Though Brooklyn’s Red Hook is technically a peninsula, surrounded by the waters of Upper New York Bay and the Gowanus Canal, its relative isolation makes it feel more like an island, a perception reinforced by the ever present brackish tang of sea air.

Once one of the busiest ports in the world, Red Hook began a slow decline after the construction of the Gowanus Expressway in 1941, a downturn that coincided with the global shipping industry’s shift toward containerization. A decade later the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel effectively severed the neighborhood from the rest of South Brooklyn just as its economy was beginning to unravel.

Those same infrastructure projects, along with limited transit options, also served as a bulwark against the wave of gentrification that swept through adjacent neighborhoods like Carroll Gardens and Park Slope.

Still, this is New York City, and if recent construction booms on the edges of other neighborhoods like Greenpoint, Long Island City, and Williamsburg are any indication, this quiet corner of Brooklyn may soon be unrecognizable.

RED CLAY

Red Hook’s original name was Ihepetonga, the Lenape word for a high point of sandy soil. The modern-day name comes courtesy of the Dutch, who settled there in 1636, when the area was a collection of small islands interspersed with marshes and wetlands, the kind of terrain that must have made them feel right at home.

They named the area Roode Hoek after the area’s red clay soil which would seem to contradict the inspiration (or at least translation) for the Lenape’s name. Technically, coastal Brooklyn’s soil falls somewhere between, neither pure clay nor pure sand but rather “coarse-loamy.” Coarse Loamy Hook, however accurate, just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Despite the dozens of literal red hooks hanging throughout the neighborhood, “hoek” actually means “point” or “corner” in Dutch.

FORT DEFIANCE

At the height of the Revolutionary War, Red Hook’s location at the mouth of New York Harbor was of significant strategic value. In 1776, American forces constructed Fort Defiance on the elevated tip of Red Hook, then known as Cypress Tree Island.

Positioned across the narrow Buttermilk Channel from the larger fortifications on Governors Island, the twin forts were designed to prevent British ships from entering the inner harbor.

The first test came on July 12th, when two British warships set off from Staten Island to probe the defenses. The forts failed spectacularly. Both vessels sailed through the channel and 15 miles upriver to the Tappan Zee without sustaining a single casualty.

The fort fared better a month later during the Battle of Brooklyn, when Admiral Howe sent the HMS Roebuck to intercept George Washington’s retreating troops. Aided by strong headwinds, the fort’s cannon fire forced the ship to retreat to Staten Island, allowing the Continental Army to escape what could have been total annihilation. Of course, they ended up in New Jersey, a fate some New Yorkers might consider worse than death. (Not me; I love New Jersey.)

Constructed mostly of earth and hastily assembled timbers, Fort Defiance left few physical traces. Today, a plaque in Louis Valentino Jr. Park commemorates its location.

ERIE AND ATLANTIC

Though a few intrepid Dutch continued cutting canals and building windmills, Red Hook remained largely a “swampy meadow.” It was the kind of place where one had to "keep a sharp look out for the lurking assassins who infested the neighborhood at the time, and whose knife was ever ready to seek its sheath in the heart of the homeward bound traveler, whose purse offered even a slight remuneration for the trouble."1

