A programming note: As summer tends to bring a natural dip in readership, I’m easing the publishing pace a bit. For the rest of July and into early August, I’ll be shifting to a biweekly schedule. This slower rhythm will give me time to catch up on research, dive into a few collaborations, and finish the first in what I hope will be a series of neighborhood zines. I figure your inbox could probably use a bit of a summer breather, too.

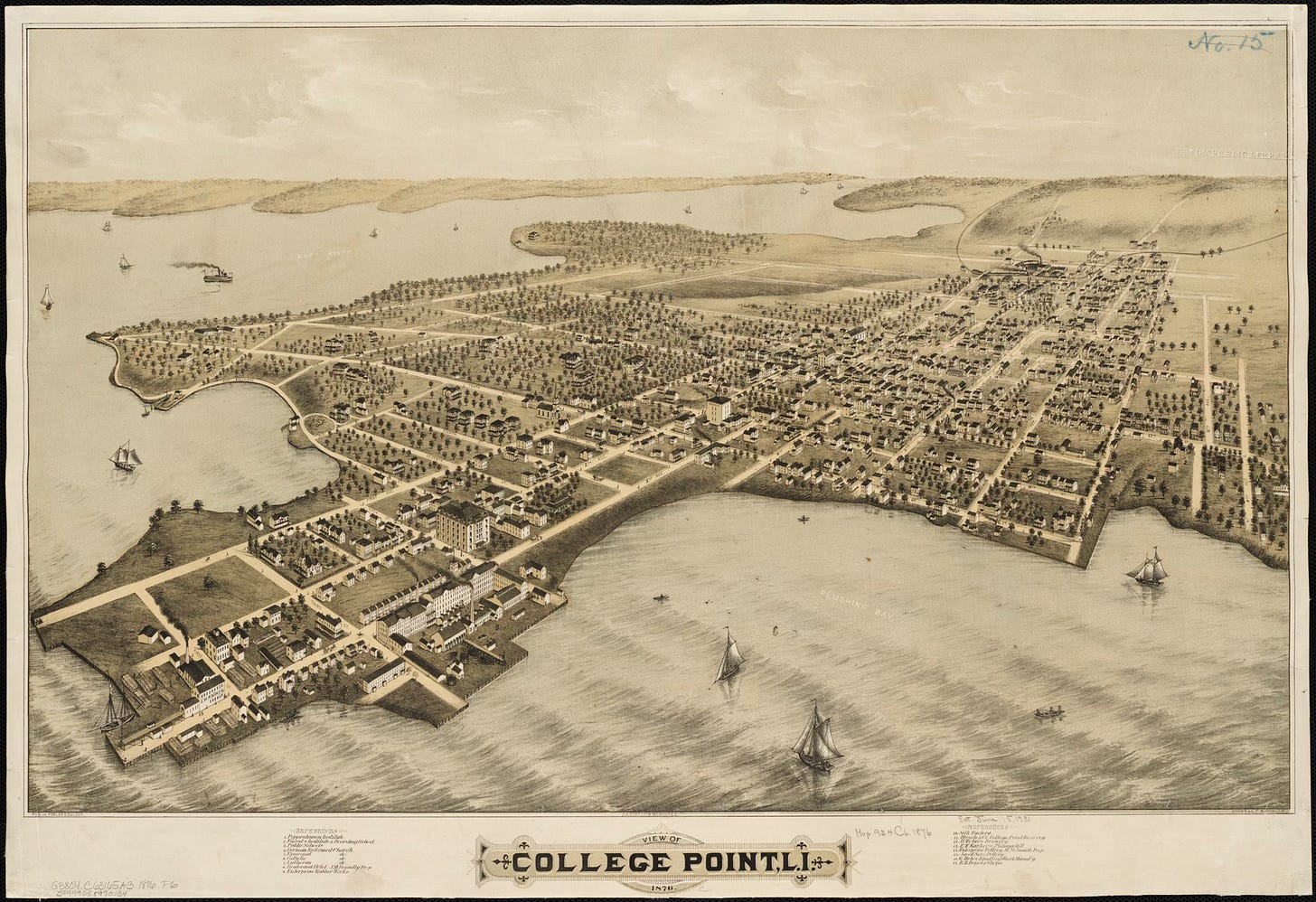

Few New York City neighborhoods are as clearly delineated as College Point, Queens. The six-lane Whitestone Expressway cuts a hard boundary between this chunky peninsula and Flushing to the south, while Flushing Bay and the East River define its remaining edges. The only ambiguous border lies to the east, where the neighborhood fades into the tony enclave of Malba, the Hamptons of Queens, but most agree 138th Street is the dividing line.

The neighborhood began as a 19th-century company town centered on Conrad Poppenhusen's rubber factory, and to this day it retains an industrial character. Facilities like the New York Times printing plant, the Pepsi bottling plant, and several concrete factories still anchor the community. Once a predominantly Irish and German enclave, it has evolved into a diverse, working-class neighborhood home to first and second generation families from China, Korea, and Latin America.

EARLY YEARS

In 1645, Captain William Lawrence, an Englishman by way of Massachusetts, arrived in New Netherland and acquired 900 acres of land just north of a swamp that separated it from the rest of Flushing. The Lawrence family, College Point’s first European settlers, farmed the land, built homes and orchards, and called the area Lawrence’s Neck. They held the land for over a century, until damages suffered during the Revolutionary War forced them to gradually sell off parcels. These were eventually subdivided into smaller villages like Strattonport and Flammersburg.

In 1836, Reverend William Augustus Muhlenberg, the “father of church schools” in the US, founded the St. Paul's College and Grammar School. Though the school never secured a collegiate charter and closed by 1850, its short-lived presence gave College Point its name.

