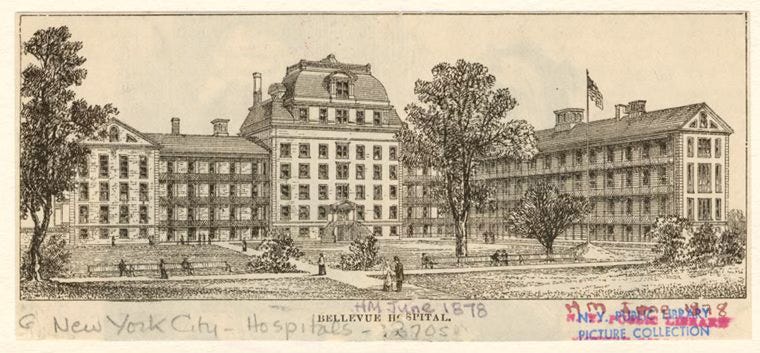

Fittingly, after what has been a tumultuous week, a good portion of today’s newsletter is devoted to Bellevue Hospital, the city institution that is synonymous with madness. For years, if you were a New Yorker suffering from delirium tremens, schizophrenic delusions, or nervous breakdowns, there was a very good chance you would end up in Bellevue, the “endpoint of an urban nightmare” in the city’s collective unconscious.

Bellevue is the most recognizable landmark in the Manhattan neighborhood of Kips Bay, which runs from East 23rd St to East 34th St, between Lexington Ave and the East River. The neighborhood was the site of a major British invasion, once home to the city’s largest cattle farm, and served as the launching point for the underground cross-country race that inspired three terrible Burt Reynolds films.

Its name comes from the mid-17th century estate owned by Dutch merchant Jacobus Henderson Kip.

BATTLE OF KIPS BAY

In September 1776, two weeks after Washington’s troops had made a hasty retreat from Brooklyn, five British warships sailed into the East River and anchored offshore from Kips Bay. Meanwhile, 4,000 British and German troops jammed into a flotilla of flatboats at Newtown Creek. They sailed towards shore with “the strains of exciting music, and the peals of thundering guns, the tall ships vomiting flames and murderous shot” under “rolling volleys of smoke.” The sight of the incoming Redcoats and the barrage of cannonballs was enough to send the 450 untrained militiamen guarding the shore, armed with nothing more than sharpened sticks, running for their lives.

The demons of fear and disorder seemed to take full possession of all and everything on that day.

When they saw their fellow Patriots sprinting towards them, the regiments positioned further inland dropped their weapons and started running away, too. At the same time, General Washington was heading down from Harlem towards the sounds of battle. With “great surprize and Mortification” he saw his terrified troops running in the opposite direction. An incensed Washington admonished the fleeing men, demanding that they stay and fight and even hitting some of them with his riding crop to get his point across. Not surprisingly, this tactic did not inspire the soldiers to change their minds, and eventually, Washington, too, had to turn back after getting within 50 yards of the British troops.

After stopping for tea in Murray Hill, the British took control of Manhattan, where they stayed for the next seven years.

When the British finally withdrew in 1783, Washington made his way back to the city he had been forced to flee. In his triumphant return, Washington and his entourage convened at the Bull’s Head Tavern before making “their official entrance into the city proper.”1

The tavern, which was at the then northern edge of the city (around the entrance to the future Manhattan Bridge), was a favorite watering hole of the cattle drivers and butchers who circulated through the slaughterhouses, stockyards, and tanneries that surrounded it.

In 1813, with the city limits slowly creeping northwards and the smells and noise of the endless bovine processions deemed uncivilized, the tavern and all the cattle operations were encouraged to move. They decamped for the “country,” which would today be around 23rd St and Second Ave.

The area soon became known as Bull's Head Village, and for over twenty years, it served as “the great cattle market of the city.” The tavern had the area’s only bank and inn, and all business transactions were handled there. It was a waypoint for the farmers and breeders who would bring their cattle (from as far away as Ohio) to sell to local residents.

