🌟 Quick Note! My work from the Neighborhoods project will be exhibited for the first time at the Future Fair in Chelsea this week. You can see it at the 3walls booth through May 10th. The fair is located at 535 W 28th St, and hours are 12-7 PM on Thursday and Friday and 12-6 PM on Saturday. I hope you can make it!

One of my favorite times to photograph is early Sunday morning, when most of the city is still asleep, the streets are empty, and the light is soft. If I happen to be driving, I always have WKCR on, whose Sunday morning broadcast starts with two hours of field recordings followed by two hours of gospel, which is pretty much the perfect way to start a day.

Last weekend, when I looked at the upcoming week’s weather report, I realized Sunday was out. So were Monday, Tuesday, and probably Wednesday. Four straight days of rain. If I wanted to get any pictures for this week's newsletter, I had to get off the couch and head out that very (sunny) afternoon. The only thing worse than shooting in the rain is shooting under a hot, bright blue sky—but sometimes you have to play the hand you're dealt.

When I emerged from the G train onto the steamy sidewalks of Greenpoint, the neighborhood was buzzing. I passed a rosé tasting, a DJ spinning vinyl, a Pilates sock pop-up, and a bespoke pizza stand. And that was all in the same place. Lucky Honey, New York City’s “premier grip sock and activewear brand,” was throwing a party to celebrate World Wide Pilates Day.

It's the kind of business and event that feels emblematic of the new Greenpoint, one of the fastest-gentrifying neighborhoods in the city. The transformation, kick-started by the 2005 waterfront rezoning, has dramatically changed a neighborhood sometimes known as "Little Poland," which at one point was nearly 80% Polish. Today, however, Greenpoint is better known for pour-overs and pop-ups than for pierogi and piwa.

The neighborhood even has its own signature scent—and I don’t mean the heady aroma emanating from the iconic digester eggs that dominate the Greenpoint skyline, quietly processing 1.5 million gallons of New York City’s sewage every day.

No, I’m talking about Greenpoint by Bond 9, a $470 fragrance with a bergamot top note designed to capture the “edgy maritime neighborhood with a slightly industrial, bohemian vibe.”

The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Greenpoint is an astonishing $5,350—not bad for a neighborhood boasting not one but two active Superfund sites. Those numbers are skewed by the glut of new apartment buildings that have sprouted up along the East River in recent years. Projects like the 22-acre, $1 billion Greenpoint Landing, which, when completed, will consist of 11 residential towers providing a total of 5,500 housing units, and the Eagle + West towers, which look like Rem Koolhaas designed them between games of Tetris.

Greenpoint has a diverse range of architectural styles, everything from rows of meticulously maintained townhomes to wooden-frame houses with intricate shinglework to… whatever this is:

The neighborhood’s borders are defined by the East River to the west, Newtown Creek to the north, the BQE to the east, and (roughly) Bushwick Inlet Park and McCarren Park to the south.

Several people have pointed out Greenpoint’s uncanny resemblance to the profile of one of the stars of Mike Judge’s Beavis and Butt-Head.

THE NORMAN

A traveler in those times gazing at Green Point from a boat on the East River would have noticed many high sandy headlands, remnants of the early glacial period, similar to those still remaining along the north shore of Long Island. Near where the foot of Freeman street now lies, a point of land jutted abruptly beyond the shore line into the river for a considerable distance. This point, covered with river ooze and green grass, naturally attracted the gaze of the sailors on passing vessels, who gave to this verdant projection the name of Green Point.1

The first European to settle in Greenpoint was a Norwegian carpenter named Dirck Volckertsen, sometimes known as “The Norman.” In 1638, the Dutch West India Company negotiated with the Keskachauge Indians to allow settlement in Brooklyn, and a few years later, Dirck received a grant to buy 400–500 acres between Norman Kill (Bushwick Creek) and Newtown Creek.

