New Dorp is one of Staten Island’s oldest neighborhoods, though few traces of its early history remain. Located on the South Shore, just west of Midland Beach, New Dorp climbs nearly 400 feet from the edge of Raritan Bay to the base of Todt Hill, the highest natural point in New York City, where it meets the neighborhood of Lighthouse Hill.

Like much of Staten Island, the neighborhood was transformed by the opening of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in 1964. Then-borough president Albert Maniscalco welcomed it as a sign that “we are now on our way to surmounting the barrier of isolation.” Other Staten Islanders weren’t so excited.

This new connection to Brooklyn jump-started a wave of development that transformed the formerly sleepy enclave. Modest bungalows that had lined the coast, remnants of New Dorp’s time as a seaside retreat, were razed by Robert Moses to make way for Shore Front Drive, a waterfront highway meant to run from the Verrazano Bridge to Great Kills Park. The road was never built, but the damage had been done.

Then came Hurricane Sandy. In 2012, with a ruthless efficiency that would make Robert Moses jealous, the superstorm laid waste to the New Dorp coast, carrying away entire blocks and inundating parts of the neighborhood under six feet of water.

In the aftermath, the city bought many of the most severely damaged properties and auctioned them off with the provision that they be built to certain storm-resilient specifications. Similar to Ramblersville and Midland Beach, New Dorp’s rebuilt shoreline is marked by its peculiar architecture, the former single-story bungalows now suspended over their foundations with enough room between to accommodate the inevitable future storm surge.

Despite the ever-present threat of flooding, New Dorp has attracted new residents, including a growing Chinese population drawn over the bridge from South Brooklyn in search of affordable housing. Today, it has one of the city’s fastest-growing Asian populations, with census data citing a 180% increase in recent years, nearly five times the citywide rate.1

Nieuwe Dorp

The neighborhood's name comes from the Dutch, meaning "new town" or "new village." The Dutch, along with a smattering of Walloons and Huguenots, had originally settled Staten Island in Oude Dorp (Old Town), but frequent raids by the local Munsee tribe pushed them to seek safer ground. By the time the English seized New Amsterdam in 1664, the European settlers had already moved a few miles down the road to what they called Nieuwe Dorp.

The new village fared considerably better than the old, and soon attracted the first of many Vanderbilts, a family that would play a prominent role in the area's history and whose ties to New Dorp endure to this day. Jacob Van Der Bilt and his wife Neiltje were the first members of the now-famous family to settle on Staten Island, on land purchased in the late 1600s by Jacob's father, Aris. Another Vanderbilt ran the Rose and Crown Tavern, a lively watering hole built in 1665 that later served as headquarters for British Commander-in-Chief William Howe during the Revolutionary War. It was said this was where Howe read the Declaration of Independence, hot off the presses, to his officers. A small bronze plaque mounted in a scruffy triangle of grass in front of the Convenient Food Mart commemorates the site.

Jacob's son Cornelius lived a modest life as a farmer, but it was his grandson—also named Cornelius—who became the infamous Commodore Vanderbilt. He parlayed his skill piloting a simple, flat-bottomed, two-masted periauger between Staten Island and Manhattan into what would become a vast and lucrative transportation and shipping empire.

The Commodore had little faith in his eldest son, William, whom he frequently called "Blockhead" or "the Blatherskite." In 1855, after William suffered a nervous breakdown, the Commodore relegated him to running a 186-acre farm in New Dorp. To his surprise, William turned a profit, and the elder Vanderbilt's opinion of his son began to shift. Back in his father's good graces, William moved to Manhattan, marking the last time a Vanderbilt would live on Staten Island full-time.

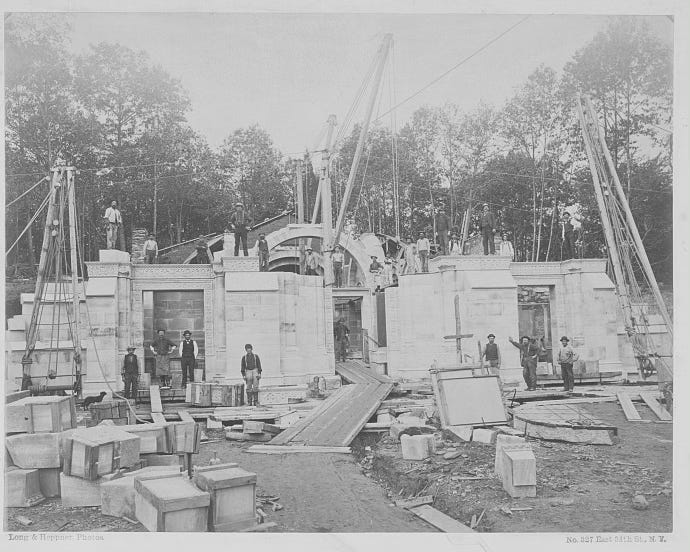

In the end, though, many of the Vanderbilts have returned to New Dorp. In 1883, William, who had also managed to double his considerable inheritance, commissioned the Vanderbilt Family Cemetery and Mausoleum, a private 16-acre property adjacent to the Moravian Cemetery, which is the oldest and largest active cemetery on Staten Island.