RUBBER BARON

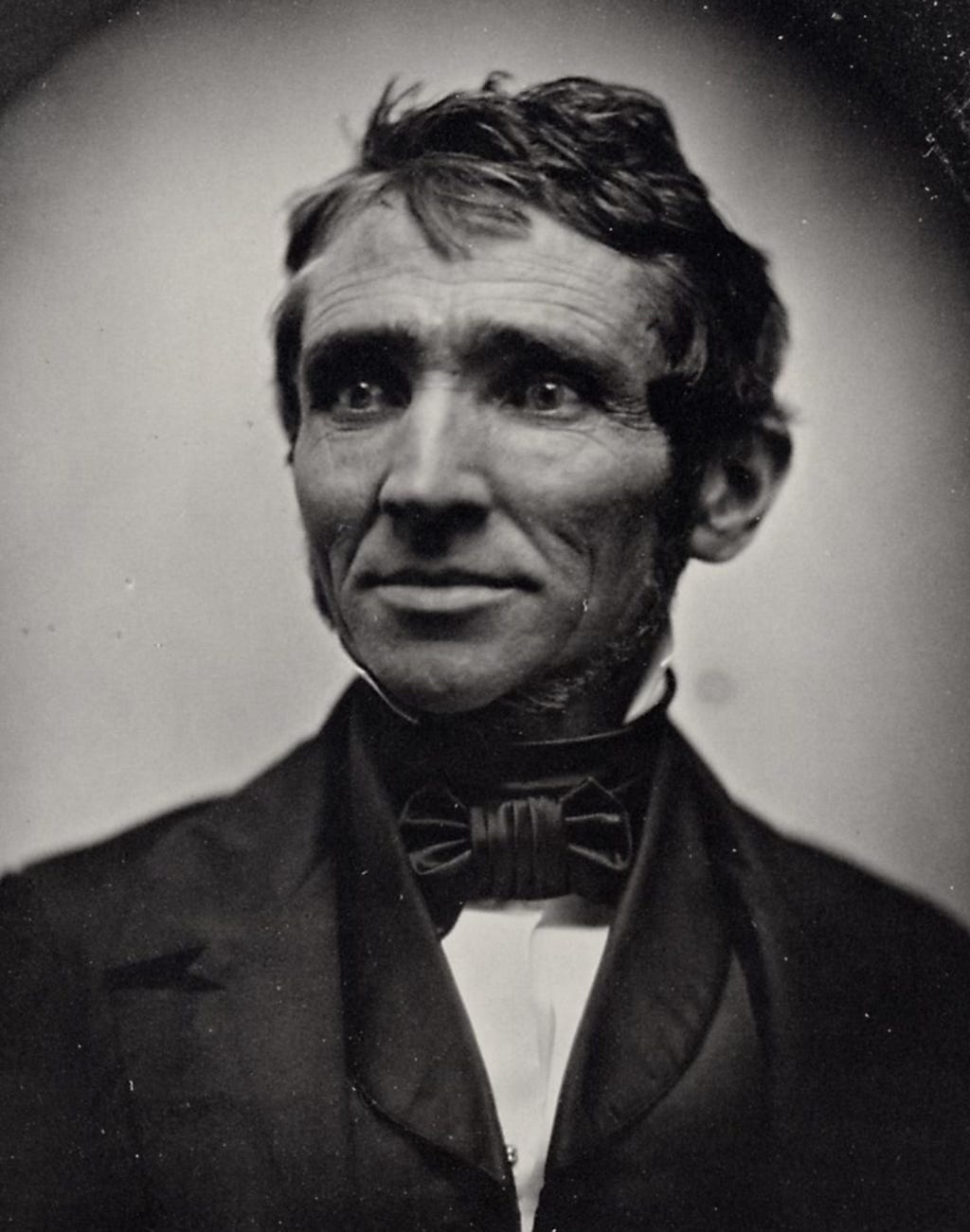

In 1854, just a few years after the school closed, College Point’s most famous resident, Conrad Poppenhusen, moved to the neighborhood.

Though he sounds like a protagonist in a Terry Gilliam movie, Poppenhusen was an atypically progressive capitalist, a benevolent tycoon, in a time when robber barons were all the rage.