A butcher who acquired an exceptionally fine cow would then parade it through the streets, preceded by a band and followed by fellow butchers in aprons and shirtsleeves, stopping before homes of wealthy customers, who were expected to step out and order part of the animal.2

With all the meat cleaving and ale swigging going on, there is no doubt that some of the patrons of the Bull’s Head found the hospital, being built just to the east, a welcome amenity.

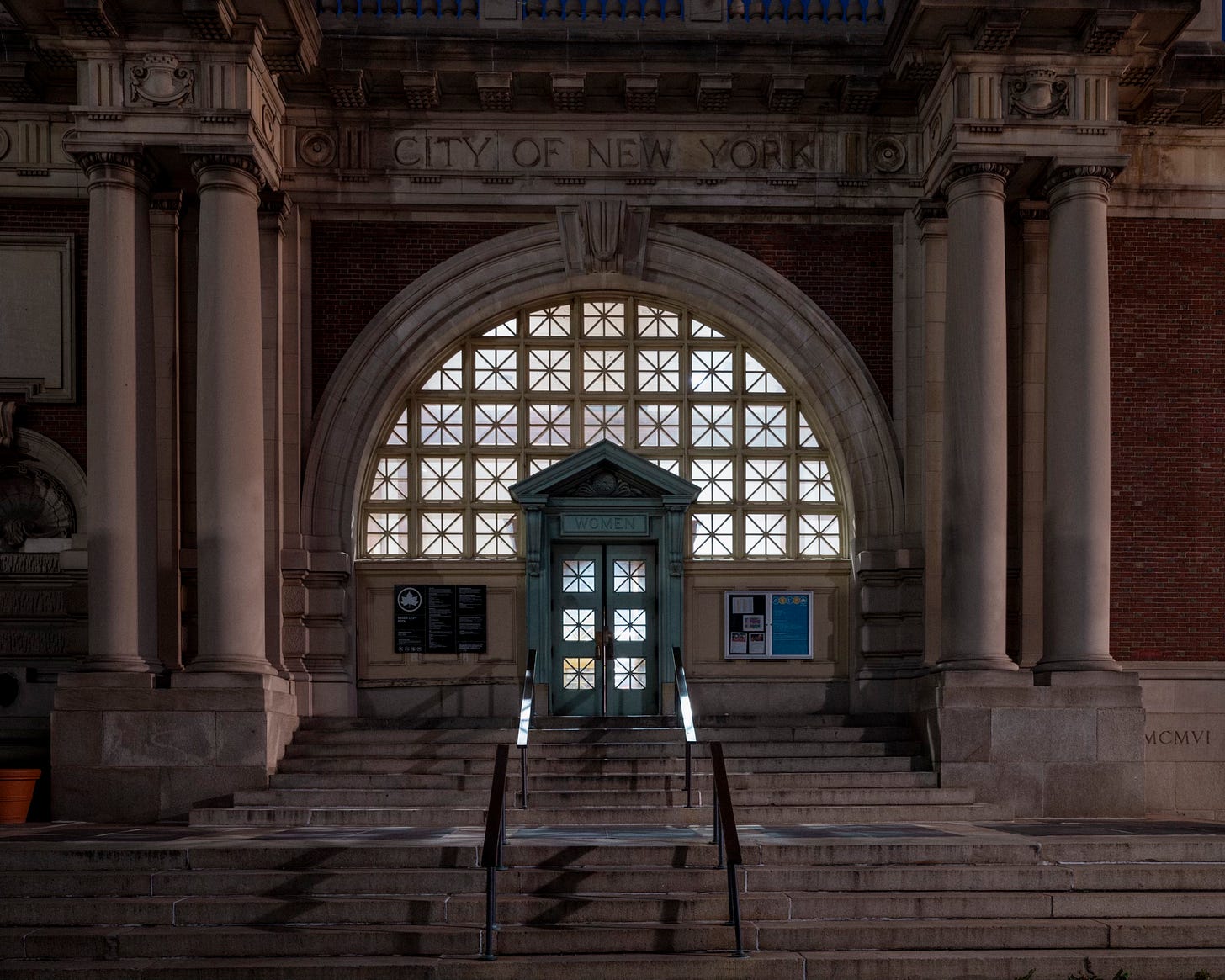

BELLEVUE

Bellevue was founded in 1736 as the Almshouse Hospital on the site of what is now City Hall, making it the oldest public hospital in the country.

