The Bowery is one of New York’s oldest neighborhoods, though today, the name applies to little more than a mile-long stretch centered around its namesake avenue. Over the centuries, this part of southern Manhattan has been a site of constant change, beginning with the transformation of verdant salt meadows and marshes along a Lenape footpath into wheat fields cultivated to sustain the residents of New Amsterdam.

Those farms eventually gave way to lavish estates and pleasure gardens in the north and cattle yards and abbatoirs in the south. For a time, the neighborhood was the city’s premier entertainment district, only to later become a haven for prostitutes and pickpockets.

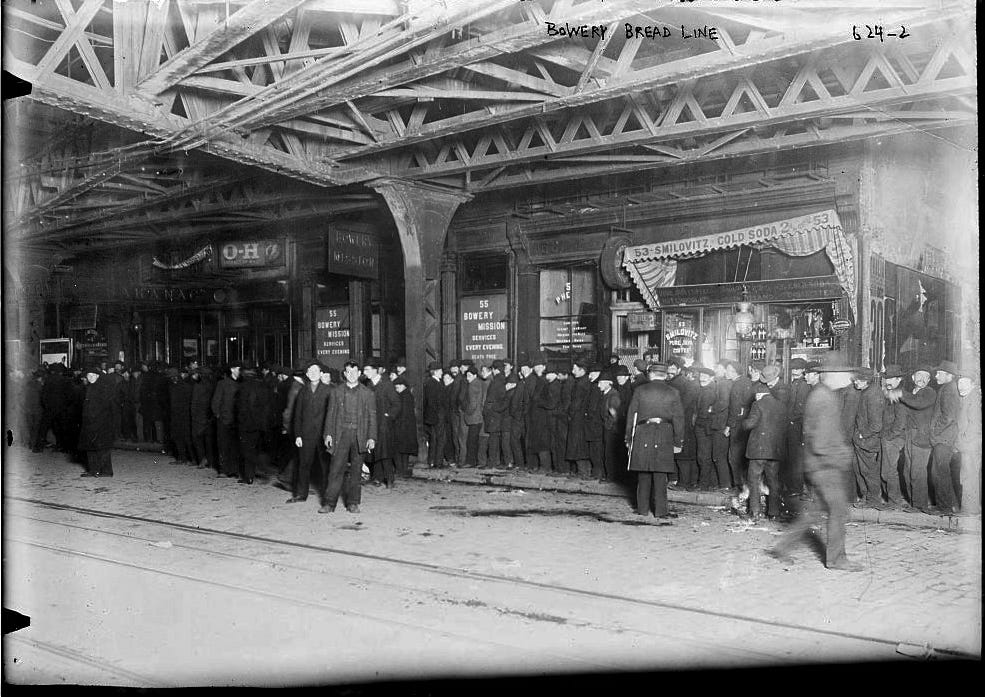

By the early 20th century, the Bowery had earned the reputation of being the “last stop on the way down,” a boulevard for the forgotten, lined with countless SROs and flophouses. The Bowery Mission, Salvation Army, and YMCA were some of the first organizations to minister to the city’s homeless population, all setting up shop in the neighborhood.

Today, a former Salvation Army shelter has been replaced by a boutique hotel that blends “the functional perfection of Finnish saunas, Japanese bento boxes, rock-cut cliff dwellings of prehistory, and John Cage’s 4’33.” Many of the old flophouses have been transformed into modern accommodations for wealthy tourists or replaced by glass-and-steel residential towers that threaten to erase the last vestiges of the old neighborhood.

Despite all these changes, traces of the past remain. You can still see the Early Federal-style townhouse at 18 Bowery, built in 1785 for butcher Edward Mooney. Mooney built his home to be close to the slaughterhouses and cattle yards where he made his living.