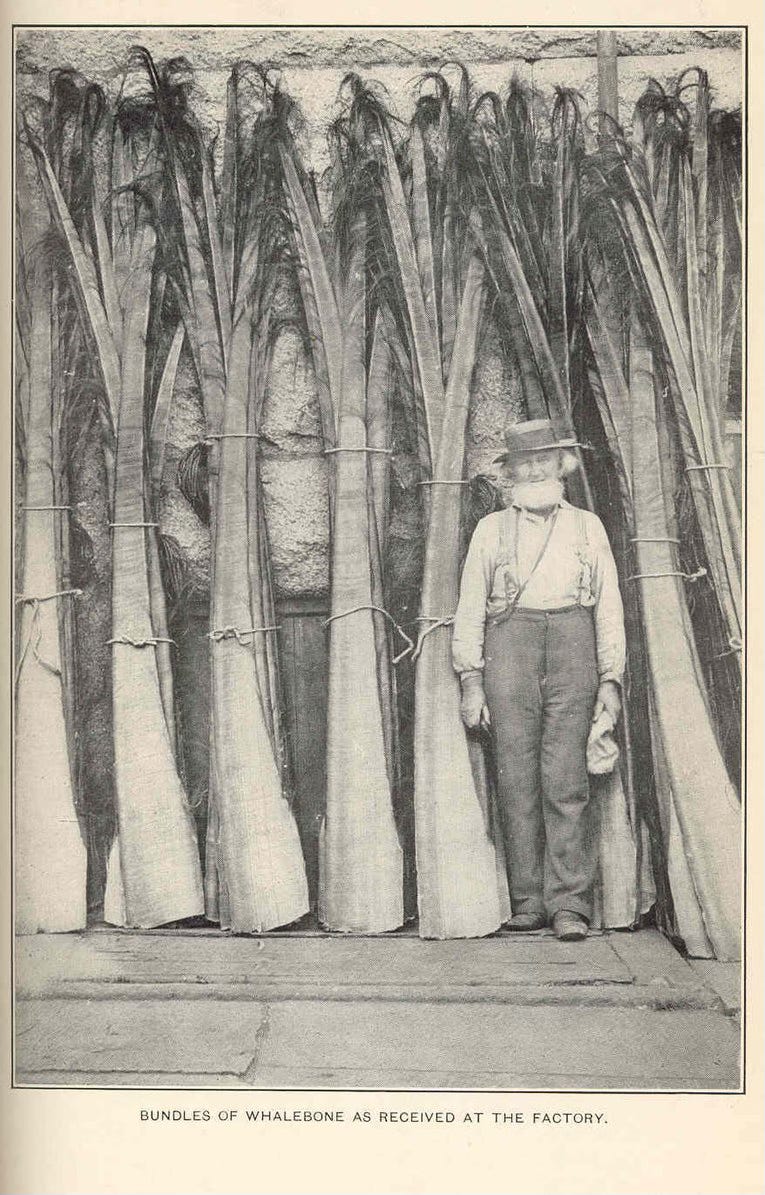

The German-born Poppenhusen moved to the US to open up a whalebone factory on the banks of the East River. The Meyer and Poppenhausen Whalebone factory is the tallest visible building in Williamburg in the below 1848 painting.

Whalebone, used in everything from corsets to buggy whips and backscratchers, is actually not bone at all but baleen, the long strips of keratin that descend like a set of furry Venetian blinds from the upper jaws of the planet’s largest whales. These massive cetaceans gulp up to 70 tons of water and push it through their baleen, trapping a smorgasbord of krill, plankton, and the occasional herring in the process.

But by the 1850s, whales were becoming increasingly scarce, and a replacement for baleen was needed.

Enter Charles Goodyear who had devoted his life to figuring out how to make the milky white sap from the rubber tree into a product stable enough for everyday use.

Somewhere along the line, Goodyear, who was perpetually in and out of debtor's prison, crossed paths with Poppenhusen who believed in his work enough to finance it. After Goodyear finally perfected vulcanization (heating latex with sulfur to make it durable), he granted Poppenhusen exclusive rights to the process for several years.

In 1859, Poppenhusen laid the cornerstone of the India Rubber Comb Company on the shores of Flushing Bay. For decades, the factory churned out corset stays, syringes, and combs—including the infamous cootie combs whose tightly spaced teeth separated lice from hair in much the same way baleen trapped squirming schools of krill.

