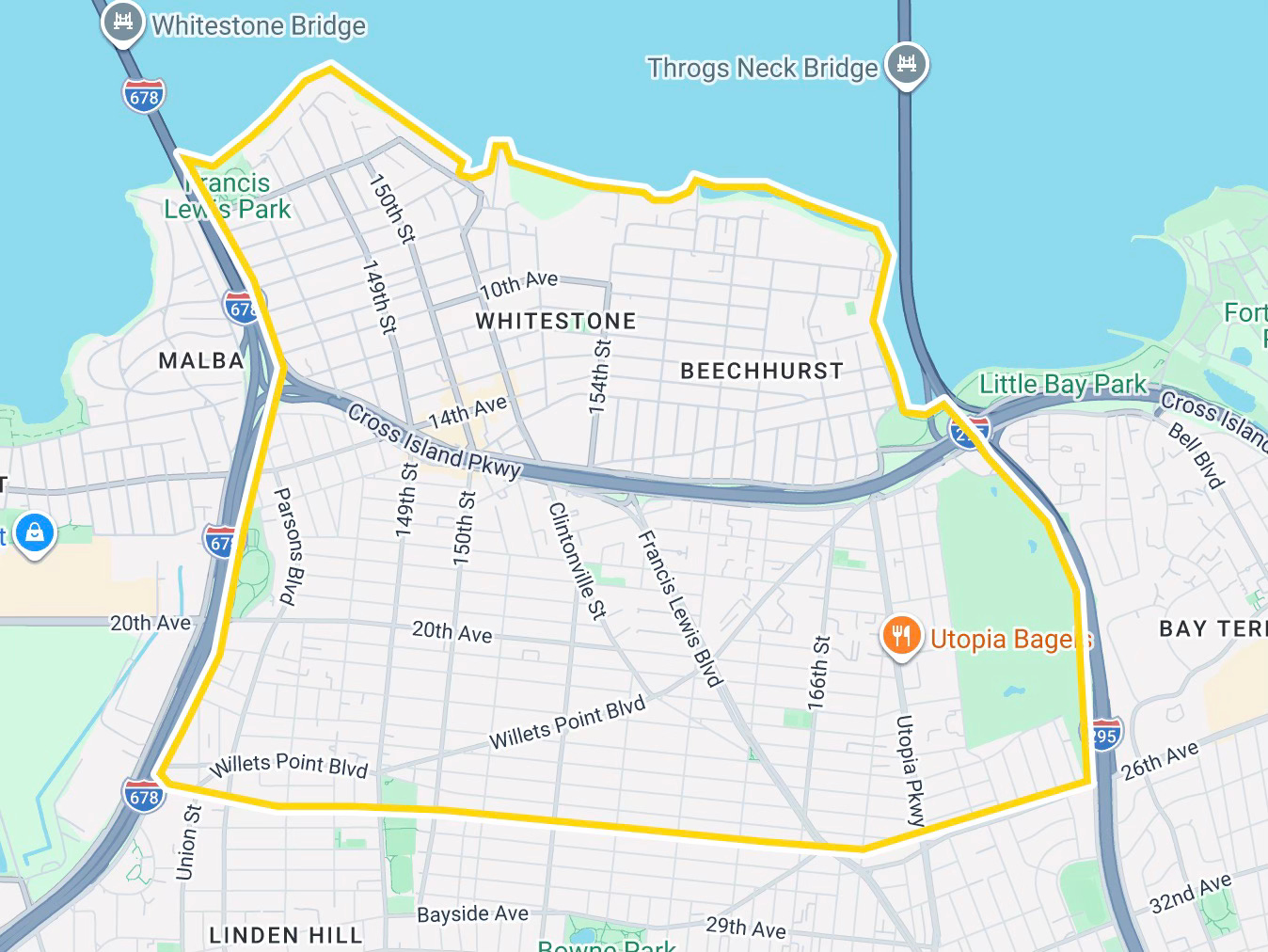

Whitestone - Queens

Two Bridges, Two Delis and Too Much Magic

I kicked off last week’s newsletter with a lengthy preamble about just how bitterly cold it had been, complaining about the city’s treacherous sidewalks and dirty mounds of snow. Of course, it only got colder. Those lined pants I was ready to return? Back on the table. When the “real feel” hits twenty below, all bets are off.

I spent the worst of it inside the cavernous Javits Convention Center, where I watched thousands of teenagers (including my daughter), amped up on venti iced matcha lattes and fistfuls of NERDS Gummy Clusters, whack volleyballs at one another with unmitigated ferocity. I took a full-speed ball directly to the face, and despite the fact that my ears were still ringing several days later, it was a sensation vastly preferable to what I experienced during the three-minute walk to and from the subway.

With a shortened week and genuinely dangerous temperatures, I once again adopted the strategy of focusing on a neighborhood I already had a head start on: Whitestone, Queens.

I first visited Whitestone about two and a half years ago while covering the adjacent neighborhood of Malba, aka the Beverly Hills of the East Coast, in search of lunch. While Malba boasts plenty of massive Mediterranean palazzos, it has nowhere to eat. Before the Whitestone Bridge opened in 1939, Malba was considered part of Whitestone. Another bridge, the Throgs Neck, forms the neighborhood’s western border.

Historically, most New York neighborhoods didn't really experience growth until train service arrived. Whitestone’s trajectory was different. The Whitestone Branch of the Long Island Rail Road, which was built in 1869, when the area had fewer than a thousand residents, was demolished in 1932 and replaced by the Cross Island Parkway, which split the neighborhood in two. One look at a subway map makes it clear why car ownership rates are so high out here.

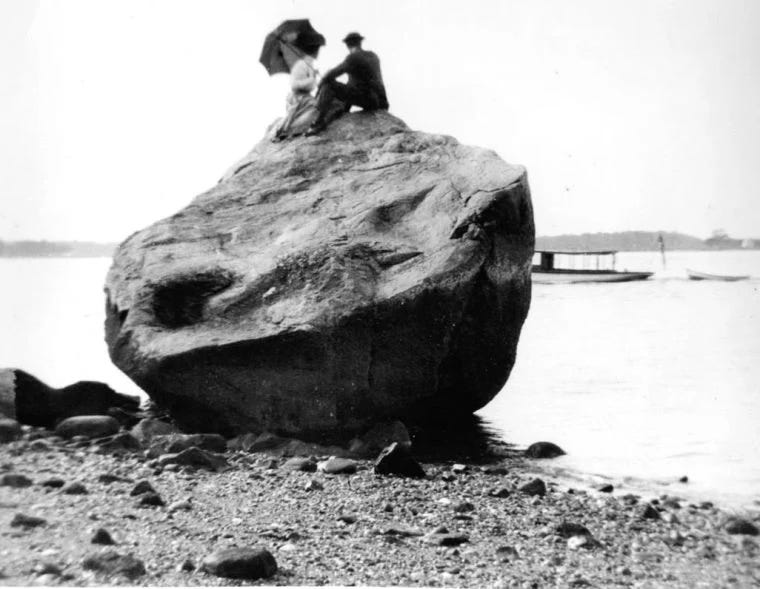

Besides the two massive bridges that tether Queens to the Bronx, and the expressways that funnel traffic toward them, Whitestone’s other borders are 25th Avenue to the south and the East River to the north. It was the massive limestone boulder along the river’s edge that inspired the Dutch farmers who purchased the land from the local Matinecock tribe to name the area Whitestone.