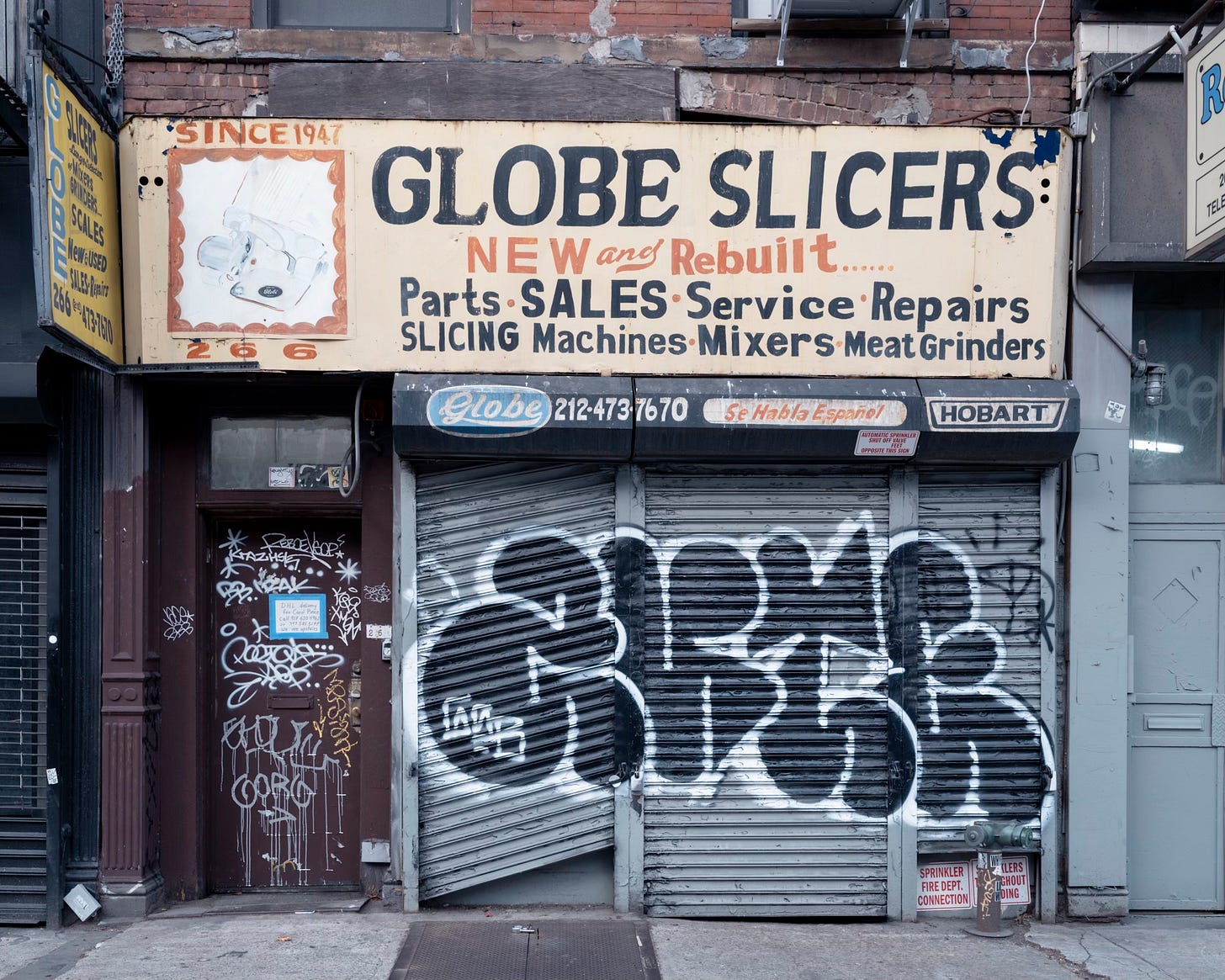

There are also a handful of restaurant supply stores that still sell the same industrial-sized mixers and meat slicers they’ve stocked since the 1950s.

And, amid the stacked white blocks of the New Museum and a Camper shoe store, the Bowery Mission continues to provide hot meals and shelter to those in need, as it has for more than 145 years.

BORDERS

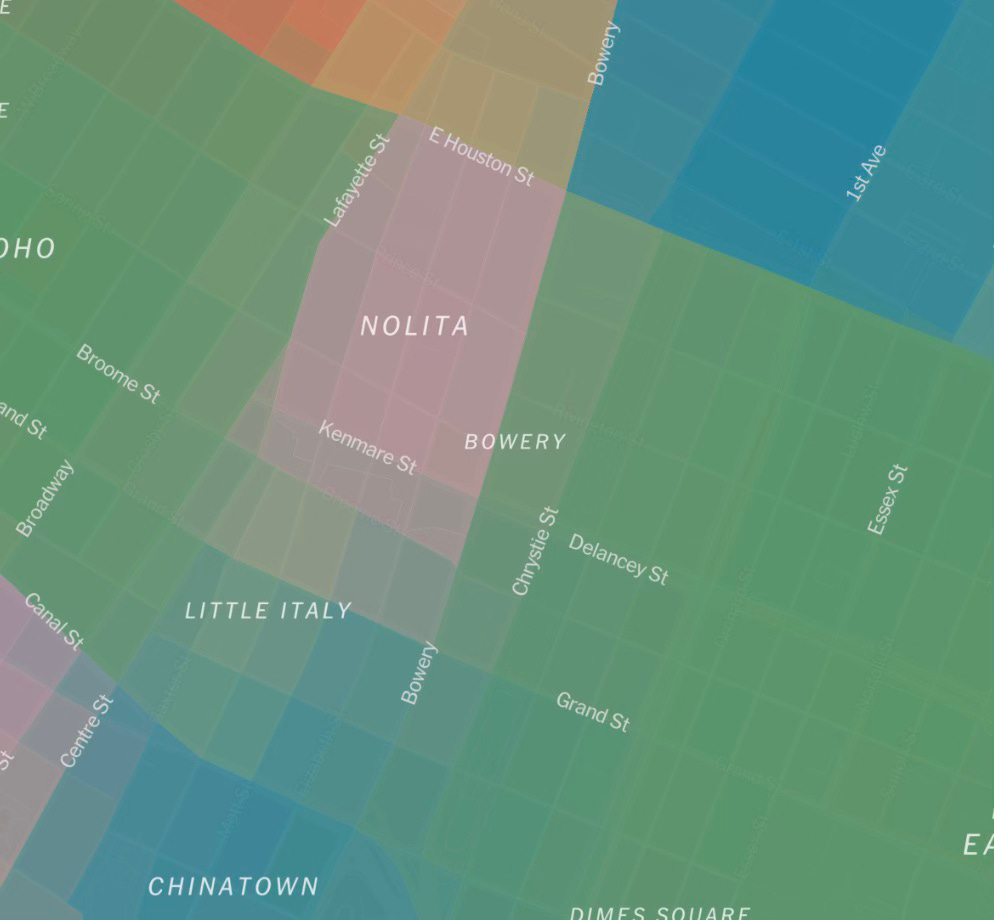

Google Maps shows the neighborhood’s borders extending eastward from its namesake avenue all the way to Allen Street, though, on the ground, that feels a bit generous. Chatham Square and Cooper Square serve as the Bowery’s southern and northern extremes.

The New York Times crowd-sourced Extremely Detailed Map of City Neighborhoods places the Bowery at the crossroads of at least six other neighborhoods: Chinatown, Nolita, Little Italy, the Lower East Side, and the East Village. With so many overlapping populations, the neighborhood doesn’t get its own color on the map—but at least it gets a name.

