I’ve previously brought up my reluctance to write about Manhattan’s “blue chip” neighborhoods, those places that people who don’t live in the city know by name. Not only have their stories been told ad nauseam, but they often lack that uncanny quality that I find so intriguing about further flung, lesser-known neighborhoods. Chelsea’s quaint streets, lined with brick townhouses, trendy restaurants, and art galleries, are about as quintessential a New York backdrop as it gets. Still, dig deeper into its history, and you start to uncover some of the weird.

Getting Griddy

In 1750, farmer Jacob Somerindyck sold the land between today’s 21st and 24th Streets, from the Hudson River and Eighth Avenue, to British Major Thomas Clarke, who named his new estate “Chelsea” after London's Royal Chelsea Hospital for veterans.

Eventually, the estate became the property of Clarke’s grandson, Clement Clarke Moore, who is most famous for penning A Visit From St. Nicholas, better known as The Night Before Christmas. The story, "arguably the best-known verses ever written by an American,”1 is primarily responsible for our modern conceptions of Santa, whose depiction was inspired, according to Clarke, by a “portly, rubicund Dutchman who lived in the neighborhood.”

The Commissioner's Plan of 1811 has been called "the single most important document in New York City's development” or, less generously, by Edith Wharton, “hide-bound in its deadly uniformity of mean ugliness.” The initiative mandated that a gridiron street pattern be superimposed on the hitherto undeveloped land of Manhattan.

The plan made the subdivision of Clarke’s estate an inevitability. In 1818, Clarke anonymously penned "A Plain Statement, addressed to the Proprietors of Real Estate, in the City and County of New York.

The great principle which governs these plans is, to reduce the surface of the earth as nearly as possible to dead level. ... The natural inequities of the ground are destroyed, and the existing water courses disregarded. ... These are men who would have cut down the seven hills of Rome. We live under a tyranny with respects to the rights of property

Eventually, Clarke realized the grid could make him rich and embraced the new ordinances, dividing and selling his land parcel by parcel, amassing a small fortune in the process.

DEATH AVENUE

In the 1840s, Staten Island’s favorite son, Cornelius Vanderbilt, built tracks for his Hudson River Railroad right down the middle of the newly built 10th and 11th Aves. The trains shared the streets with a frenetic scrum of horses, carriages, pedestrians, and eventually cars and trucks, a combustible situation that soon earned both 10th and 11th Avenue the nickname Death Ave.

There were so many accidents and fatalities that the railroad hired actual cowboys from western cattle ranches who rode in front of the trains waving red flags or lanterns to alert jaywalkers.

You would think the cacophony of a large steam locomotive would be enough to catch anyone’s attention, but unfortunately, for little Seth Low Hascamp, neither the noise nor the West Side Cowboys proved an effective deterrent, and during a game of follow the leader, he fell between the wheels of a freight train and was “ground to death." The ensuing public outcry, including a march of 500 of Seth’s schoolmates, “many of them being no bigger than the flags they carried,” led to the eventual elevation of the tracks and the creation of the High Line, now one of the city’s top attractions.

OREO

Besides the High Line, one of Chelsea’s biggest draws is its eponymous market and food hall occupying a whole city block. Before it was a food hall, the building was the headquarters for Nabisco, which I only just learned is an abbreviation of National Biscuit Company. The building holds a special place in the hearts of cookie enthusiasts as it was here that the world's best-selling cookie, the Oreo, was “invented” in 1912.

Though many people think of them as cheap knockoffs, Hydrox cookies were first on the scene, invented in 1908, four years before the virtually indistinguishable Oreo. While the name Hydrox sounds like it would be great for getting out tough stains, it was inspired by the hydrogen and oxygen elements within the water molecule. The name is supposed to connotate “purity and goodness,” something the Nabisco execs probably chuckled about all the way to the bank.

Recently, Leaf Brands, the current manufacturer of Hydrox, sued Mondelez, the current manufacturer of Oreos, seeking $800 million in damages because of "lost sales and reputation.” Leaf accused Mondelez employees of stashing Hydrox packages behind other cookies and placing them on higher, less accessible shelves. Perhaps the Hydrox obfuscation was not a nefarious Oreo plot but rather the work of activists who weren’t happy with the cookie maker’s offer to build a border wall out of their confections.

In 2017, Hydrox removed all artificial ingredients and obtained non-GMO certification, and Oreo came out with a special limited edition Swedish fish-filled cookie.

ORE

Speaking of toxic goods and things you may want to keep hidden, the former Baker & Williams Warehouse, at 513-519 West 20th Street, was once used by the Manhattan Project to store nearly 220,000 pounds of uranium that had been secretly shipped into the nearby Hudson River docks. The ore was then distributed to various government facilities involved in developing the atomic bomb.

