I live on Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn, the dividing line between Fort Greene and Clinton Hill. There is surprisingly little controversy about this demarcation. The west side of the street, my side, is considered Fort Greene, while the other side is Clinton Hill. In the 19th century, both neighborhoods were collectively known as "The Hill." While the whole area has gone through a familiar trajectory —farmland, rural retreat, brownstone boom, industrial expansion, disinvestment, gentrification—Clinton Hill's grand architecture, a vestige from its time as the "Gold Coast” of Brooklyn, differentiates it from its neighbor to the west.

Besides Vanderbilt Ave, Clinton Hill's other borders are Classon Avenue to the east, Atlantic Avenue to the south, and Myrtle Avenue to the north. Some maps have the neighborhood extending to Flushing Ave, but that would sadly ignore the neighborhood of Wallabout, which I'm not about to do, especially since I have already devoted a whole newsletter to it.

THE HILL

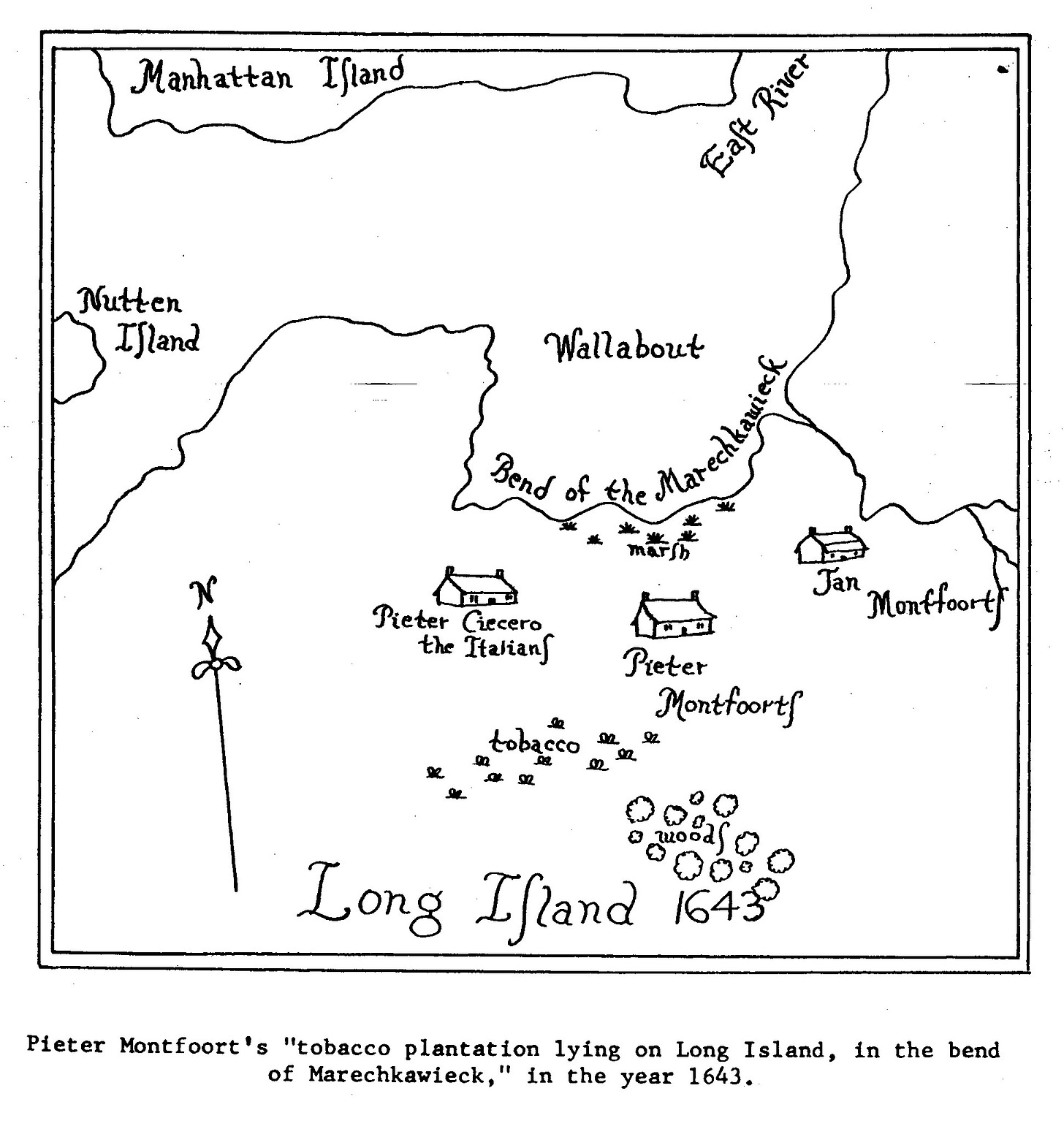

Walloon and Dutch farmers established some of the first European settlements in Brooklyn along the shoreline of Wallabout Bay, just north of present-day Clinton Hill.

Dutch farmer Pieter Montfoort had a tobacco farm in the Clinton Hill area that he later sold to another farmer, John Spader.

Spader then sold the farm to merchant and auctioneer George Washington Pine, who began subdividing the land. The broad, tree-lined Clinton Ave, named after New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, was the neighborhood’s showpiece, designed to attract wealthy residents who wanted a large home in the country. The area’s elevation made it a draw, as the swamps of the lowlands were associated with disease.

Clinton Avenue was soon lined with freestanding villas surrounded by large lawns and carriage houses in the back, which opened up on the surrounding streets of Waverly and Vanderbilt.

In the 1860s, after several streetcar lines had been built and ferry service had reduced the commute to Manhattan down to a mere 12 minutes, speculators started filling the surrounding blocks with rows and rows of French Second Empire, Italianate, and Neo-Grec townhouses. Bankers, lawyers, and businessmen lined up to purchase the homes.