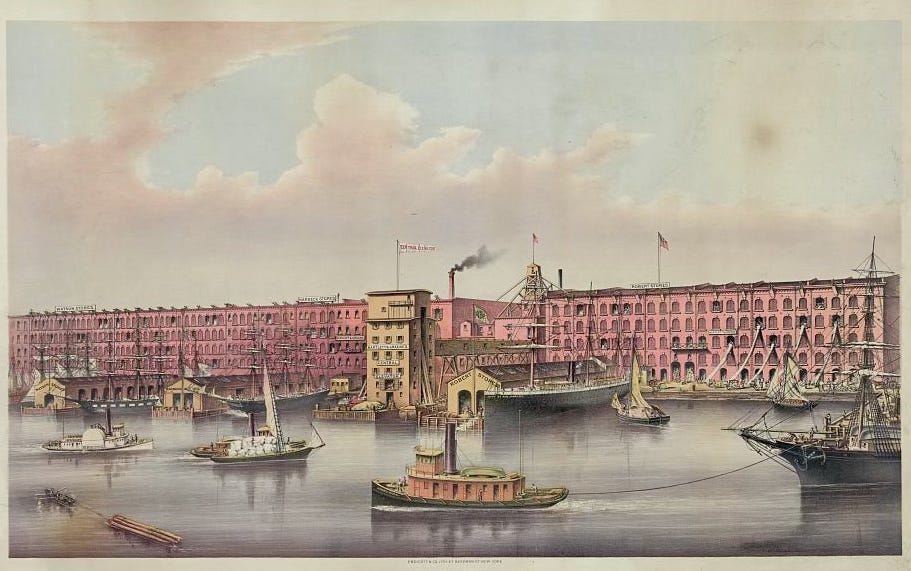

It was the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, connecting Lake Erie with the Hudson River, that transformed Red Hook into a critical juncture in the nation’s grain trade. The Atlantic Docks, constructed in 1840, were built to store imports and accommodate the booming shipping industry.

Soon an unbroken chain of warehouses, grain elevators, piers, and wharves stretched along Brooklyn's waterfront from Williamsburg all the way to Red Hook. From the water, the uniform rows of five-story red brick storehouses, with their distinctive arched windows and iron star washers, created an unbroken front that earned Brooklyn the nickname "The Walled City."

At its peak, Erie Basin became "the busiest place in the Port of New York, where, “the air resounds with the creaking of pulleys, the shouting of the stevedores, and the 'yo--heave--ho' of the sailors.”

HOLY DICK

As Red Hook industrialized, it attracted waves of Irish, German, Scandinavian, and Italian immigrants, who found work as stevedores, longshoremen, coopers, and shipwrights.

In 1846, a group of Irish workers, many of whom had settled in Red Hook after working on the Erie Canal, went on strike at the Atlantic Dock, demanding a raise from their 70-cents-a-day wage. In response, management brought in hundreds of German immigrants willing to work for 50 cents. The strike turned violent, with Irish laborers attacking their replacements and setting fire to worker housing. The Germans held their ground and moved into company-owned shanties along Van Brunt Street.

