Earlier this week, while walking around Norwood in the Bronx, I saw an older man burst out of a building in shorts and a t-shirt, a cigarette dangling from his lips. As I got closer, he caught my eye and waved me over.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

I started my usual spiel explaining this project, but he cut me off, visibly frustrated. “But why?” he pressed. “Why a photographer? Why not an astronaut? Or a janitor? Why?”

I told him I wasn’t smart enough to be an astronaut and too messy to be a janitor. This seemed to satisfy him, prompting a monologue about the joys of looking and discovery. Then, suddenly, he stopped, looked me in the eye, and said with complete seriousness, “I just want to say one thing.” He paused. “Happy Monday.”

Then, with the North Bronx variation of a bro hug, he sent me on my way.

I had been feeling a little uninspired that morning so this small gesture was just the thing I needed. Newly invigorated, I set off to explore the neighborhood that was once a key Revolutionary War site, a vital source of fresh water for the Bronx, and a refuge for immigrants fleeing The Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Today, Norwood is home to a working-class community where the Irish have been largely replaced by immigrants from Latin America, Albania, Bangladesh, Russia, and Korea—what The New York Times calls “a miniature U.N. bordered by parkland.”1

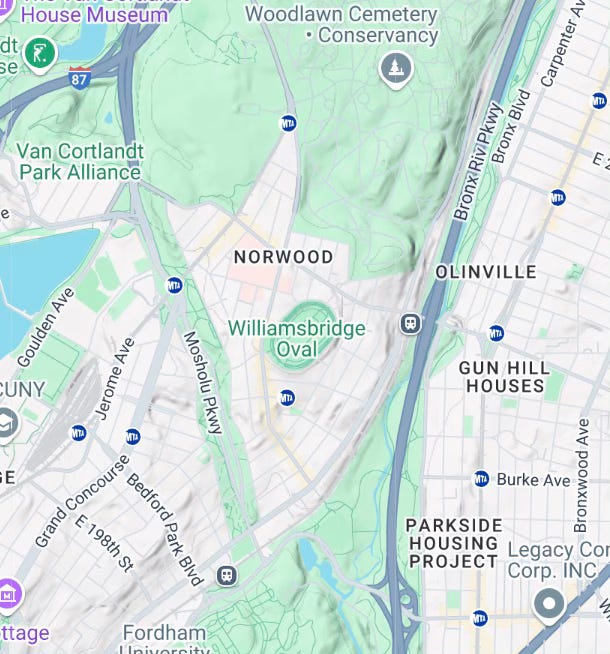

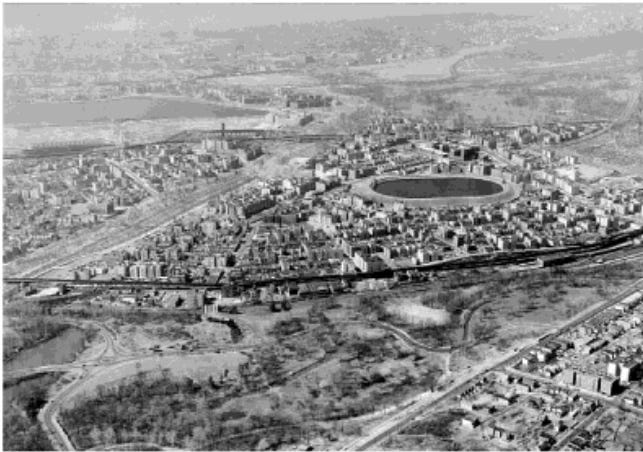

Norwood is the only neighborhood I’ve covered that is entirely surrounded by green space, with Van Cortlandt Park and Woodlawn Cemetery to the north, the Bronx River to the east, and Mosholu Parkway to the southwest. At its center sits the sunken Williamsbridge Oval lending the triangular neighborhood a quasi volcanic countenance.

Norwood’s largest landowner and employer is Montefiore Medical Center, which has anchored the community since 1913. In 1981, the hospital founded the Mosholu Preservation Corporation, buying and renovating several apartment buildings to keep rents affordable, helping Norwood avoid the worst of the crime and disinvestment that ravaged the South Bronx.