GOLD COAST

In 1874, Standard Oil executive and all-around moneybags Charles Pratt decided to settle down on the Hill and built a large mansion at 252 Clinton Avenue. Other millionaires soon followed suit. Many of the freestanding villas built in the 1830s and 40s were demolished, making way for the even grander mansions that would give Clinton Avenue its new nickname, the "Gold Coast."

Montrose Morris and William Tubby, the starchitects of their day, built homes for industry leaders like coffee merchant John Arbuckle, lace manufacturer A.G. Jennings, and baking powder magnate Dr. C.N. Hoagland.

Incidentally, this is the third different baking powder magnate I have written about in this project. Robert Benson Davis, who had an enormous mansion in Bloomingdale on the Upper West Side, and William Ziegler, who came up in the Malba edition of the newsletter, both made boatloads of money selling what seems like the most prosaic of ingredients. In contrast to today's billionaires whose riches are made from high frequency trading and algorithm driven advertising, the well-heeled denizens of Brooklyn's Gold Coast made their fortunes in the manufacturing and selling of durable goods—everyday items like baking powder, beer, typewriters, and lace.

The Hill was particularly lousy with Pratts as Pratt Senior had decided that sugar bowls and napkin rings were too obvious to give as wedding gifts and instead built mansions for four of his sons and their new brides.

To cement the Prattification of the neighborhood, the 25 acre campus of Pratt Institute opened in 1887. Pratt, who did not attend college, wanted to provide an education "to people from all walks of life, irrespective of their standing in society."

The school, which mixed the fine arts with the practical, offered classes in bricklaying, cooking, and plastering, as well as painting, drawing, and photography. When the institute opened in 1887, there were 12 students; by 1892, there were 3,900.

THE BROOKLYN ENIGMA

Meanwhile, a few blocks south of Pratt, Mollie Fancher was ending her reign as the Brooklyn Enigma.

