I spent an hour this week upgrading the map of New York City neighborhoods I have been using to chart my progress on this project. Thankfully, I had finally run out of the fluorescent green and orange magnets that I had been previously using, so I took the opportunity to make a fresh start. I read that yellow was both Albert Einstein’s and Jeffrey Dahmer’s favorite color, so that made my choice easy.

During my re-magnetization project, I noticed a glaringly blank space in the heart of Brooklyn. Part of that is by design. Since I first moved to New York, I have always been drawn to the edges, those places that feel the least urban. However, as this project has evolved, I have grown to love exploring and documenting the city's more historic and developed centers, where the accretions of history are often visible.

In the magnet-less heart of my map sits Flatbush, the geographical center of Brooklyn. Years ago, when working on a project in Far Rockaway, I always noticed one particular stretch of businesses along Flatbush Avenue during my commute. Unlike other parts of the city where the old buildings have either been meticulously restored and maintained or replaced by large modern blocks with glass storefronts, this section of Flatbush’s commercial strip has remained largely unchanged.

The three-story buildings lining the street that used to draw shoppers from all over the city were still intact. What initially caught my eye were the alterations to the facades. Awnings that extended upward as well as out. Massive two-story panels that reduced the buildings to two dimensions save for a bit of weathered cornice peeking out.

A look at municipal tax photos from the 1940s reveals that this aggressive signage is by no means a modern phenomenon. While the businesses may have changed—Sultana Silk Stockings and Adam Hats (America’s ‘One Price Hatter’) have been replaced by Jimmy Jazz and Raga Muffin—the advertising approach hasn’t. Of course, some of the more extreme interventions may have something to do with the fact that it is cheaper to cover a facade than restore it, but that doesn’t change the fact that these buildings’ primary function is still to attract customers.

In many ways, this sort of urban palimpsest makes the perpetual and rapid reinventions of the city easier to wrap your head around. Unlike neighborhoods such as Gowanus or Long Island City, where the swift and extreme transformations can engender a kind of cognitive dissonance, Flatbush’s progression—from Lenape to Dutch to Jewish to West Indian—is tangible, written in the streets and buildings of the neighborhood.