Like the cattle industry, the hospital eventually moved north, building a new facility on the former Bel-Vue estate on the banks of the East River in 1816. When it opened, it was the city’s largest and most expensive project, containing a pesthouse, an almshouse, an orphanage, a lunatic asylum, a prison, and an infirmary. The hospital was (and still is) a place to care for those who couldn’t otherwise afford it, treating waves of newly arrived immigrants and the city’s indigent population. Every major epidemic—cholera, tuberculosis, yellow fever—saw a new influx of patients who couldn't afford the private hospitals uptown. Mortality rates were high. Harper’s magazine called Bellevue a place for the “poorest of the poor, the dregs of society, the semi-criminal, starving, unwelcome class, who suffer and die unrecognized.”

Still, the hospital had some of the best doctors in the country and was responsible for an enormous number of medical innovations. Bellevue had the country’s first morgue, maternity ward, and nursing school.

It had the country’s first ambulance corps, which consisted of a fleet of horse-drawn stage coaches equipped with stretchers, whiskey, bandages, a stomach pump, and a straitjacket for those of “a demonstrative disposition.”

The hospital also had the country's first medical photography department, emergency service, and pathology department. It performed the first cesarean section and the first successful operation of the abdomen for a pistol shot. Less successful was its pioneering use of tobacco in the treatment of cholera. When doctors injected a vial of tobacco juice, warmed to 112 degrees, into the arm of an infected woman, things did not end well.

Bellevue was where Alexander Hamilton was taken after he was shot by Aaron Burr. It was the first place New Yorkers would go after catastrophes like the Civil War Draft Riots, the General Slocum disaster, and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire to find their loved ones.

The hospital has treated more AIDS patients than any hospital in the country and treated the city’s first and only known Ebola patient.

It also had the country’s first psychiatric ward, a place whose notoriety almost entirely eclipses the numerous accomplishments of the rest of the hospital. In his fantastic history of Bellevue, David Oshinsky describes the psychiatric hospital as a “revolving door for legions of writers, artists, and musicians in various states of distress.”

The best minds of my generation … talked continuously seventy hours from park to pad to bar to Bellevue to museum to the Brooklyn Bridge.

Allen Ginsberg

Writers like Allen Ginsberg, Eugene O’Neill, and Sylvia Plath spent time at Bellevue. William Burroughs went there after cutting off part of his pinky with poultry shears in an unsuccessful attempt to impress a man.

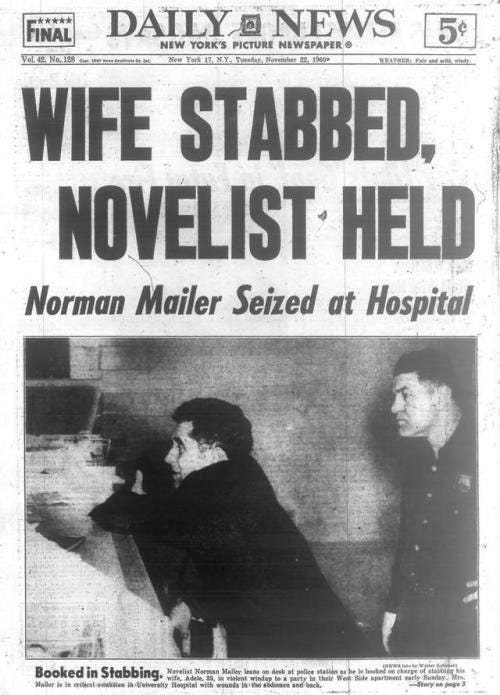

After a long night celebrating his recently declared candidacy for mayor, Norman Mailer stabbed his wife, Adele Morales, in the abdomen and back with a penknife. Morales supposedly triggered the incident by telling him he would never be as good as Dostoyevsky. He spent 17 days in Bellevue.