NORTH WOODS

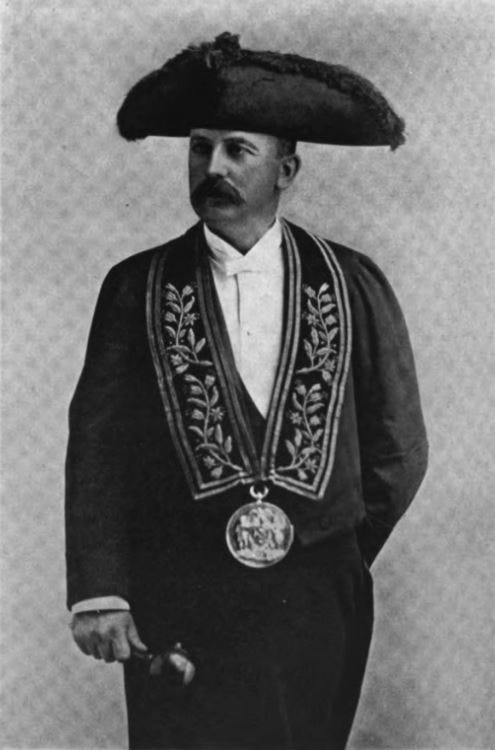

Most sources attribute the name Norwood to a portmanteau of North and Woods, though a small contingent claims the neighborhood was named after Carlisle Norwood, a friend of Leonard Jerome who built the nearby Jerome Racetrack. Norwood's son, Carlisle Jr., was the 28th president of the Saint Nicholas Society, a role which required him to wear this ridiculous hat

Back when the area was mostly wooded, Norwood was the site of several Revolutionary War battles, and many of its local streets pay homage to international war heroes like Rochambeau, DeKalb, and Steuben.

