Happy to be back in The Neighborhoods after my brief hiatus at the end of the year. I hope everyone is having a productive and safe start to 2025. My thoughts are especially with friends and family in Los Angeles this week.

A warm welcome and thank you to everyone who recently signed up. If you’re new here, I send out this newsletter weekly, featuring a collection of photographs and an audio recording focused on a different NYC neighborhood. I also enjoy delving into aspects of a place’s history that catch my interest. Like my photographs, my goal isn’t to provide a comprehensive or entirely accurate portrayal of a neighborhood—I simply share what piques my curiosity.

If you want to skip right to the pictures, scroll down to the Sights and Sounds section below.

For my first neighborhood of the year, I arbitrarily chose Maspeth in western Queens. Over the course of walking and photographing this past week, I kept coming across scenes and streets that I recognized from previous wanderings in the city. It turns out I have, unwittingly, spent a lot of time photographing the neighborhood.

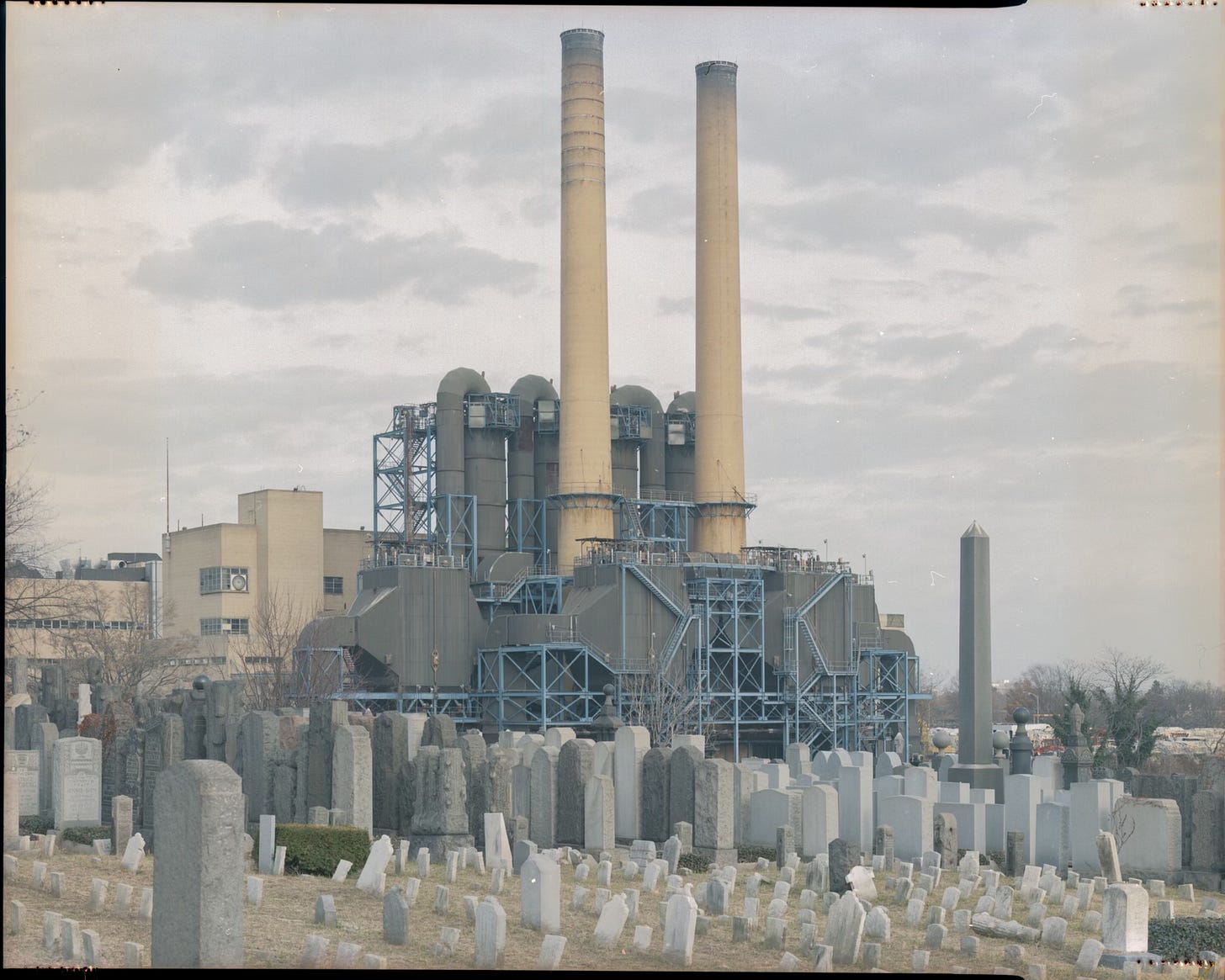

Maspeth is where I took the first image for my End of New York Project:

I’ve also made several photographs in the neighborhood’s dramatic cemeteries.