Poppenhausen paved streets, constructed housing and stores, laid water and sewage systems, and connected the peninsula to Flushing with a cobblestone road. He founded the Flushing and North Side Railroad and built the Poppenhusen Institute, which housed a library, vocational training programs, the country’s first free kindergarten, and even a jail. His workers received health and death benefits, bonuses for Civil War service, and job guarantees upon their return.

Poppenhusen retired wealthy in 1871, but his sons mismanaged the family’s railroad investments. By 1877, he declared bankruptcy, dying with nearly $4 million in debt.

LITTLE HEIDELBERG

Poppenhusen’s rubber factory and ferry service to Manhattan helped attract a wave of new residents, many of them German. The neighborhood earned the nickname "Little Heidelberg," and its beer gardens and beach resorts thrived along the clean shores of Flushing Bay.

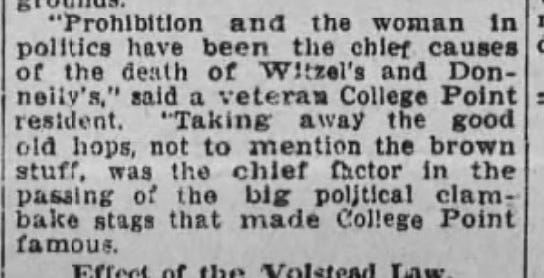

Witzel’s and Donnelly’s were two of the most popular resorts, both famous for their clambakes. Summer weekends drew locals and visitors alike. Groups like the Associated Traveling Salesmen and the Beethoven Maennerchor held their annual outings in College Point. Local politicians lavished constituents with beer and chowder in hopes of securing their votes.

