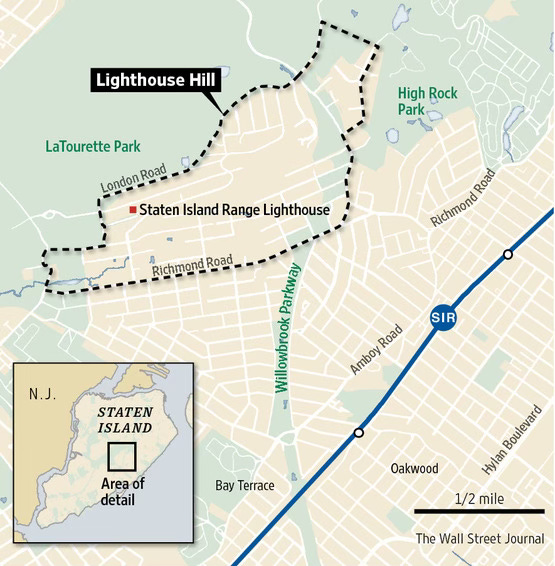

Lighthouse Hill - Staten Island

Frank Lloyd Wright, Lucky the Leprechaun, and the Dalai Lama walk into a Lighthouse...

As far as neighborhoods go, Lighthouse Hill punches above its weight. Not only can it boast its namesake lighthouse, but the diminutive Staten Island community is also home to the only Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home in New York City and even has its own Tibetan Art Museum. Not bad for a neighborhood that the Village Voice described as “barely larger than an IKEA parking lot.”1 Actually, that article refers specifically to Egbertville, a name that seems to be used interchangeably with Lighthouse Hill. Since Egbertville doesn’t even garner a mention on the crowd-sourced NY TIMES neighborhood map, I’m sticking with the more evocative Lighthouse Hill.

Forest Hill Road to the north, Richmond Road to the south, Rockland Avenue to the east, and La Tourette Golf Course to the west make up the neighborhood’s borders. Lighthouse Hill abuts the Staten Island Greenbelt.

A VERY SENSUAL LIGHTHOUSE

I first learned of Lighthouse Hill after buying this Percy Loomis Sperr negative on eBay.

I have been collecting Sperr’s negatives for a while, revisiting the corners of the city where he had photographed. From the early 1920s until the early 1940s, Sperr was the official photographer for the New York Public Library. When researching this particular photo, I was surprised to learn that the Staten Island Lighthouse, first lit in 1912, was still operational.

“Tonight, for the first time a great white ray of 300,000 candlepower will bore a hole through the gloom seaward.

Once you get to Lighthouse Hill, it’s hard to miss the 90-foot octagonal tower looming above the detached single-family homes surrounding it. A 1968 report from the Landmarks Preservation Commission says, “One would sooner expect to come upon this picturesque lighthouse on the rocky coast of New England than within the boundaries of New York City.”

The lighthouse (one of six on the island) is what’s known as a range lighthouse. It works in tandem with another shorter lighthouse at the water’s edge. When a ship’s captain lines up the two lights vertically, they know they are navigating the channel correctly. The short end of the pair is the West Bank Light, situated in the middle of Ambrose Channel at the entry to New York Harbor.

The West Bank Lighthouse was automated in the early 1980s, and in 2007, the lighthouse structure was deemed “excess” by the Coast Guard and put up for auction. Sailor and historic building enthusiast Sheridan Reilly bought it for $195,000.

A 2009 New York Times article about the gradual automation of the city’s lighthouses lamented the pending extinction of the entire profession of lighthouse keeping:

A lighthouse without a crabby old man inside is basically a barn without a heifer, a Continental restaurant without an oily maître d’. The whole point of a lighthouse is to offer isolation to those who need it most to give the bitter old coots of the world a place to find some peace.

“Lighthouse Legend” Ed Burdge, the first keeper of the West Bank Light, would have taken exception to the Times’ depiction of lighthouse life as a peaceful escape (not to mention his characterization as an old coot).