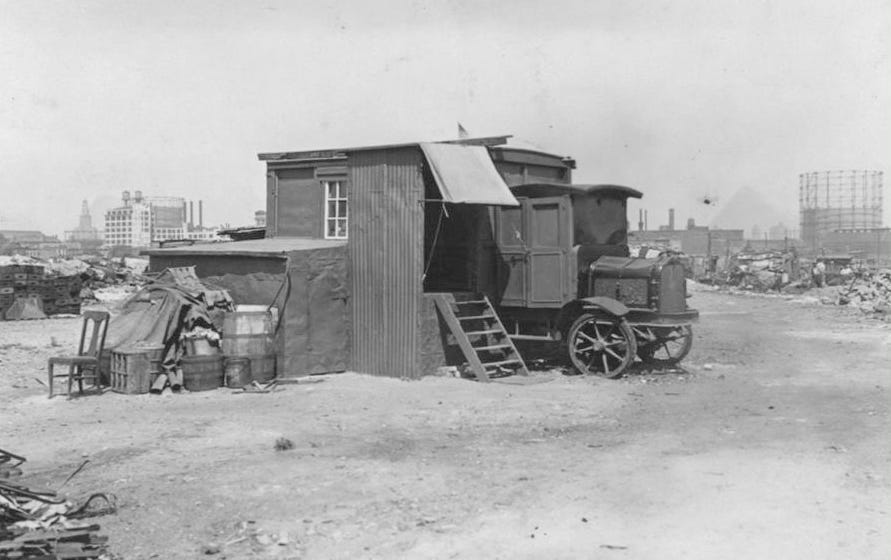

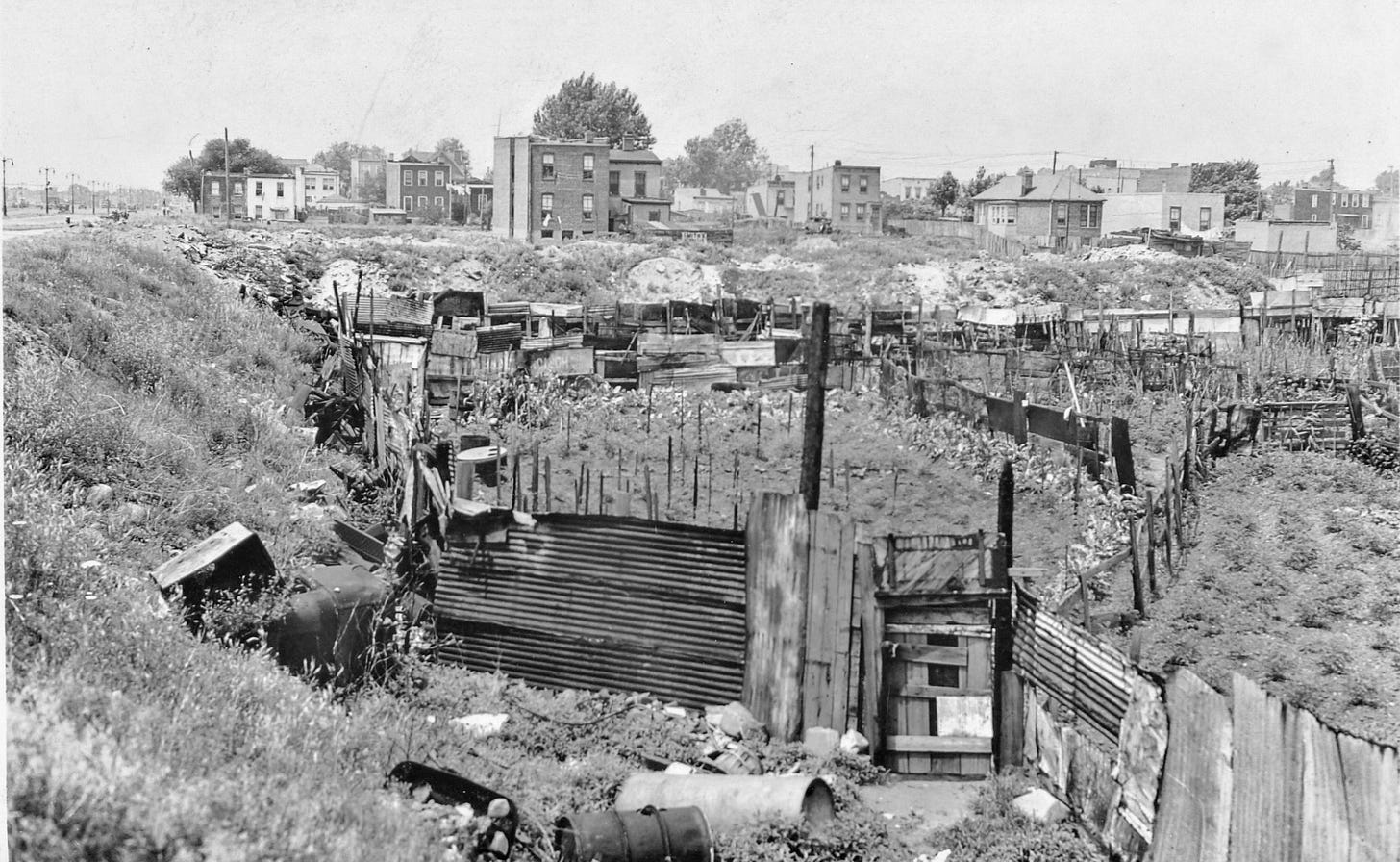

Those shanties were likely an upgrade from the broader patchwork of shantytowns scattered across the peninsula. These were informal settlements cobbled together from salvaged materials reflecting the precarious reality for Red Hook’s early laborers.

Several shantytowns earned nicknames reflecting their distinctive character. Tinkerville, located around Columbia, Richards, and Van Brunt Streets near where the Tesla dealership stands today, was home to Irish tinsmiths more famous for bootlegging whiskey than fixing metal. By day, they wandered the streets calling "any pots or kettles to mend." By night, they met in “solemn conclave” to swap distilling tips and sample their homemade poteen.

The unofficial mayor of Tinkerville was a wiry man known as "Holy Dick," who earned his memorable sobriquet thanks to his deliberately shoddy workmanship. When Holy Dick mended one hole in a customer's pot or kettle, he invariably created two more, guaranteeing return business within the week.

Nearby in the settlement of Slickville, residents endured what was described as a "perpetual state of swampy desperation" by building their homes on stilts or mounted on wheels so they could be hastily rolled to higher ground when rising tides threatened complete submersion.