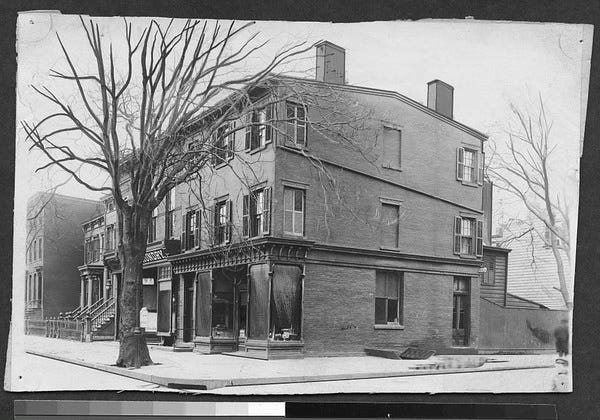

Fancher, born in 1848 in Attleboro, Massachusetts, moved with her family to a house at 160 Gates Avenue in Clinton Hill when she was just two years old. She would stay for the rest of her life.

In 1865, Mollie was riding through Prospect Park when she was thrown from her horse, hitting her head on the pavement and breaking several ribs in the process. She eventually recovered, but just a year later, while exiting a horse-drawn trolley on Fulton Street, her hoop skirt got caught, and she was dragged for a block until the shouting passengers finally got the driver's attention.

The cumulative effect of her accidents manifested themselves a few months later while she was spending the morning helping her aunt in the kitchen of 160 Gates.

“she suddenly shrieked, stood on her toes, and spun around like a top. Then, she bent forward, clasped her feet in both hands, and began rolling about the floor.”

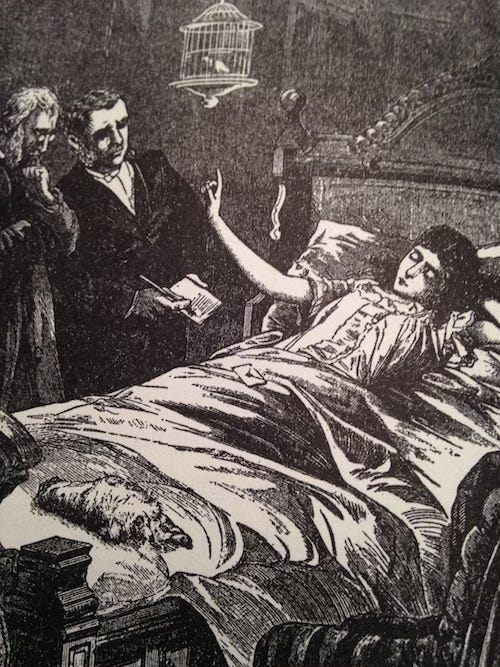

Mollie had difficulty walking and had several episodes where her whole body was wracked with spasms, forcing her limbs to contort and freeze in unnatural positions. She was unable to eat or drink.