BOUWERIE

Bowery comes from the Dutch word for farm— bowerij or bouwerie. In the 17th century, when New York was still New Amsterdam, the Dutch West India Company established six large farms north of the city limits at Wall Street. Bowery Lane, following the contours of a Lenape footpath that stretched to the Harlem River, connected the farms to the population clustered at the southern tip of the island.

After the British takeover in 1664, former Dutch Director-General Peter Stuyvesant successfully petitioned to retire to his farm, Bouwerie No. 1, which he had purchased from the Dutch West India Company a few years earlier. He encouraged the settlement of a small village in the area.

By the early 1700s, during British rule, the farms gave way to estates that served as “theaters of refinement” for Manhattan’s landed gentry, who devoted themselves to aristocratic pursuits like rose gardening and horse racing. Lieutenant Governor James De Lancey had his own race course just off Bowery Lane.

Meanwhile, the southern portion of the Bowery, near one of the island’s most reliable sources of fresh water, became the city’s livestock district, full of cattle pens, slaughterhouses, and tanneries.

Perhaps the most famous establishment in the Bowery’s livestock district was the Bull’s Head Tavern, which years later, when the stench got to be too much, moved to Kip’s Bay. It was the de facto meeting spot for drovers and butchers, who would negotiate livestock prices under its low, smoke-stained ceilings while quaffing mugs of lukewarm ale.

One of the butchers, Henry Astor, had the bright idea of cutting out the middleman and would ride north to intercept the drovers before they had a chance to make it to the tavern. Astor soon became known for the high quality and low prices of his meat, and a year later, he used his profits to buy the Bull’s Head Tavern.

Famously, the Bull’s Head is where George Washington stopped before triumphantly entering the city on Evacuation Day.

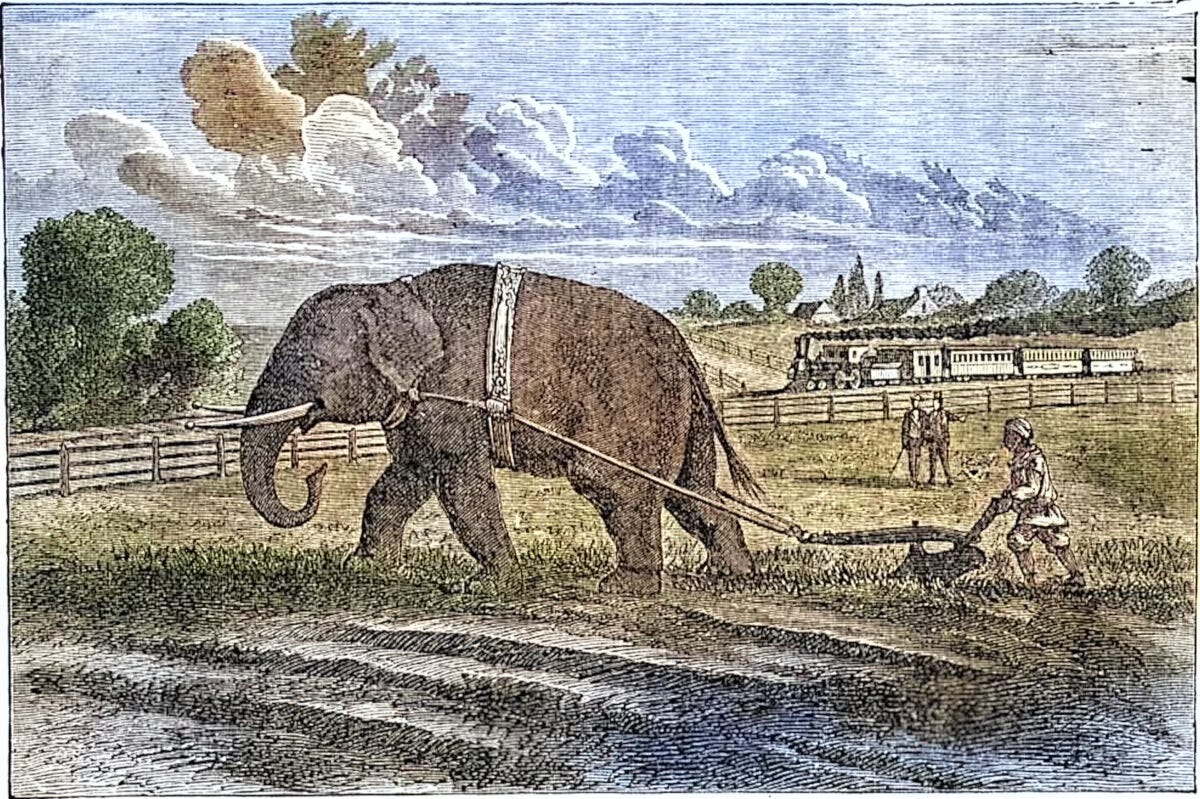

OLD BET

Perhaps less famously, the Bull’s Head was also where, in 1805, Hachaliah Bailey paid a ship captain $1000 to become the owner of the first (or maybe the second) African elephant to set foot in the United States. While his original intention was to use the beast to supersize his plow operation, the reaction the giant pachyderm elicited from the amazed onlookers on their journey back to Hachaliah’s farm in the town of Somers, NY, made him realize that he was sitting on a “gray gold mine.”

Hachaliah named his elephant Old Bet, and the pair would travel from town to town, charging curious locals 25 cents for a glimpse of the elephant. Since nobody pays for something they can see for free, Hachaliah and Old Bet traveled only at night, taking refuge in empty barns or behind tall fences until the big (paid) reveal.

