses’ final resting place.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording features the sounds of Muskrat Cove and the nearby Metro-North tracks.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Photographer Richard Barnes has an impressive and varied body of work, ranging from the haunting photographs of Ted Kaczynski’s (also known as the Unabomber) cabin to murmurations of starling flocks in Rome, to the back rooms and diorama displays of natural history museums. In 2012, Barnes, recipient of the Rome Prize and the Alfred Eisenstaedt Award for Photography, was commissioned by The New York Times to document the construction of the Second Avenue Subway tunnel.

The first thing that stuck me as we descended the ninety feet below Second Avenue was the scale of the tunnel excavation rising in some places four to five stories above us,” Barnes told me. “The workers were dwarfed by the monumental scale, especially as the tunnels opened up to where the station platforms will one day be built. Next, I couldn’t get over how much like a movie set it felt. I had brought my own lighting equipment with me, as I was expecting it to be extremely dark down there. Instead, I was surprised (and I guess I shouldn’t have been, as workers need to see) by the amount of light in the pit. Jules Verne, Stanley Kubrick, Frank Herbert, and David Lynch’s all but forgettable "Dune" were some of the literary and cinematographic references the site conjured up for me. I strove to bring this quality of otherworldliness to my images, as it was kind of unbelievable that this magical world exists now below the surface of the Upper East Side of Manhattan.”2

All photographs copyright Richard Barnes.

For more of Richard’s work, check out his website

NOTES

In his fantastic 1998 novel This Side of Brightness, Colum McCann tells the story of Nathan Walker, a sandhog whose story was inspired by Marshall Mabey’s trip through the East River.

In 1895, Nellie Bly married millionaire industrialist Robert Seaman, who was 73 to her 31 years. When her husband died, she took over his Iron Clad Manufacturing Company, which produced steel containers, such as milk cans and boilers. During her time at the helm, she invented a new milk can and a stacking garbage can. Though she is not listed on the patent, she is also often credited with the invention of the 55-gallon oil drum, which would make her, tangentially at least, responsible for the only major acoustic musical instrument invented in the 20th century.

Here is a great podcast courtesy of 99% Invisible featuring interviews with several Sandhogs.

For a more modern take on Marshall Mabey’s unplanned geyser ride, you can do no better than the 1995 cinematic masterpiece, Die Hard with a Vengeance.

Story of Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY." Interment.net, n.d., www.interment.net/data/us/ny/bronx/woodlawn/story-of-woodlawn-cemetery-bronx-ny.pdf.

https://www.newyorker.com/galleries/gallery-seeing-the-subway

Probably my favorite NYC neighborhood outside of Staten Island. Nice and quiet, relatively suburban, but has that direct rail connection to Manhattan that County Richmond doesn't have (and likely never will). And if I ever wanted to go out on a bender without driving my car, Woodlawn would be the perfect place!

I am frequently guilty of making personal comments here Rob, but how can I help it when you include the pub where we had both our 25th and 50th high school reunions? Also my great grandfather, Max Simson, a New York character in his own right ( Google Max Simson goes Jail, Lottery, NY Times) is buried in Woodlawn.