In the early 1990s, the government remediated the site, and workers removed over a dozen drums of radioactive waste still being stored in warehouses. Today, the high-end Jack Shainman Gallery occupies the ground floor.

SHUNK

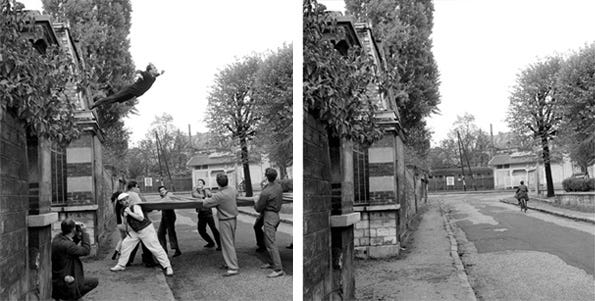

I spent a year working on the Harry Shunk archive, one door down from the former Baker & Williams Warehouse, blissfully unaware of its history as a uranium storage facility. It was a strange year that had me pouring over endless stacks of silver gelatin prints in a caged, windowless storage unit while my coworkers binge-listened to Harry Potter audiobooks. Shunk (with his partner János Kender) documented some of the most prominent conceputal New Realist artists from the 50s-70s, including Christo, Yayoi Kusama, and, most famously, Yves Klein. Leap into the Void is by far Shunk’s most well-known image, though nobody knows it as a Harry Shunk photograph but rather a Klein artwork.

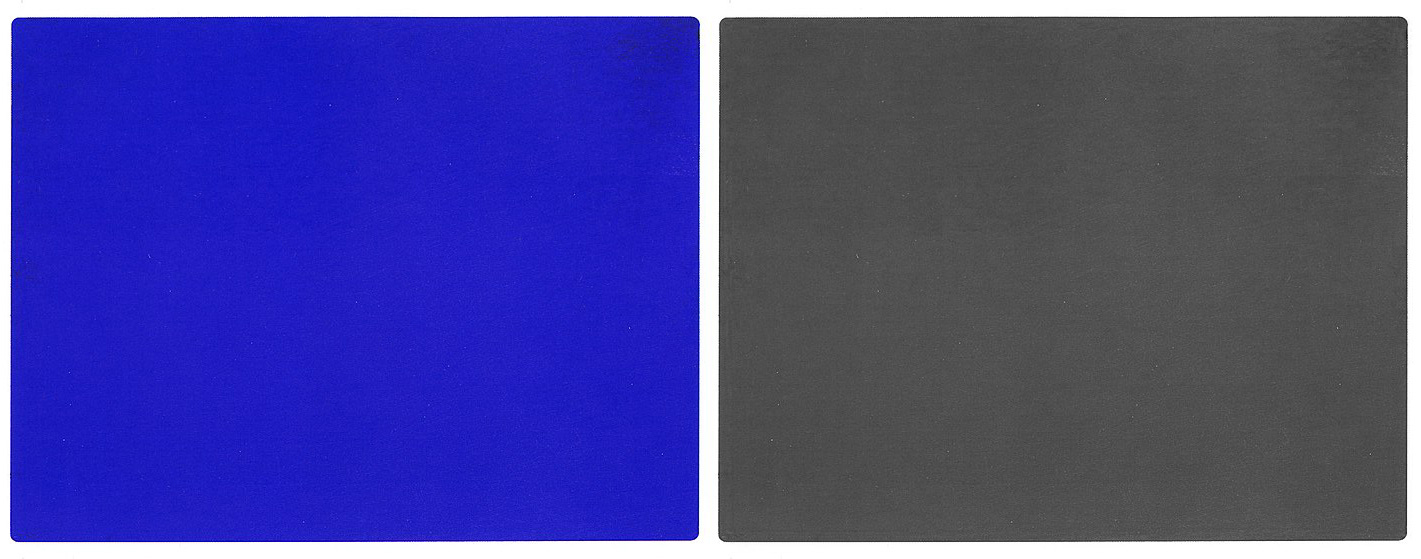

I always found it interesting that Shunk worked exclusively in black and white. From Christo and Jean-Claude’s 250,000 square foot saffron, Valley Curtain, to Yves Klein's signature blue, color played a pivotal role in the artwork he was documenting. Maybe Shunk, whose role as documentarian sometimes bled into that of collaborator, was co-opting some of the conceptual framings of his fellow artists, making a subtle commentary on the crass commercialization of the art world by stripping the work of its color. Or maybe he only had access to a black-and-white darkroom.