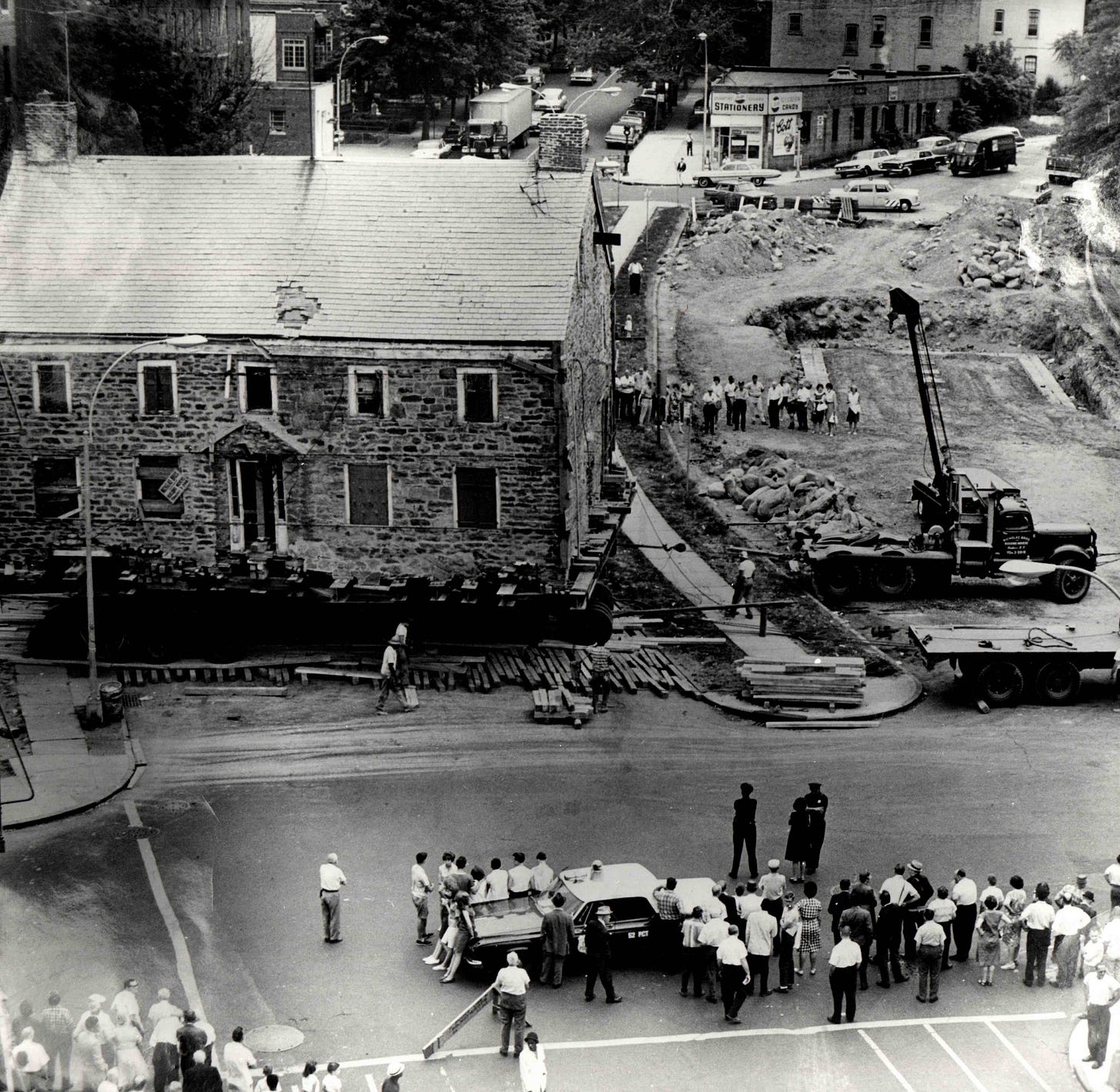

The Valentine-Varian House on Bainbridge Avenue is a vestige of those days and is the second-oldest building in The Bronx. The house was occupied by a succession of Isaacs—the first being Isaac Valentine, a blacksmith and farmer who built the fieldstone house in 1758.

At the height of the Revolutionary War, the building was briefly occupied by British Colonel Robert Rogers until he and his troops were driven out by General William Heath. Eventually, Isaac Valentine sold the house to Isaac Varian, a butcher and dairy farmer, whose grandson, Isaac Varian IV, would go on to become the 63rd mayor of New York City.

The Varians sold the house in 1905, though this time, no Isaacs were involved. In 1965, the house was donated to the Bronx Historical Society that turned it into the Museum of Bronx History, but not before lifting it up and moving it across the street.

LITTLE BELFAST

In the 1980s and 1990s, Norwood became informally known as “Little Belfast,” when waves of undocumented immigrants fleeing The Troubles of Norther Ireland, joined an already established Irish community in the neighborhood. At its peak, no fewer than 18 pubs were concentrated along the main drag of Bainbridge Avenue and 204th Street with names like The Green Isle, The Derby and McDwyers

In 1989, Thomas Maguire, owner of one of those pubs, The Phoenix, was accused of plotting to buy 2,900 explosive detonators to ship to the IRA. Prosecutors alleged that Maguire made two cash withdrawals totaling $14,000 from accounts tied to his tavern to purchase the detonators. His lawyer, however, argued that the money was for bar renovations, and the judge agreed, acquitting Maguire and five other men accused of being in on the plot.

The US recession in the 90s, and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, led many of Norwood’s Irish residents to move back to Ireland. Today you’d be hard pressed to find a pint of Guinness in Norwood—the neighborhood’s last Irish pub, McDwyers, closed down in 2017.