And in 2021, I photographed this location, a future microgrid battery storage site, for Bloomberg Businessweek Magazine.

It’s a neighborhood that I know well, but, until this week, I didn’t really know at all.

Maspeth is one of the oldest settlements in Queens, a two-and-a-half square-mile enclave that arose on the banks of Newtown Creek. Besides the creek, the neighborhood's borders are the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway to the north, Metropolitan Avenue to the south, and the tracks of the New York Connecting Railroad to the east.

Once a pristine estuary, the marshes and islands of Newtown Creek have gradually been graded over, infilled, and occupied by a variety of industrial operations whose years of flagrant, toxic dumping resulted in the creek's designation as a Superfund site in 2010.

A significant portion of Maspeth is still dedicated to industry, though the noxious odors of copper smelting and animal rendering have been replaced by diesel fumes from the ubiquitous Amazon and FedEx delivery vans that crowd the neighborhood's narrow streets. Everything from cheesecake to custom corrugated cardboard boxes is made in or trucked through the neighborhood's industrial corridor.

On a recent frigid dawn morning, I found myself enveloped in a cacophony of hissing air brakes, bleating backup alerts, and the incessant rumble and clatter of eighteen-wheel behemoths barreling through Maspeth's cracked and potholed streets.

Besides the industrial zone and Maspeth's residential section, a significant portion of the neighborhood is devoted to the dead, whose numbers exceed the neighborhood’s living population by a considerable amount.

Calvary Cemetery, Mount Zion Cemetery, and Mount Olivet Cemetery—once a popular weekend getaway—are all located partially or entirely in Maspeth.

THE BAD WATER PLACE

Maspeth's name, like several other city neighborhoods, is a corruption of a Native American name, Mespaechte. The Mespaechtes were a local Lenape tribe that lived off the marshes' once-abundant fish, shellfish, and wildlife. A common translation of Maspeth is "Bad Water Place," which, given the whole Superfund status thing, seems slightly too on the nose. As it turns out, pharmacist and amateur ethnologist William Wallace Tooker, the source for the original translation, changed his mind and said the name was more likely to translate something to the effect of "An Inundating Tidal River."1

The stream and its tributaries had their rise in wooded swamps, flaggy pools of water fed by flowing springs, all of which opened out into a broad expanse of low lands consisting of extensive marshes, muddy flats and peat bogs.

All those flaggy pools and flowing springs made Maspeth attractive to colonizers who would make it the first organized European settlement in what would become Queens.

In 1642, Puritan minister Francis Doughty obtained a massive tract of land (13,332 acres) from the Dutch West India Company. The deed, dated March 28, 1642, is the oldest document on file in the Land Bureau at Albany.

Doughty, who had recently been kicked out of the English colony in Taunton, Mass., for his controversial take that every infant should be entitled to a baptism, figured that the famously tolerant Dutch would let him set up shop on their turf. The Dutch, who liked the idea of having a human buffer between them and the native population whose land they were occupying, were more than happy to comply. Director-General Kieft let Doughty and twenty-eight English Quakers establish the village of Maspeth "with power to erect a church, and to exercise the Reformed Christian religion which they profess."

Just one year later, Doughty, like his neighbors Jacques Bentyn in Astoria and Anne Hutchinson in The Bronx, was driven off his land after Kieft's war against native tribes triggered a series of retaliatory raids.

Maspeth was eventually resettled and Doughty moved on to Virginia where he demonstrated "troublesome but unsuccessful witch-hunting proclivities."

THAT SICKENING STENCH

For thousands of years, the tidal flats of Newtown Creek provided an abundance of food for the Mespatches, and newspaper reports as late as 1858 documented the "wonderful and plentiful" abundance of soft-shell crabs that could be purchased for just 62 cents per dozen underneath the Maspeth bridge.