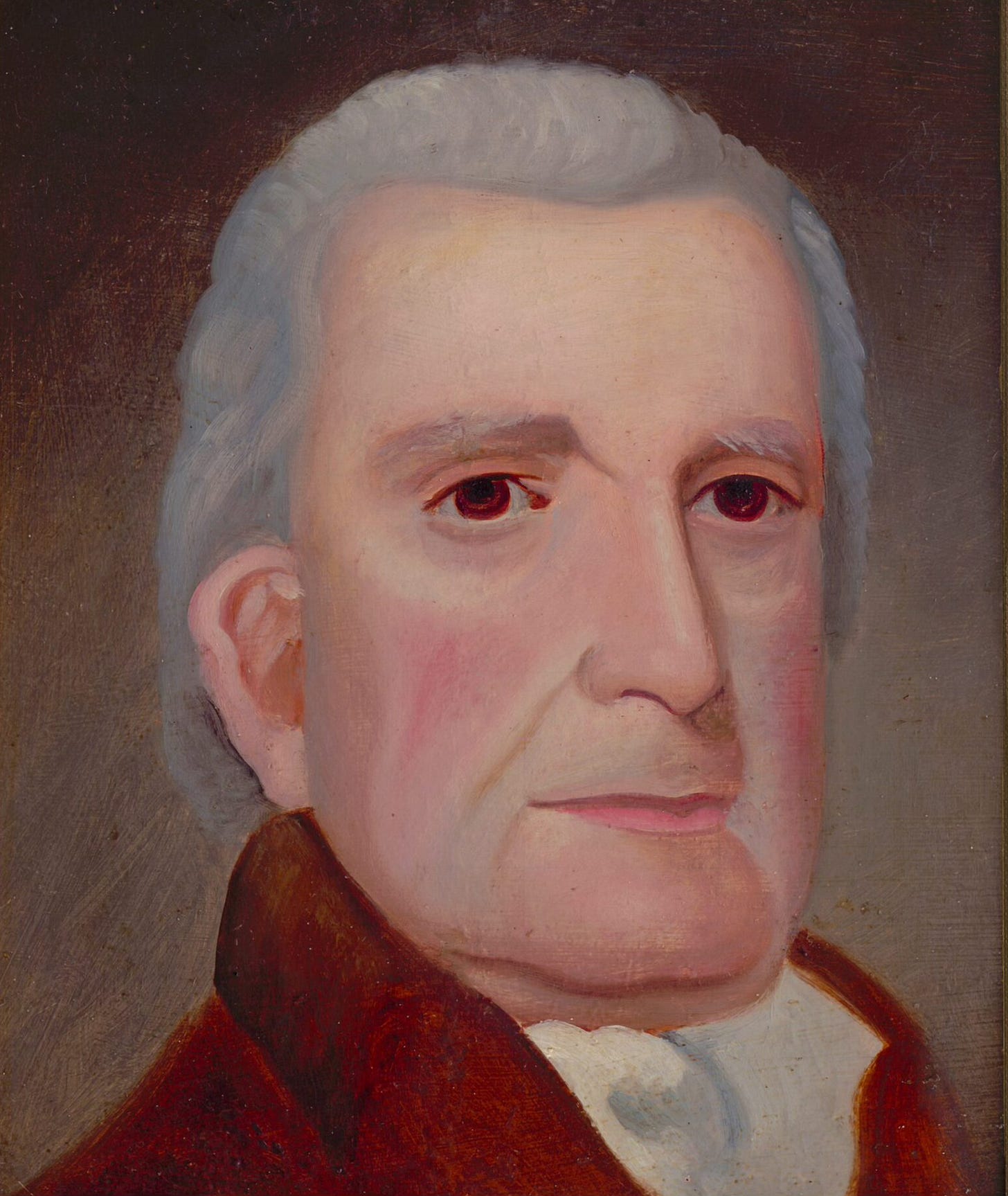

The first of many famous Whitestone residents was Francis Lewis, a successful merchant who was the main supplier of British uniforms during the French and Indian War. Lewis was captured during the war and spent seven years in prison. When he was finally released, the British gave him 5,000 acres of prime waterfront land in Whitestone as restitution.

In 1776, Lewis was one of the 56 delegates who signed the Declaration of Independence. A month later, after emerging victorious from the Battle of Brooklyn, the British, who were known to hold a grudge, sent a warship to destroy Lewis’s house. The soldiers burnt the house to the ground and captured his wife, Elizabeth. Though Elizabeth was eventually released in a prisoner swap orchestrated by George Washington, she never recovered from the pneumonia she had contracted and died in 1779.

CLINTON TO COOKEY

The town was briefly renamed Clintonville after DeWitt Clinton, who achieved the rare trifecta of serving as mayor of New York City, governor of New York State, and U.S. Senator. Clinton lived in Maspeth but had a summer place in Whitestone. His accomplishments, however, were no match for the large white boulder, and in 1854 the locals went back to calling the place Whitestone.

My personal favorite neighborhood name was the short-lived Cookey Ville. The name came about in the 1830s after “a cake and candy woman” got on the wrong boat and was put ashore at Whitestone. “She, being disposed to make the best of her misfortune, walked boldly up to the settlement and soon disposed of her toothsome stock to an idle crowd of men and boys, among whom the incident was the subject of great mirth and gossip.” That an impromptu bake sale would generate enough excitement to inspire a renaming, albeit a temporary one, speaks to the overall pace of things in town.

WALT

There was at least a one-room schoolhouse where, for a brief period in the early 1840s, Walt Whitman taught. The peripatetic poet had recently left a similar position in nearby Woodbury, New York which he described as a “diabolical, and most particularly cursed locality,” reserving particular scorn for his workplace and its “old school-room, dirty-faced urchins, and moth eaten desk.”

Whitman viewed his new surroundings much more favorably:

Bless the breeze that wafted me to Whitestone.—We are close on the sound.—It is a beautiful thing to see the vessels, sometimes a hundred or more, all in sight at once, and moving so gracefully on the water.

The neighbors, however, fared less well:

The principal feature of the place is the money making spirit, a gold-scraping and a wealth-hunting fiend, who is a foul incubus to three fourths of this beautiful earth.

While it’s hard to argue with his closing statement, you have to begin to wonder if Walt was the problem, not his neighbors.

GROWTH

The neighborhood saw its first real growth in the 1850s when John D. Locke opened a large metalwork factory near the shore. As was the practice in those times, he built housing nearby for his workers.

