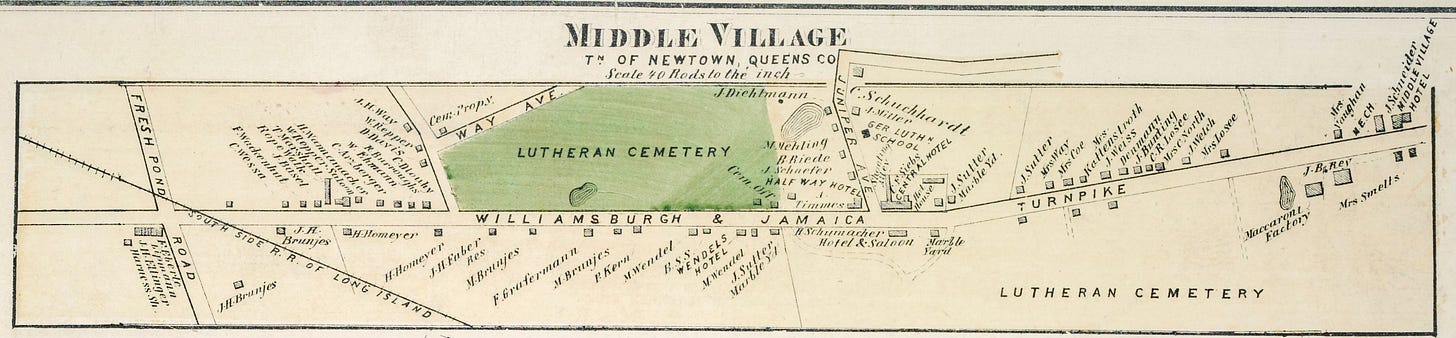

Middle Village sits, appropriately enough, in the middle of Maspeth, Glendale, Rego Park, and Elmhurst in Queens. The borders of the neighborhood are the Long Island Expressway, Cooper Avenue, Woodhaven Boulevard, and Mount Olivet Cemetery, one of several burial grounds in the area.

The name comes from its location at the midpoint of the Williamsburgh and Jamaica Turnpike (today’s Metropolitan Avenue), the route farmers used to travel between the ferry landing in Williamsburg and Jamaica, Queens.

Development was slow to come to the area, in large part due to the massive Juniper Swamp, which spread over 100 acres and into neighboring Maspeth. During the Battle of Long Island in 1776, American troops hid in the swamp’s dense of juniper and white cedar forest. Later, British soldiers occupied the area, cutting down most of the trees to build ships and fuel their fires. Once the timber was gone, residents and soldiers began harvesting the swamp’s 16-foot-thick peat deposits, cutting and drying the material to use as fuel.

Things remained quiet in Middle Village for the next 70 years or so, until the passage of the Rural Cemetery Act in 1847 which allowed commercial businesses to conduct burials for the first time. Coupled with a ban on internments south of 86th Street in Manhattan, the new legislation precipitated a land rush along the Brooklyn–Queens border. Vast burial grounds were established in neighborhoods like Cypress Hills, Blissville, and Glendale to absorb the overflow of the city’s dead.

Middle Village’s development was jumpstarted by its inclusion in this “cemetery belt.” Hotels and restaurants followed, catering to families visiting graves or city dwellers looking for a countryside escape from sooty, cramped Manhattan.

But the heart of the village, the land around Juniper Swamp, remained mostly undisturbed, a gloomy, muddy quagmire inhospitable to both the living and the dead.