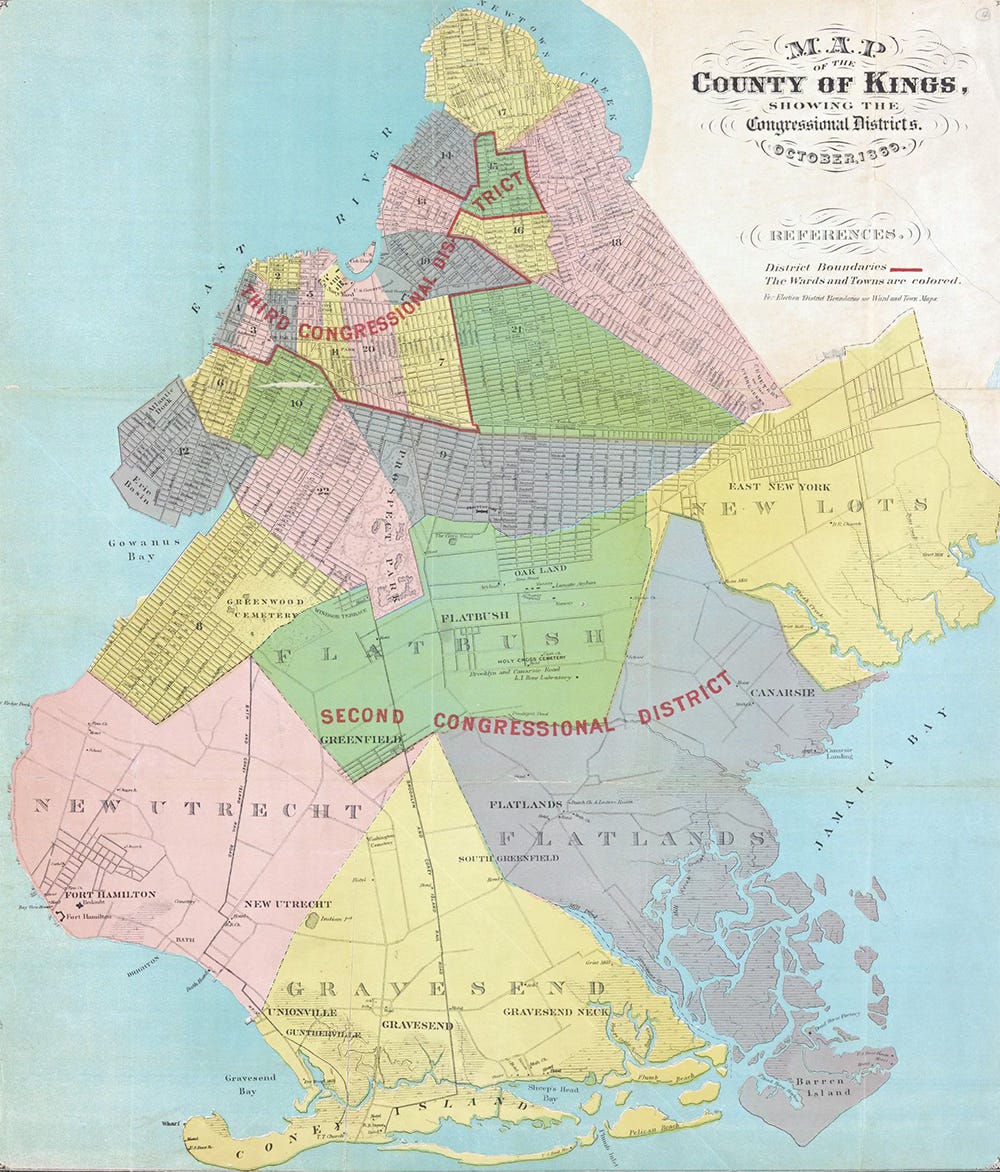

The Shrinking of Flatbush

Flatbush was one of Brooklyn's original six towns, encompassing a vast swath of the borough, including Windsor Terrace, Kensington, Pigtown, Midwood, and Crown Heights.

Over the years, the surrounding neighborhoods have gradually chipped away at Flatbush’s edges. Now, the neighborhood is a compact rectangle centered around the Flatbush Reformed Dutch Church, located at the intersection of Church and Flatbush Avenues, the heart of the original village.

The smaller enclaves Flatbush has spawned, like Ditmas Park and Prospect Park South, have established themselves enough to qualify as bona fide neighborhoods in their own right. While Google Maps claims that Flatbush runs from Rogers Ave to Coney Island Ave, for my purposes (and to continue milking this project for as long as humanly possible), I decided to split the neighborhood in two.

I’ll save the area west of Ocean Avenue, sometimes called Victorian Flatbush, for another day.

Vlacke Bos

Flatbush is an Anglicization of the Dutch Vlacke Bos, meaning “wooded plain.” Another name for the area was Midwout or “middle woods.” It seems that had it been left up to the Dutch, every neighborhood in Brooklyn would have a name corresponding to the density of its woodlands.

Flatbush Ave, the diagonal spine of Brooklyn, was built on an old Native American footpath. The busy thoroughfare traverses its namesake neighborhood on the 10-mile trip from the Manhattan Bridge to Jamaica Bay. At the intersection of Flatbush and Church Avenues, the commercial and historical heart of the neighborhood stands the 230 year old Flatbush Reformed Dutch Church, completed in 1662. The church's land has been in continuous use for religious purposes longer than any other in New York City.

The current incarnation of the church was completed in 1793.

Buried behind (and underneath) the church are the members of several prominent Brooklyn families with familiar names like Ditmas, Gerritsen, Livingston, Lefferts, Martense, Van Siclen, and Vanderveer.