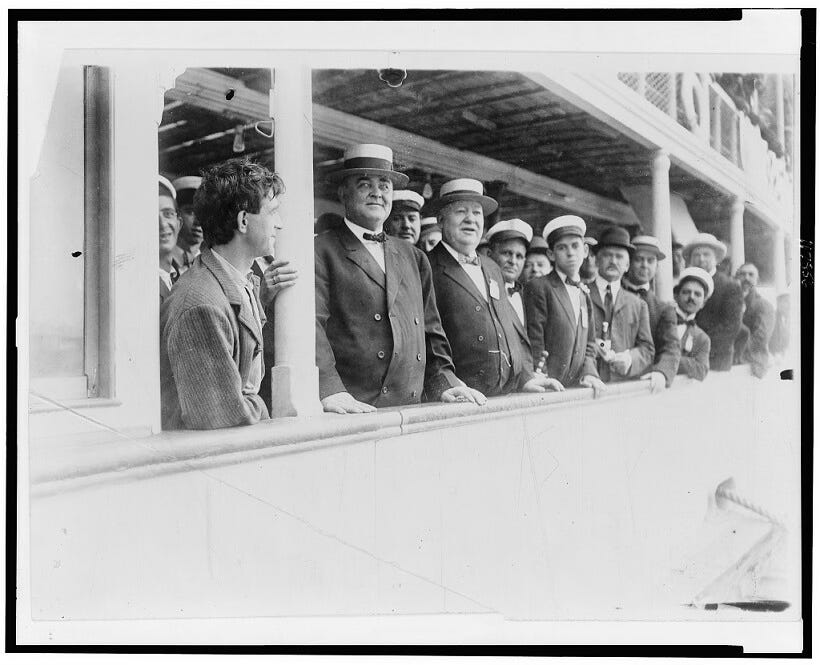

None more so than Tammany Hall kingpin, “Big Tim” Sullivan, one of the most corrupt politicians in New York City history, who was known for his elaborate Labor Day “chowders.”

For several years, on the first Monday of September, thousands of his supporters would jam onto waiting ferries to make the passage across the East River to College Point for an afternoon of drinking, poker and quasi athletic competitions like the huckleberry pie eating contest. Contestants had to eat half a pie, run 200 yards, and then eat a whole pie. The 1908 winner, Mike Sautinoli, managed the feat in an impressive 7 minutes.

Other events included three-legged races, backward races, and what was called the Fat Men’s race.

THE GLORY OF ADIPOSE

The few decades straddling the end of 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries were the golden age of Fat Men’s Clubs, organizations whose main requirement was that their members weigh at least 200 pounds. These corpulent clubs of conspicuous consumption counted politicians, lawyers, doctors and businessmen among their ranks. It was the last days of Americans equating obesity with prosperity.

“The consumption of food was a sacrament of success. A man who carried a great stomach before him was thought to be in his prime….America was a great farting country.”

E.L. Doctrow, Ragtime

Clubs like the Fat Men's Association of New York, the Jolly Fat Men's Club, and the United Association of the Heavy Men of New York State held annual events featuring weigh-ins, banquets, and prizes for the heaviest participant (often an entire pig).

Though many club members were among the country's elite (or more likely because of it), newspaper reporters delighted in describing the extent of their avoirdupois. This article which describes the annual clambake of the Connecticut Fat Man's Club and the re-election of its president, Philetus Dorlon, is unhinged.

He is huge, he is ponderous, his obesity borders on the infinite; and the most hardened lean man cannot gaze upon his magnificent proportions without being unconsciously made purer and holier.

Gradually, as doctors and insurance companies began to sound the alarm that not being able to button your pants was less a sign of success, and rather a one way ticket to an early death, being overweight fell out of favor. The New England Fat Men's Club, which had once counted 10,000 men among its ranks, limped into the mid-1920s with only a handful of members remaining before finally closing its doors

Meanwhile, Prohibition spelled the end of College Point’s beer gardens. A 1921 Times Union article noted that the local motto had shifted from “Eat, Drink and Be Merry” to “Eat, Drink and Try to Be Merry.”