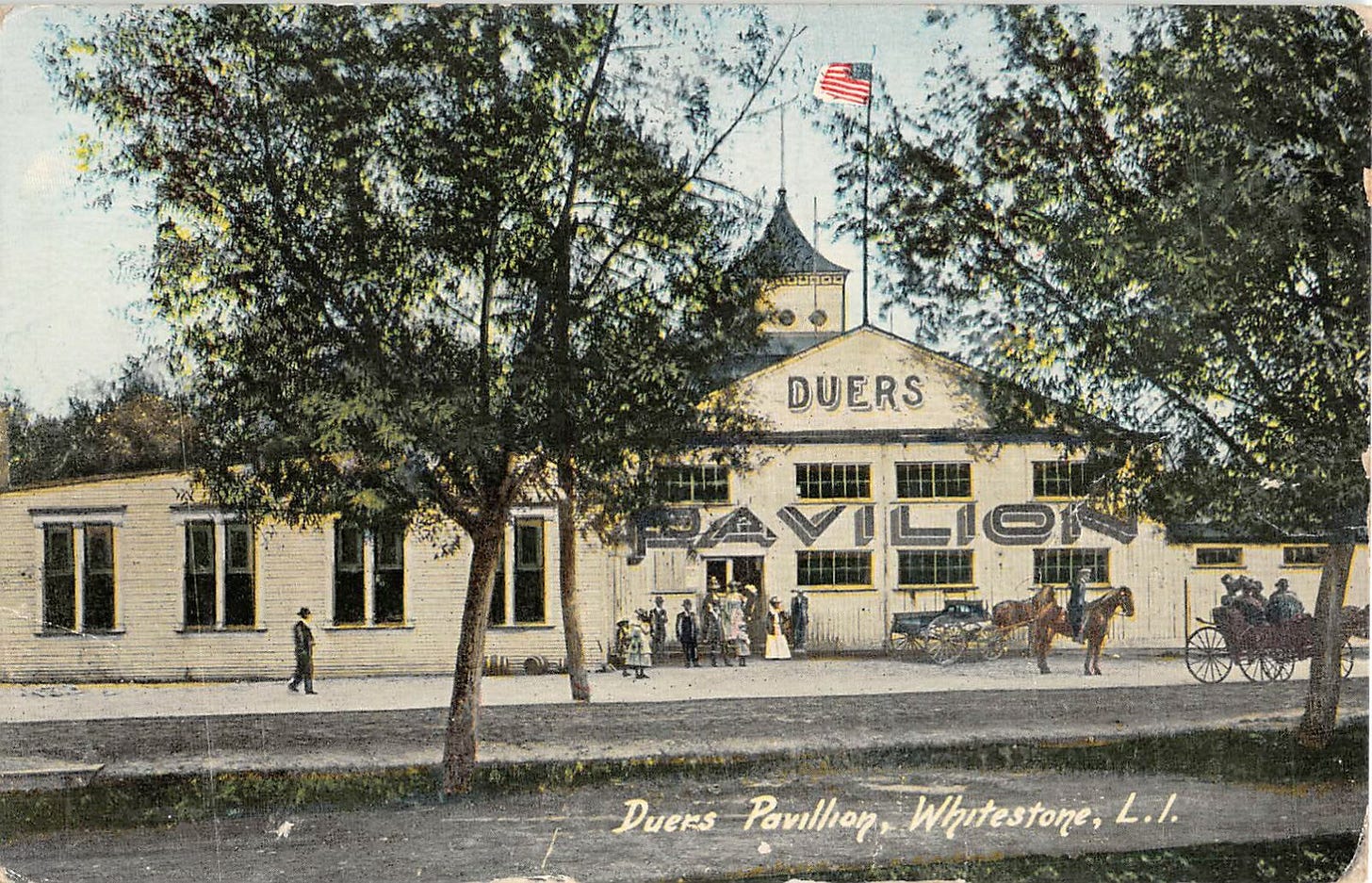

In the late 19th century, like nearby College Point, Whitestone became a weekend destination for city dwellers who would hop on a ferry from the city and head up the East River for a little fun in the sun.

Places like Duer’s Pavilion hosted annual retreats for organizations like the United Bowling Club and something called the Bean Bag Eating Club, whose members would spend the day playing baseball, eating pie and engaging in the era’s favorite spectator sport: Fat Men’s races. Others, like the Pickles from 84th Street, just came to drink.