A lighthouse is about the noisiest place in the world. Out there on West Bank, for instance, with a gale blowing. When I was there the tower rose right out of the water, with no footing at all around it, so the waves crashed against the whole tower; shook it until sometimes the mantles over the burners in the light broke. Sometimes the waves went clear over the gallery, and the spray over the light itself.

Forty or sixty tons of water, driven by a fifty-mile gale, racing in with the tide and slamming against a solid tower of stone and iron makes it about as quiet as when two railroad trains butt each other head on. Down at the floor level, there is a gas engine pounding away, with the exhaust exploding outside, the iron plates in the tower groaning, the fog siren screaming, and the bell ringing, and up in the light a stream of kerosene burning under a hundred pound pressure, and roaring louder than the gale.2

Interestingly, though it is inaccessible to the public, the West Bank lighthouse has garnered 16 reviews on Google with an aggregate score of 4.8. Jordan Levine claims, “ It doesn’t get any better than this,” while Gavin Webster takes it a bit further in his review: “Excellent job, very sensual lighthouse.” We’ll have to take Gavin’s word for it.

From Lighthouse to Wright house

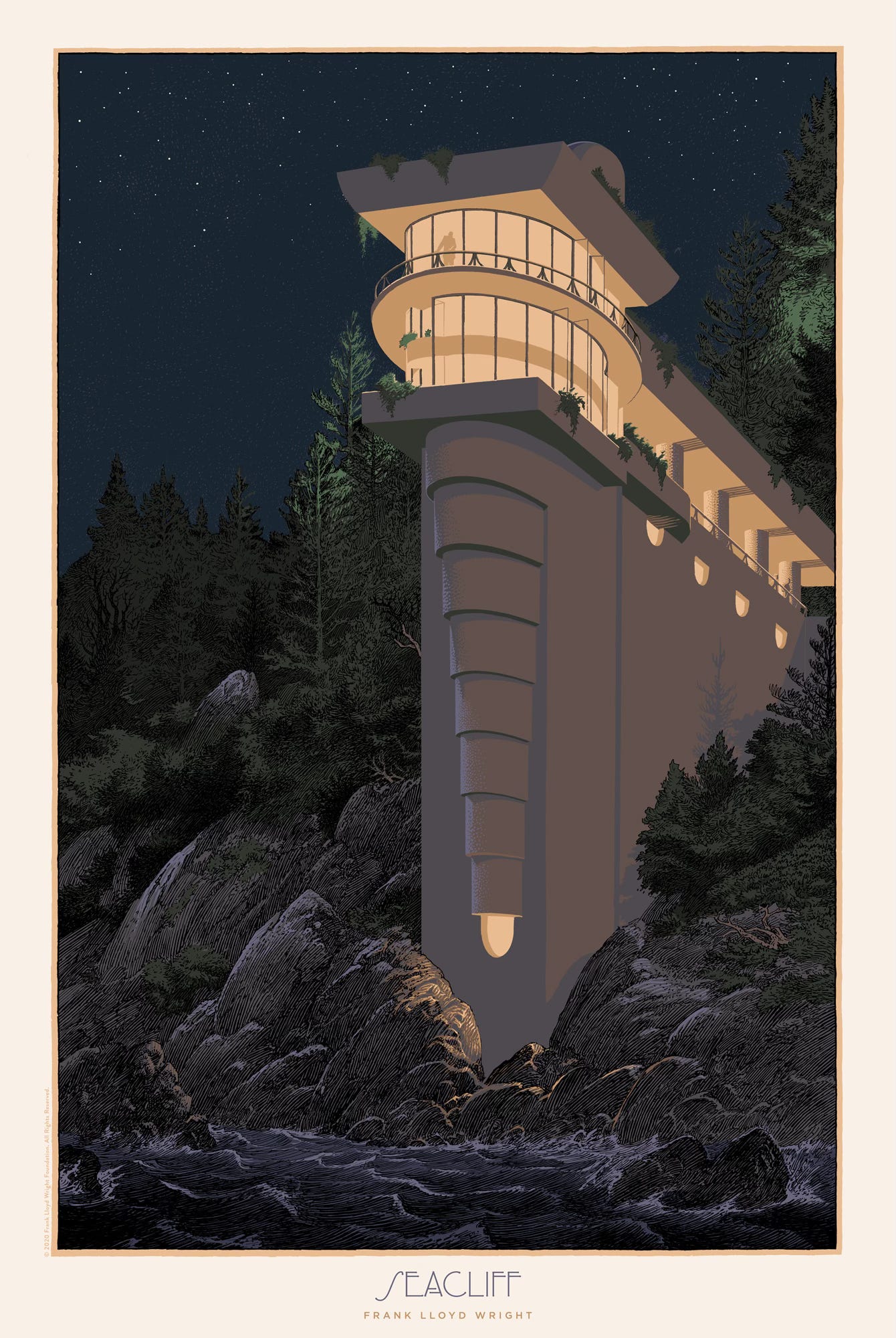

The closest architect Frank Lloyd Wright ever got to designing a lighthouse was his never-realized Seacliff project overlooking China Beach in San Francisco. The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house closest to a lighthouse is in Lighthouse Hill.

Wright was no fan of cities, once saying his time in NYC was like “dying a hundred deaths a day on the New York gridiron in the stop-and-go of the urban criss-cross.” Don’t sugarcoat it, Frank.

His animosity, however, didn’t get in the way of his designing the Guggenheim Museum, one of the city’s most iconic buildings. When the Mercedes-Benz showroom Wright designed at 430 Park Avenue was demolished in 2013 to make way for a TD bank, that left only one other Frank Lloyd Wright building in all the five boroughs. Given his distaste for the “medieval atrocity” of the Manhattan skyline, perhaps the remote neighborhood in the middle of Staten Island with a commanding view of the Raritan Bay was the perfect place for one of his designs.