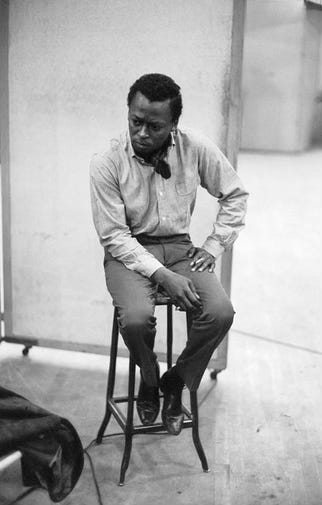

Jazz musicians Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and Charles Mingus also all spent time at the hospital. Mingus, suffering from depression, checked himself into Bellevue, though some accounts say it was to get out of a contract he had signed with a mafia-connected concert promoter. In his autobiography, Mingus wrote about his time in lockdown playing chess with an 18-year-old Bobby Fischer. When Mingus was released, he wrote “Lock'em up (Hellview of Bellevue),” an appropriately manic romp complete with dissonant horn squawks and a man screaming.

In 1980, Mark David Champman, wearing a bulletproof vest and surrounded by armed officers, was brought to Bellevue after shooting John Lennon.

Bellevue’s psychiatric ward shut down in 1984 became a men's homeless shelter in 1998. Recent plans to convert the building into a hotel have failed to come to fruition.

THE CHURCH

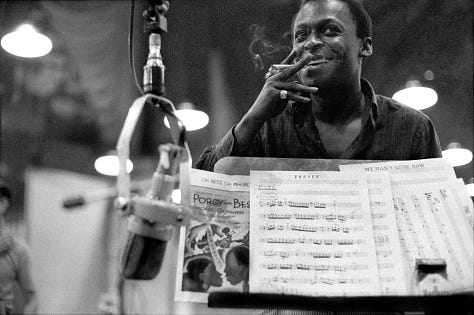

Just before Mingus checked himself into Bellevue, he recorded one of the greatest jazz records of all time, Mingus Ah Um. He made the record just a few blocks from Bellevue.