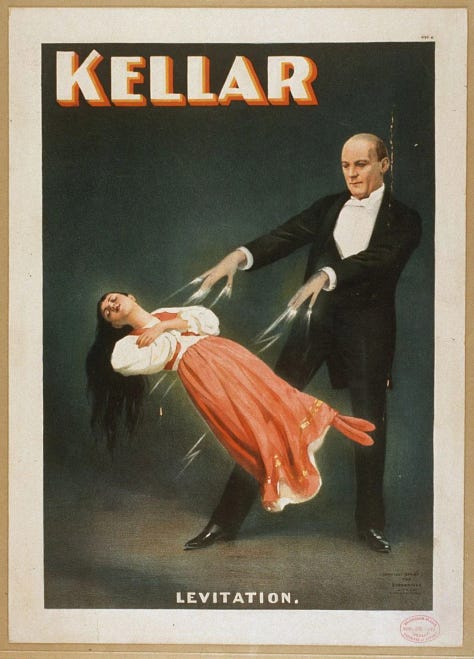

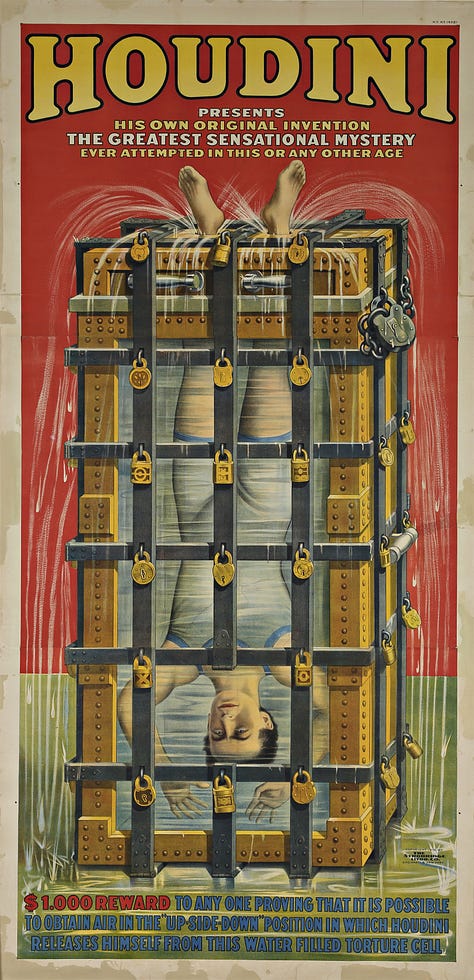

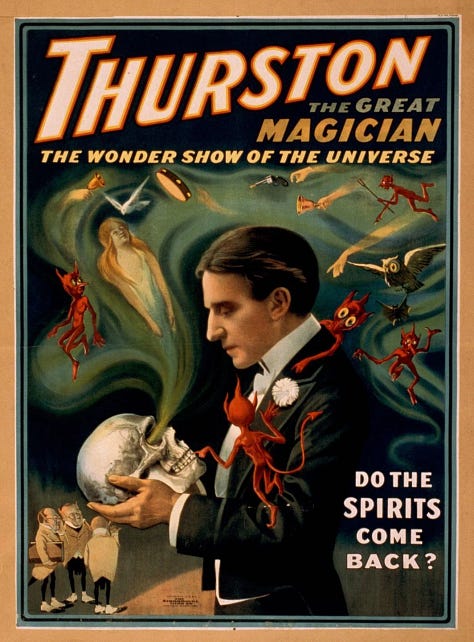

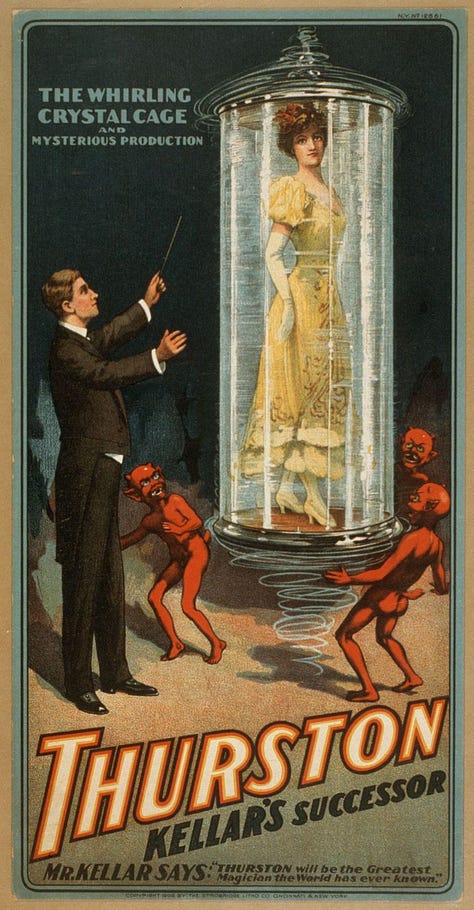

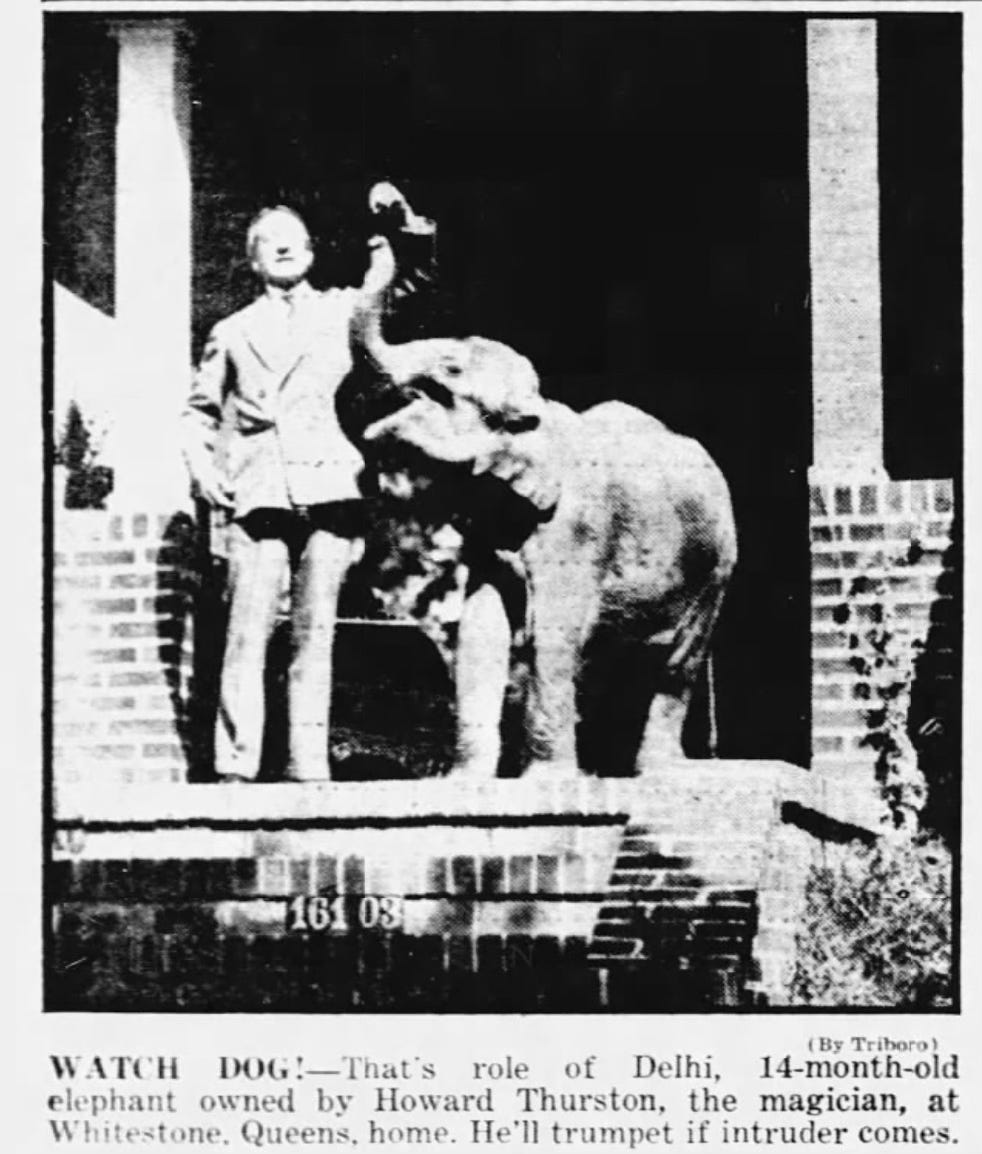

Around the same time, several of the era’s biggest movie stars built estates in the Beechurst section of the neighborhood. Silent film stars like Mary Pickford, Clara Bow, Fatty Arbuckle, and Charlie Chaplin lived in or visited sprawling mansions that overlooked the Sound. The area boasted an unusual density of famous magicians including Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston, who repurposed an old movie studio into a workshop to build his elaborate illusions like the disappearing horse and the buried alive trick.

Thurston had trained an elephant to alert him if an intruder approached the property. Unfortunately, the guard elephant didn't make a peep when anyone tried to leave. One afternoon, a pet monkey belonging to one of his collaborators snuck over the fence and bit 12-year-old Henry Charous. Henry’s mom successfully sued Thurston for $20,000.