Vanderbilt hired Gilded Age "starchitect" Richard Morris Hunt (who also designed the entrance to the Metropolitan Museum and several Vanderbilt mansions) and landscape maestro Frederick Law Olmsted to design the grounds. The project was completed in 1886, one year after William's death, and has been described as "an extraordinary monument to America's Gilded Age."

The cemetery is private and still maintained by the Vanderbilt family. Sneaking through a fence in the adjacent woods and visiting the Vanderbilt tomb is something of a rite of passage for Staten Island teenagers.

At this point, you may be wondering if I, several decades past my teenage prime, threw caution to the wind and attempted to squeeze myself through this tantalizing, forbidden portal in the woods. That’s a story for another day. (Monday).

NILLA VILLA

The Vanderbilts weren't the only notable New Dorpians. Take, for example, the German confectioner Gustav A. Mayer. In 1899, Mayer, who had made a killing in wafers and had a factory in Stapleton, moved to New Dorp. The house he moved into, a two-and-a-half story Italianate villa with a wrap-around porch and a cupola with a commanding view of Raritan Bay, occupied the same patch of land as the former Rose and Crown Tavern, which had been demolished in 1855.

Mayer's biscuits were highly sought after, gobbled up by the discerning diners of legendary Manhattan restaurants like Delmonico's. Besides making the cookies themselves, Gustav also had the wafer mold market cornered, patenting designs like the Vienna Roll, Cigaretta, Carlsbad, and Virginia Sugar. Not one to rest on his laurels, he also developed his own birch beer, patented a room humidifier, and made sparkling tin Christmas ornaments that sold like hotcakes.

Gustav's real claim to fame, though, was the Vanilla Wafer, the slightly mounded, quite dry yellow cookie made from flour, sugar, shortening, eggs, and, of course, vanilla. While that really doesn't seem like much of a recipe, Nabisco's R&D department was nothing to write home about, so they were happy to pony up for the rights to the wafer.

Vanilla wafers didn't really come into their own until the 1940s when Nabisco began printing recipes for banana pudding on the back of each box. The recipe, which starts with a generous layer of wafers on the bottom, was a hit with people who like beige desserts and hate to cook. Interesting fact: According to Wikipedia, Nilla Wafers are "commonly used to facilitate the oral administration of various compounds or medications to rats in testing."

Gustav died in his home in 1918, leaving it to two of his daughters, Paula and Emilie. The two sisters never married and, in later years, never left the second floor of the house, prompting some people to call it the Grey Gardens of Staten Island. They used an elaborate pulley system to receive groceries, mail, and laundry from below. Both lived to be over 100 years old.

The building was purchased in 1990 by Staten Island photographer Bob Troiano. The ground floor has been renovated, but the second floor, complete with faded murals painted by Paula, is kept in a state of “controlled decay,” making it a favorite backdrop for fashion shoots used by photographers like Steven Meisel, Peter Lindbergh, and Tom Corbett.

Today, you have the chance to “complete the next chapter in a true American masterpiece,” and buy the Gustav A Mayer house for 1.6 million dollars. This listing has lots of pictures of the interior and a good summary of the building’s history