When Bailey’s neighbors saw how lucrative the exotic animal industry could be, they too got in on the action, importing giraffes, zebras, and lions, pioneering the use of canvas tents to shelter their traveling menagerie. This made Somers, NY, the cradle of the American Circus.

Sadly, in 1816, Old Bet was shot in Alfred, Maine, by puritanical farmer and killjoy Daniel Davis, who was not happy with the elephant’s activities during the Sabbath.

Not to be deterred, Hachaliah bought a new elephant that he named Little Bet. Unfortunately, Little Bet met a similar fate to her predecessor and was gunned down after a performance in Chepachet, Rhode Island.

THE BOWERY THEATER

When the Bull’s Head moved uptown, Astor tore down the building and erected the New York Theater (later renamed the Bowery Theater) over the adjacent lot of the Bayard Slaughterhouse. With a capacity of 3,500 people, it was the largest theater in the United States at the time.

The place’s popularity took off when Thomas Hamblin began his tenure as manager, trading the high-class European drama on offer at the nearby Park Theatre in favor of a more populist mix of entertainment, including American melodrama, minstrel acts and, thanks in part to our friend Hachaliah, circus performances. Each spectacle was more elaborate than the previous, with the special effects and stage sets—erupting volcanoes, giant tanks of water to stage mock naval battles, troupes of trained dogs—taking precedence over the writing and acting.1

Another one of Hamblin’s innovations was the adoption of gas lighting, though the succession of six fires that ravaged the theater (1828, 1835, 1838, 1845, 1923, and 1929) called into question the wisdom, or at least the implementation, of that particular improvement.

BOWERY BOYS

Ironically, for a place so besieged by fire, a significant percentage of the theater’s clientele were volunteer firemen. One of the largest gangs in New York City at the time was the Bowery Boys (or B’hoys), and almost all of them, in addition to working as butchers or mechanics, were volunteer firemen.

There was no municipal fire department until after the Civil War, so groups of volunteers were the only bulwark against the seemingly constant conflagrations that engulfed the city. Often, rival bands of volunteer firefighters would spend more time fighting each other than the actual fire.

This clip from Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film Gangs of New York depicts one of those brawls and the common practice gangs engaged in of hiding fire hydrants under barrels to ensure only their brigade could use them.

The Bowery Boys, a conglomeration of several smaller gangs, were the Proud Boys of their time. They were staunchly nativistic, anti-Catholic, and anti-Irish. Ironically, one of the gang’s founders, Mike Walsh, was born in County Cork, Ireland, but Walsh, who would go on to serve in Congress, passed muster by virtue of being a Protestant.

The New York-born and bred ruffians usually held decent jobs and came from working-class backgrounds. They looked down on the less well-off immigrants descending upon “their” city and frequently battled with Irish gangs like the Chichesters, the Forty Thieves, and the Dead Rabbits, who controlled the notorious Five Points just to the south.

Their hatred of immigrants was matched only by their love of theater. The Bowery Boys couldn’t get enough of the “blood and thunder” fare on offer at the Bowery Theater, especially when the productions began featuring actors portraying characters who looked and acted like them. The actors wore the classic Bowery Boy attire, with red flannel shirts and shining stovepipe hats perched over long, glistening sidelocks slicked in place with liberal amounts of bear grease or soap.

When these actors launched into the trademark Bowery Boy patois, “somewhere between a falsetto and a growl,” the crowd went berserk.

[a] black silk hat, smoothly brushed, sitting precisely upon the top of his head, hair well oiled, and lying closely to the skin, long in front, short behind, cravat a-la sailor, with the shirt collar turned over it, vest of fancy silk, large flowers, black frock coat, no jewelry, except in a few instances, where the insignia of the engine company to which the wearer belongs, as a breastpin, black pants, one or two years behind the fashion, heavy boots, and a cigar about half smoked, in the left corner of his mouth, as nearly perpendicular as it is possible to be got. He has a peculiar swing, not exactly a swagger, to his walk, but a swing, which nobody but a Bowery boy can imitate2

Over the next several decades, the programming at the Bowery Theater evolved, reflecting the shifting demographics of the neighborhood and the city as a whole.

First, with the influence of the Bowery Boys waning, the theater pivoted to putting on mostly Irish productions. Then, in 1879, to serve a burgeoning German population, the Bowery was rebranded the Thalia Theatre and concentrated on German plays and musicals. In 1891, Yiddish theatre helped resuscitate the floundering venue. Soon after came the vaudeville productions, geared first towards Italian and later Chinese clientele. By the time "Fay's Bowery Theatre” burned down in 1928, the neighborhood’s glory years were far behind it.

THE LAST STOP ON THE WAY DOWN

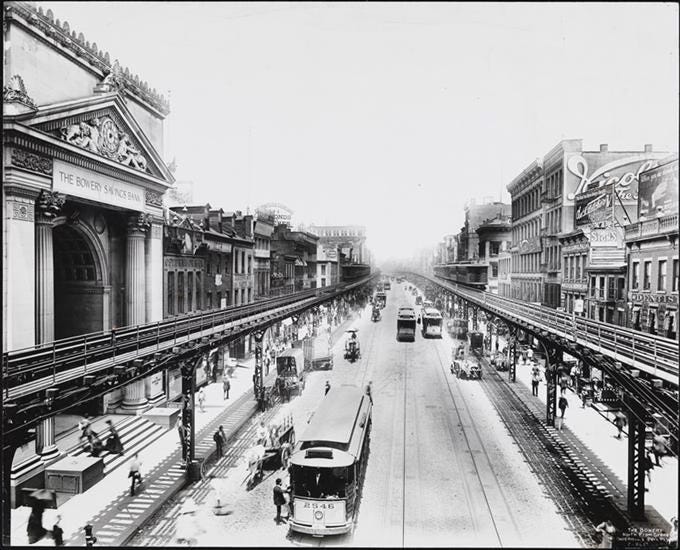

The arrival of the Third Avenue Elevated rail, casting its long shadows over the Bowery from 1878-1955, cemented the neighborhood’s reputation as a place best avoided. The Bowery was, in the words of Lucy Sante, “the last stop on the way down.” In reality, the El only accelerated the Bowery’s decline, a trajectory that had started years before.