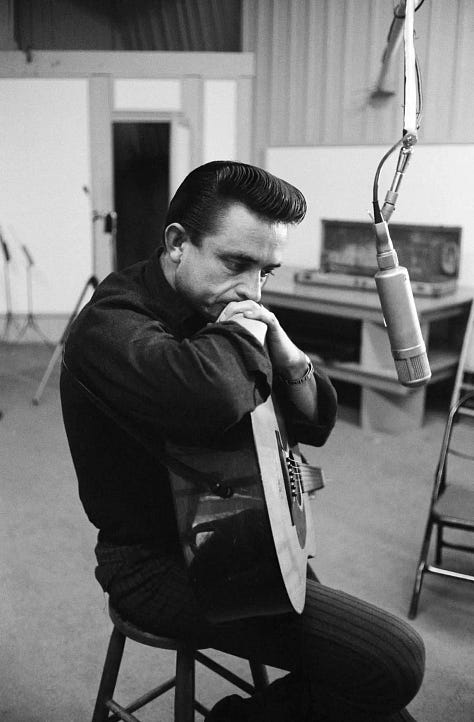

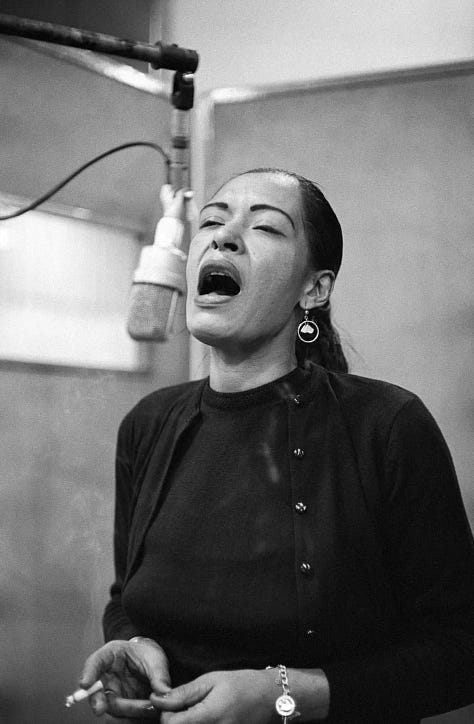

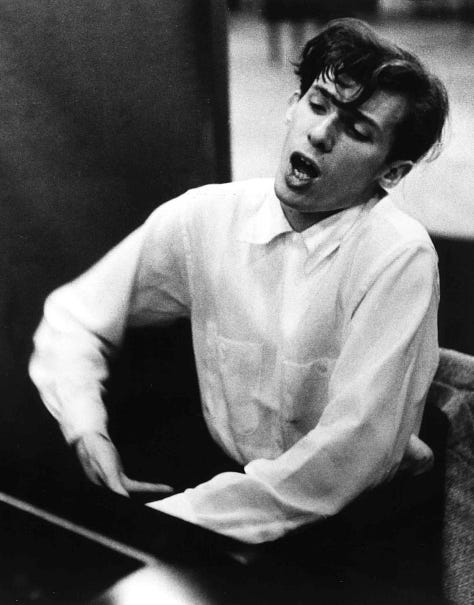

For a certain subset of the population (and I put myself in that subset), the unremarkable 10-story residential apartment building at 207 East 30th Street called "The Wilshire" sits on sacred ground. Prior to the apartment building’s construction in 1985, the plot was occupied by the 30th Street Studio, also known as "The Church," a recording studio responsible for several of the most influential recordings ever produced.

The Adams-Parkhurst Memorial Presbyterian Church was built in 1875. It had been vacant for several years when Columbia Records took it over in 1948, transforming the space — 97 feet long by 55 feet wide, with a 50-foot-high ceiling—into what many consider the world’s greatest sounding studio.

Miles Davis recorded what is arguably his most essential run of albums between 1957 and 1970. Miles Ahead, Milestones, Porgy and Bess, Kind of Blue, Sketches of Spain, Someday My Prince Will Come, Seven Steps to Heaven, Miles Smiles, Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Filles de Kilimanjaro, In a Silent Way, and Bitches Brew were all recorded at the Church.

Aretha Franklin recorded her debut there.

Terry Riley’s In C, Glenn Gould’s The Goldberg Variations, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out were all recorded there as well.

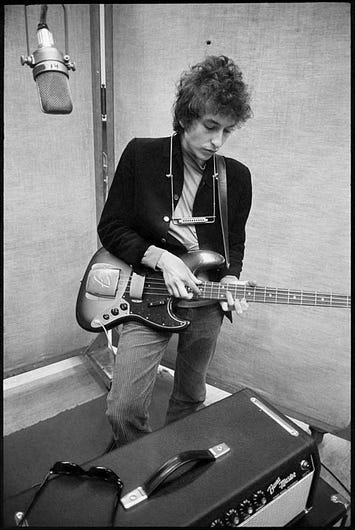

Thelonius Monk, Mahalia Jackson, Bob Dylan, and hundreds more all recorded at the studio. If it wasn’t the greatest studio in the world, it certainly was responsible for some of the greatest music of the 20th century.

Though Columbia could have bought the building for $250,000 in 1981, the high energy bills and a clause prohibiting noise after 11 p.m. made them walk away. The building was demolished in 1982, and today, we have this.

Here is a playlist of music recorded at The Church, plus two bonus Bellevue-specific tracks by Mingus and Lead Belly, who wrote Bellevue Hospital Blues just days before he died.