Most, if not all, of those families were slaveholders. A census taken in 1738 found that nearly one-third, 120 of Flatbush’s 539 inhabitants, were enslaved people.1

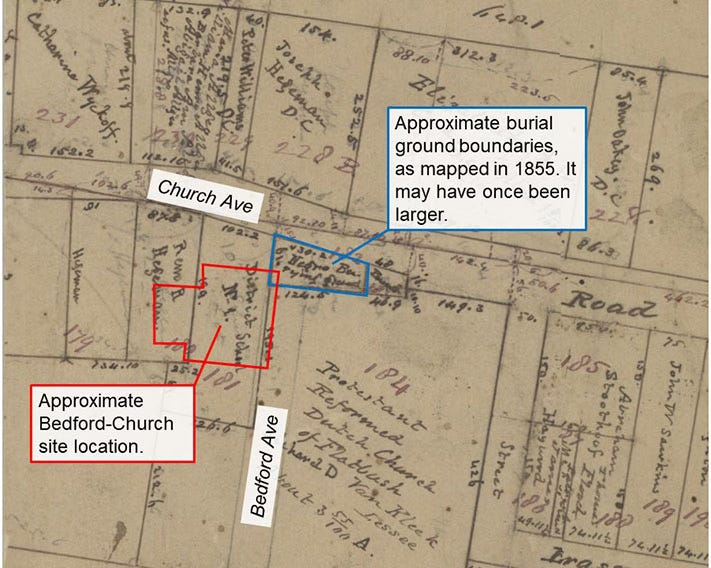

With a few exceptions, none of the enslaved were buried in the church graveyard but were instead interred a block away in the vicinity of 2286 Church Avenue. While human remains have been discovered on this site during various construction projects over the years, the actual location of the Flatbush African Burial Ground was not known until 2020, when a map from 1855 was discovered in The Center for Brooklyn History’s archives.

In 2020, locals rejected a plan proposed by the de Blasio administration to build affordable housing on the site. Instead, the Parks Department said it would create a memorial. The project, which was supposed to be completed by October of this year, has not begun.

Behind the burial site is the Erasmus Hall High School, one of the oldest secondary schools in the United States. Founded in 1786 as the Erasmus Hall Academy, the school’s alumni run the gamut of New York characters, from the revered—Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond—to the reviled—Arthur Sackler. Other notable Erasmus graduates include Bobby Fischer, Bernard Malamud, Nora Talmadge (of Bayside fame), Clive Davis, and Marky Ramone.

Everybody Who’s Anybody Is Moving To Babylon.

Flatbush followed the familiar urban progression from rural to residential with the advent of new transportation options. The neighborhood’s population surged after World War I when the children of Jewish immigrants took advantage of the new subway lines and traded their tenements for the new construction and open spaces of southern Brooklyn. ”They dressed fashionably when they worshiped in new brick synagogues, built within sight of the slim white spires of a Dutch Reformed church.”2

Flatbush quickly became one of Brooklyn’s more desirable neighborhoods, with shopping hotspots like the Art Deco Sears Roebuck store,

and movie palaces like the opulent (and recently restored) Lowe’s Kings Theater.

Eventually, though, the same pattern that initially populated the neighborhood repeated itself, and the children of the children who had moved to Flatbush to escape Manhattan chose to escape the city entirely.

Flatbush resident Patty Hassett, interviewed by the NYTimes in 1968 couldn’t wait to get out of Flatbush: 3

“Flatbush was good for our parents, but I want to move to Babylon. That’s the place to be these days. That’s the place with status. Everybody who’s anybody is moving to Babylon.”

Out of curiosity, I googled the name Patty Hassett. Though I have no way of knowing if it is the same woman, I did find a Patricia Hassett who, from 1993-1998, served as the Vice President for Finance and Administration at Flatbush’s own Brooklyn College. Not this time, Babylon.