Lucy Sante again:

the Bowery always possessed the greatest number of groggeries, flophouses, clip joints, brothels, fire sales, rigged auctions, pawnbrokers, dime museums, shooting galleries, dime-a-dance establishments, fortune-telling salons, lottery agencies, thieves' markets, and tattoo parlors, as well as theaters of the second, third, fifth, and tenth rank.

To help ease congestion, a new set of express tracks was constructed between the existing ones, further obscuring the illicit activities of the pickpockets, prostitutes, and peddlers who roamed the ash and cinder-filled streets below. Opium dens, brothels, and dive bars with evocative names like the Plague, the Hell Hole, and the Fleabag did a brisk business.

Some bars, called barrelhouses, dispensed with glassware entirely, offering any patron willing to pony up 3 cents the chance to drink from rubber tubes connected to barrels of beer until they ran out of breath. The art of circular breathing flourished.

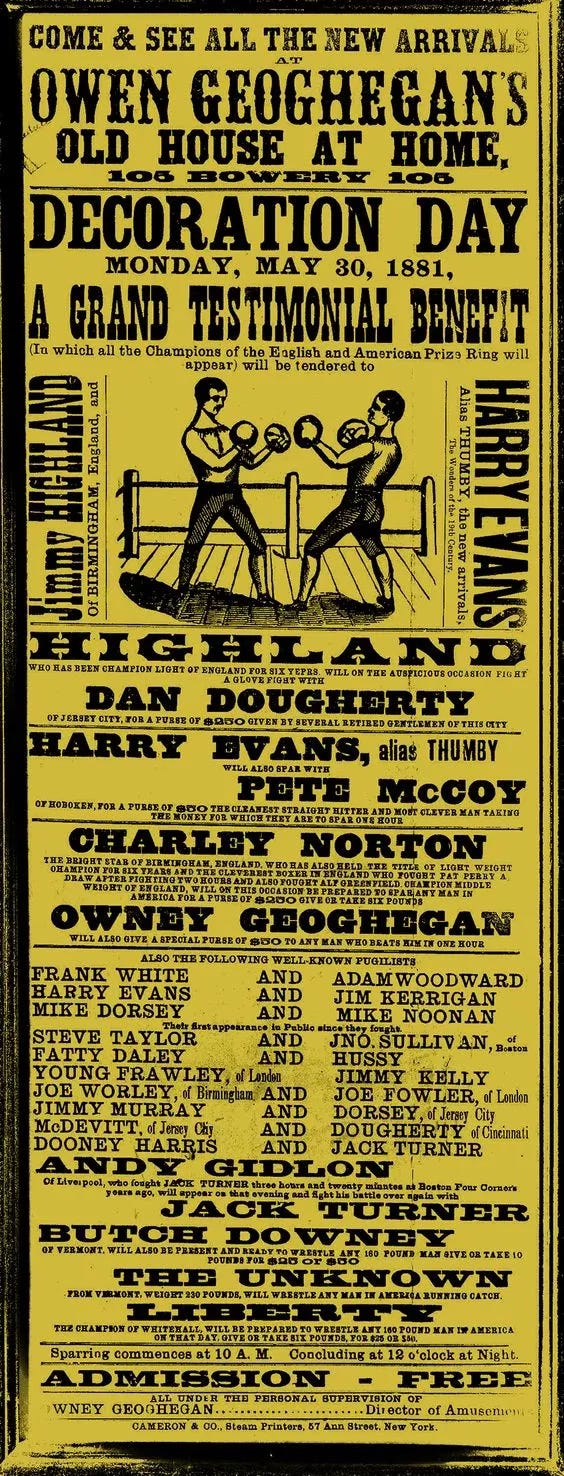

Owney Geoghegan’s Saloon, at 105 Bowery, The Old House at Home, featured two 12-foot bare-knuckled boxing rings, In addition to watching fights, patrons were encouraged to participate in them, drunkenly beating each other to a pulp while pickpockets practiced their arts on the cheering crowds.

It was also a popular meeting spot for the city’s ersatz handicapped population, who used a variety of props to increase their potential panhandling earnings. Every night, they would stash their crutches, casts, and prosthetics in lockers in the back before spending their day’s profits at the bar. Rentals were available too.

Whatever you needed for a convincing sympathy-inducing appearance was available: crutches, casts, bandages, and even children could be hired by the day or week.3

Perhaps the most notorious establishment of them all was John McGurk’s bar and brothel at 295 Bowery. McGurk, a true believer in the adage, “any publicity is good publicity,” renamed his bar “McGurk’s Suicide Hall” after several prostitutes attempted suicide on the premises.

SKID ROW

If construction of the El hastened the Bowery’s decline, the passage of the Volstead Act, followed soon after by the Great Depression, dealt the final blow. By the early 20th century, the Bowery Boys had vanished, replaced by the “Bowery Bums.”

The fact remains that for two centuries, the Bowery was the place where everything happened, and then suddenly, it became the place where nothing happened at all.4

The Bowery Mission, founded in 1879, was the first organization to address the food and housing needs of the transient population flooding the neighborhood. Although it has moved several times in its 145-year history, including a brief stint in Oweny Geoghegan’s former saloon, the Mission still serves the neighborhood today.