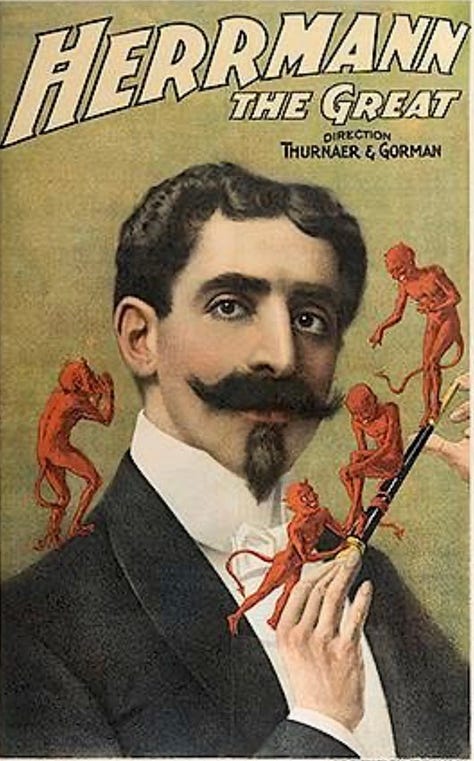

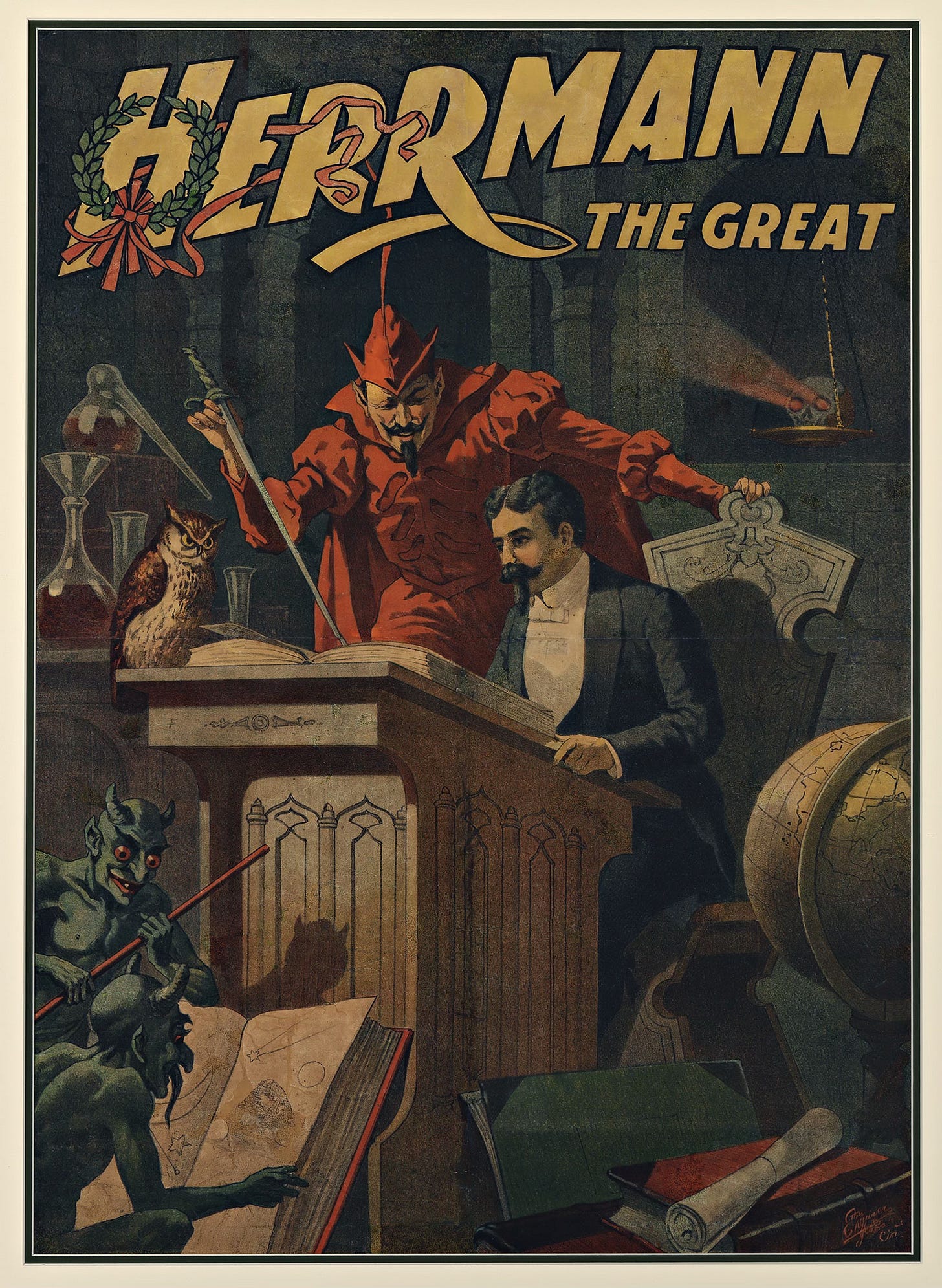

The origins of Whitestone’s guard elephants, attack monkeys and magic workshops can all be traced to one man: Alexander Herrmann, better known as Herrmann the Great.