Another Flatbush teenager who was sick of the neighborhood was cartoonist and national treasure, Roz Chast:4

“I’m living in this four-room apartment in Brooklyn, a crummy part of Brooklyn—not a dangerous part of Brooklyn, just a crummy part of Brooklyn—and I just did not understand why I was there.”

While the changes of the seventies were marked by turmoil in other parts of the city, Flatbush fared better because of community organizations like the Flatbush Development Corporation. The FDC, which was formed in 1975, organized tenants and shop owners to improve housing conditions and created job training and after-school and summer youth programs.

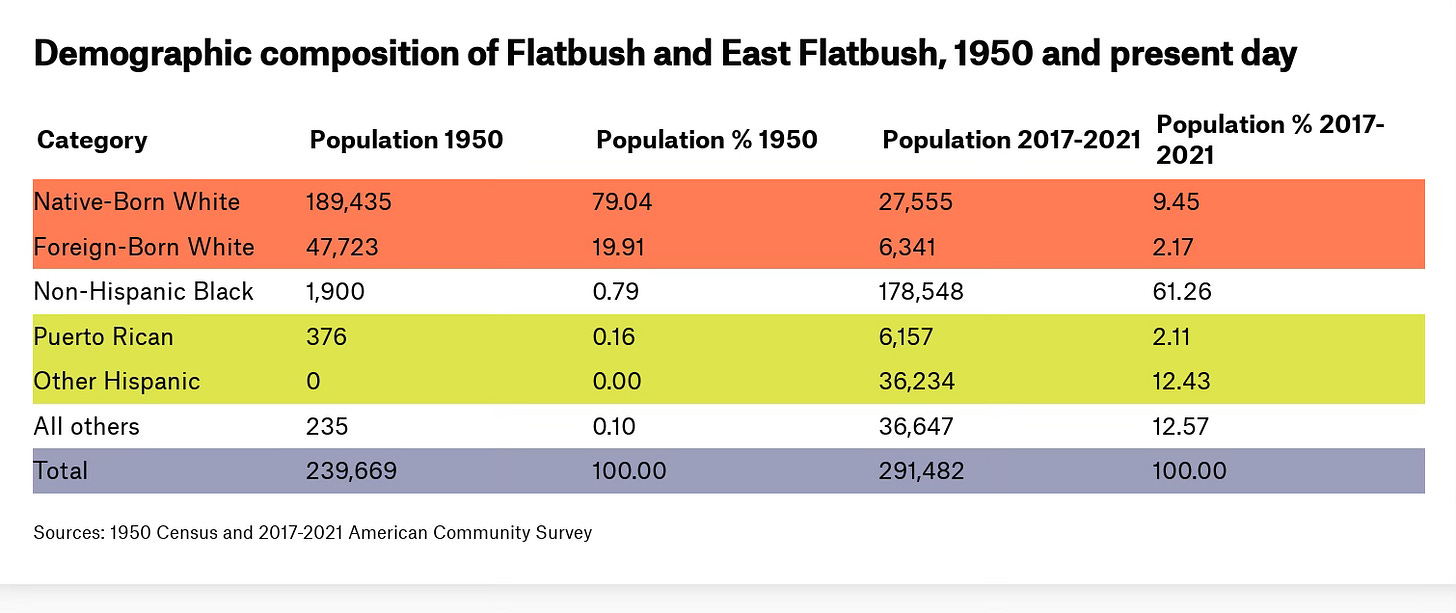

An excellent piece on Flatbush’s evolution by John Mollenkopf in Vital City charts the neighborhood’s transformation from a middle-class Jewish neighborhood to a middle-class West Indian neighborhood.

Over the course of a few decades, the Jewish delicatessens were replaced by jerk chicken joints and Korean-owned groceries.