TAKE THE LOAD OFF FANNY

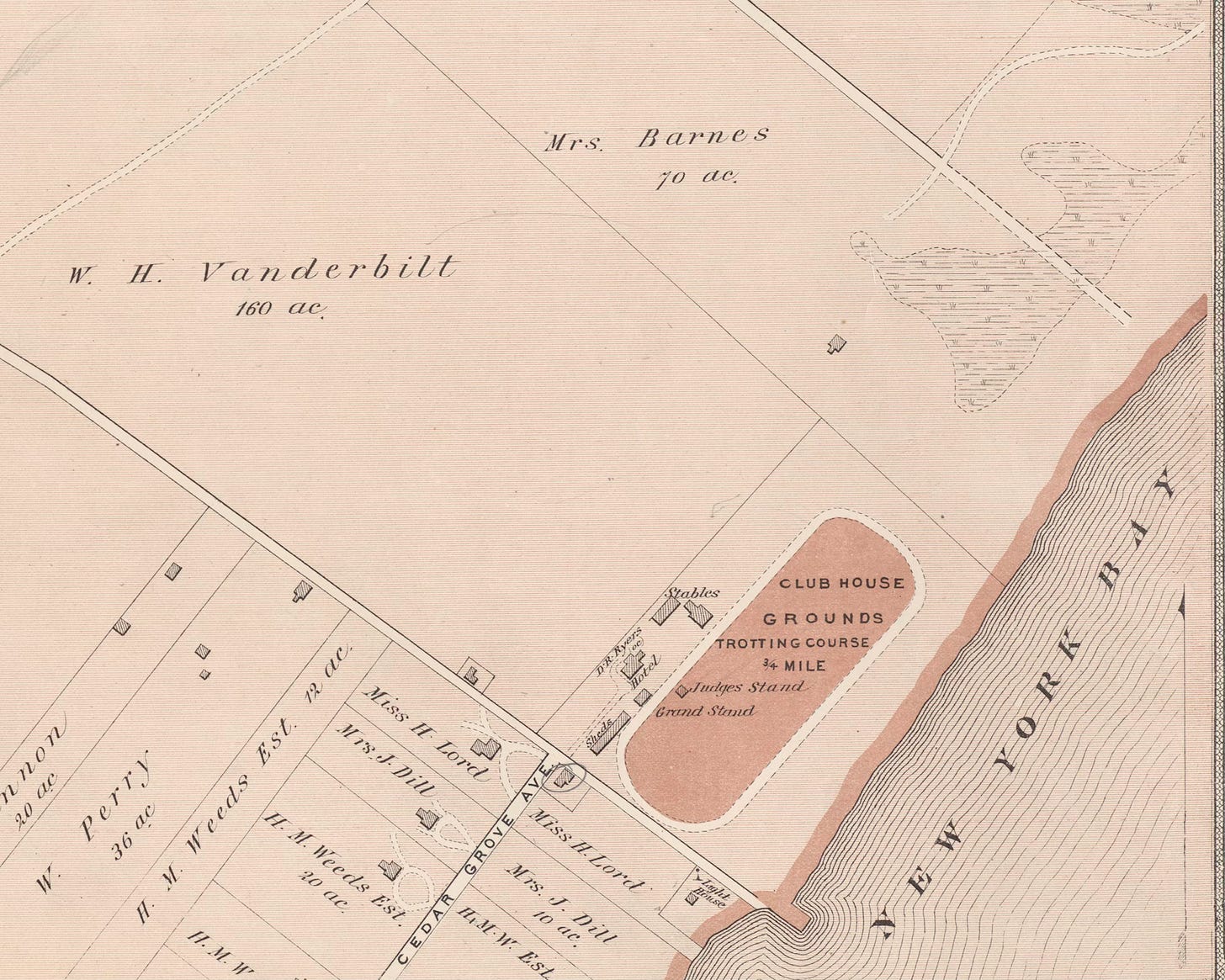

Meanwhile, down at the shore, things were getting interesting. The horse racetrack William Vanderbilt had built on the edge of his farm started to attract visitors to New Dorp, as did the pristine waters and cool ocean air.

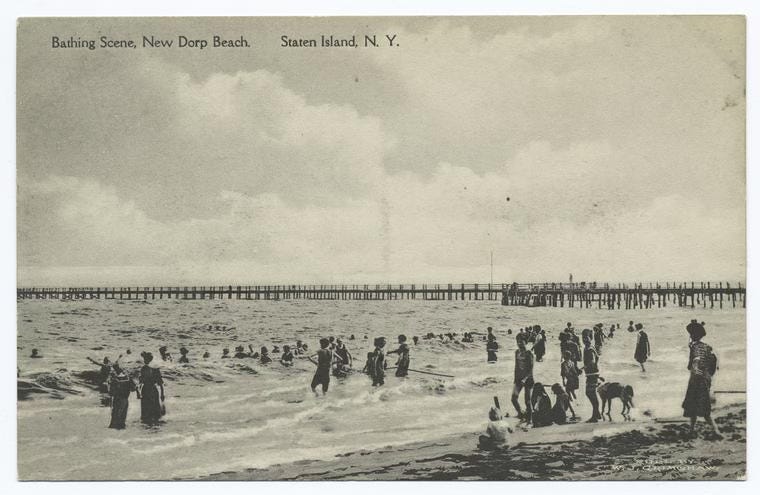

By the turn of the 20th century, the area had become a fashionable seaside destination with several hotels like Lang's, Munger's on the Beach, and Edward Hett's New Dorp Beach Hotel lining the long, wide beach.