By the 1920s, the Mission, the YMCA, and the dozens of cheap hotels and flophouses in the Bowery were said to have been home to tens, if not hundreds of thousands, of homeless men.

An article from a 1924 issue of the New York Times Magazines, written as an ode to the Bowery of old, describes the atmosphere in one of the neighborhood’s flophouses.

upstairs it is dingy and gloomy, with a heavy, potatoey smell in the air. A dim night-light burning in the halls, a deserted "reading room," a man with a pale, nocturnal visage behind a desk, and then rows and rows of semi-partitioned rooms, men snoring. The muttering and the roar of traffic outside. You have to be out by 8 A.M. It's the rule.

On the Bowery, a quasi-documentary film directed by Lionel Rogosin portrays life on Skid Row in the 1950s.

5 SPOT TO CBGB

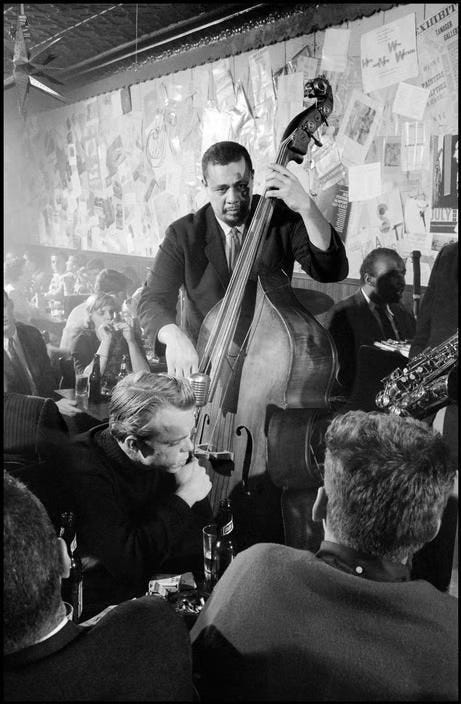

The demolition of the Third Avenue El in 1955 marked the beginning of a slow transformation for the Bowery. A year later, the Five Spot Café opened at 5 Cooper Square, signaling the neighborhood’s reemergence as a cultural hub.

The Five Spot became a gathering place for writers and artists like Helen Frankenthaler, Jack Kerouac, Frank O’Hara, and Amiri Baraka, who came to hear jazz legends like Thelonious Monk, Cecil Taylor, and Ornette Coleman.

I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

from Frank O'Hara's "The Day Lady Died,"

Though the Five Spot moved after just six years, it was a bellwether of the neighborhood's changing fortunes. Artists had already begun to move in, taking advantage of the cheap rents and large spaces. Mark Rothko, William Burroughs, Robert Frank, Nan Goldin, and Debbie Harry were just a few artists who called the Bowery home.

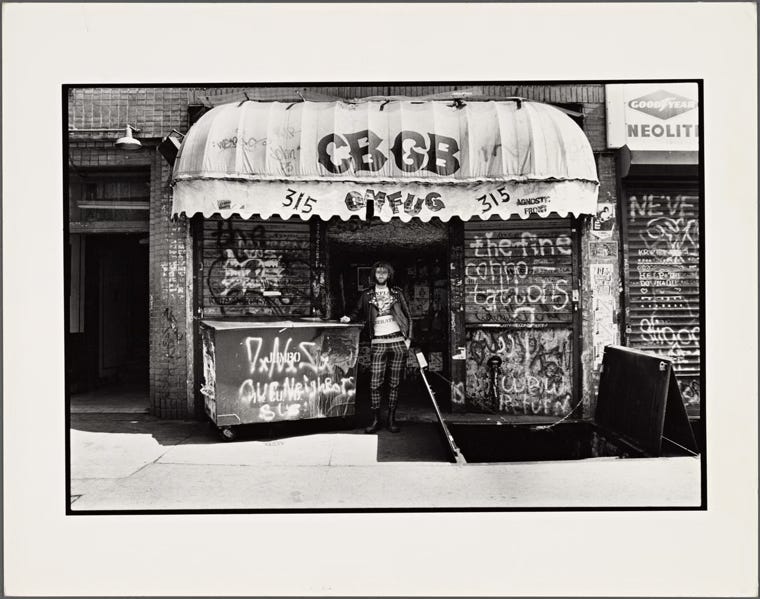

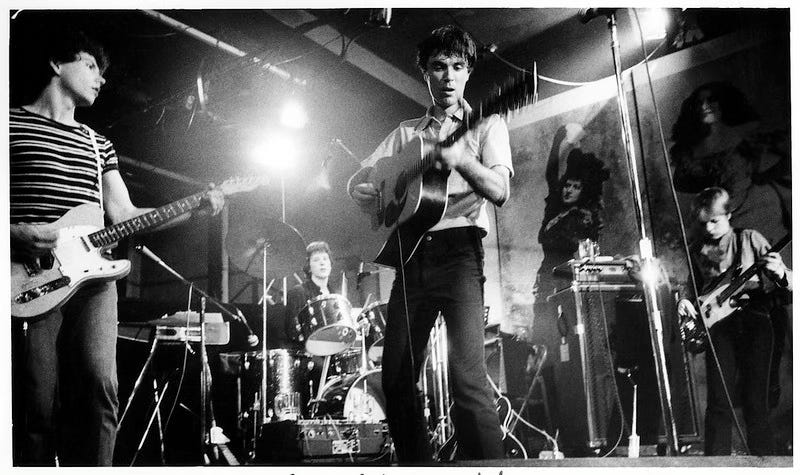

The Bowery’s punk rock counterpoint to the Five Spot was CBGB, or, more formally, CBGB & OMFUG (an acronym for "Country, Bluegrass, Blues, and Other Music For Uplifting Gourmandizers"). Bands like The Ramones, Television, the Talking Heads, Blondie, and Patti Smith got their start at the club.