The house, christened Crimson Beech after a copper beech tree (now dead) in the front yard, was officially known as Prefab No. 1. It was part of a collaboration between Wright and architect/contractor Marshall Erdman.

Wright “strongly believed that the average American was entitled to a home that could also be a work of art.”3 He concluded that the only way to achieve that goal was through the economies of scale made possible by prefabrication.

William and Catherine Cass, who had recently bought a piece of property in Lighthouse Hill, wrote to the architect after seeing him in this remarkably smokey interview by Mike Wallace. (5/5)

Within months, their new home was speeding across the country, on its way from Madison, WI, borne on the beds of four tractor-trailers.

The Casses paid an astonishingly reasonable sum of $20,000 or about $217,000 in 2024 dollars for the house. Then, the contractors got involved. The bill ballooned by an additional $35,000 exposing the fatal flaw in this plan to make high design available for all.

Wright, a notorious micro-manager, dictated every detail of the house’s interior design. Catherine Cass: “He was a real tyrant, he never took anyone else into consideration. He chose the furniture, the fabric, even the paint colors for us.”4

Though he was supposed to visit Crimson Beech, Wright never saw the house as he died less than a year after its completion. The Casses sold the house, now a national landmark, in 1999.

Here are some pictures of the no longer original interior. And here is another beautiful example of one of Wright/Erdman’s prefab number one designs just north of the city.

SOUND BATH

Amazingly, neither a 90’ lighthouse nor a Frank Lloyd Wright prefab is the neighborhood’s most unique attraction. That distinction arguably belongs to the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art.

Jacques Marchais was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1887. Shortly thereafter, at the age of 3, she began working as a child actress. Jacques was married twice before finally settling down in 1920 with Harry Klauber, owner and president of the Klink Chemical Corporation. A year later, they moved to Staten Island.