DRAIN THE SWAMP

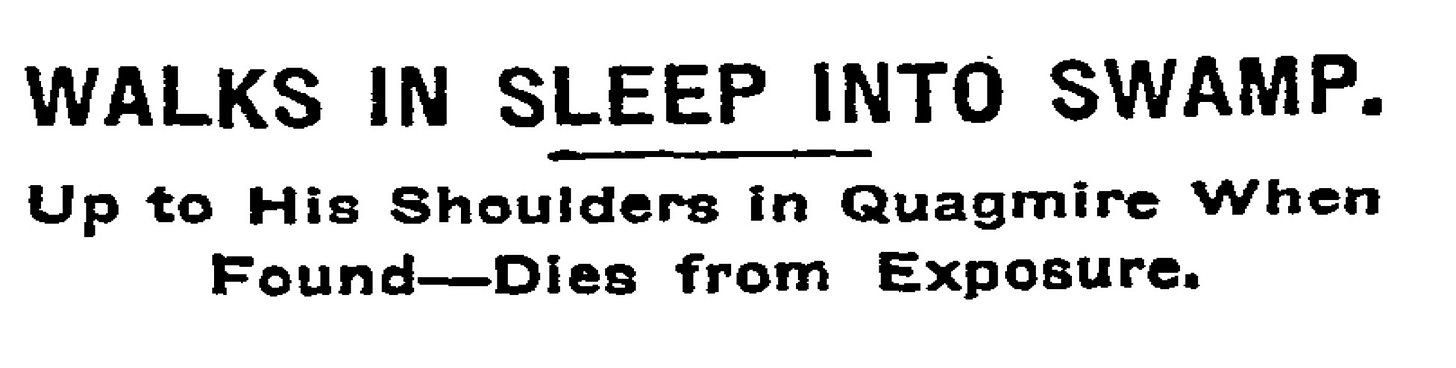

In 1904, 30 year old Clarence Smith made the unfortunate decision to book a room on the edge of the swamp. In the middle of the night, Clarence, who had a reputation for walking in his sleep, got out of his bed and wandered into the bog. The next morning, a passerby "saw a man's head and shoulders protruding from the mire," and a rescue was attempted. By the time they got Clarence to the hospital, he was dead. It was presumed that the swampy sonambulist had been woken from his slumber by the shock of the cold November water, but was too stuck to free himself, and died of exposure.

That was how the story appeared in the New York Times and the Brooklyn Eagle. A more lurid account in The Daily Standard Union, on the other hand, claimed Smith had been trapped in the swamp for ten days. His groans, it said, “could be heard by the whole neighborhood,” but he was so submerged no one could find him. The cause of death in the Standard Union account was starvation.

It wasn’t until 1916, when tracks were laid for the New York Connecting Railroad, that draining the swamp began in earnest. Some saw this newly reclaimed land as an opportunity.