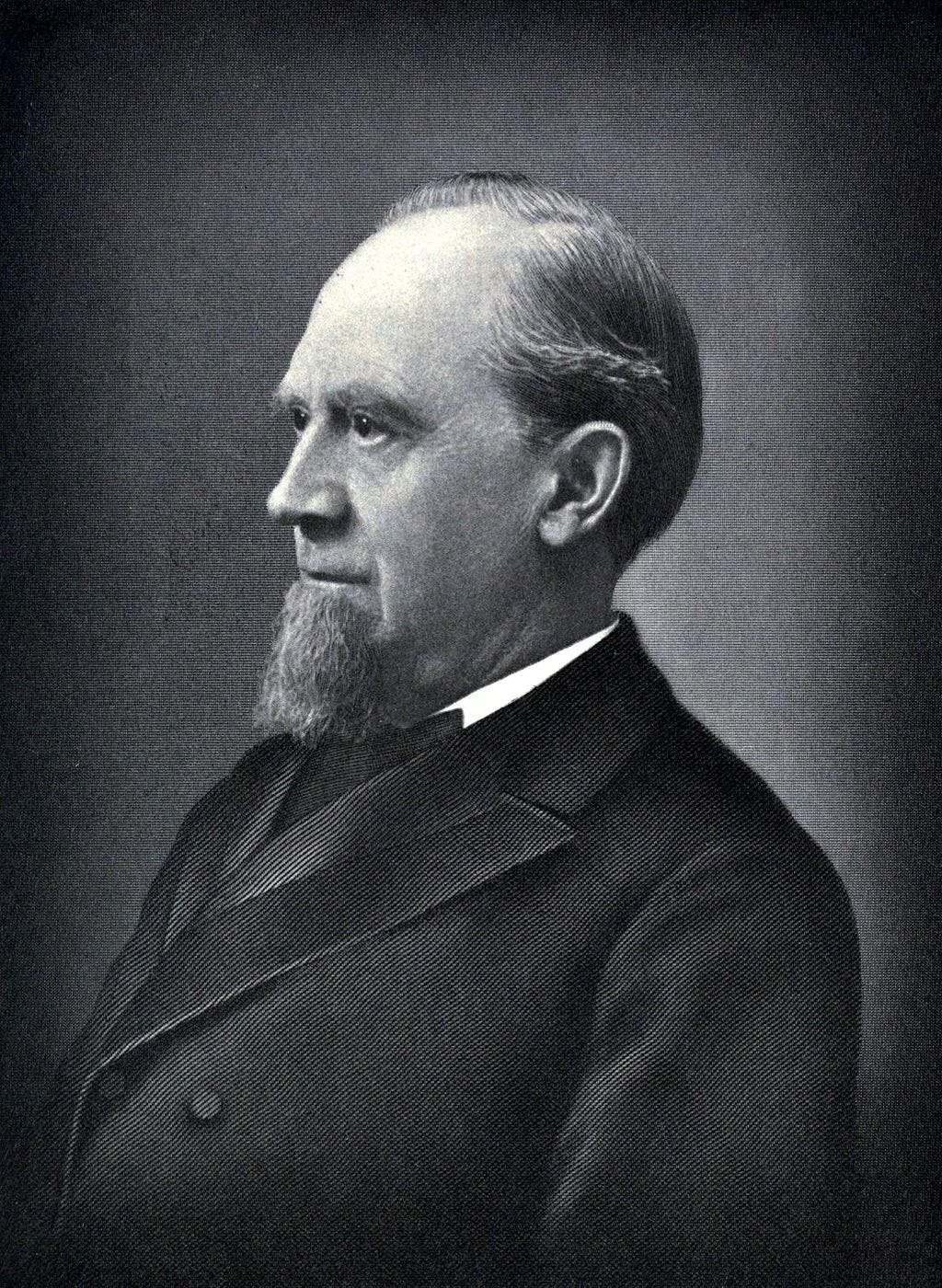

Several prominent doctors employed a variety of unconventional techniques to help Mollie. When repositioning her bed to align with the earth's magnetic currents and placing a large horseshoe magnet at her feet failed to have the intended result, they turned to other, more extreme treatments, several of which would seem to violate the terms of the Geneva Convention.

First up was a steam bath of dry alcohol. Mollie was placed into a bathtub with several alcohol-burning lamps and covered with blankets up to her chin. This turned out to be not such a great idea as the extreme heat trapped by the blankets caused parts of her skin to bubble and peel off.

Then she had to sit in a tub filled with extremely hot water while somebody poured buckets of ice-cold water on her head until she fainted. Another treatment involved being wrapped in ice-cold sheets.

Then there were the beef tea enemas.

The breaking point (which, frankly, for me, would have been the beef tea enemas) involved a custom ice jacket. The jacket had five waterproof bladders, each filled with ice - one on her stomach, three on her spine, and one on her head. As someone who can't attend a social event without sweating profusely, this garment sounds like a godsend, but for Mollie, it was torture. She hurled the bags of ice across the room in a rage.

“I have a temper, and it was then aroused.”