Dirck was said to have “thrived on litigation,” and his name appeared frequently in court records - sometimes as plaintiff, sometimes as defendant. He was involved in disputes over a boar (his), a canoe (not his), and even his claim to the land itself. In that case, brought by a barrel maker named Jan De Pree, Volckertsen prevailed. Years later, the two would face off in court again—this time after Volckertsen stabbed De Pree in the stomach during a game of dice. That case, he lost.

Volckertsen built a stone farmhouse near what is now Calyer Street, west of Franklin Street. Like in nearby Astoria, the fledgling settlement spent its early years under siege from the Keskachauge who, understandably, were not thrilled with the terms of the real estate deal.

Eventually, with the founding of nearby Boswijck (Volckertsen was among the signers of its charter), European settlements in the area began to take root.

BLISS

While The Norman may have been the first European to settle in Greenpoint, Neziah Bliss is considered its founding father. You may remember Neziah as the man who founded the ironically named Blissville—the diminutive Queens neighborhood just across Newtown Creek, one of the most polluted waterways in the country.

In the 1830s, Bliss purchased thirty acres along the river and married Mary Meserole, daughter of one of the five Huguenot families who had been Greenpoint’s only residents for the past century. He moved quickly, surveying and mapping new streets and building a bridge and turnpike connecting the area with Williamsburg and Astoria. He also established a regular ferry service between Greenpoint and Manhattan.

Neziah, not one for creative naming, labeled the east–west streets with single alphabetical letters. In later years, those street names were elaborated upon. A became Ash, B became Box, C became Clay, and so on.

The construction of bulkheads and wharves to accommodate the fleets of merchant vessels provisioning the rapidly growing city was transforming Manhattan’s waterfront. The shipyards that once lined the banks of the East River needed to find a new home. Once ferry service was in place, Greenpoint’s shoreline, where the water reached an impressive 25 feet deep even at low tide, became a coveted location for shipbuilding. Within a few years, the fertile fields and orchards once belonging to the Provosts and Caylers were dug up, their loamy soil crammed into the massive bulkheads erected along the river’s edge.

The salt marshes were converted into solid ground, and by the mid-19th century, Greenpoint had become one of the busiest shipbuilding centers in the world.

Mammoth piles of lumber lay about waiting for use—white oak, hackmatack and locust for ribs, yellow pine for keelsons and ceiling timbers, white pine for floors, and live oak for aprons. Through the air was wafted the odor of damp pine chips, of pitch and of oakum, while the ceaseless clatter of mallets and busy saws gave evidence of strenuous industry. The workers came in large numbers, attracted by the permanent character of the work, bringing their families and taking up their residence here.2

MONITOR

While Greenpoint’s shipyards were celebrated for their clipper ships—the narrow, multi-masted schooners prized for their beauty, speed, and nimble handling—the most famous vessel to come out of North Brooklyn was almost their antithesis.

The USS Monitor, built by the Continental Iron Works in 1862, was described by one observer as “a cheese on a raft.” It was an early ironclad: a low-slung, steam-powered vessel sheathed in steel, designed to present as little targetable surface area as possible. Nathaniel Hawthorne, witnessing the strange new craft, called it a “gigantic rat-trap… It was ugly, questionable, suspicious… devilish; for this was the new war-fiend, destined… to annihilate whole navies and batter down old supremacies.”

Hawthorne’s observations were made after the Battle of Hampton Roads, the Civil War clash that pitted the USS Monitor against the CSS Virginia, the Confederacy’s own ironclad. The battle—the first of its kind between two armored warships—ended in a tactical draw. Neither ship could pierce the other’s armor. But the smoldering remains of the wooden-hulled ships caught in the crossfire marked a sea change in naval warfare technology.

The Monitor’s impact was so profound that an entire class of similar vessels would be known simply as “monitors.” The man who designed it, John Ericsson, is honored with a particularly flattering statue in McGolrick Park.

From the looks of it, when he wasn’t designing impregnable watercraft, Ericsson was putting in some serious time on the pilates reformer.