CANNONBALL RUN

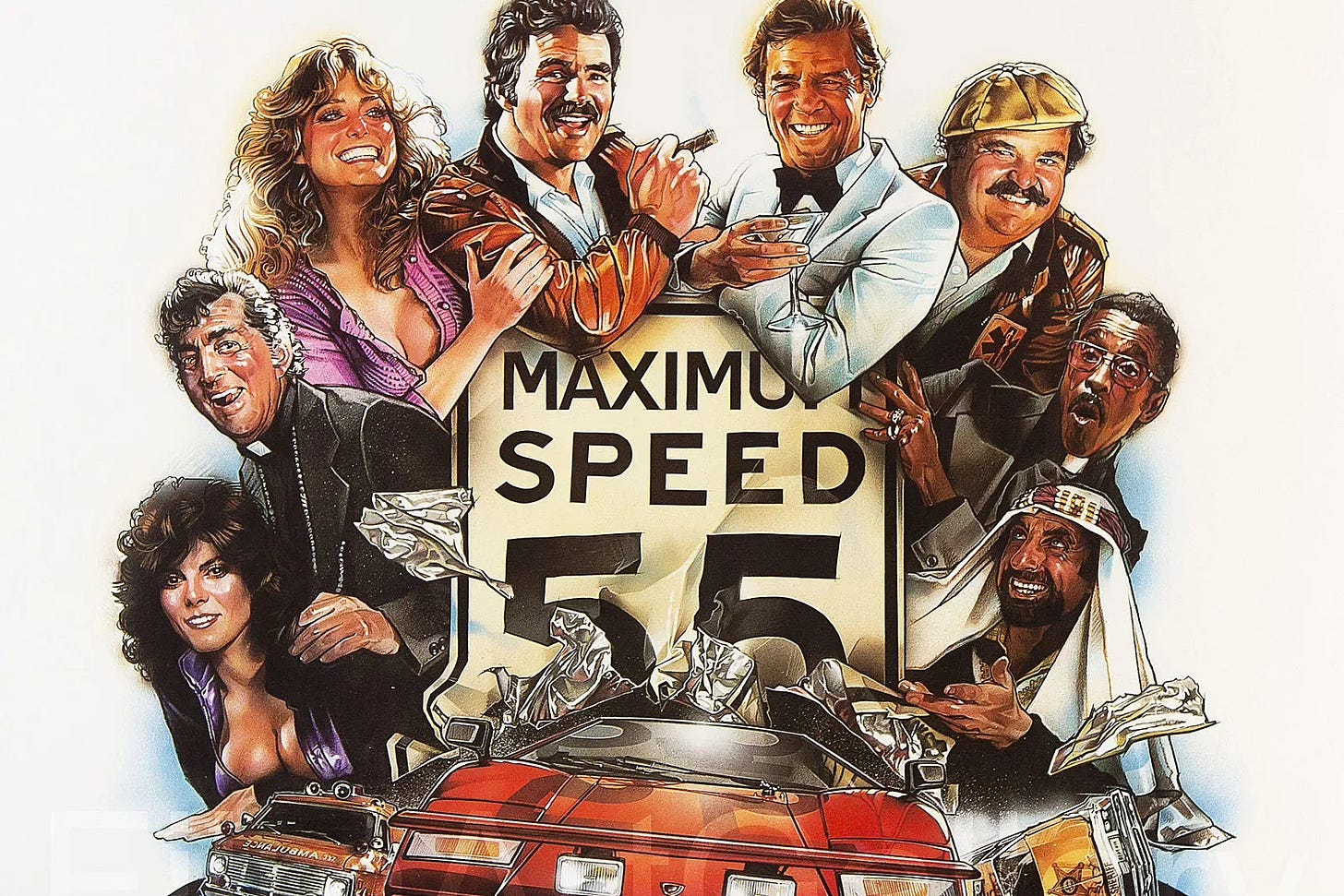

Until this week, I had no idea that Cannonball Run, the 1981 madcap cross-country car race movie Roger Ebert called “an abdication of artistic responsibility at the lowest possible level of ambition,” was based on a true story, one that started in a garage in Kips Bay.