Soon after, perhaps in an attempt to avoid any more treatments, Mollie fell into what was described as a nine-year trance. During this so-called "trance," she wrote more than 6,500 letters, crocheted over 100,000 ounces of wool, and constructed a great number of "decorative waxwork flowers and leaves." She also sewed a quilted lining for her coffin.

She did all this with her right arm essentially frozen behind her head and the fingers of both hands clenched together. At the end of the trance, Mollie woke up, looked around, and probably said something to the effect of, "What's with all the waxwork flowers?"

Though she was practically blind and deaf and remembered nothing from the past nine years, Mollie had emerged from the trance with psychic powers. She could predict future events, accurately describe "the dress and demeanor of a friend" in another town, and read books just by touching them. She was also accompanied by five new personas: Sunbeam, Idol, Rosebud, Pearl, and Ruby.

Here is a handy guide to their personalities:

Sunbeam, befitting of her name, thrived in sunlight and managed the household affairs. She excelled in creative crafts such as embroidery and crocheting and could make waxwork flowers like nobody’s business. Sounds like someone we know…

Idol had a jealous personality and tried to sabotage Sunbeam’s work. She cried a lot and complained of having no friends. I wonder why you don’t have any friends, Idol?

Rosebud sounds like the most annoying of the lot. She supposedly “prattled almost incessantly in baby lingo” and entertained visitors by “imitating the cackling of hens, the mewing of cats, the bleating of sheep, the grunting of pigs.”

Pearl was said to have a spiritual personality and was known for her interest in poetry and the arts. Mollie wrote most of her poems while under Pearl's influence.

Ruby was the Yang to Pearl’s Yin— an energetic and extroverted counterpart with a flair for making dramatic entrances and exits. She was described as hoydenish, which Merriams defines as a girl or woman of saucy, boisterous, or carefree behavior.

Mollie was perhaps most famous for her ability to get by on practically no food. For one seven-month period, she was reported to have consumed only "four teaspoons of milk, two teaspoons of wine, one small banana, and one cracker."

The phenomenon of the "fasting girl" had been around since at least the Middle Ages, with women like Angela of Foligno and St. Catherine of Siena practicing long fasts to demonstrate their devotion. The tradition returned to vogue in the 19th century, an age of rampant spiritualism and pseudo-scientific beliefs. Many of the miraculous fasters were proven to be hoaxes, while others were likely suffering from anorexia nervosa, though the diagnosis had yet to come into widespread usage.

Though all who had observed her powers found them convincing (including PT Barnum, who offered her mattress stuffed with swan's-down and gold-plated bed if she would go on tour with him), there were skeptics. In 1894, the psychology department of the New York Medico-Legal Society proposed a scientific inquiry into Mollie's powers, but by then, her powers had begun to wane, and her health had improved. Her limbs loosened, she regained her appetite, and she began gaining weight. By the mid-1890s, the Brooklyn Enigma was a mystery no more but "merely a bedridden old woman with a passion for embroidery and crocheting." And parrots.

Mollie Fancher died in 1916. She is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