In 2006, after getting into a dispute with their landlord over unpaid rent, CBGB shut down. Today, the building that once hosted Bad Brains, The Damned, and Agnostic Front is home to designer John Varvatos’s upscale menswear boutique, where you can buy a CBGB t-shirt for $100.

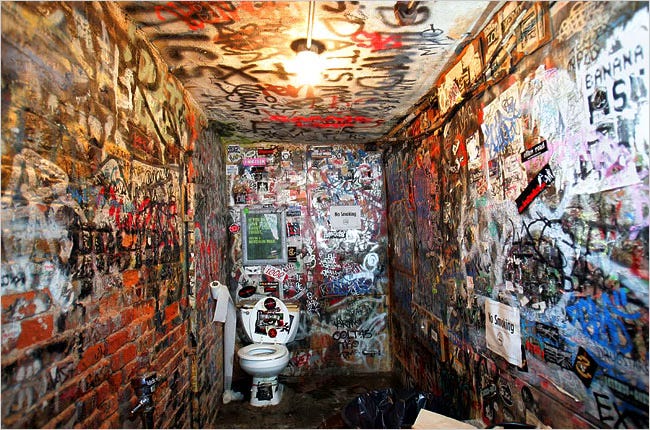

Not surprisingly, the CBGB Lounge and Bar, which opened at the Newark airport in 2016, has served its last plate of disco fries. Attracting customers to a restaurant in an airport inspired by a place known for what David Byrne called its “legendarily nasty” toilets was always going to be an uphill battle.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

I’m still having technical difficulties with the field recording setup, so there is no audio recording this week. Sorry to the handful of you who listen to these!