Family Red Apple boycott

What transpired at one of those groceries, the Family Red Apple, kicked off an eighteen-month boycott of Korean-owned grocery stores throughout the city.

On January 18, 1990, less than a month into Mayor Dinkins’ first term, Giselaine Fetissainte, a 46 year old Haitian American woman, entered the Flatbush Avenue grocery store to do some shopping. According to Fetissainte, the line was too long, so she put down her shopping basket and left. When the manager asked her to show him the contents of her bag, she refused. He grabbed her by the neck and slapped her repeatedly, causing her to fall to the floor. She was taken to the hospital by ambulance and treated for injuries.

The manager, on the other hand, claimed that Mrs. Fetissainte had refused to pay the full amount for her goods and alleged that she threw peppers at the cashier, spat on her, and disrupted the register displays. They said that when Mr. Jang placed his hands on her shoulders to restrain her and request that she leave the store, she fell to the floor and began screaming.

These days, of course, there would be security camera footage and several cell phone videos of the incident to confirm what happened. But regardless of what happened in the store, outside the store, demonstrations began. Protest leaders carrying signs and brandishing bullhorns massed outside the market chanting ''Don't buy! Don't buy! Don't buy!''

Dinkins’ leadership on the issue was seen as ineffectual by both sides. Similar protests of Korean-owned groceries took place in other neighborhoods. After 16 months, the owner of Family Red Apple sold the store.

In 2018, in an uncanny example of history repeating itself, a video of employees of a Chinese-owned nail salon in Flatbush, Happy Red Apple, attacking one of their customers went viral. The customer had refused to pay for a botched eyebrow job, and two employees went crazy with some broomsticks.

Just like 28 years earlier, protestors surrounded the store for several weeks. In 2020, the charges against the salon employees were dropped. Today, the former nail salon is home to the Eats Delicious restaurant and bakery.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording starts on a quiet Sunday morning on Flatbush Ave. On my walk, I passed La Piscine De Bethesda, where a Sunday morning service had just started. I listened for a bit before continuing my walk. The last section, fittingly, was recorded on Church Avenue, where the bells from Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church had just started to toll. This was right around the time my microphones died, so the end of the recording is a little muddy, but I think it is still interesting.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