JUST KIDS

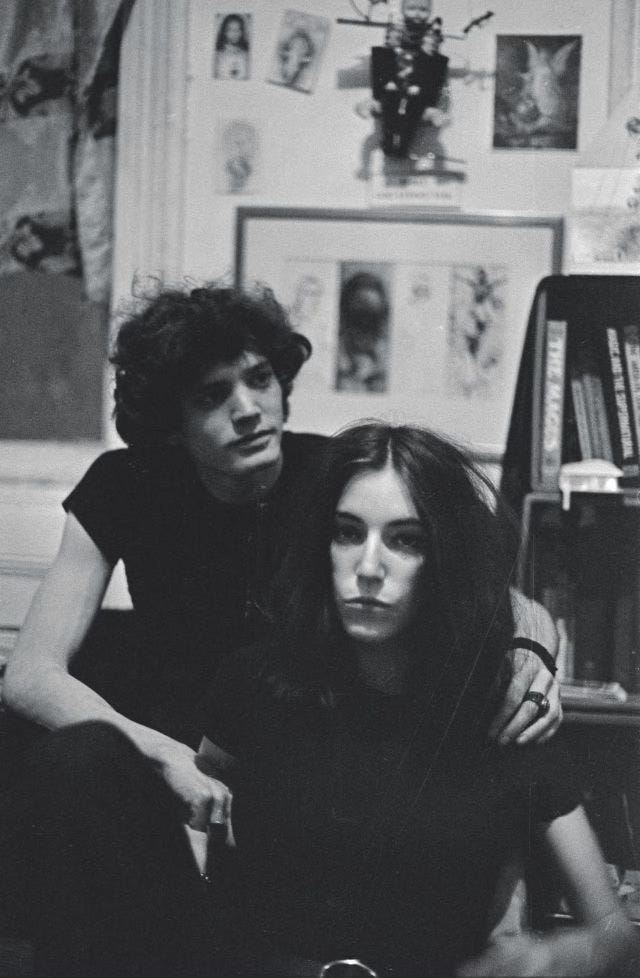

One hundred years after Mollie Fancher put 160 Gates on the map, Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe did the same at 160 Hall. Smith wrote about the second-floor apartment the two shared in her 2010 memoir, Just Kids.

Its aggressively seedy condition was out of my range of experience. The walls were smeared with blood and psychotic scribbling, the oven crammed with discarded syringes, and the refrigerator overrun with mold.”

In 1967, their monthly rent was $80. Today, you would need to add two zeroes to that number. To be fair, that $8,000 gets you the whole building and a brand-new Sub Zero fridge with plenty of room for discarded syringes and a case of small-batch kombucha.

B.I.G.