PHANTOM VILLAGE

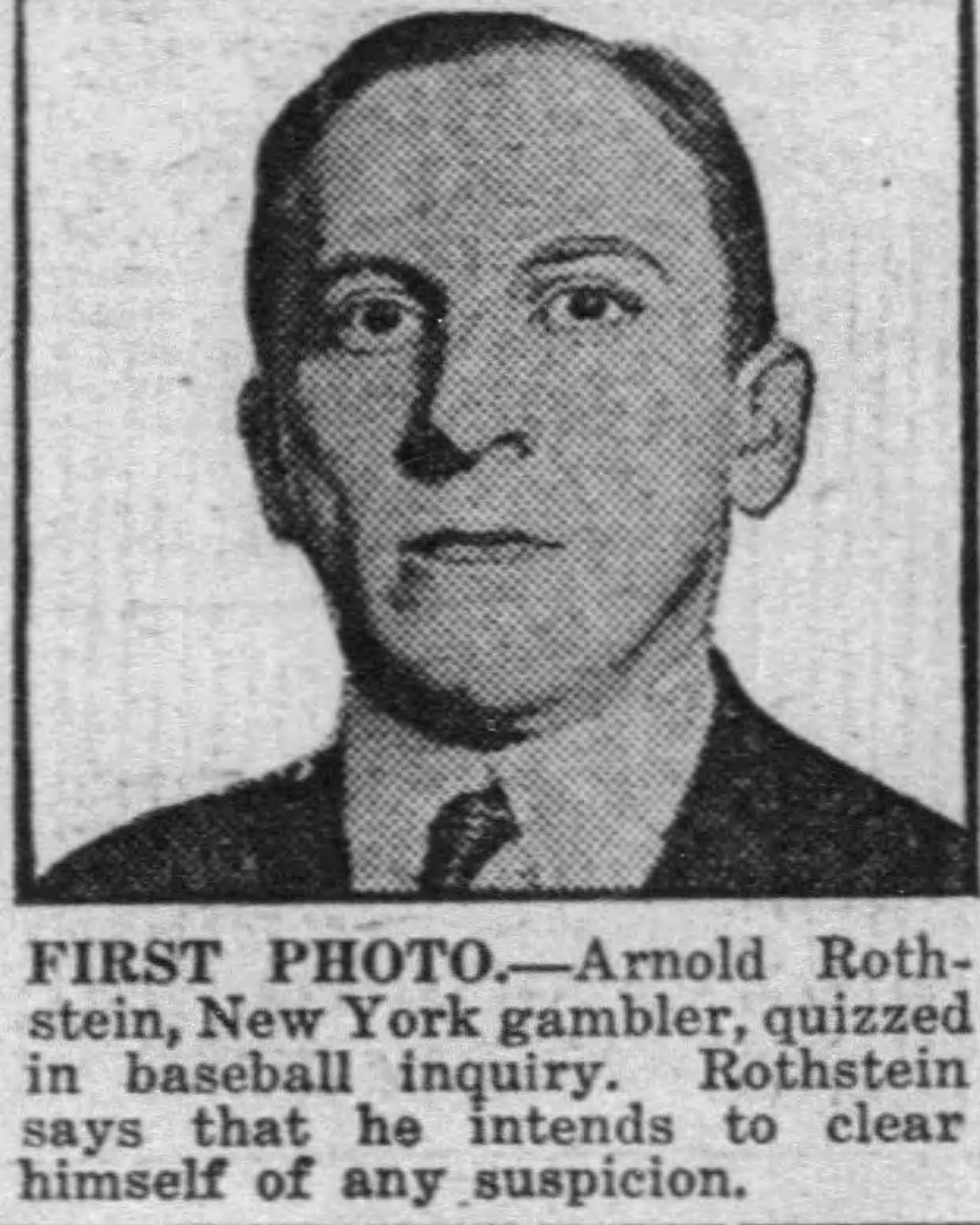

In the early twentieth century, Arnold Rothstein, also known as "the Brain," "the Big Bankroll," or simply A.R., emerged as a pivotal figure in early American organized crime and a powerful kingpin within New York's Jewish underworld. A compulsive gambler and shrewd businessman, his tactics and influence would shape the Mafia for decades.

During Prohibition, Rothstein led a high-end bootlegging empire, importing Scotch whisky directly from Scottish distilleries via his own transatlantic smuggling fleet.

Rothstein was also suspected of orchestrating the scheme that led eight Chicago White Sox players to intentionally lose the 1919 World Series. While his involvement was never definitively proven, he did make a killing betting on the underdog Cincinnati Reds and invested some of those winnings in Middle Village, purchasing 88 acres of the Juniper Valley Swamp.