By the late 19th century, however, Newtown Creek was a fetid, stinking waterway, its greasy surface stippled with oil, animal fat, and blood. Like downriver Blissville, several large industrial concerns set up shop along the creek, and the grimy banks were lined with "villainous stench factories."

Immense bubbles of varied hues flow from the sewer’s mouth and after drifting a distance, first like miniature bombs, emitting puffs of vile gases. These combined vapors are wafted to every quarter with the changes in the wind, carrying sickness and death in turn to all parts.

Newtown Register, March 27, 1884

While several oil refineries and Peter Cooper's glue works dumped their toxic byproducts from the Brooklyn side of the creek, the Queens side was no slouch in the fouling department, with a panoply of animal rendering plants, fertilizer factories, and copper smelting facilities all contributing to the putrid miasma.

One of the most notorious facilities was the factory owned and operated by Henry Bosse of "horse-bologna sausage fame." The German-born purveyor of pickled horseflesh had developed quite a reputation for "transforming decrepit quadrupeds into odoriferous bologna sausages." While horses past their prime would typically be sold to glue and fertilizer factories for around $1.50, Bosse cornered the market, offering $4 to $10 per head.

When his neighbors found out what he was actually doing with the horses, "there was a great falling off in the demand for country sausages and bolognas."

Though Bosse’s horsemeat was a hard sell in the States, Belgians and Germans couldn't get enough of it importing over 100,000 pounds of pickled horseflesh each month.

While you may think a horse sausage impresario would want to keep a low profile, in the 1890s, Bosse's name made regular appearances in the headlines. The butcher was frequently in trouble with his creditors and was forced to move several times. His operation held the rare distinction of being the smelliest establishment on all of Newtown Creek.

In 1892, he spent some time in jail after threatening to kill his housekeeper, Helena Roll—“a large woman, not bad looking, and cannot speak good English”—who was pregnant with his child.

Two years later, he was sent to prison after ignoring the health inspector’s order to cease operations and performatively "braining" a horse in front of them.

JOE K

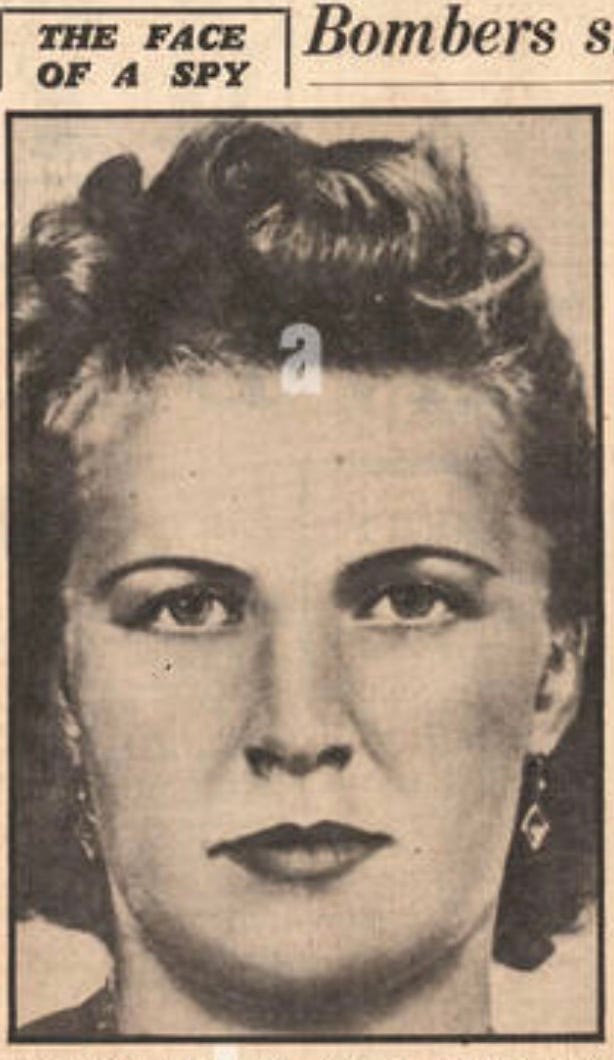

One frequent Maspeth visitor who may have appreciated Bosse's equine delicacies was Kurt Frederick Ludwig. Born in Ohio and raised in Germany, Ludwig moved back to the States to set up a spy ring in nearby Ridgewood. Ludwig recruited Lucy Boehmler, an 18-year-old Maspeth resident who had recently graduated from Grover Cleveland High School, to be his secretary.