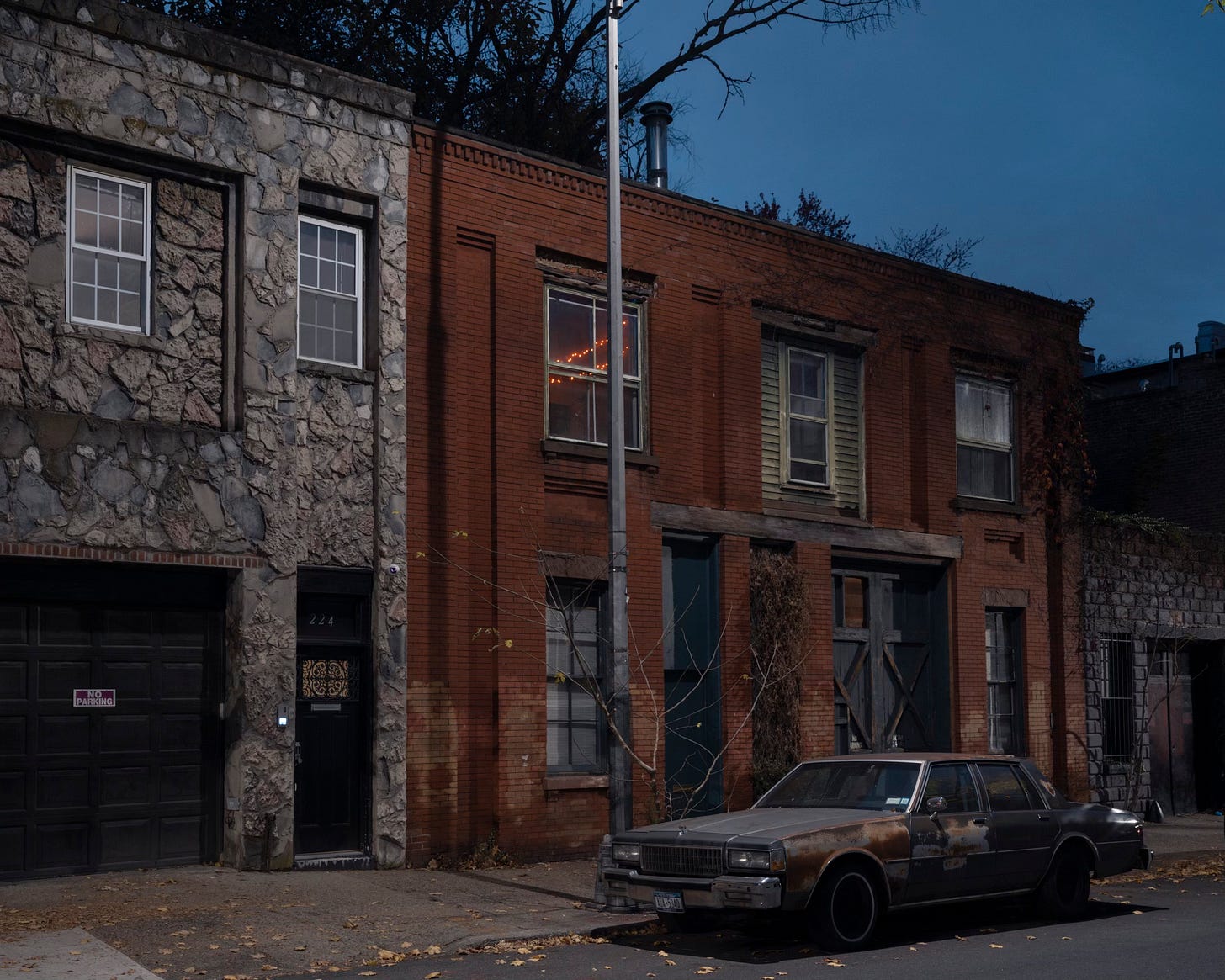

While the Brooklyn Enigma was once the most famous resident of Clinton Hill, her fame was eclipsed in the early 1990s by the man with more nicknames than Mollie Fancher had personalities. Christoper Wallace, aka Biggie Smalls, aka Biggie, aka Notorious B.I.G., aka Big Poppa, was raised by his mom, Voletta Wallace, at 226 St. James Place.

He went on to become one of the greatest rappers of all time. Smalls was killed in a drive-by shooting in Los Angeles in 1997. He was just 24 years old. His only two LPs, whose titles eerily bookmarked his death, were Ready to Die and Life After Death, which came out just 16 days after his murder.

In 2019, the corner of St. James Place and Fulton Street was named "Christopher Wallace Way."

In a sign of how the neighborhood has changed, the "one-room shack" that Biggie rapped about in his hit single "Juicy" was recently listed for rent at $5,100.

Here is some footage from the funeral procession through Clinton Hill on March 18, 1997.

I’ve added a part 2 to this one, which is more of an architectural tour of the neighborhood if you want to check it out here:

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording includes some house sparrows, a kid wielding a trombone, much to the delight of her fellow playground occupants, and the church bells from Queen of All Saints Church, technically in Fort Greene but audible from several blocks away.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