One of the more memorable events in New Dorp's history occurred on the beach right in front of Edward Hett's hotel early on June 4th, 1904.

An eyewitness, identified only as a “Truthful Staten Islander,” was relaxing with friends when one of them suddenly turned pale, raised a trembling finger, and uttered just two words: “Sea Serpent!”

The credibility of this eyewitness was slightly undermined by his admission that he’d spent the previous evening “drinkin’ some o’ Harry Stevens’s liquid extract of third rail,” and that he might’ve had a case of the “William James Jams.” Still, he swore he saw what one of his companions described as a “blood-sweatin’ behemoth” emerging from the surf. This friend, notably, had traveled with the circus, making it all the more surprising that he failed to recognize the creature for what it really was, an elephant.

Two days earlier, three elephants from the Great Durbar of India show at Luna Park in Coney Island had escaped. While the two males were quickly recaptured, the third, a 3-ton female known as either Fanny or Alice, depending on the newspaper, had vanished. She swam across Raritan Bay and came ashore in New Dorp.

After spending the night in the local police station, where she devoured a week’s worth of hay, Fanny was finally retrieved by Coney Island elephant handler Pete Barlow. He coaxed her into a waiting van and onto a ferry bound for Manhattan. But the commotion of honking horns and churning engines agitated Fanny’s “gentle sensibilities,” so her handlers administered a calming cocktail of whisky and cocaine, which she reportedly drank with “apparent relish.”

Plenty of people doubted that the elephant had actually made the long swim and instead suggested she had been ferried over and dropped just offshore as part of an elaborate marketing scheme.

I did find an article about a strikingly similar incident the following year, also involving Pete Barlow, who had taken his "Barlow's Elephants" show on the road. The trainer and his four elephants arrived at a Virginia amusement park (coincidentally also named Luna Park) on August 20, 1906. That very night, the four elephants — Annie, Jennie, Queenie, and Tommie— escaped and spent the week laying waste to cornfields, barns, and graveyards.

Eventually, with the help of Wild West Showman Pawnee Bill, the elephants were all corralled back. These two incidents suggest that Barlow was either a genius marketer or a terrible elephant wrangler. Perhaps both.

MILLER FIELD

After William Vanderbilt died, his son, George Washington Vanderbilt, inherited the New Dorp Farm. He built a large mansion on the edge of the property near the shore, where he stayed periodically until his death in 1914.

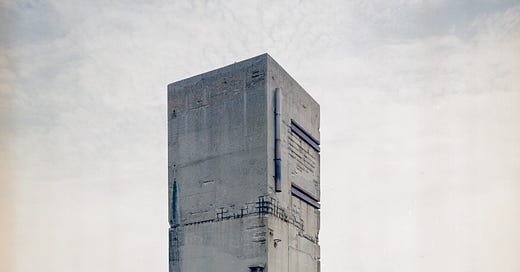

In 1919, the Vanderbilt heirs sold the property to the federal government, which transformed it into Miller Field—the eastern Seaboard's only coastal defense air station. The military facility featured a grass runway, seaplane ramps extending into the bay, and four hangars. It remained operational until 1969, when the base was decommissioned.

Ironically, Miller Field became more famous for a catastrophic plane crash than for any aircraft that took off from its runways. On December 16, 1960, two commercial airliners—United Flight 826 and TWA Flight 266—collided in midair over Staten Island.

The TWA Constellation plummeted into Miller Field, while the United DC-8 crashed in Brooklyn's Park Slope neighborhood. The disaster claimed 134 lives, including six on the ground, making it America’s deadliest aviation accident at that time.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio features the sound of an incoming thunderstorm, some post-school hijinks, a fog horn, and the sounds of Raritan Bay.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

All this talk of escaped elephants of course made me think of Joel Sternfeld's image "Exhausted Renegade Elephant, Woodland, Washington" from his "American Prospects" series.

An Art Forum review of a show of Joel’s “post-Pop landscapes” describes the image:

It’s a jarring image that may look staged or Photoshopped to an eye nourished on Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson and his spawn. But no: It’s just that Sternfeld has a knack for homing in on improbable situations, and his lucid, hieratic style, which suggests the gaze of an omniscient narrator, heightens the pictures’ resemblance to fiction.

Joel, whose work I’ve featured here and here, needs no introduction. Besides being an amazing photographer, he is also a gifted storyteller. Lately, Joel has been sharing some of the stories behind his photographs on Instagram. I’m reposting this excerpt (with his permission) describing the circumstances behind the iconic photo:

As I headed north on Interstate 5 I turned on the radio, my principal source of news: an elephant had escaped from a training farm in the hills west of Mt. Helens and had gone on rampage. My first impulse was to not go but it was right on my route and I couldn’t resist so I dutifully pulled off the highway.