Boehmler, who claimed she joined the spy ring because "she thought it might be fun," used her apparently considerable charms to sweet talk hitchhiking soldiers into revealing military secrets.

Ludwig would send letters with details gleaned from his surveillance of airplane manufacturing plants, ship docks, and army posts to the upper echelons of the Nazi party. Both Heinrich Himmler (code name Manuel Alonzo) and Reinhard Heydrich, the man whose capacity for evil impressed even Hitler who called him "the man with the iron heart," received Ludwig's missives.

To avoid detection, the secret information was written in invisible ink and hidden inside personal letters signed by "Joe K."

When the FBI got wise to the plot and broke up the ring, Boehmler, nicknamed "The Maspeth Mata Hari," testified against her co-conspirators. Joe K. got 20 years in prison, while Boehmler, thanks to her cooperation, received just five. Had this happened in actual wartime, the whole crew would most likely have been executed.

Ludwig was quite the troublemaker in prison and was sent to solitary confinement for causing “great dissension” and for refusing to keep his toilet clean.

THE STOMPING MARE

Speaking of Nazis, in 1964, Hermine Braunsteiner, who had worked as a guard at two different concentration camps, was living at 52-11 72nd Street in Maspeth.

Braunsteiner, who earned her nickname after she stomped a prisoner to death with her jackboots, had been tracked down to her Maspeth address by famed Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal.

She became the first Nazi war criminal to be extradited from the United States.