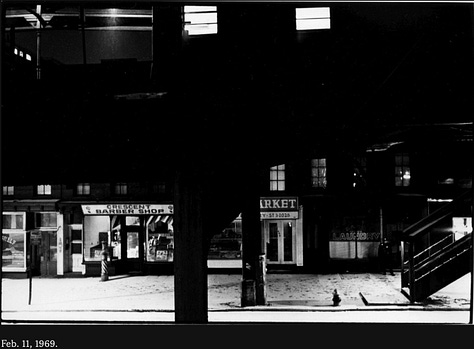

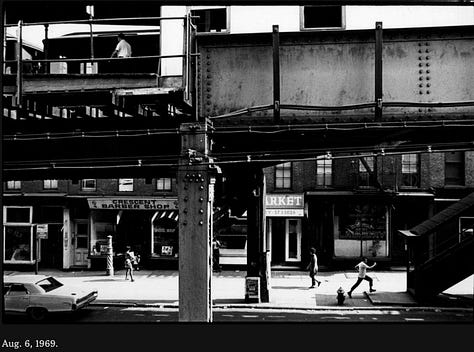

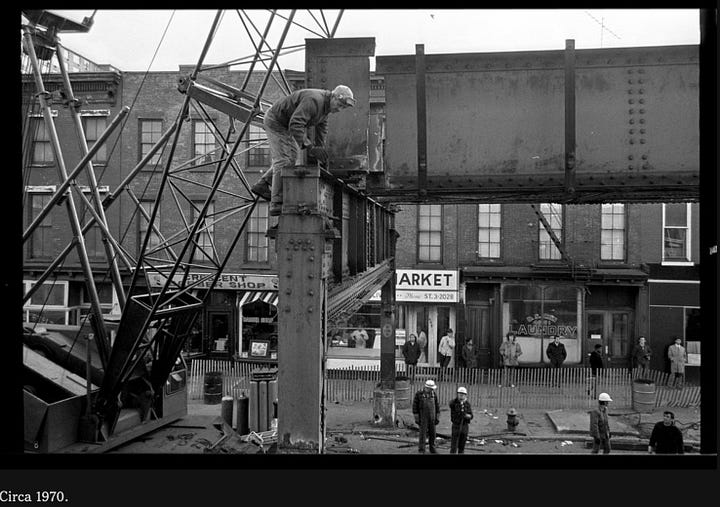

This week, I’m sharing the work of photographer William Gedney, a longtime Clinton Hill resident who made a series of images from his window on Myrtle Avenue. Gedney was a student at Pratt in the 1950s and returned to teach at the college in 1969.

By the time he was hired, he had received a Guggenheim Fellowship and had just had a one-person show at MoMA. Though Gedney was well respected among his peers, he was relatively unknown, and the MoMA show was the only solo show the photographer would have had during his lifetime. He passed away in 1989 at just 56 years old due to complications from AIDS.

These pictures were taken from his second-story window at 467 Myrtle Avenue, between neighborhood stalwart Kum Kau and newcomer Indulge Kitchen Supplies. The series, taken between 1969 and 1972, documents the dismantling of the Myrtle Avenue Elevated train.

In addition to the photographs, Gedney filled two journals with maps, observations, and quotes from other notable Clinton Hill Residents, such as Henry Miller and Walt Whitman, whose writing greatly influenced his work.

Dear reader, you must see Myrtle Avenue before you die, if only to realize how far into the future Dante saw. It is a street not of sorrow, for sorrow would be human and recognizable, but of sheer emptiness: it is emptier than the most extinct volcano, emptier than a vacuum, emptier than the word God in the mouth of an unbeliever.

Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn

I would love to get my grubby mitts on those notebooks, but Duke University administers his archive and seems to have a very strict usage policy. I got all these photos from a fantastic 2012 NY Times piece on Gedney and this particular project. Duke's archives, which contain work spanning his entire career, can be visited here.

NOTES

You can get an inside view (and some history) of the John Arbuckle house courtesy of Eden from Big City Little Friend, who recently cat-sat in the former coffee magnate's house.

Best slice in Clinton Hill: Luigis

Best plate of Gnocchi Alla Fonduta served in a former pharmacy: Locanda Vini e Olii

Best spot for T-bone steak, cheese eggs & Welch’s grape at 2 AM: Country Diner (if you don't know, now you know).

Next week is Thanksgiving, so I won’t be writing about a new neighborhood. I plan to send all subscribers my regular Monday bonus edition since I have a few items I couldn’t fit into this lengthy write-up. You’ve been warned!

*And here it is:

Clinton Hill - Bonus

Since I am not sending my regular newsletter on Thanksgiving day, I am making the bonus newsletter I send out to paying subscribers every Monday available to everyone. The bonus typically features an extra edit of photos from the previous week's neighborhood and an occasional anecdote or map that didn't make it into the main write-up.

This is always the best email I receive each week that isn’t written by a loved one. And this is my hood, so extra special this week.

MY HOOD <3