Other settlements included Slab City, Sandy Bank, and Texas—improvised neighborhoods that the Brooklyn Eagle uncharitably dismissed as "the grand central and amalgamated cesspool and sink of low life in Brooklyn.”

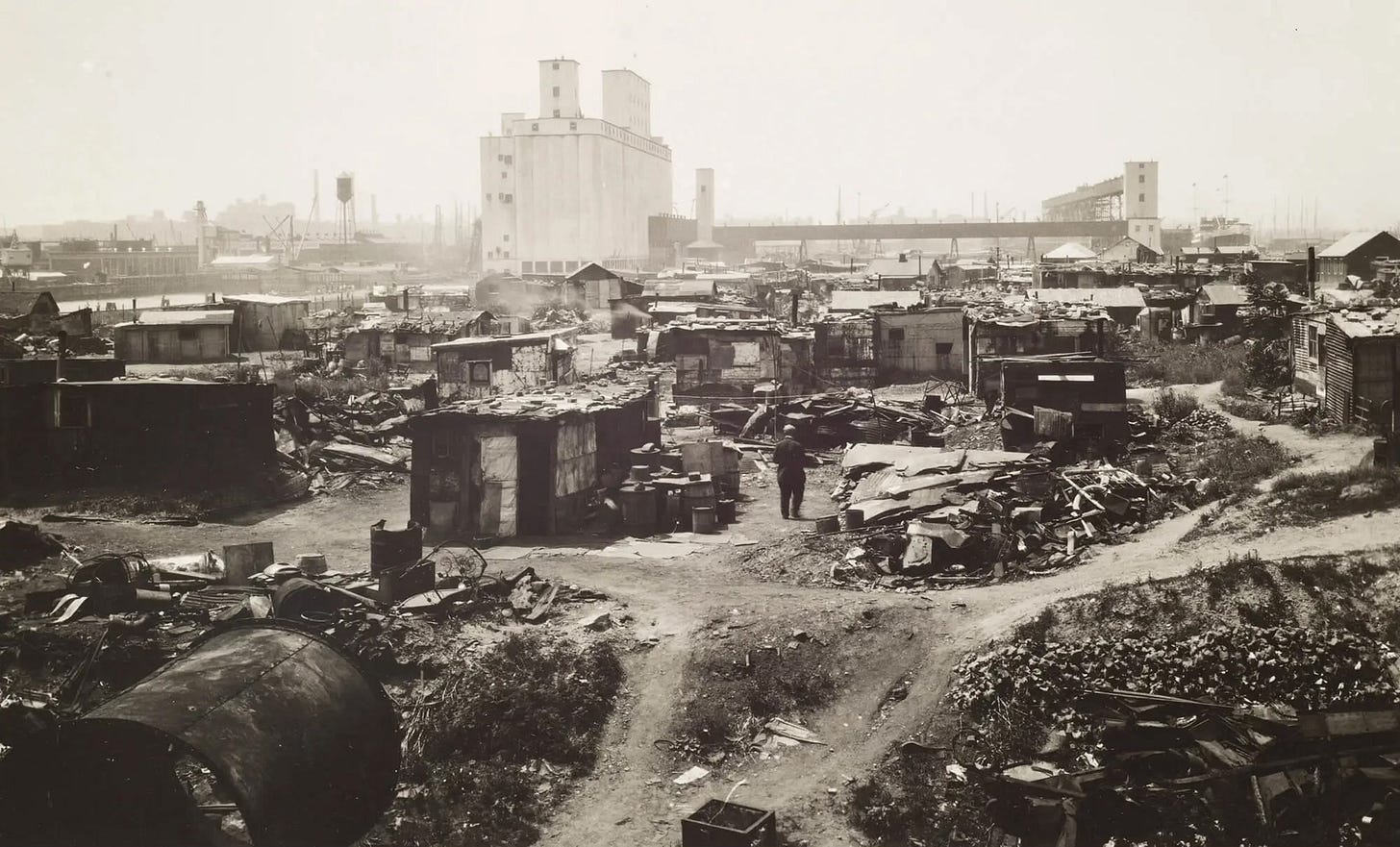

The last and largest of Red Hook's shantytowns began as Ørkenen Sur (the Bitter Desert), established on a garbage dump at Erie Basin's edge by Norwegian sailors stranded when shipping companies couldn't afford return passage. These former seamen built makeshift shelters in the landfill's shadow, salvaging scrap lumber, discarded roofing materials, and old pipes to construct their homes.