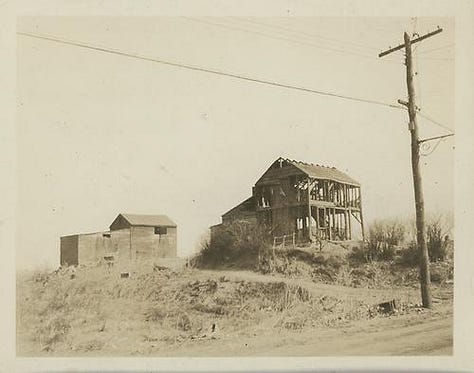

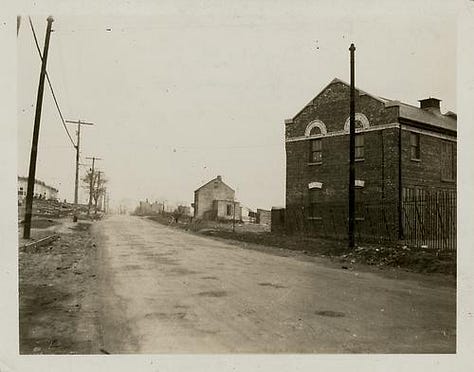

Working with then-borough president Maurice Connolly, Rothstein devised a plan to sell the land to the city for use as its first municipal airport. Knowing the land would fetch a higher price if it had buildings on it, Rothstein slapped up 48 homes, cheap, foundation-less facades propped up by little more than bargain lumber and greed.

The shoddy development, dubbed the "Phantom Village," was patrolled by watchmen "energetically assisted by a set of strong-jawed dogs"1 to discourage nosy reporters and curious would-be buyers.

Rothstein's dream of swindling the city never materialized, as he was gunned down in 1928 over an unpaid gambling debt. The following year, the city chose Floyd Bennett Field as its airport site. The Phantom Village slowly decayed back into the swamp.

Over the next decade, the land became a dumping ground for everything from Eighth Avenue subway rock to rubble from the demolished Wallabout Market, along with countless tons of unsanctioned debris.

Demonstrating his uncanny knack for identifying underutilized city land and for finding creative ways to pay for it, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses negotiated with Rothstein’s estate to acquire the land in exchange for forgiveness of back taxes. It cost the city nothing, and Moses later used its valuable peat to landscape other park projects around the state.

ALL FAITHS

With all this talk of draining the swamp, it’s only fitting that a sizable contingent of the Trump family resides in the neighborhood. A modest plot at Lutheran All Faiths Cemetery holds Donald Trump’s grandparents, his parents, and his older brother, Fred Jr. As for Donald himself, the man who turned “drain the swamp” into a political mantra, he has no plans to join them, preferring instead to be buried at the Trump National Golf Club in Bedminster, New Jersey.

Earlier this week, I spent about an hour wandering around the graveyard in the rain, fruitlessly searching for the Trump family gravesite.

The southern section is dotted with headstones and monuments bearing surnames like Hauser, Huber, and Hoff, reflecting the area's early German heritage. There are also several newer Chinese graves sprinkled throughout, marking the city's ever-shifting immigrant population.

Though I had no luck tracking down the grave—there are, after all, over half a million people buried there— it was by no means a wasted walk.

For some reason I don't know and don't want to know, after I have spent an hour or so in one of these cemeteries, looking at gravestone designs and reading inscriptions and identifying wild flowers and scaring rabbits out of the weeds and reflecting on the end that awaits me and awaits us all, my spirits lift, I become quite cheerful, and then I go for a long walk.

Joseph Mitchell

While I may not have had the same sort of epiphany as the great chronicler of New York City, Joseph Mitchell, I did find the walk through the undulating terrain of All Faiths restorative.

The damp air smelled of blooming honeysuckle, and the ground between graves was carpeted with tiny pink and white bindweed flowers. Towering clumps of flowering multiflora rose (an invasive thorny plant that can grow up to 2 feet a week, but looks beautiful when it's not your problem) swallowed trees, obelisks, and monuments whole.

As the drizzle turned to a steady rain, I finally gave up my quest.

For a far more entertaining account of a similarly unsuccessful search, read this great 2016 Esquire piece by Nell Scovell: "A Visit to Trump's Graveyard." In the piece, Scovell recounts a confrontation with Daniel Austin, Jr., the President of All Faiths Cemetery, who, upon learning she is a reporter, kicks her off the premises.

It’s a great read on its own, but the real kicker came three years later, when New York Attorney General Letitia James sued the cemetery’s leadership, including Austin Jr. and his father, for mismanagement. The lawsuit alleged that the pair, along with other members of the not-for-profit cemetery board, paid themselves exorbitant salaries, took out personal loans and mortgages for relatives, and collected retirement pay while still drawing regular paychecks—all as the cemetery slid into disrepair. As of 2024, more than $1.6 million has been returned, and the cemetery is under new management.