HERRMANN THE GREAT

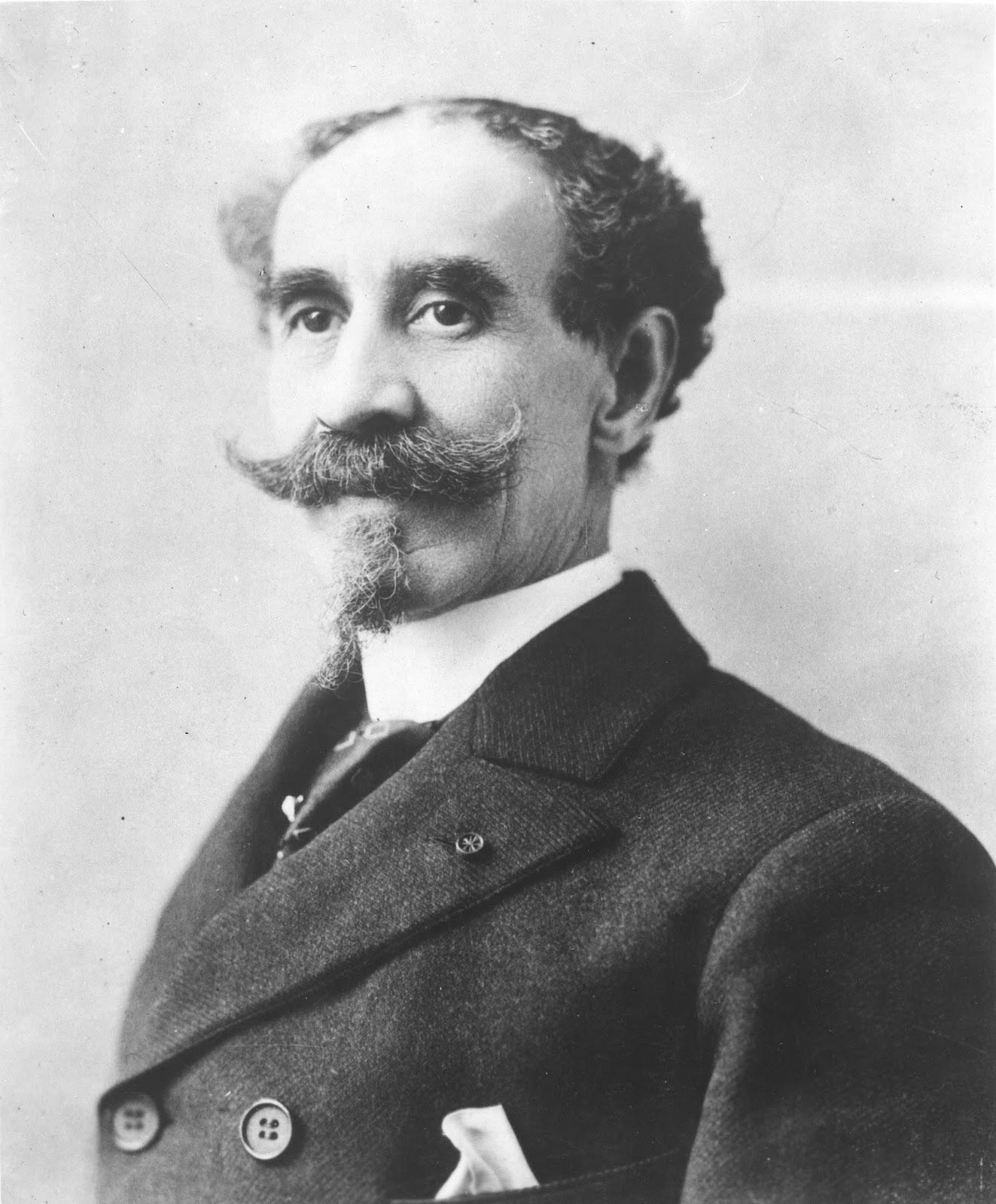

The French-born Alexander Herrmann was the most illustrious illusionist of his time. With his Mephistophelean mien, accentuated by a pointed goatee and twirled mustache, he defined the magician’s look for nearly a century.

The preeminent prestidigitator and his wife, Adelaide, moved to Whitestone in the late 1870s. Their estate, known as Herrmann Manor, sat at the terminus of the Long Island Rail Road’s Whitestone Branch, where Herrmann kept a private railroad car to transport his stage equipment while his yacht, the Fra Diavolo, bobbed just offshore.

Thousands packed theaters to watch Herrmann conjure coins out of midair and perform elaborate illusions like the Cremation or the Bullet Catch, in which a marked bullet was fired at the magician, who, if all went well, would catch it between his teeth or with his hands. Things always went well for Herrmann. They did not for his one-time assistant, William Ellsworth Robinson.

CHUNG LING SOO

After Herrmann’s death in 1896, Robinson struck out on his own. He was no slouch when it came to sleight of hand but, unlike his former employer, he was severely lacking in the charisma department. In 1898, Robinson attended a performance by the popular Chinese magician Ching Ling Foo. Foo’s signature illusion involved wringing a cloth into a large bowl until it filled with water, from which he would then produce a small child. When Foo performed in the United States he offered a $1,000 reward to anyone who could replicate the trick.

Robinson believed he had solved it, but Foo refused to meet with him. In a perfectly reasonable response to the slight, Robinson shaved his mustache and the top of his scalp, clipped on a pigtail, slathered himself in greasepaint and adopted the moniker Chung Ling Soo.

Within a few years he was one of the highest-paid performers in Europe. At one point Chung Ling Soo even accused Ching Ling Foo of copying his act and many in the press took the faux-Foo’s side.

The charade came to an abrupt end on March 23, 1918, at London’s Wood Green Empire Theatre, during Robinson’s variation of the Bullet Catch, “Condemned to Death by the Boxers.” Gunpowder residue in the uncleaned barrel of a musket, which had been accumulating after years of performances, ignited mid-trick, sending a bullet directly into the magician’s chest. The mortally wounded Robinson exclaimed, in perfect English, “Oh my God. Something’s happened. Lower the curtain.” It was the first (and last) time anyone had heard Chung Ling Soo speak.

On a happier note, after her husband’s death, Herrmann’s widow Adelaide dusted off his old tricks and hit the road, eventually earning the name “The Queen of Magic.” She toured as a headliner for over 25 years and successfully performed the Bullet Catch several times.

TWO BRIDGES

Prohibition put an end to most of Whitestone’s weekend crowds and by the 1930s, most of the neighborhood’s movie stars had decamped to Hollywood. True to form, the local magician population vanished into thin air.

The train tracks were replaced by the Cross Island Parkway which was connected to the newly built Whitestone Bridge, constructed by Robert Moses in 1940 to alleviate traffic congestion on the Triborough. In its first full year of operation, 6,317,489 vehicles passed through the Whitestone tolls, producing massive traffic jams while reducing traffic on the Triborough by just 122,519 vehicles.1

Moses’s solution, of course, was to build another bridge. The $92 million Throgs Neck opened in 1961 and within months it too was mired in gridlock. Two years later, traffic on the Whitestone Bridge was back to its earlier levels.

TWO DELIS

Any neighborhood big enough for two bridges is big enough for two 24-hour delis, even if those delis happen to be right across the street from one another.