LUDAR

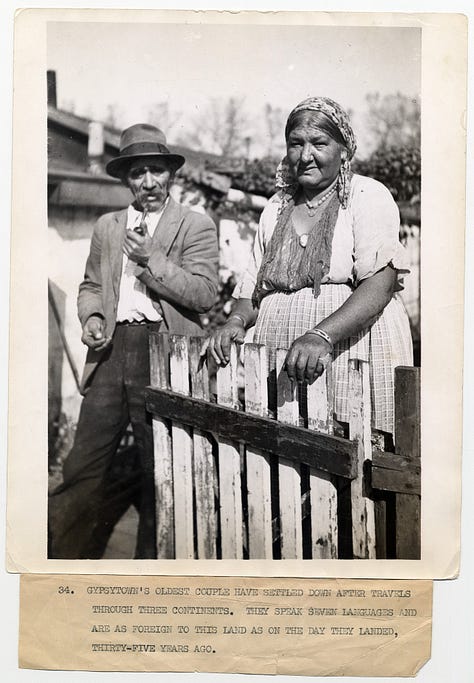

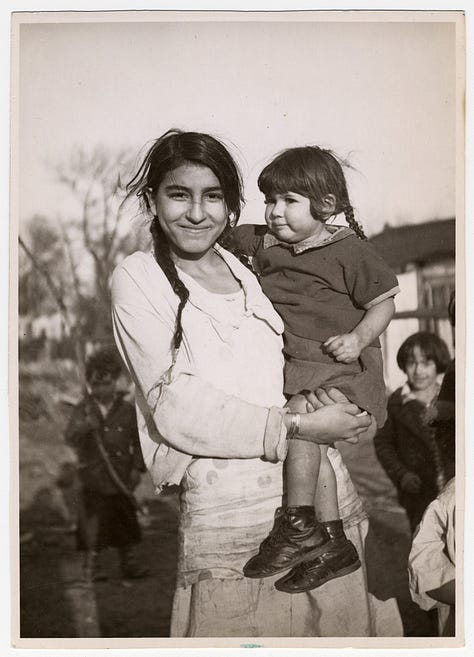

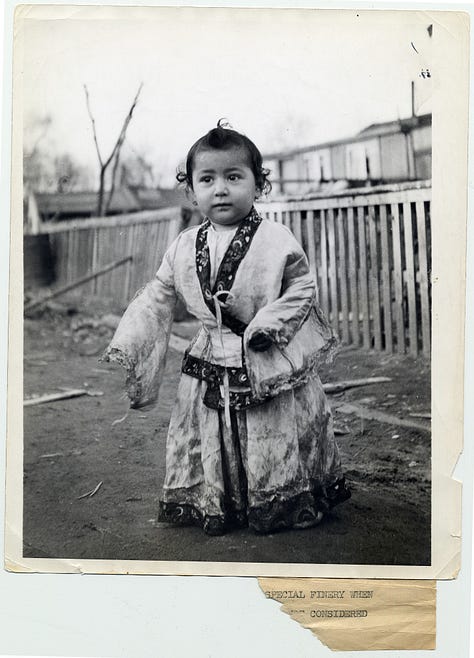

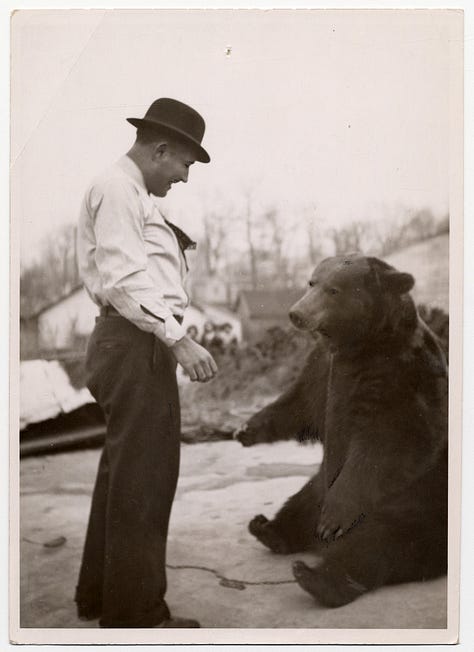

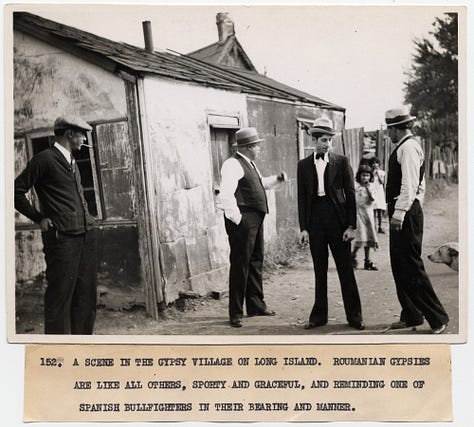

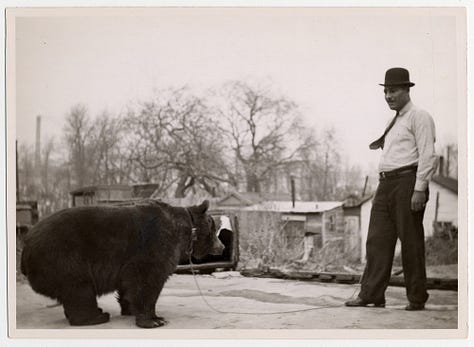

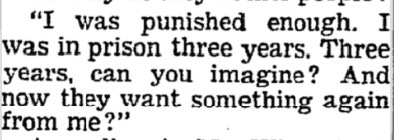

Beginning in 1880, large numbers of Ludar or "Romanian Gypsies," immigrated to the United States from primarily northwestern Bosnia. They were skilled animal trainers and passenger manifests indicate that bears and monkeys were in included among their possessions.2 Many of them settled in western Maspeth on the outskirts of Mt Zion cemetery.

From about 1922 to 1939, a sprawling assemblage of over 100 ramshackle buildings, tents, and bear pens near Maurice and Borden Avenues was home to over 45 Ludar families.

In the summer, the encampment’s population would dwindle as they fanned out to popular vacation destinations like the Jersey Shore or the Poconos to tell fortunes or put on carnival shows. At the end of the season they would return to Maspeth where many of the men worked as coppersmiths.

In my writeup on Blissville, I linked to Matt Linhart’s fantastic documentary on the neighborhood. The documentary, which also includes Linhart’s interview with a former Ludar encampment resident, is well worth watching.

In 1938, the department of housing and buildings determined that the tents and shacks of the encampment were “unfit for habitation and should be razed.”

A few years later, a significantly larger swath of the neighborhood was razed during the construction of Robert Moses’ Long Island Expressway.

The LIE, which was partially built to deal with the problem Moses had caused by barring truck traffic from his state parkway system, cut straight through the heart of the neighborhood. Within weeks of its opening, commuters were referring to it as the “world's longest parking lot.”