OVAL

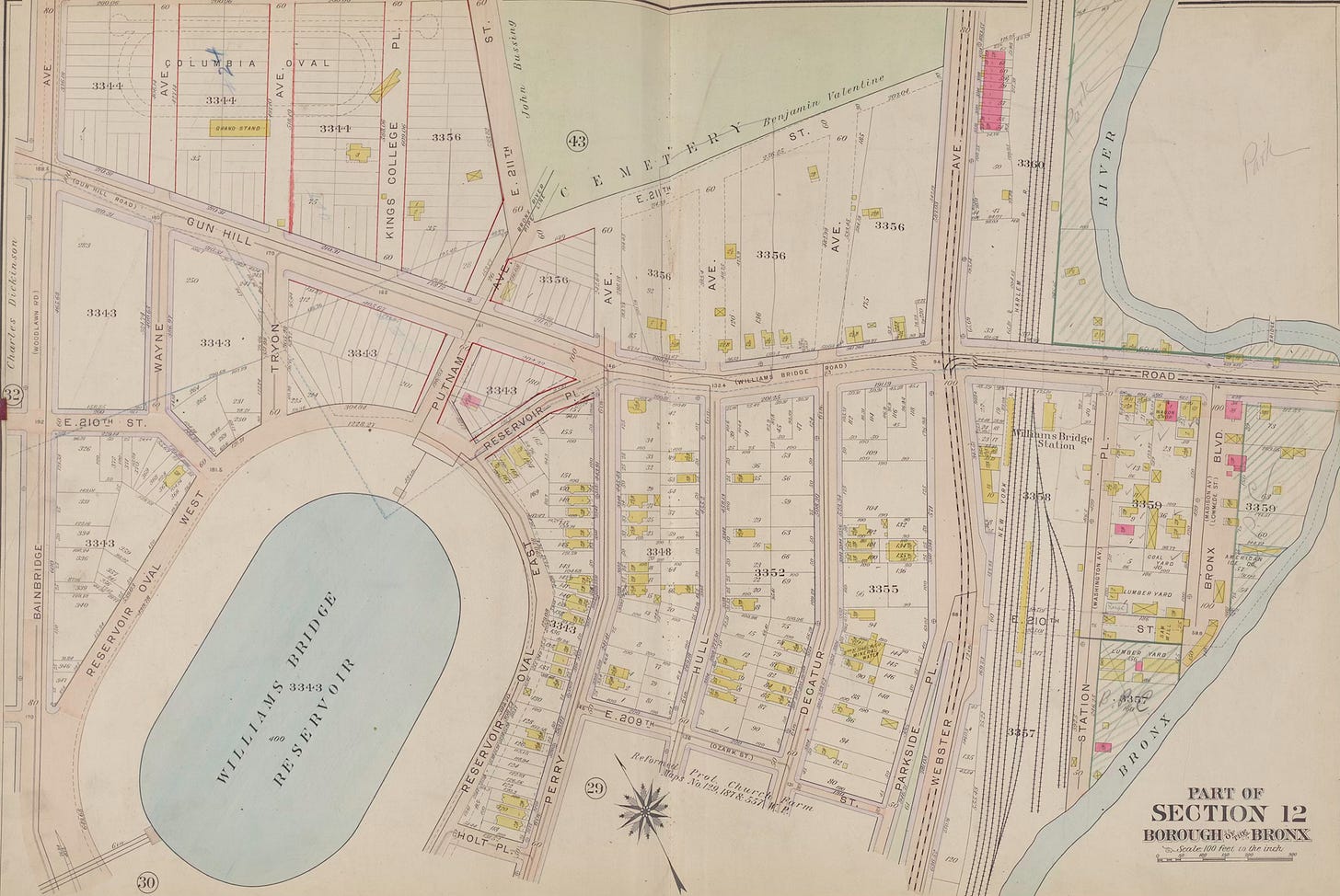

At the center of Norwood is its most recognizable feature, the Williamsbridge Oval, a sunken 20-acre park with a racetrack, football fields, basketball courts, and skate parks. In the late 19th century, as the Croton Aqueduct reached capacity and the growing Bronx needed more water, the city converted a lake in the middle of the neighborhood into the Williamsbridge Reservoir, fed by the Bronx and Byram Rivers water system.

When the nearby Jerome Park Reservoir—part of the New Croton Aqueduct system—was completed in 1906, the Williamsbridge Reservoir became superfluous. Between 1919 and 1925, the reservoir served as what was billed as a “community swimming hole.” Aerial photos reveal a rather sinister looking black void, more like a portal to the underworld than a spot for a summer dip.

Eventually, Robert Moses got his grubby little mitts on the former reservoir and proposed converting the inner slopes of the oval into seating for 100,000 spectators overlooking dual amphitheaters (because one amphitheater is never enough) and swimming pools. Cooler heads prevailed, and thanks to WPA funding, a more modest plan was implemented—resulting in the Williamsbridge Oval Park that exists today.

These photos from the 1930s show the park under construction.