The Great Depression's onset dramatically increased and diversified the settlement's population, which at its peak housed over 1,000 residents.

RED HOOK HOUSES

In the 1930s, a fleet of bulldozers cleared the shacks, lean-tos and houses of the Bitter Desert. The land was initially slated for a large housing project, but Parks Commissioner Robert Moses got first dibs on the land and built the Red Hook Recreation Center and Park instead.

The housing development eventually did get built a few blocks away in 1939. The Red Hook Houses was one of the first federally-funded public housing complexes and is still Brooklyn’s largest housing project, home to over 6,000 residents.

Among the original residents were the Caputo family captured by Life Magazine and FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein. The photo below is captioned, “Mr. Caputo watching his wife cook dinner.”

Besides the Caputos, famous former residents of the houses include author James McBride (whose memoir The Color of Water talks about his time growing up in Red Hook), New York Knicks great, Carmelo Anthony, and photographer Jamel Shabazz.

DECLINE

While Robert Moses’ efforts did bring Red Hook a beautiful new park, complete with tennis courts, a running track, and two swimming pools, his most lasting (and damaging) legacy was the Gowanus Expressway. Completed in 1941, the elevated highway severed Red Hook from the rest of Brooklyn. The construction of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel soon followed, reinforcing the neighborhood’s isolation.

These massive infrastructure projects walled off Red Hook at the precise moment when the maritime industry that had sustained it for generations began to collapse. The global shift toward containerized shipping required vast tracts of land and modern equipment, needs that Red Hook’s aging piers and warehouses couldn’t meet. Most shipping operations moved to New Jersey, taking with them thousands of jobs and gutting the local economy.

By 1988, Life magazine named Red Hook one of the ten worst neighborhoods in the country, dubbing it “the crack capital of America.”

In 1992, the community hit its lowest point when Patrick Daly, a beloved principal from P.S. 15, was killed in the crossfire between rival gangs. The killing shocked the city and drew attention to the conditions inside New York’s public housing complexes. But it also galvanized the community. Residents, educators, and local leaders began organizing, efforts that would eventually lead to the creation of outreach programs like the Red Hook Initiative (established in 2002), dedicated to youth empowerment and social justice.

On the other side of the neighborhood, artists, the canaries in the gentrification coal mine, were starting to move into some of the dilapidated houses around Van Brunt Street. Then came Fairway, which retrofitted a pre–Civil War coffee and cotton warehouse into a waterfront grocery store with easily the best view in the city. IKEA followed in 2008, opening on the bones of the old Todd Shipyard graving dock, bringing the neighborhood flat-pack furniture and, more importantly, jobs.

Restaurants like 360, Hope and Anchor, and the Good Fork opened around the same time and soon, Red Hook was a destination.

Then came Hurricane Sandy. In 2012, the superstorm submerged much of the neighborhood, flooding homes and businesses and plunging the Red Hook Houses into darkness for weeks.

While the entire neighborhood is in a flood zone, development continues. Recently, the Port Authority transferred ownership of the 122-acre Brooklyn Marine Terminal to the NYC Economic Development Corporation, which aims to transform the site into the "Harbor of the Future"—with a modernized port, hotel, and 7,700 new apartments.

A vote on the controversial proposal is scheduled for next week.

RED HONEY

My favorite Red Hook story (before I learned about Holy Dick) starts with the 2010 discovery by beekeepers in Red Hook that their bees were producing honey with a sickeningly red hue. While it sounds like an elaborate stunt cooked up by the Red Hook chamber of commerce, further testing revealed the presence of Red No. 40, a synthetic food dye used in everything from Fruity Pebbles to mouthwash.

It turns out the local bees were gorging themselves on the spillage outside of Dell’s Maraschino Cherries, a family-run factory at the corner of Dikeman and Ferris Streets. Founded in 1948 by Italian immigrants from Naples, the Mondella family business produces over fourteen million pounds of bright red cherries each year.