In 1938, she opened a gallery of Indian and Tibetan art on the Upper East Side (40 East 51st St) and used the profits and connections to build a collection of Tibetan art and artifacts. Using some photographs of the Potala Palace in Lhasa as inspiration, Jacques began to build a home for her art.

One can only imagine what the neighbors thought of the woman named Jacques building a replica of a Himalayan monastery in the middle of their rural Staten Island neighborhood. When asked that same question, her husband answered only, “I am in the chemical business.”

Last week, I decided to pay the museum a visit. After a quick perusal of their website, I saw they were offering something called a Sound Healing meditation, which seemed intriguing. I was lucky enough to book a last-minute appointment. Lighthouse Hill isn’t the easiest neighborhood to get to, so on a muggy spring day, I decided to make the drive from Brooklyn to Staten Island.

When I got to the museum, I realized there was no parking lot, and street = parking was prohibited on the residential street. I was forced to retreat to the bottom of the steep hill that gives the neighborhood its name and restart my journey on foot.

People need to climb the mountain not simply because it is there, But because the soulful divinity needs to be mated with the spirit.” ― Dalai Lama XIV

Wise words from His Holiness, but at this point, I was more concerned with the frunk™ of one of the many white Teslas, silently speeding up the sidewalk-less streets, mating with my torso than with the divinity of my spirit.

By the time I got to the museum, with one minute to spare before my appointment, I was a bundle of nerves drenched in sweat, more in need of an actual bath than a sound bath. The museum’s director, Nico, ushered me into the chanting hall filled with artifacts and thangkas, the air redolent of nag champa and yoga mats. A small crowd of already supine sound bathers gazed serenely up at the vaulted ceiling. I had some serious catching up to do.

Tip-toeing around my fellow bathers, I secured the last mat, thankfully situated at the back of the room. After taking part in a round of deep breathing exercises, I soon felt myself beginning to relax, the torrent of perspiration gradually slowing down to a trickle.

The next thing I knew, the leader of the meditation, who had somehow made it all the way to the back of the room without my noticing, whispered something that sounded vaguely like “take the bowl” right before placing a heavy brass bowl on my stomach and pressing it, with surprising force, down onto my abdomen.

I wasn’t sure if this was a punishment for my late arrival or standard operating procedure, but, like the well-adjusted grownup I am, I kept my eyes pressed tightly shut and pretended not to hear. As it turns out, it was good I didn’t try to “take the bowl” because immediately after whispering, she thwacked the side with some kind of mallet, unleashing a cascade of sound waves that resonated down through my furthest extremities. It was amazing. As the echoes of the initial hit died down, she hit the bowl again. I was now a sound bath convert.

For the next several minutes, our sound bather struck a variety of cymbals and bowls whose chiming overtones echoed throughout the room, each one the sonic equivalent of a stone being thrown in a pond. Even a minor freak gong incident did nothing to dampen the effects of the experience.

If you are curious about the museum, you should try to time your visit to coincide with one of the sound bathing sessions, which seem to be offered semi-regularly on the weekends. Maybe take the bus though.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s recording weaves between the Greenbelt and the Sound Bath, which the museum kindly let me record. It’s a little longer than usual, but I think it’s a good one.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Christian Fiedler, is a New Jersey-based photographer whose project, “Beacons Through Time,” uses pinhole cameras to document lighthouses on the Eastern seaboard. This article by Christian is an in-depth look at his process and results. Here is the solargraph, taken over several months, that he made of the Staten Island Range Lighthouse.

Besides being a photographer, Christian is a real Renaissance man whose other projects include:

An attempt to climb to the highest point in every US State.

A project making Gâteau à la Broche from scratch. The Gâteau à la Broche is a cake made of layers of batter deposited, one at a time, onto a tapered cylindrical rotating spit baked, rotisserie style, on an open fire.