GOODYEAR RETURNS

Meanwhile, on the other side of College Point, freelance aerial photographer Anthony “Speed” Hanzlik was hard at working turning a patch of vacant swampland into an airport. Before LaGuardia opened in 1939, Flushing Airport was the busiest in New York City, serving private pilots, skywriters, and flight schools. It even hosted the Goodyear Blimps, an unintentional nod to the area’s rubber roots.

But by the 1980s, Flushing Airport’s proximity to LaGuardia made it a safety hazard, and it was shut down in 1984. While there have been several proposals on what to do with the former airport, including construction of a new blimp port and museum, the vacant patch of land has remained virtually untouched. The abandoned hangers have been demolished and the once busy runways have succumbed to the swamp, a submerged palimpsest visible only from above.

ADVENTURER’S INN

From the mid 1950s to the late 1970s, Adventure Park, a ramshackle amusement park operated in the shadow of Flushing Airport. Originally a hodgepodge of independently owned and operated rides, castoffs from amusement parks like Freedomland in Co-op City and Coney Island, the park was bought by entrepreneur Harold Glantz in the 1960s, who rebranded it "Great Adventure Park." Despite the new name, everyone called it Adventurer's Inn, after the adjacent restaurant and arcade topped by a 25-foot illuminated sign.

After years of complaints from residents of neighboring buildings, the park was condemned in 1973. Glantz kept the park running for several more years with support from local religious and political figures, but the city seized the land in 1978, claiming it was needed for an industrial park. The restaurant and arcade hung on until a fire destroyed them in the late ’80s.

These eerie pictures by photographer Bill Brent capture the last days of the abandoned amusement park.

While it is tempting to root for the underdog in a story about a humble amusement park impresario up against the ruthless machinery of bureaucracy, a look into Harold Glantz’s many side hustles complicates the narrative.

Before his fairground days, he was co-owner of Bagel Boys and Bagels U.S.A., mob-affiliated bagel shops that were involved in several union busting efforts and pay to play schemes. Who knew the mob were in bagels?

In the '90s, Glantz was convicted of wire fraud and conspiracy after defrauding the Salvation Army of $4 million.

The industrial park never materialized and today, the land that used to be home to the Batman Slide and Flihgt to Mars is home to a shuttered Toys “R” Us, slated to become a Tesla dealership.

Nearby are the Promise Megachurch—the largest Korean church in NYC—and the New York Times printing plant.

In 2014, the city opened a 32-acre NYPD Police Academy just blocks from the former airport. In addition to classrooms, an auditorium and a gym, the 750,000-square-foot “horizontal skyscraper,” houses a tactical village with a fake bank, fake apartments, a fake grocery store, a fake restaurant (“New York City Bistro”), and a real subway car and (fake) platform. There are also three mock court rooms: Supreme Court, Criminal Court and Traffic Court where recruits can practice testifying.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio comes from a recording I made this June along the edge of Flushing Bay, woven together with a clip I captured in College Point over two years ago using just my iPhone. That rough snippet was the spark that led me to start incorporating field recordings into this project. A few days later, I ordered my first microphones.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