CALVIN AND RALPH

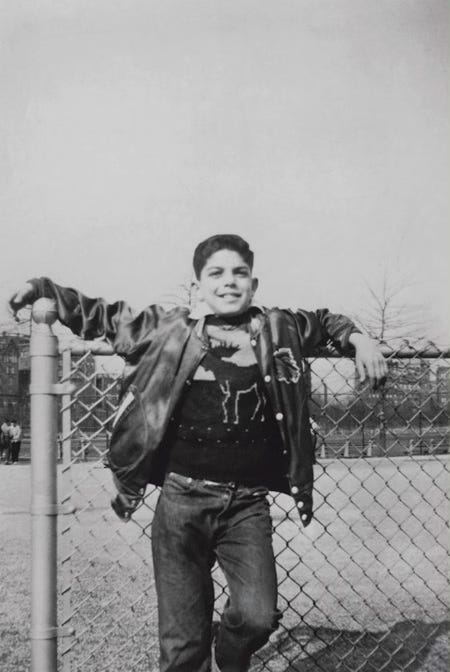

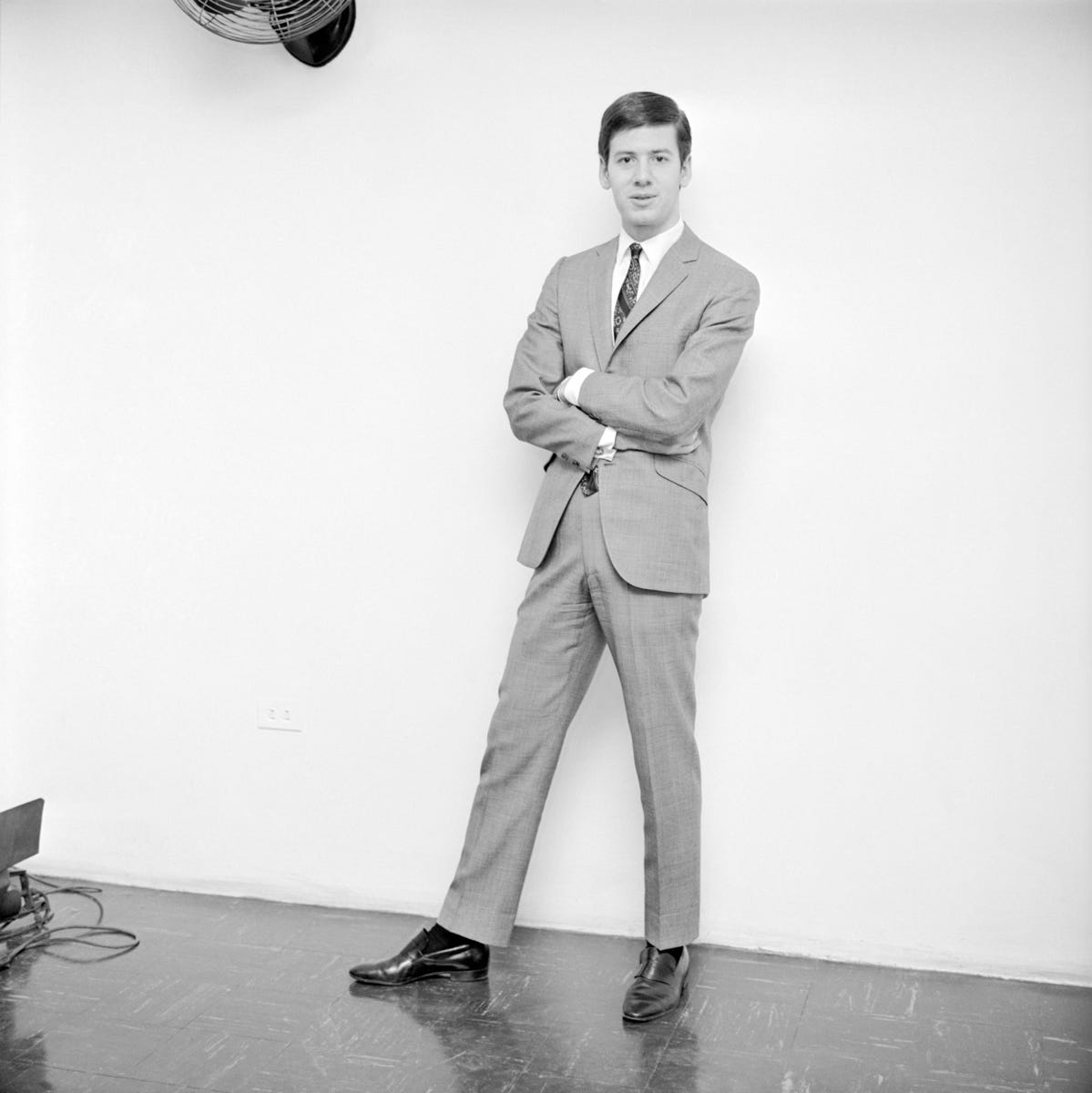

You wouldn’t expect a small Bronx neighborhood whose biggest claim to fame was a drained oval to be an incubator of modern fashion, but improbably, two of the biggest names in the industry—Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein—both grew up in Norwood.

The two designers were born within three years of each other, Lauren in 1939 and Klein in 1942, both to parents who had immigrated from Eastern Europe. The Kleins lived in an apartment at 3191 Rochambeau Avenue, while the Laurens (née Lifshitz) lived in an apartment on Kossuth Avenue overlooking the parkway.

A New York Times article from 2009, which explored the coincidence of the two fashion icons growing up just a few blocks from each other in the 1940s, attributed their success not to the neighborhood itself but to its proximity to other places.

Barry Lewis, an architectural historian, suggested that it was the Bronx’s closeness to the WASP epicenters of Westchester and Connecticut that shaped and influenced the two designers. Meanwhile, Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy at NYU, attributed the coincidence to “a universal Bronx hunger” to escape—one easily satiated by a quick ride on the D train into Manhattan.

Whatever the reason, we can thank these fashion forward men from Norwood for the popped collar trend and massive billboards that make us feel bad about ourselves.

DUCKY BOYS