With the radio’s instructions it was fairly easy to find the road on which the now captured elephant was being led back. His trainer, Morgan Berry, had died the previous evening, most likely of a heart attack. Thai was reluctant to follow anybody but Mr. Berry and so a female elephant was brought in to lure him back—to little avail.

I found what I believed would be a safe spot– as Thai and his failed seductrix passed I made a picture.

Then Thai, hot, traumatized, tranquilized and exhausted collapsed in the road. A boy got out a bucket of water and tossed it. As he did so I photographed again.

What happened next I can only describe: the elephant and all the handlers who had been up all night, went to sleep in the road. Only the sheriff and I were awake, but I was out of film.

Working 8x10 at the rate of two negatives a day is a dance—but it does force you to establish a fairly precise hierarchy of your interests. And if it doesn’t make you crazy, it can make a photographer of you.

I so love hearing the backstory of this image, and the last quote is particularly apt in this day of “spray and pray” photography. (See also Janelle Lynch’s recent essay in Andy Adam’s newsletter.)

Sidenote: Perhaps I was being a little too harsh on Pete Barlow’s wrangling skills up above. It seems like elephant escapes are a rather frequent occurrence, including this incident in Butte, Montana just last year. In any event, I think we can all agree that the world would be a better place if elephants weren’t put in situations from which they needed to escape.

ODDS AND END

Last week, I was thrilled to learn that I’ve been awarded an O’Shaughnessy Fellowship in support of The Neighborhoods. The fellowship will allow me to continue developing this project and expand its scope with an interactive website and, hopefully, a book (or five).

I recently passed the two-year mark, got my 10,000th subscriber, and, next week, will be covering my 100th neighborhood. Those are all numbers I couldn’t fathom when I started, but I realize I’m only about a third of the way to my goal of photographing and writing about every neighborhood in the city. This fellowship is a huge boost. I’m so grateful to OSV for their support, and to all of you who’ve followed along and taken an interest in this project, making this long (and still growing) journey possible. Thank you!

Nabisco isn't the only player in the vanilla wafer space. Keebler also offers their own variations of the classic treat, none more questionable than the Rainbow Vanilla Wafers introduced in 1999. In a bold departure from the wafer’s traditional golden hue, these colorful cookies featured enough artificial dyes to make RFK Jr. want to hide another dead bear in Central Park.

When a Fortune magazine reporter asked Carolyn Burns, Keebler's marketing director for cookies, how consumers were responding to the rainbow makeover, she said they had received no negative feedback on the unusual coloring. "And frankly," she acknowledged, "I'm surprised."

New Dorp even has its own theme song—2015’s New Dorp. New York, a collaboration between English producer SBTRKT and Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig.

Flag flappin’ in Manhattan

New Dorp, New York

Gargoyles gargling oil

Peak of the empire, top of the rock

I have no idea what those lyrics mean, but hey, at least they’ve got their own song.

Which reminds me, did you know that there is a record inspired by this newsletter? Last year, longtime reader Will Cruttenden released “The Neighborhoods” under the name Mexican Jets. Will tackles songs covering neighborhoods from Graniteville to Throgs Neck with lyrics that actually make sense. You can check it out here.

If you are on the fence about visiting the neighborhood, you should know that New Dorp has the borough’s only Alamo movie theater, a wealth of bubble tea spots, and a legendary comic book store, JHU Comics, which has been in business since 1983.

https://projects.thecity.nyc/12-hours-new-dorp-staten-island/

One of my favorite Staten Island neighborhoods, which still has an active shopping strip along New Dorp Lane near the railway station. Funny that the old Shop Rite in New Dorp doubled as post-Armageddon Los Angeles (Super Duper Mart!) in Amazon's excellent "Fallout" television series. Staten Island plays so many different towns in film and TV, but rarely plays itself. Most shows set on SI are filmed elsewhere for some reason.

I grew up on Long Island right around the corner from the LI Game Farm. They used to do face painting there for Halloween and around Christmastime you could feed little pellets to reindeer, so I have a lot of nice memories. But also, animals were constantly escaping; I would routinely run into errant peacocks while riding my bike. One day I noticed "Lost Giraffe" signs taped up around the neighborhood because apparently the farm's giraffe had escaped. The giraffe was found a few days later but I've always wondered, how the heck do you lose a giraffe??

Anyways - congrats on the fellowship and upcoming milestones!