On November 15, 1971, six cars left the Red Ball Garage on East 31st St and began a race that would end nearly 3,000 later at the Portofino Hotel in Redondo Beach, California. The race, dubbed the Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash, was conceived of by Brock Yates and Steve Smith from Car and Driver Magazine as a protest to the Federal 55 mph speed limit. The winning car made the trip in 35 hours and 54 minutes. The underground race was run four more times—again in 1971, 1972, 1975, and 1979—before Yates stopped sanctioning it, saying, “sooner or later that somebody was going to get killed.”

The end of the official iteration of the unofficial race didn’t put an end to people trying to break the record.

To avoid detection, racers have employed radar jamming equipment, decoy cars, and even planes to monitor the interstate for state troopers. In one case, a team of racers, both physicians, kept a cooler with a pair of pig eyeballs inside their Jaguar. In the event they got pulled over, they would show the porcine eyeballs to the trooper, claiming they were speeding to “save a child’s sight, officer.”

The current record was set in 2020 in an astonishing 25 hours and 39 minutes, at an average speed of over 110 mph.

SIGHTS

This week’s audio has some Baby Gronk references, lots of helicopter noise and a bit of birdsong from the hidden Bellevue Sobriety Garden.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Besides his work in the 30th street studio, photographer Don Hunstein, who worked at Columbia from 1956 to 1979, shot several record covers, including his most well-known image used on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. According to NYT critic Janet Maslin, the cover "inspired countless young men to hunch their shoulders, look distant, and let the girl do the clinging.”

More of Hunstein’s work.

NOTES

32 Hours 7 Minutes is a documentary film about the the 1983 attempt to break the Cannonball Record. Not sure where to watch the whole thing, but the trailer looks good.

During World War II, Bristol, England, was a major port for ships bringing weapons and other supplies from the US. After unloading all their cargo, the ships had no ballast for their return trip, so the citizens of Bristol filled the boats with the destroyed remnants of their city. When the ships returned to New York, they dumped the ballast in Kips Bay, the exact spot where the British came ashore some 160 years earlier. Today, that infill, from 23rd to 34th Street, is known as Bristol Basin and sits underneath the FDR and the towers of Waterside Plaza

.

Speaking of Roger Ebert, this behind-the-scenes compilation of Siskel and Ebert recording promos in 1987 gets 👍👍.

Until this week, Grover Cleveland was the only US President to serve nonconsecutive terms. On July 1, 1893, surgeons from Bellevue, on a private yacht in the East River, performed a clandestine and ultimately successful surgery to remove a malignant mass from the roof of his mouth.

A short Glenn Gould documentary that features footage from “The Church."

For a place that was once full of slaughterhouses and hoof-boiling operations, there are a surprising number of vegetarian and vegan-friendly restaurants in Kips Bay. Candle Cafe and Coletta are both good options.

Besides Bellevue, Kalustyan’s, the 80-year-old food emporium which carries over 10,000 food products from over 80 countries, is probably Kips Bay's most famous institution. It’s the only place in the city where you can find Indian Wrinkled Chilis, strawberry sugar, or a ten-pound bag of blue cheese powder all under the same roof. The building at 123 Lexington was once owned by Chester A. Arthur, who was sworn in as president there in 1881 after James Garfield’s assassination.

https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/14/unearthed-a-possible-stop-along-the-revolution/

Burrows, E. G., & Wallace, M. (1999). Gotham: A history of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press.

Loved this one! I really hope you compile all of these into a book one day.

The Church is up there with Motown's Hitsville studio, Stax's McLemore Avenue pad in Memphis, Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, and the FAME operation in Muscle Shoals, Alabama as one of the most influential recording studios of them all.