BOCCE

A couple of days before my walk through the graveyard, I visited Juniper Valley Park, the former swamp and dumping ground recently described as the Central Park of Queens. For a weekday morning, the park was humming with activity.

A man crouched in the dirt, harvesting bunches of mugwort and garlic mustard from the same land where the British once extracted peat. A wide expanse of green playing fields was filled with groups of children grouped by the color of their t-shirts.

There was an older gentleman holding court on the exercise equipment, whose bold decision to workout shirtless had resulted in an incandescent, hot pink sunburn. There was a pickup basketball game, a pickleball round robin, and a father pushing his baby in a stroller while dancing on rollerblades.

The most interesting thing by far, though, was the action on the park's meticulously maintained bocce courts.

A contingent of around a dozen mostly senior men gathered around one of the courts, watching, cajoling, and hurling little balls with a precision and agility that took me by surprise.

I watched a man in his seventies, with cropped white hair and a plaid shirt tucked into high-waisted pants, gingerly roll his ball down the turf, curling it around the opposing team's previous shot, before it stopped inches away from the smaller ball, or boccino, that is the game's target.

He was followed by another man in a striped tracksuit who took a more violent approach, hurling his ball into the tightly packed cluster, sending the others careening every which way, an agent of chaos in well-worn velour.

Then there was Larry, who didn't say much but commanded an obvious respect from his bocce peers. Larry, a small man with a silver brush cut and mirrored wrap-around sunglasses, embodied the ethos of his all-black "MAGA Never Surrender" t-shirt, and bowled several winning rounds when his team looked like they were down for the count.

Probably the best player, however, was the only one who looked like he didn't qualify for an AARP card. He was tall and tan, with a shaved head and a preternatural control over his rolls, which sometimes seemed to defy the laws of physics. Without fail, he always managed to land his ball closest to the boccino, eliciting groans and begrudging compliments in Italian from the assembled players and audience. The future of bocce is in good hands.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio features some barking, some chirping, some trains, and, most prominently, the sounds of the bocce court.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Born in Baden-Baden, Germany, in 1865, Eugene L. Armbruster immigrated to New York at the age of 17 and joined the H. Henkel Cigar Box Company in Brooklyn, eventually running the business alongside his brother.

After retiring, Eugene would bring his camera and a copy of the 1873 Beers Atlas of Long Island on long rambles through the city, spending most of his time in Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island. The thousands of photographs he produced are an invaluable document of a city on the verge of an epic transformation, and many of them are quite beautiful and a little bit eerie.

All the photos below were taken in Middle Village in 1923.

NOTES

Marshes and bogs have been used throughout history as ritualistic burial grounds, generally reserved for criminals, outcasts, or victims of human sacrifice. Had sleepwalker Clarence Smith never been found, he might have become a modern-day bog body, like the Tollund Man, a 2,400-year-old corpse whose body was so well preserved when peat cutters in Silkeborg, Denmark, found it, it was initially mistaken for a recent murder victim. The acidic decaying mosses act as a pickling agent, tanning and preserving the skin while leaching the calcium from bones, warping and dissolving them in the process. Who knows what bodies you will find when you drain the swamp?

St. John Cemetery, on the southeastern edge of the neighborhood, is one of nine official Catholic burial grounds in the New York metropolitan area. Among the many notable New Yorkers buried here are Maria Cuomo, John Gotti, Robert Mapplethorpe, Geraldine Ferraro, Charles Atlas, and Lucky Luciano—the infamous mob boss and one-time protégé of Arnold Rothstein.

https://www.nytimes.com/1941/06/08/archives/rothsteins-shoddy-village-will-become-a-playground-for-queens.html?unlocked_article_code=1.K08.LXQv.-H1SRVoKaFGN&smid=url-share

The juxtaposition of those homes and the mausoleums that look the same... brilliant.

Finally reading…I, too, dream of swindling the city, and would like to be referred to as “the Big Bankroll”!