ASTRAL OIL

After the war, shipbuilding moved west and north, lured by cheaper labor and easier access to raw materials. But by then, Greenpoint had already been transformed. Industries that sprang up during the shipbuilding boom—lumberyards, ropewalks, printshops, and oil refineries—were thriving. Dozens of workshops and factories buzzed with the nonstop production of durable goods like porcelain, pencils, glass, and cast-iron boilers, drawing waves of immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Russia, and especially Poland. Newtown Creek became one of the busiest waterways in the country; in 1915 alone, more than 100,000 ships passed through, carrying over five billion tons of cargo.

Charles Pratt (of Clinton Hill fame) opened his Astral Oil refinery on the banks of Newtown Creek in 1867.

To house his workers, he built the Astral Apartments, which still span the entire block of Franklin Street between India and Java Streets. It was a rare development for the era—one that prioritized the health and well-being of its tenants. Every unit had at least one window, hot and cold running water, a stove, and a separate toilet room. Scouting New York has a great write up on the apartments.

Pratt’s success—he later merged with John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil—funded the creation of Pratt Institute and a series of mansions along Clinton Hill’s “Gold Coast.” It also inspired others to get into the business, and by 1870, more than 50 refineries lined the banks of Newtown Creek.

SUPERFUND

An over one hundred year history of refining oil was not without its drawbacks. Dating back to the earliest days of Astral Oil, newspapers were filled with accounts of numerous incidents detailing terrific explosions and flaming rivers.

In 1950, an explosion in the sewer system, centered at Huron Street and Manhattan Avenue, likely caused by a large quantity of kerosene leaching into the system, blew twenty-five manhole covers three stories high, sending locals running for cover from what they feared was an atomic bomb.

Then, in 1978, a Coast Guard helicopter flying a routine training mission noticed a slick of black oil flowing into Newtown Creek from a bulkhead at Meeker Avenue. Further testing of the water and soil revealed an oil spill estimated to be three times larger than the Exxon Valdez disaster—an underground pool containing approximately 30 million gallons of petroleum. It was determined that the spill was not an isolated incident but rather “the toxic culmination of 140 years of spillage.”3

Mobil (who had taken over most of Standard Oil’s refineries) set up some pumps to remediate the site, but this was a disproportionately small response to a catastrophic situation. Then, in 1990, Mobil spilled an additional 50,000 gallons of oil into Newtown Creek.

Eventually, after public and legal pressure from the DEC and organizations like Riverkeeper, Mobil increased its cleanup efforts. An estimated 12.9 million gallons of oil have been pulled out of the creek.

In 2007, while monitoring one of the oil plumes running under the neighborhood, the DEC found a significant accumulation of highly toxic chlorinated volatile organic compounds (CVOCs). What has been dubbed the Meeker Avenue Plume had spread underneath nearly 45 blocks of residential, commercial, and industrial properties on the Greenpoint/East Williamsburg border. The potential toxicity of the CVOCs, which came from illegally dumped waste from dry cleaning businesses and metalworking shops, is so severe that the Meeker Plume joined Newtown Creek on the Superfund list in 2022.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio starts out with some classic Brooklynese before heading off to McCarren Park running track and the sounds of people in way better shape than seizing the day while I eat a Peter Pan donut. Then there is some audio from Bushwick Inlet Park, and a brief foray into Radio, Greenpoint’s buzziest purveyor of baked goods.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