TIME-LAPSE

Emerging from the confines of cold storage, I soon found work as a freelance archivist at the David Zwirner Gallery, which brings me to the reason for covering Chelsea this week. This summer, T Magazine commissioned me to photograph the High Line and other buildings in Chelsea for an article, How Chelsea Became the Unlikely Center of the Art World, detailing the area’s transformation from a neighborhood of “ body shops, scrap yards, sex workers and leather bars” into the center of the art world and, eventually, a “monument to real estate developers.”

Part of the commission involved making a time-lapse of the line at the David Zwirner Gallery during its blockbuster Kusama show. The 30-second time-lapse was distilled from over four thousand images made during an all-day shoot, lasting from 5:30 AM to 8 PM, on one of the hottest days of the summer.

Shout out to my two visitors who spelled me for bathroom breaks and brought me provisions. Also, to the guy who, upon realizing he had a captive audience, shared his theory about a government conspiracy involving buildings constructed in triplicate and how the telepathic communication abilities of dogs were the only things saving us from a space war. He cited the fact that everyone has size 10 1/2 feet as proof for these claims. Since that is indeed my shoe size, I could not refute his assertions. Satisfied, he soon moved on.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording starts at the water’s edge of Chelsea piers, takes a trip to Chelsea Market, and walks the line at the Kusama show before finally finishing off at the driving range.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

This week’s featured photographer is one of my photo heroes, Joel Sternfeld. Like many people, my first introduction to Joel’s work was his seminal project American Prospects, the result of several years spent crisscrossing the country in a VW camper with his 8x10 view camera. His photographs from the project, often funny, sometimes strange, and always beautiful, perfectly capture the changing landscape and people of the US in the 80s.

Later books include Stranger Passing, On This Site, and Walking the High Line, a book documenting the abandoned tracks of the High Line in the years before their reconceptualization as an urban park.

The High Line is a fantastic park, a true asset to the city, and an impressive achievement in urban planning. This period that Joel captured, though, was truly remarkable. His atmospheric photographs of the suspended, abandoned pathway, weaving through the cityscape, free from today’s selfie-crazed throngs, are an eerie testament to the inevitability and adaptability of nature and, perhaps, a glimpse of the future.

Visit Joel’s website to see more of his work.

all pictures © Joel Sternfeld

NOTES

It took ten days for anyone to figure out Harry Shunk had died in his Westbeth apartment, “upside down and trapped by stacks of his accumulated possessions, with only his ankles and his feet visible.”2 The apartment was so packed with stuff that they had to remove the door from its hinges to get in.

Oreos were not vegetarian or kosher until 1997, when the lard was removed from the recipe.

In 2020, Google searches for Hydrox cookies surged after President Trump touted his regular usage of hydroxychloroquine.3

If you’ve ever wandered around Chelsea, you may have noticed these small vertical stone totems distributed on 22nd St., between 10th and 11th Avenue. The project is a continuation of Joseph Beuys’ 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks), which began in 1982 in Kassel, Germany. DIA helped Beuys plant 7,000 trees throughout the city. Each tree has a stone column to keep it company.

In 1988, DIA continued Beuys’ project on 22nd Street. There are now 38 trees and their stone friends in Chelsea.

I didn’t even get to cover one of Chelsea’s most iconic landmarks, The Chelsea Hotel. This recent documentary, executive produced by Martin Scorsese, looks good: Dreaming Walls: Inside the Chelsea Hotel.

When I first moved to the city nearly 20 years ago, a friend introduced me to Village Yogurt, tucked between a GNC and a McDonald’s on 6th Ave. While it wasn’t in the Village and didn’t serve yogurt, it did have the best lunch in the city. The back wall was covered in signed 8x10 headshots. I could not identify a single person in any of the pictures.

A few years ago, they remodeled and changed the name to Green Symphony. The headshots and classical music soundtrack are gone, but the lucite-encased rice and bean tables remain, as does the #6 Combination Fantasy, a perfectly balanced plate of thin-skinned veggie dumplings, brown rice, and steamed vegetables slathered in a trio of proprietary sauces - hot, black vinegar, and tahini. It’s my favorite meal in the city.

Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. pp. 462–63

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/12/nyregion/after-a-recluses-death-a-cleanup-man-reaps-a-trove-of-art.html

https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-makes-a-cookie-great-again-11589900809?mod=e2tw

This article is amazing as always I can really tell your daughter is your inspiration

Death Ave - that's amazing. That photo with the cowboy in front of the train almost looks unreal. Wonderful photos and essay as always.