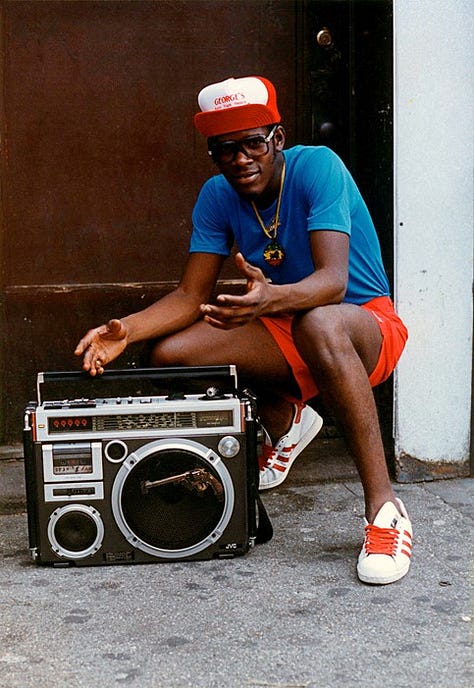

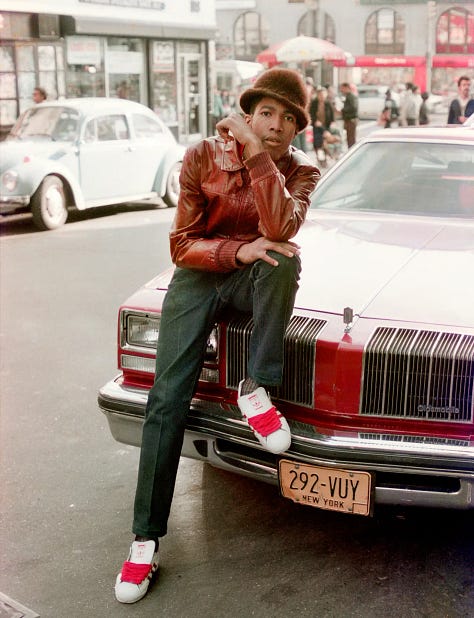

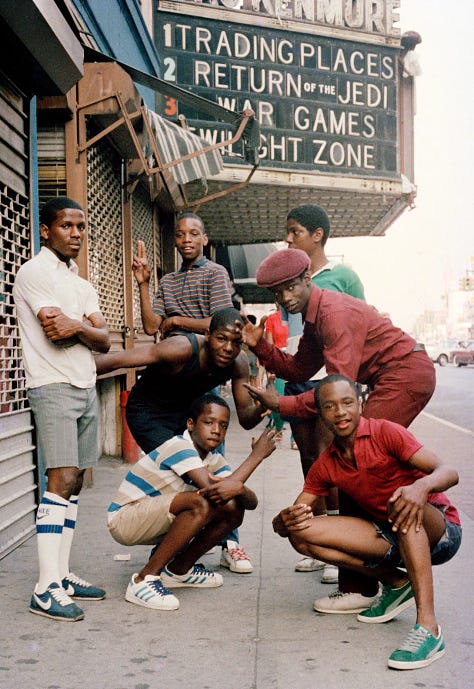

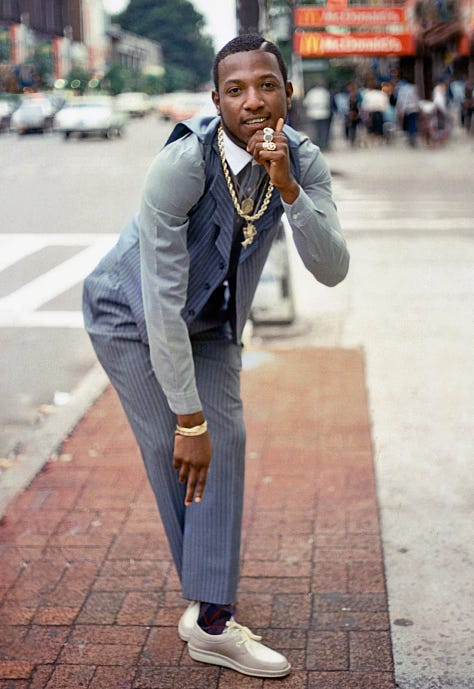

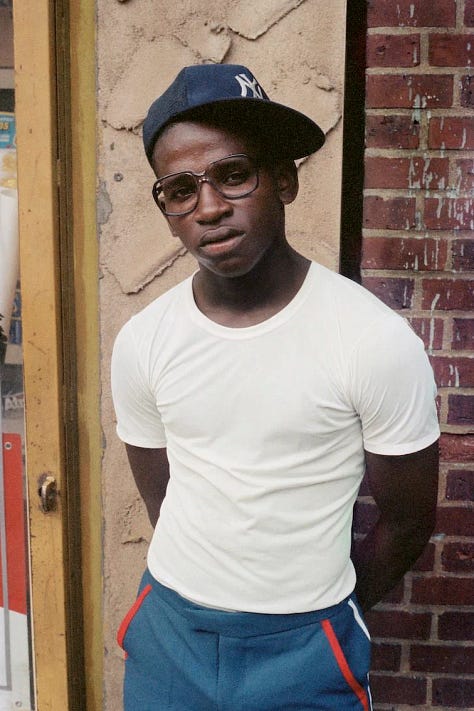

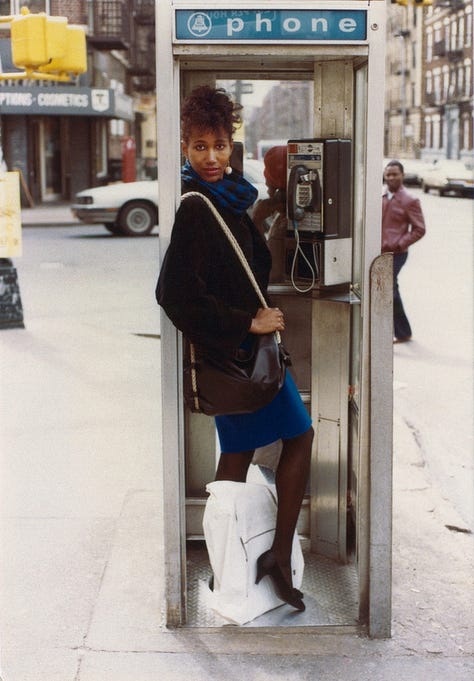

Jamel Shabazz needs no introduction. The Brooklyn born photographer has been called ”the foremost photographic chronicler of New York hip-hop culture in the 1980s," by the New York Times and “New York’s Most Vital Street Photographer” by Aperture Magazine.

Shabazz grew up in Red Hook before moving to East Flatbush with his family in the 1970s. Here is a good piece that talks about the influence of Leonard Freed (another Flatbush resident) on his work and the racism he and his family experienced when they first moved to Flatbush.

His work is in the collection of The Whitney Museum, The Studio Museum in Harlem, The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, The Fashion Institute of Technology, The Art Institute of Chicago and the Getty Museum. He has published several books of his work including Back in the Days, A Time Before Crack and Seconds Of My Life.

All these photos are from Flatbush/East Flatbush. To see more of Shabazz’s photos, you can visit his website.

ODDS AND END

For a really in-depth, well-researched look at Flatbush’s history, be sure to check out Jennifer Boudinot’s website named, appropriately enough, Flatbush History.

Lords Of Flatbush is a 1974 comedy directed by Stephen F. Verona, who would later go on to direct Angela Lansbury's Positive Moves video (5⭐). Set in 1958, the story follows four lower middle-class Brooklyn teenagers known as The Lords of Flatbush. The leather jacket wearing Lords “chase girls, steal cars, shoot pool, get into street fights, and hang out at a local malt shop.” It features early performances from Sylvester Stallone and Henry Winkler, who referenced Stallone’s character when creating his Fonze character in Happy Days. Aaayyy.