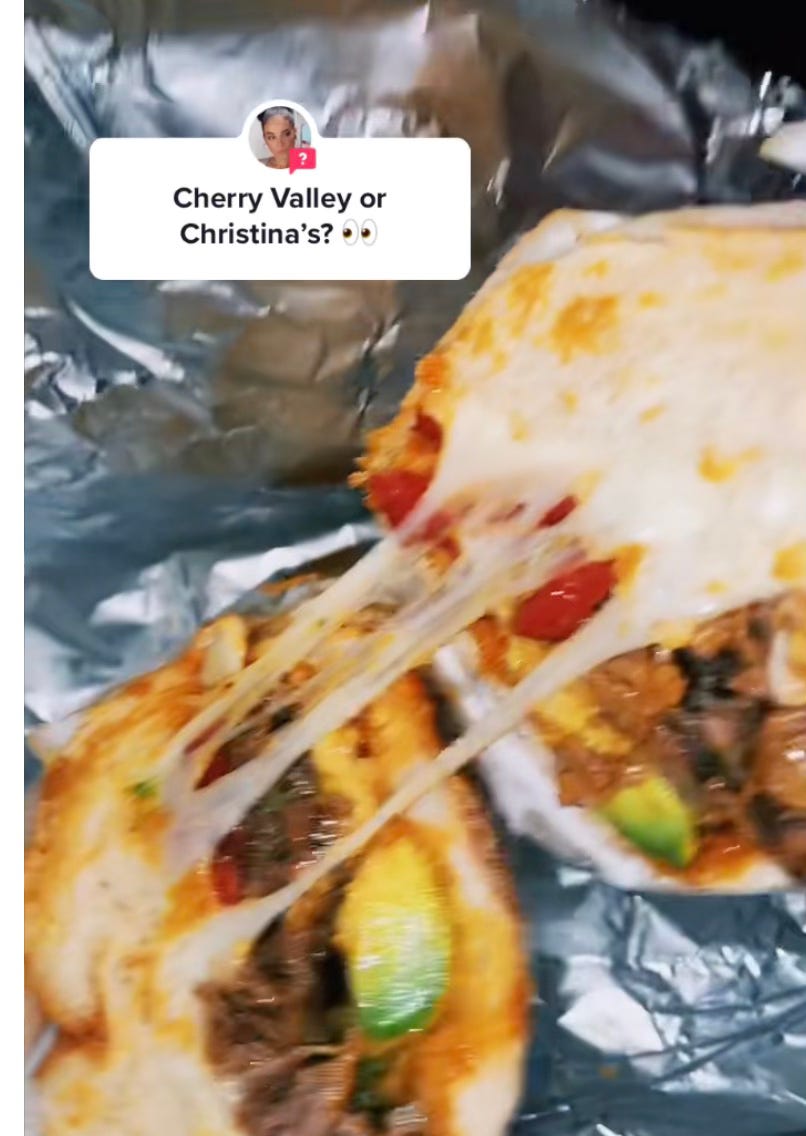

Neighborhood stalwart Cherry Valley opened in 1979, quickly gaining a cult following based on the success of the Bushman sandwich: a chicken cutlet with bacon, gravy, and American cheese on a toasted garlic hero. Other sandwiches on the extensive Cherry Valley menu follow a similar logic. The recently unveiled Verizon Fios hero features chicken tenders, waffle fries, mozzarella sticks, coleslaw, and the secret Cherry Valley sauce.

Then, in 2005, Cristina’s Deli and Grill opened across the street with a suspiciously similar lineup, including the Super Mario, the Billy Got Bombed, and the aptly named Heart Attack: a chicken cutlet topped with melted mozzarella, spicy fries, onion rings, special sauce, and bacon.

Amazingly, the delis (both owned by men named Danny) have survived and reportedly have lines at the door at 3AM on weekends. They’ve also spawned a cottage industry of TikTok influencers who post videos of themselves devouring the greasy heroes (#coronaryheartdisease) and debating which deli reigns supreme. I chickened out and opted for the far less hyped Taco Azul down the street.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

Not much going on sonically this week. Some crunching snow (and labored breathing) under the Whitestone Bridge and a couple of crows.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

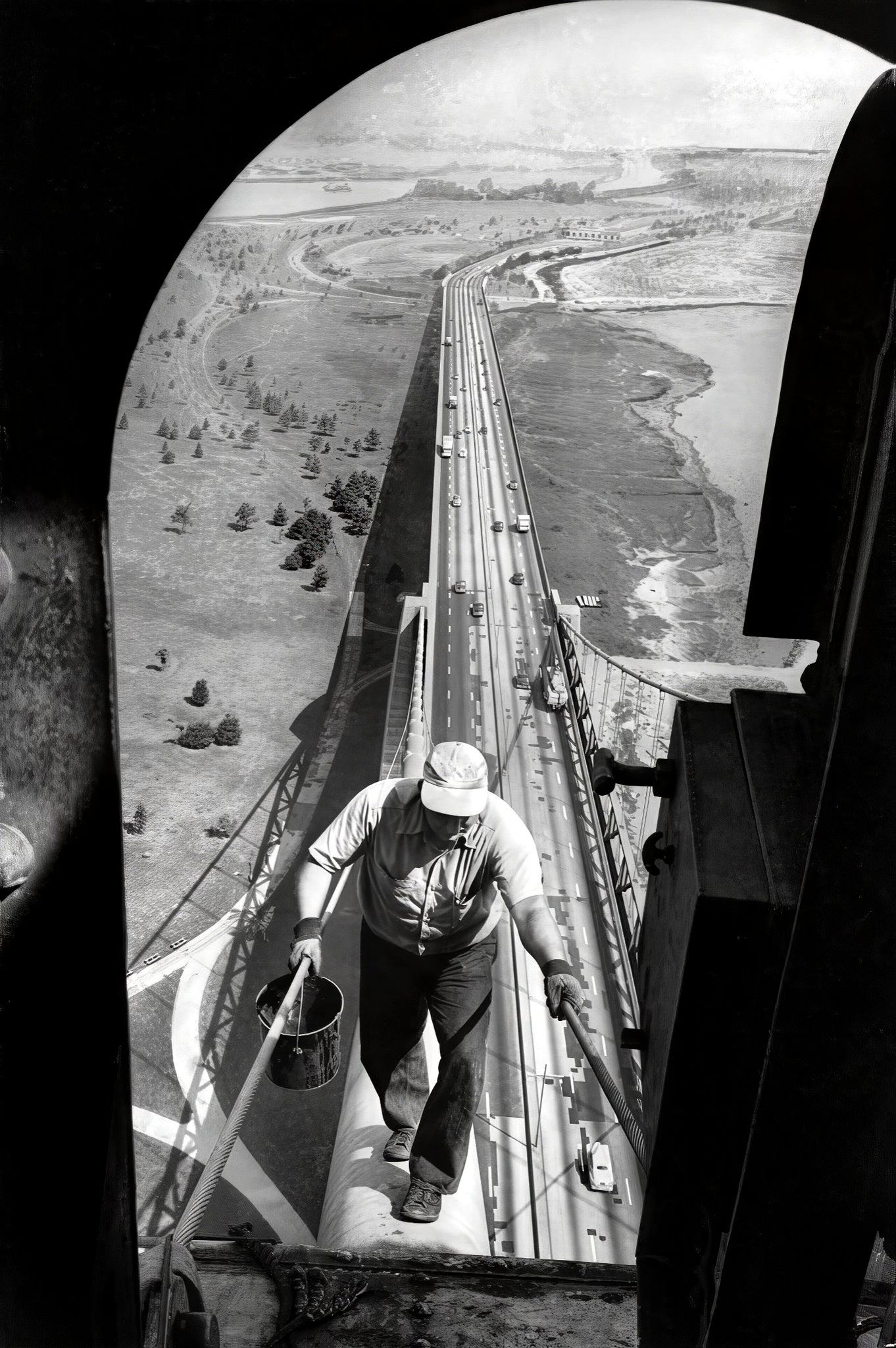

Another week, another famous photographer I had never heard of. Ernie Sisto was born in 1904, in Princeton, New Jersey. At 14 he worked as a “squeegee boy” for International News Photos; by 16 he was promoted to photographer. Three years later, he joined the New York Times, where he remained for nearly 50 years.