While Ralph Lauren was busy making his ties wider and Calvin Klein making his underwear tighter, some of their neighborhood contemporaries were getting up to no good as part of one of the Bronx’s most notorious gangs. For such a fearsome horde, they had a ridiculous name: The Ducky Boys. Their preferred hangout was the banks of the Twin Lakes on the northern edge of the New York Botanical Garden, where they huffed glue and honed their slingshot skills—often taking aim at the hapless waterfowl that gave the gang its name.

“Webster Avenue was Ducky Boy country. They roamed their turf like midget dinosaurs, brainless and fearless. They respected only nuns and priests. They would fight anyone and everyone, and they’d never lose. They’d never lose because there were hundreds of them—hundreds of stunted Irish madmen with crucifixes tattooed on their arms and chests, lunatics with that terrifying, slightly cross-eyed stare of the one-dimensional, semihuman urban punk killing machine. And they were nasty—used tire chains, car aerials, and the “Webster Avenue walking stick,” a baseball bat studded with razors.” - Richard Price

Price continually harps on their diminutive size, but that had more to do with their average age than any genetic abnormality—most Duckies were just young teenagers. What they lacked in stature, they made up for in numbers, with over 100 members at their peak. The scene in The Wanderers where the Duckies slowly amass on a Van Cortlandt Park football field—their numbers multiplying until one side is a sea of faded denim and baseball bats—captures the gang’s sheer immensity.