Arthur Mondella Jr. had no intention of joining the family cherry business. After earning a business degree, he was working at an investment firm on Wall Street when his father suffered a heart attack. Arthur Jr. decided to step in and run the company, commuting daily from Graniteville, Staten Island, and eventually doubling the factory’s capacity. Under his leadership, Dell’s cherries found their way into Manhattans, Shirley Temples, and ice cream sundaes served at chains like Buffalo Wild Wings, TGI Fridays, and Red Lobster.

Five years after the red honey was traced to Dell’s, though, the story took a dark turn.

On February 24, 2015, two dozen officers from the Department of Environmental Protection, NYPD, and the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office descended on Dell’s with a warrant to search for evidence of illegal dumping. As they moved through the facility, they caught a strong whiff of marijuana and noticed what appeared to be a false wall. When they informed Arthur that they were securing a second warrant to search behind it, he asked to be excused to the bathroom.

There he retrieved a .357 Magnum from his ankle holster and shot himself in the head.

Behind the wall, officers discovered a subterranean 2,500-square-foot marijuana grow operation, 100 pounds of recently harvested cannabis, $130,000 in cash, and a well worn copy of The World Encyclopedia of Organized Crime.

Arthur’s family had been kept completely in the dark about the operation and investigators never found out who else was involved. The Mondellas paid a $1.2 million fine and still run the factory today.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio is mostly just the sounds of a dog insisting his toy get thrown back into the waters off of the beach Louis Valentine Jr. Park.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I featured Jade Doskow’s work as photographer-in-residence of Freshkills Park in my coverage of Staten Island’s Travis. You can see some of that work at the Staten Island Museum in the show Breakdown: The Promise of Decay, up through September. Today, I’m sharing photos Jade made in Red Hook where she has lived, on and off, since 2003.

Jade is teaching a five day workshop on photographing the Brooklyn waterfront (from Red Hook to Coney Island) from June 23-27 through the International Center of Photography (ICP).

ODDS AND END

I unfortunately don’t spend as much time in Red Hook as did when I lived closer but Jade was nice enough to share some neighborhood hotspots. Black Flamingo for coffee, 360 for records, Baked for sweets, and the café inside the Food Bazaar (which replaced Fairway) for lunch with a view.

Of course no trip to Red Hook is complete without a trip to Sunny’s, preferably on Wednesday when the great Smokey Hormel holds court.

An incredible resource for all things Red Hook is the Red Hook Water Stories website.

I didn't even get into Red Hook's extensive mafia history, which includes the backstory behind how Al Capone earned his nickname, Scarface. If you want to learn more about that side of the neighborhood's history, pick up a copy of Frank DiMatteo's Red Hook Brooklyn Mafia: Ground Zero. Or just fuggetaboutit.

The Norwegian Documentary on the Bitter Desert: "Ørkenen Sur"

It’s really interesting to read the New York Magazine piece “The De-gentrification of Red Hook” eighteen years after its publication, especially in light of Hurricane Sandy and the recently announced plans for the Brooklyn Marine Terminal.

In that sense, Red Hook is lucky to be Dead Hook: on the firebreak of super-gentrification, the neighborhood was spared, rather than consumed. And in the future, when we look back at these gold-rush years, we might remember Red Hook not as the Wild West outpost that was the last hot neighborhood to gentrify, but as more like the Alamo—the first hot neighborhood that didn’t.

Red Hook Point: 30 Years in the Slums", The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 2, 1872 · Page 4 https://www.newspapers.com/article/brooklyn-eagle/174487199/

The photos in this issue are some of your best ever. That shot with the Statue of Liberty way in the back. SO GOOD. The umbrella lady? Magical! Every photo deserved framing, hanging, and admiring.

But unfortunately they're eclipsed by the Red 40 bees. That whole story is an unbelievable (I won't make the bee pun) ride through some truly fascinating history. Holy crap. If you'd have told me to connect the dots between red honey and busting an organized pot ring, I'd never have alit on even ONE of these points. I'm so filled with a weird joy that things like this happen. I mean, the suicide was bleak, but the story is incredible. I'm abuzz, honey.

Total missed opportunity to not use the can of Manwich to hold up an a/c unit 🤷

But also I'd love to give another shoutout to the Red Hook Initiative! I've volunteered with them before picking vegetables at their garden across the street from Ikea and they were really lovely to work with. They also do amazing work in the neighborhood that really helps out the lower income residents. The folks working there are very knowledgable about the neighborhood, too!