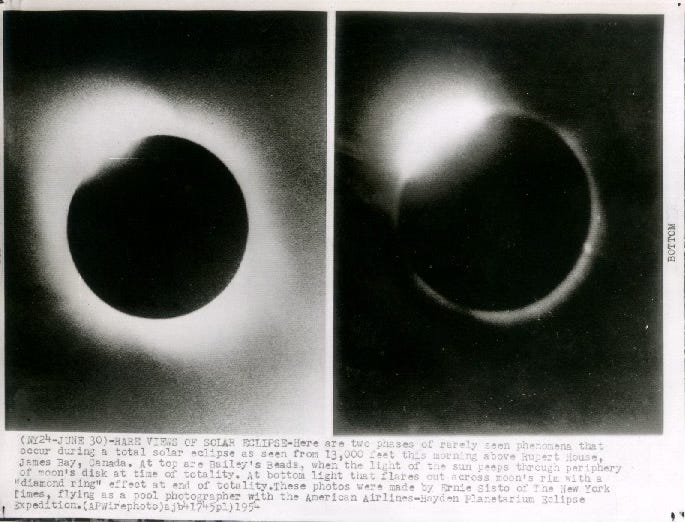

Sisto invented the first flash synchronization for the Speed Graphic shutter (the Sisti-Gun) and made thousands of pictures for the Times. While his specialty was sports, he covered everything from the crash of a B-25 bomber into the Empire State Building to the 1954 solar eclipse.

He took what may be his most famous photograph, Fearless Painter, while straddling a cable 363 feet above the Whitestone Bridge.

ODDS AND END

If all the above talk of Bullet Catches and feuding magicians sounds vaguely familiar, you're either a magic buff or you've seen Christopher Nolan's The Prestige (2006). Nolan's Chung Ling Soo is a composite of Soo and Foo, but you can watch the only existing footage of the real Robinson (as Soo) here.

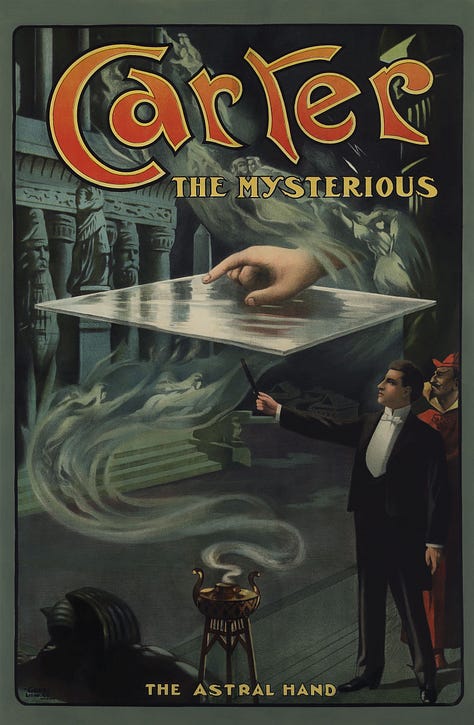

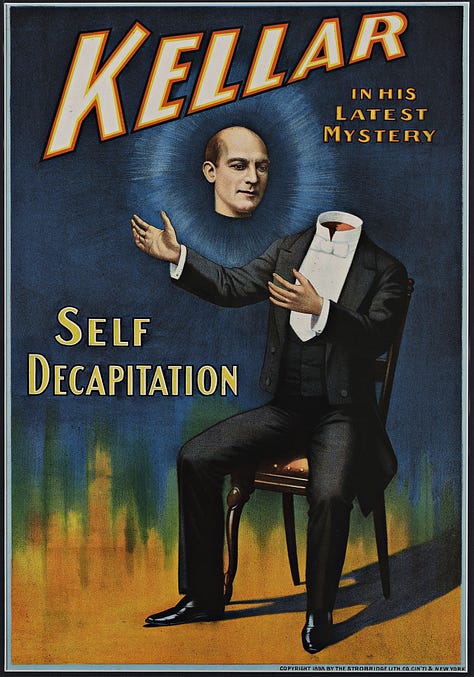

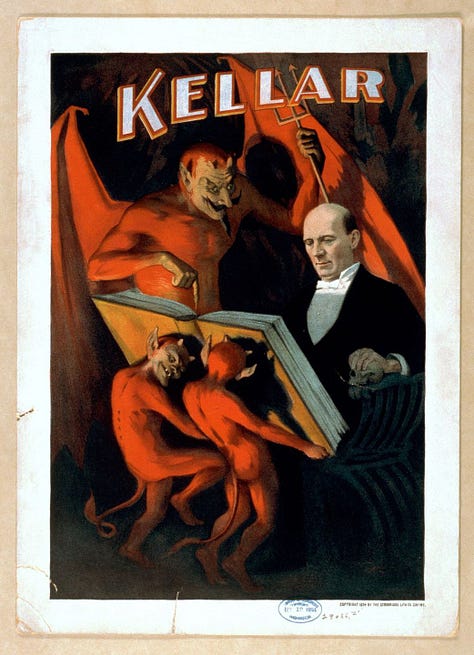

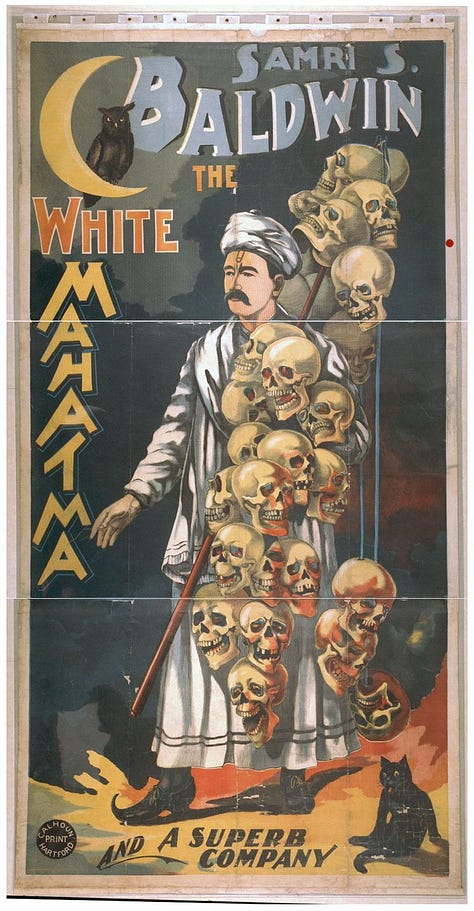

🎩 I can’t get enough of these magician posters!🐇

🪄Thanks to Connor for letting me know about the NYPL’s current Mystery and Wonder: A Legacy of Golden Age Magicians in New York City exhibition which is at the Library for the Performing Arts at 40 Lincoln Center Plaza through July. 🪄

Gussie Davis was one of the first Black songwriters to achieve major success in Tin Pan Alley. His song "Irene, Good Night" was later recorded as Goodnight, Irene by one time Alphabet City resident, Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter.

Other songs, like “Maple on the Hill,” became standards in folk and bluegrass circles, recorded by hundreds of artists including Doc Watson, Ralph Stanley, and the Carter Family. Near the end of his life, Davis bought a house in Whitestone, where he died in 1899.

Caro, Robert A.. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

Love those twisting brick columns! Also feeling a bit of camera lens envy from that 1947 photo of Ernie Sisto.

You have a teenage daughter? All this time I’ve been imagining a young carefree guy roaming the neighborhoods of New York taking pictures and doing all that research. 🧐 It doesn’t, in any way, change how I view your wonderful and interesting work. It’s just funny how I pictured you.