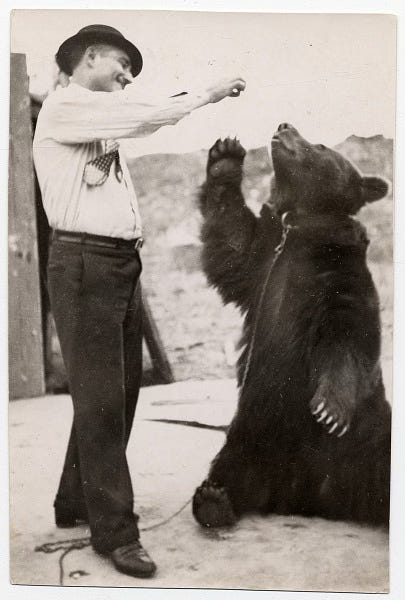

THE MET OVAL

The Metropolitan Oval is possibly the oldest continuously used soccer field in the country and certainly the one with the best view. The field was built by German and Hungarian immigrants in 1925. Since many of the German-Hungarian players worked in the local knitting mills, they named their team “the Knitters.”

For the first 75 years of its existence, there was nary a blade of grass to be found in the Oval earning it the nickname, the Dust Bowl.

The caretaker in the 60s and 70s would use an old Ford to drag a metal mattress box spring across the field to get rid of the rocks before watering it by hand with a garden hose to keep the dust down. If a player wasn’t cut to ribbons by the rocks, the goals had jagged metal fencing for netting and there was a steel pipe fence ringing the field just yards from the touch line that could really ruin their day.3

Despite the lack of greenery, or maybe because of it, the Met Oval became known as New York’s soccer mecca. Future stars like Werner Roth played for the German-Hungarian Sports Club before becoming captain of the New York Cosmos. Several European clubs chose the field for exhibitions on their U.S. Tours.

Over time, as the demographics of the surrounding neighborhoods changed, new teams like Los Millionarios and Diablos Rojos began to lease the field for their games, a development that wasn’t always viewed positively by long term residents.

Eventually, to deal with an ever increasing tax burden, the Met’s shareholders created the not-for-profit Metropolitan Oval Foundation. In 2007, Metropolitan Oval was one of the first clubs in the nation to be chosen as a United States Soccer Federation (USSF) Development Academy and continues to be the premier soccer pitch in the city.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

I think I finally have my audio setup back and running. This week features the hum of Flushing Ave traffic, a school playground at recess and the concrete plants and lapping waters of the Newtown Creek.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

The photographs from the Ludar encampment I posted above were taken by Carlos de Wendler-Funaro (1893–1985), an anthropologist and collector known for his extensive work documenting the lives of Romani people in the United States. Wendler-Funaro was born in Brooklyn and attended Erasmus Hall High School in Flatbush. His extensive documentation of the Ludars of Maspeth can be attributed to his role as personal secretary to Steve Kaslov, better known as the “King of the Gypsies".

You can see Wendler-Funaro’s entire archive on the Smithsonian website.

NOTES

In 2013, the EU was rocked by a horsemeat scandal when several grocery store offerings purporting to contain 100% beef were tainted with, or even wholly replaced by, horsemeat. The Guardian put together a “horsemeat scandal essential guide” if you have the stomach for it.

If all this horsemeat talk has you considering switching to a vegan diet and you are a fan of pan pipes, have I got the place for you. To the best of my knowledge, Andean Garden is the city’s only vegan Peruvian restaurant. Actually, I am not entirely clear if it is a restaurant or just a ghost kitchen. It’s only open on weekends, and the address is the 3rd floor of a residential building in Maspeth. I am going to try and visit this weekend and will report back.

When researching the horse sausage king, Henry Bosse, I came across a contemporary of his, with the same name, whose exploits were much more pleasant to read about. Henry Peter Bosse started work as a draftsman in the U.S. Corps of Engineers in 1874. By 1887 he was chief draftsman. During his tenure he made hundreds of photographs of Upper Mississippi River that he printed as cyanotypes.

In 2002, Twin Palms published a book of the work (now out of print) called Mississippi Blue.

https://www.newspapers.com/article/brooklyn-eagle-tooker-maspeth-name/162318113/

https://www.smithsonianeducation.org/migrations/gyp/lud.html

https://metropolitanoval.org/about/

I'm actually new to your newsletter, just wanted to say what an amazing job you've done. Every neighborhood feels like a chapter of a novel I can't wait to read the next one.

"Besides the industrial zone and Maspeth's residential section, a significant portion of the neighborhood is devoted to the dead, whose numbers exceed the neighborhood’s living population by a considerable amount."

What an observation and an positively odd way of putting it!