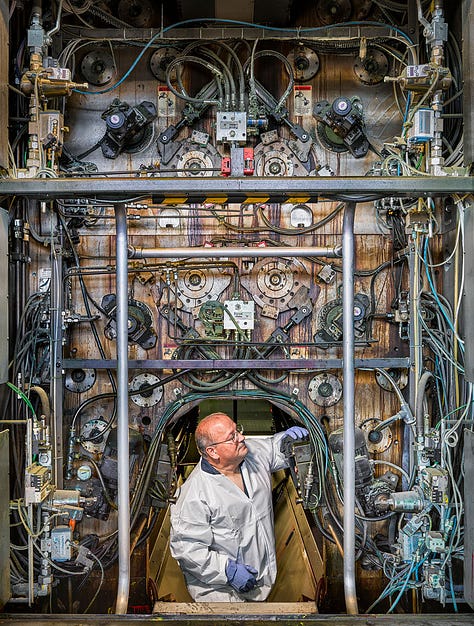

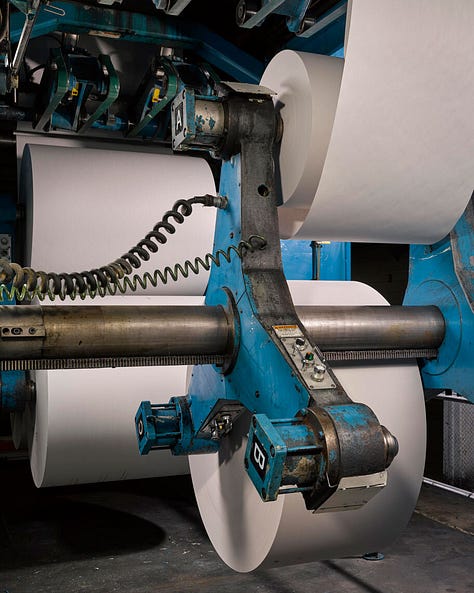

This is the third time I’ve featured Chris Payne’s work here—first with his photos of the Steinway factory in Astoria, and more recently in Bellerose Manor, where I highlighted his images from the Creedmoor Mental Hospital.

The remarkable photographs I’m sharing this week come from the Daily Miracle, a two-year commission by The New York Times to document the inner workings of its College Point printing facility. Starting in 2017, Payne made over 40 visits to the plant to capture the people, presses, and processes behind the production of the Times. The images are accompanied by an essay from the great Lucy Sante.

Unlike its digital counterpart, the physical newspaper is not just a transient occurrence along an ongoing stream; it is a singular phenomenon, which happens every day. The city may no longer feature vendors shouting the main headline at passing commuters, but that headline still carries a sense of urgency, can still thrill or appall when caught unexpectedly in a sidelong glance. A newspaper is a measure of days, an index of passing time. Its front page compresses the significance of a unique date into a rectangular field of words and images, its jarring list of specifics unforeseeable until press time. Why else would Picasso and Braque have chosen the newspaper as both their model and their source when they began making collages in 1912? How else could filmmakers convey the galloping speed of history but with a process-shot montage of spinning newspaper front pages? How else would kidnappers prove that their victims were still alive on a given day other than by photographing them holding that day’s Late Final?

Here is a link to the piece in the New York Times

ODDS AND END

How New York’s Bagel Union Fought — and Beat — a Mafia Takeover is a great article by Jason Turbow about the Mafia’s foray into bagels.

No write up of College Point is complete with at least mention of Spa Castle, 100,000 square feet of saunas, pools, and health code violations. In 2014, an 84-year-old man was found unconscious while submerged in a hot tub and later died. Two years later, a 6-year-old girl nearly drowned in when her hair got caught in a pool vent. A 2016 New York Post article goes into a little too much detail on the “splashy sexcapades” and “full-on, urban high-school orgy” that seem to be a daily occurrence at the supposedly family friendly spa. that resembles “the set of a porn movie.”

Believe it or not, there was even a Fat Man’s Club in France and here is the video footage to prove it.

College Point Class Conflict Pub Crawl. An interesting article from a College Point native, Rob Bellinger who writes the website, The Manic American. Bellinger grew up in College Point in the 80s.

Apparently, the Flihgt to Mars ride at Adventure's Inn required riders to get past someone in a gorilla suit who would jump out of the darkness to startle them. Perhaps expecting an actual Martian encounter, riders didn't take kindly to the gorilla scare and often retaliated with physical attacks. After six would-be gorillas quit in as many hours, Glantz turned to his 11-year-old son Jamie for the role.

We must revive that pie-run-pie contest!

I love all of this