The trailer features one of the absolute worst theme songs I have ever heard.

Erasmus High isn’t the only institute of higher learning with an impressive list of alumni. Brooklyn College, the first public coed liberal arts college in the city, which straddles the Midwood/Flatbush border, counts Bernie Sanders, Shirley Chisholm, Mel Brooks, David Geffen, Barbara Boxer and Frank McCourt among its graduates.

Ebinger’s Bakery, a New York institution founded in 1898, invented Brooklyn Blackout Cake. The iconic cake got its name from the mandatory blackout drills at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during WWII. Ebinger's went bankrupt in 1972, devastating legions of fans who pined for the three layers of devil's food cake separated by a dark chocolate pudding, covered in chocolate frosting, and sprinkled with chocolate cake crumbs. For a survey of modern options, check out Caitlin Van Dusen’s deep dive for City Lore.

Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York City: Oxford University Press, 1998), 128

After Era of Stability, Flatbush Yields to Change; The Talk of Flatbush “The New York Times: Wednesday February 14, 1968”

Gopnik, Adam. “Scenes from the Life of Roz Chast.” The New Yorker, 9 Dec. 2019, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/30/scenes-from-the-life-of-roz-chast. Accessed 17 Oct. 2024.

Thanks! Shabazz is so good! I briefly contemplated walking through that door. I may have to go back.

Wow. You are NOT kidding about that Lords of Flatbush theme song. Bad writing, mediocre singing, and a VERY uninspired melody. Oof. That said I sorta want to see the movie now.