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

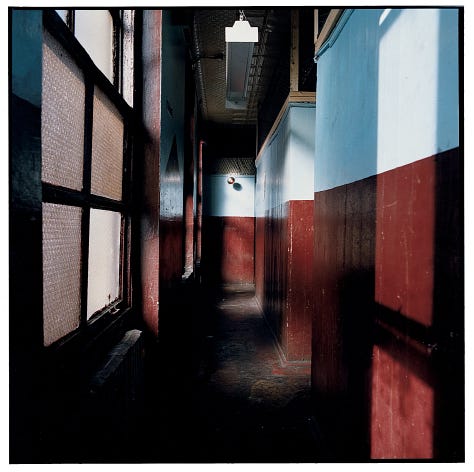

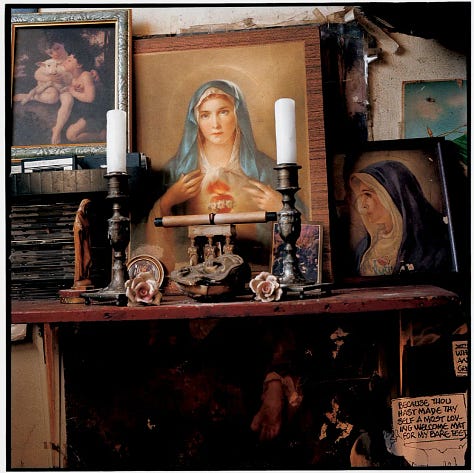

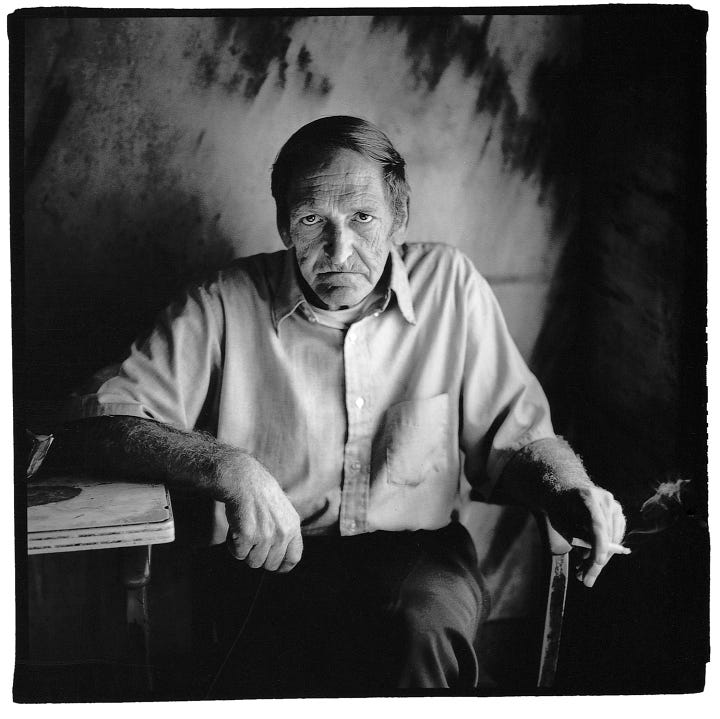

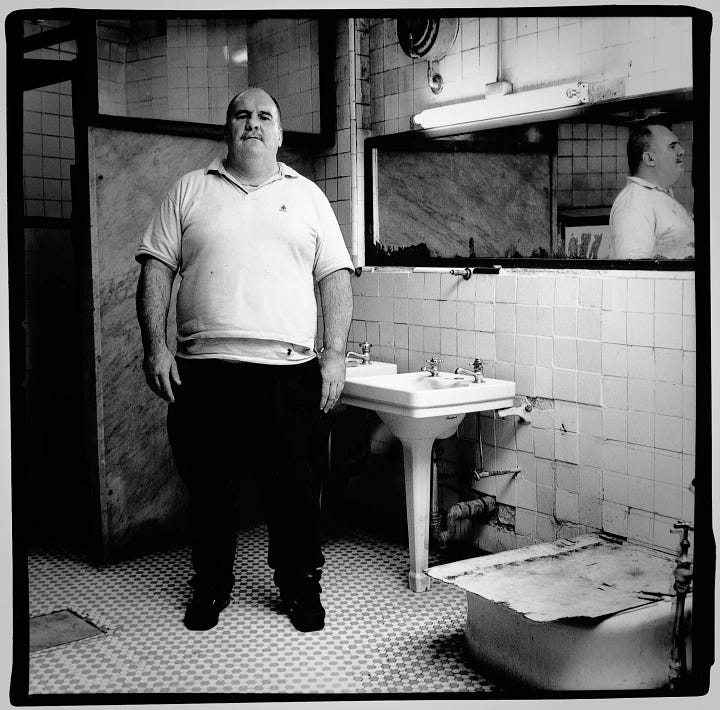

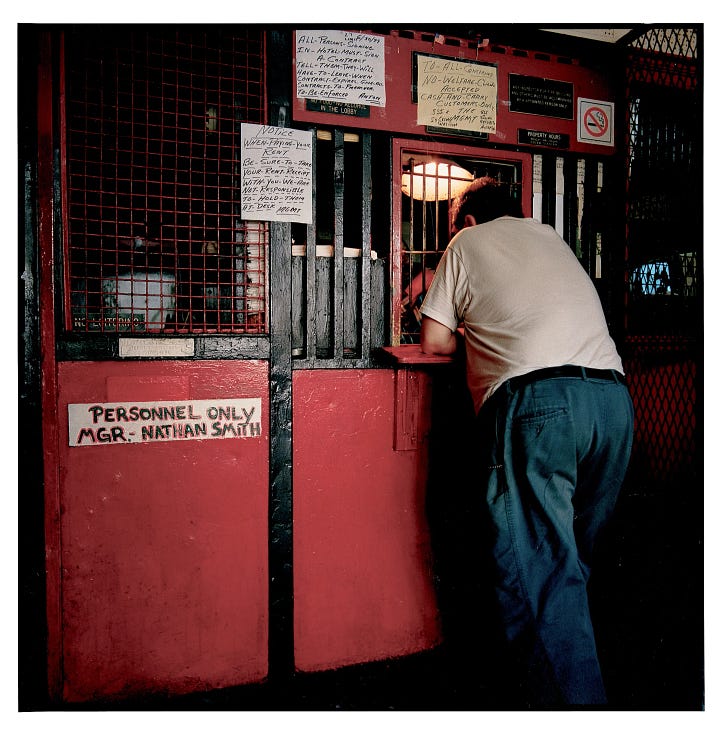

Photographer Harvey Wang, who studied visual arts and anthropology at Purchase College, has published six books of photography and has made several movies, including films on photographers Sid Kaplan and Milton Rogovin.

“The Bowery, the world’s most infamous skid row, has long fascinated me. Barber shops, employment agencies, liquor stores, tattoo parlors, and cheap restaurants once lined this New York City street. During its heyday, between 25,000 and 75,000 men slept on the Bowery each night. Today, gentrification has transformed the 16 blocks that make up the Bowery, just like it’s remade much of New York City. All that remains of the old Bowery are a mission, a single liquor store, and seven “lodging houses,” which are home to less than 1,000 men.”

This work is from Wang’s project that turned into the book Flophouse: Life on the Bowery Wang made with David Isay and Stacy Abramson.

NOTES

In the 1970s, photographer Jay Maisel figured out the best way to make millions of dollars as a photographer: real estate. In 1966, Maisel bought the six-story, 72-room, 35,000-square-foot former Germania Bank building for $102,000. In 2014, in what was considered the greatest real estate return on investment in Manhattan’s history since Minuit paid the Lenape $26 for the whole island, Maisel sold his private residence for a cool $55 million.

Maisel and his home are the subjects of Jay Myself, a film by Steven Wilkes, his former assistant and fellow photographer.

Recommended Reading:

Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York - Lucy Sante

The Bowery: The Strange History of New York's Oldest Street Stephen Paul DeVillo

Devil's Mile: The Rich, Gritty History of the Bowery Alice Sparberg Alexiou

Mazie Gordon, Queen of the Bowery Joseph Mitchell

Martha Rosler’s The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems is part of Rosler’s “ongoing exploration of urban life and the representation of poor and disenfranchised groups. The work consists of 24 framed panels, each juxtaposing a photograph of a loosely covered typewritten page with a photograph of a storefront, entrance, or façade.”

That was a long one, and there was so much I had to leave out. This will be the last dispatch of the year besides my usual bonus Monday newsletter. Thanks, as always, for your support and attention!

Sante, Lucy. Low Life : Lures and Snares of Old New York. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

Anbinder, Tyler (2001). Five Points: The 19th-century New York City Neighborhood that Invented Tap. New York, NY: The Free Press.

DeVil, Stephen Paul. The Bowery: The Strange History of New York's Oldest Street (p. 144). Skyhorse. Kindle Edition

Coates, Robert. “THE STREET THAT DIED YOUNG; the Bowery, Where for Two Centuries Everything Happened, and Now Nothing Happens.” Nytimes.com, 14 Sept. 1924, timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/09/14/101611350.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0. Accessed 20 Dec. 2024.

Thank you for taking me on such a wonderful tour through history with my morning coffee. As annoying as the pricey and sterile glass towers are, the old Bowery refuses to disappear entirely.

Beautiful. I will walk again this neighborhood and open this post again. So much to look into…. Whenever I am in NY I pass by 11 Bleeker St if the option comes up. June Leaf is still on the buzzer. They never sold the house before they died. You can still see some of her sculptures in the window of the studio.