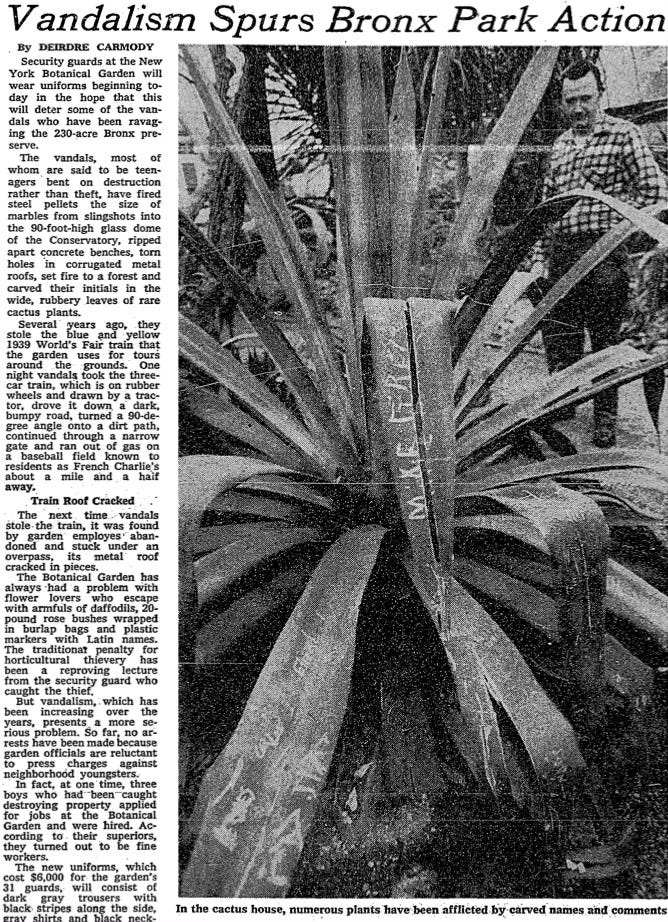

Though stories of their slingshot prowess and razor-studded bats undoubtedly fueled the imagination, in reality, the Ducky Boys (and girls) were mostly just bored kids who figured they had a better chance of not getting beat up if they stuck together. The biggest threat they posed was to the grounds of the New York Botanical Garden, which, for some reason, they really had it in for.

The gang was involved in several incidents including hijacking the garden tram, setting fires, shooting marbles into the 90-foot glass dome of the conservatory and carving their initials into various rare plants. These may not have been the Bloods or the Crips, but if you were a horticulturist, there was no gang more feared than the Duckies.