Sending a high-altitude weather balloon loaded with arcade tokens into space, an endeavor that makes more sense if you know his cousin owns an arcade bar in Davenport, Iowa.

For more of Christian’s work, check out his website here

ODDS AND END

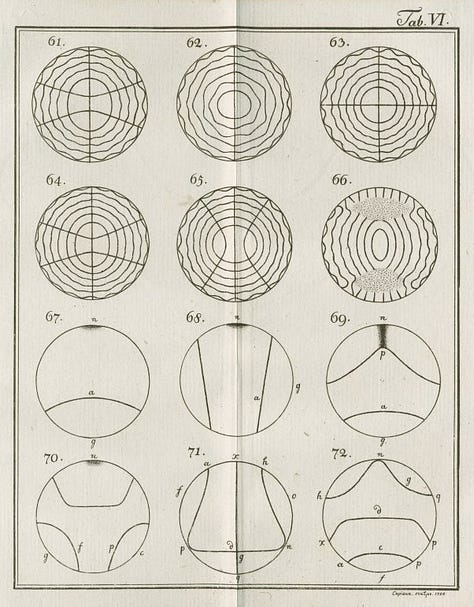

If you haven’t seen Kenichi Kanazawa at work, using sonic vibrations to create patterns called Chladni figures on a metal plate, do yourself a favor and watch this short video.

If you want to read more, Ted Gioia wrote a great post about Cymatics and Chladni figures.

Chladni figures While the West Bank lighthouse is technically closed to the public, I found a video of two guys exploring the lighthouse ten years ago with a small boat and some very questionable ornithology takes.

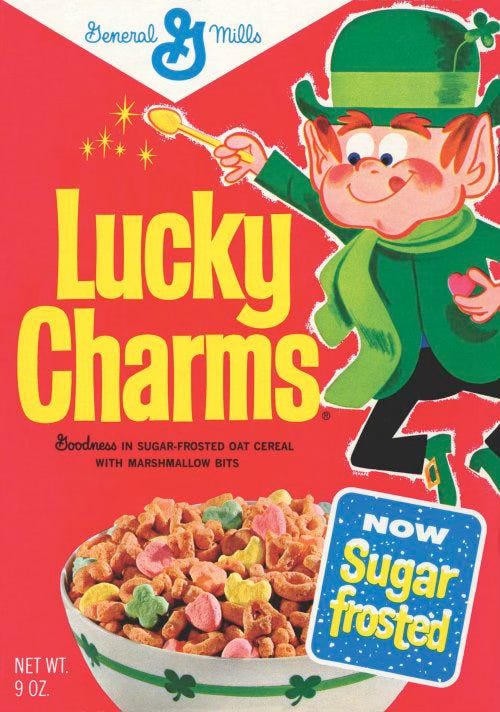

You may be shocked to learn that Lucky the Leprechaun was a fraud. For 29 years, starting in 1963, the voice of the impish elf extolling the magical deliciousness of his Lucky Charms belonged to Staten Island-born Arthur Anderson. Like Jacques Marchais, Anderson was a child actor and, like Marchais, lived in Lighthouse Hill.

Here is a rendering of that Frank Lloyd Wright lighthouse in Sea Cliff.

The house that was eventually built there was bought by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey in 2012.

https://www.villagevoice.com/close-up-on-egbertville-staten-island/

https://www.lighthousefriends.com/light.asp?ID=757

Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks. Frank Lloyd Wright Drawings: Masterworks from the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives. New York: Harry N. Abrams,Inc., 1990.

https://www.nytimes.com/1988/03/24/garden/one-wright-dream-on-staten-island.html?unlocked_article_code=1.t00.-bvr.l9PL0zZ6gsM7&smid=url-share

The star of this week’s issue: Jacques Marchais’s husband. We need more people like this!

I can't believe Frank Lloyd Wright designed an automobile dealership's showroom!