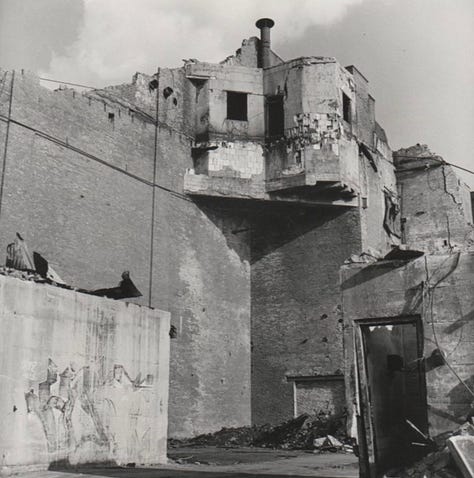

Beginning in 1988, photographer Anders Goldfarb (b. 1954, Brooklyn) set out to document his new neighborhood of Williamsburg and neighboring Greenpoint, exploring the yet to be gentrified streets on his three-speed Raleigh. Shooting with a Rolleiflex TLR, Goldfarb turned his lens toward often-overlooked and neglected subjects: crumbling buildings, peeling siding, overgrown lots, and abandoned spaces. His black and white photographs imbue these scenes with a quiet pathos, capturing the stark beauty of places on the brink of disappearance.

In 2021, DCV Books in Berlin published Passed Remains: Greenpoint/Williamsburg 1987–2007, a collection of Goldfarb’s work documenting the North Brooklyn waterfront. His most recent book, Ash Avenue, was published by Red Hook Editions last year.

Anders doesn’t have a website, but his Instagram is @andersgoldfarb.

Here is a great video that follows him around the neighborhood while he discusses his work.

ODDS AND END

While I barely scratched the surface of Greenpoint, there are a ton of places to read up on in the neighborhood, all of which helped me in my research this week. There is the website Greenpointers, Geoffrey Owen Cobb’s books and blog on Greenpoint history, and the excellent Greenpoint Tales, which collects and shares stories from local residents.

Besides stories, Greenpoint Tales features the work of photojournalist Robert Nickelsberg, who worked as a Time magazine photographer for nearly thirty years, specializing in political and cultural change in developing countries. He has documented the rise of religious extremism in South Asia, open-pit gold mines and miners of Brazil, and domestic sex trafficking. His most recent project has him working with an 8x10 camera, capturing portraits of Greenpoint’s Polish Community.

Must-see mid-80s Greenpoint related movies that probably appeal to two very different audiences: Christine Noschese’s 1985 documentary, Metropolitan Ave, and the body horror classic, Street Trash.

Several years ago, I was working on a commission for the Center for Architecture documenting adaptive reuse, specifically non-landmarked buildings that “could easily have been demolished, but instead were preserved and transformed for new use.” One of those buildings housed the Sunview Luncheonette, a former greasy spoon that reopened after closing in 2008 as a “microvenue for art, poetics, regionalism, mutual aid, and commoning.” Sunview became a unique cooperative of local artists, academics, urban planners, and poets who presented shows, hosted talks, served dinners, and created a community gathering spot. They even had their own risograph machine in the back. Just this past year, the building housing the Luncheonette, 211 Nassau Avenue, was sold. According to their website, Sunview will be moving to a new location.

I will send three postcards to the first person in the comments who can name these three reclining Greenpoint icons without looking them up. If you make it to the Future Fair, you can grab a stack of postcards there too—no guessing required.

From Historic Green Point or “a brief account of the beginning and development of the northerly section of the borough of Brooklyn, City of New York, locally known as Green Point,” William Felter, 1918

IBID

http://www.newtowncreekalliance.org/greenpoint-oil-spill/#endnotes

Love this one Rob. I only recognize Pat Benatar in the icons :)

Amazing photography and background, as always. Really appreciate this newsletter!

I'll always connect Greenpoint to the short-lived underground dub/hip-hop movement called Illbient back in the late 1990s. Over here, we imagined the area as this kind of industrial wasteland with artists and musicians flocking in from the city (as Manhattan became way too expensive), making music under the influence of the ultra-strong Jamaican weed that was sold at the corners... that's probably just nostalgic romanticism, but it's how it was portrayed for example in this semi-legendary indie film which documented that Greenpoint scene – it's called "Crooked", was produced by Skiz Fernando Jr. and came out via the WordSound imprint that also released the "Crooklyn Dub Consortium" compilations.