LOUD TALKING

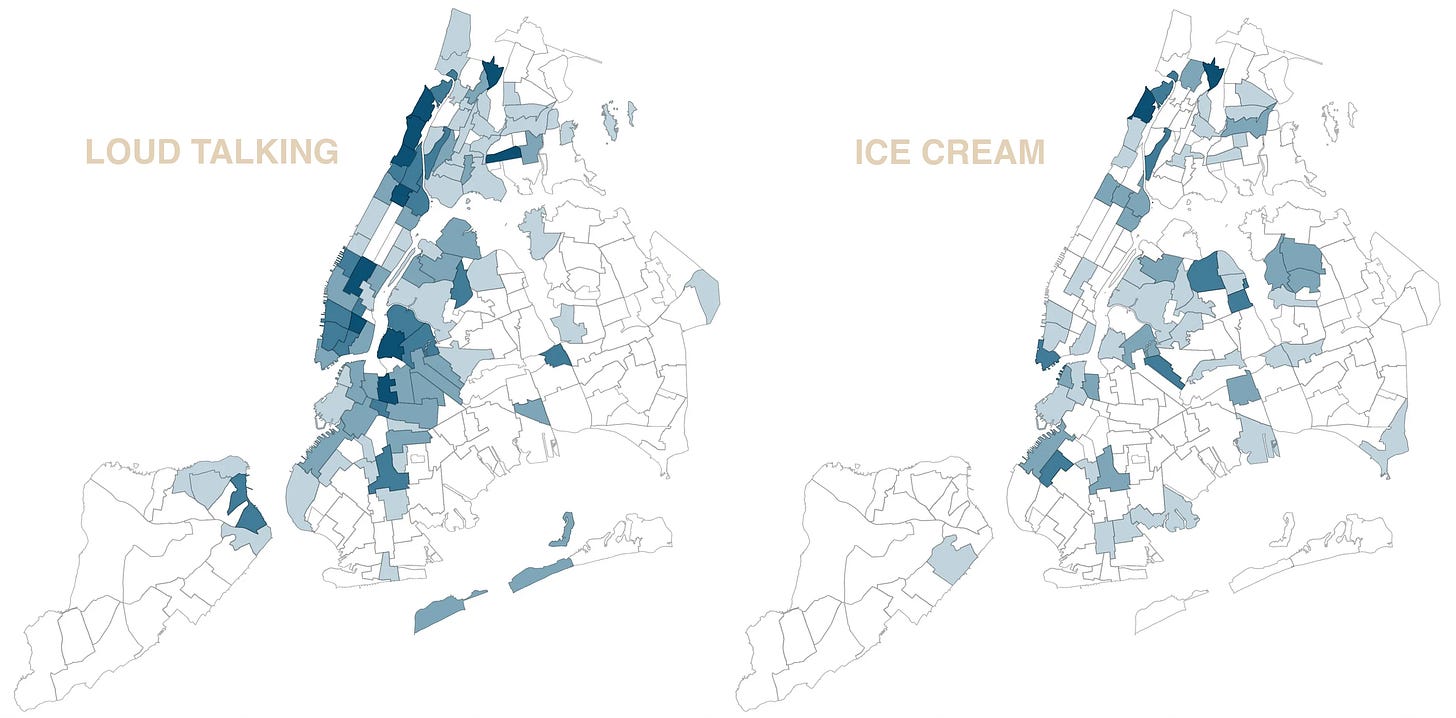

In a 2015 piece for the New Yorker, Ben Wellington, who used to run the I Quant NY blog, analyzed 140,000 311 calls to determine which neighborhoods complain the most about different noises. I was shocked to learn that Norwood leads the city in complaints about “loud talking.”

I’ve walked around plenty of neighborhoods with much louder talking. Heck, on any given night, the inane drunken banter wafting through my windows which overlook the backyard of what is frequently voted Brooklyn’s “Best Dive Bar” is about ten times louder than anything I heard in my walk around Norwood. Of course timing matters, and maybe some of the most egregious loudmouths have moved on since 2015, but I’m guessing there are a few serial 311 callers skewing the numbers here. The neighborhood also ranks near the top in complaints about ice cream truck jingles, further confirming my crotchety complainer theory.

SIGHTS SOUNDS

As much as I was hoping to come across some evidence of loud talking or ice cream trucks, no luck. It’s a pretty mellow soundscape this week.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHERS

The Bronx Historical Society, housed in the Valentine-Varian House in Norwood, is currently hosting an exhibit of photographs by Seis del Sur called Historias: The Stories Behind the Images.

Seis del Sur is a photography collective started by Bronx photographers Joe Conzo, Jr., Ricky Flores, Ángel Franco, David González, Edwin Pagán and Francisco Molina Reyes II. Their site has some pretty strict prohibitions against sharing images, so I’m just going to link to the exhibition here.

ODDS AND END

Learning that MSNBC talking head and newscaster Chris Hayes was a former Norwood resident prompted me to download the audiobook version of his most recent book The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource. The irony of listening to a book about our increasingly fractured and commodified attention spans as a way to avoid the task I had originally set out to accomplish—writing this newsletter—is not lost on me. I’m only about a third of the way through, but so far, so good.

Rob Reiner, aka Marty DiBergi, the director of the greatest rockumentary of all time, This is Spinal Tap, grew up in Norwood.

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley also grew up in Norwood and was a member of the Ducky Boys. This 2018 video features Frehley, and Kiss bassist Gene Simmons putting on a private performance as part of Gene’s $50,000 “Home Vault Experience. The 30 minutes of tuning and Rolling Stones covers rivals anything in Reiner’s mockumentary masterpiece.

Did you know that the classification system that quantifies and categorizes the stages of male-pattern baldness is called the Norwood Scale? Well, now you do.

I’m around a 5, still a few years away from what is more commonly known as the “Power Donut” or “Cul de Sac,” but already at the stage where I actually require sunscreen on the top of my head. I’m not taking it as hard as the guy in the illustration, though.

Norwood has its own newspaper, the Norwood News, which comes out a bi-weekly and also covers nearby Bedford Park, Fordham, and University Heights.

https://www.nytimes.com/1999/09/05/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-of-living-in-norwood-a-miniature-un-bordered-by-parkland.html

Roaming bands of out of control teens is my living nightmare.

"Why not an astronaut? Or a janitor? Why?” - Solid questions- LOL. I am not quite sure from the photo if Carlisle jr.'s hat has 3 corners, but you had an old German children's song popping up when I saw it which literally translated says "My hat, it has three corners,Three corners has my hat.And had it not three corners,It would not be my hat." and equally like the hat itself makes no sense.

I am confused by the 59C or 69C deal ...Everything 1Dollar or more...- nice. As to the Norwood Scale for Boldness...is that because of the donut? Kinda makes more sense than the hat.

Great article again- thanks Rob!