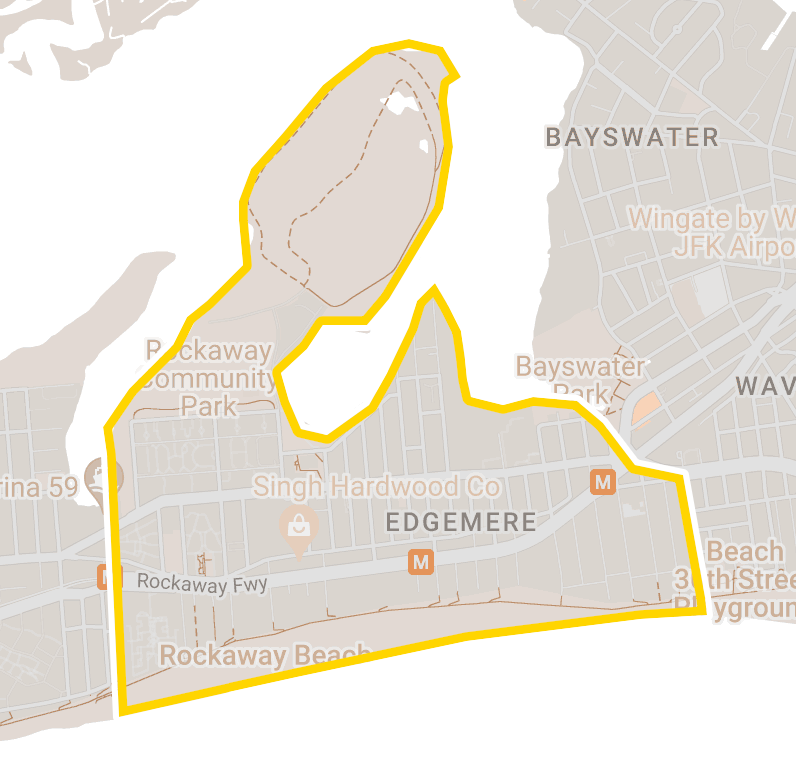

This week’s newsletter is my first dispatch from the Rockaways, the long peninsula of sand at the city’s southern edge where I’ve been photographing for almost twenty years. From the first time I came to this corner of Queens, following Flatbush Avenue to its end, over the Marine Parkway bridge, and down into Fort Tilden, I was hooked. When revisiting my old Rockaway work for this newsletter, I realized that so much of it was shot in the Edgemere neighborhood, though, at the time, I had no idea what it was called.

NEW VENICE

The original inhabitants of Rockaway, the Canarsie tribe, sold it to English Captain John Palmer for a cool £30 in 1685. Just two years later, Palmer sold the land to Richard Cornell, whose descendant, Ezra, went on to found Cornell University.

In 1892, developer Frederick J. Lancaster bought land running from Beach 32nd Street to Beach 56th Street, between the Atlantic Ocean and Jamaica Bay.

Lancaster ambitiously dubbed the area New Venice. He soon realized that his rebranding wasn’t going to catch on and changed the name to Edgemere, old English for “edge of the sea.”

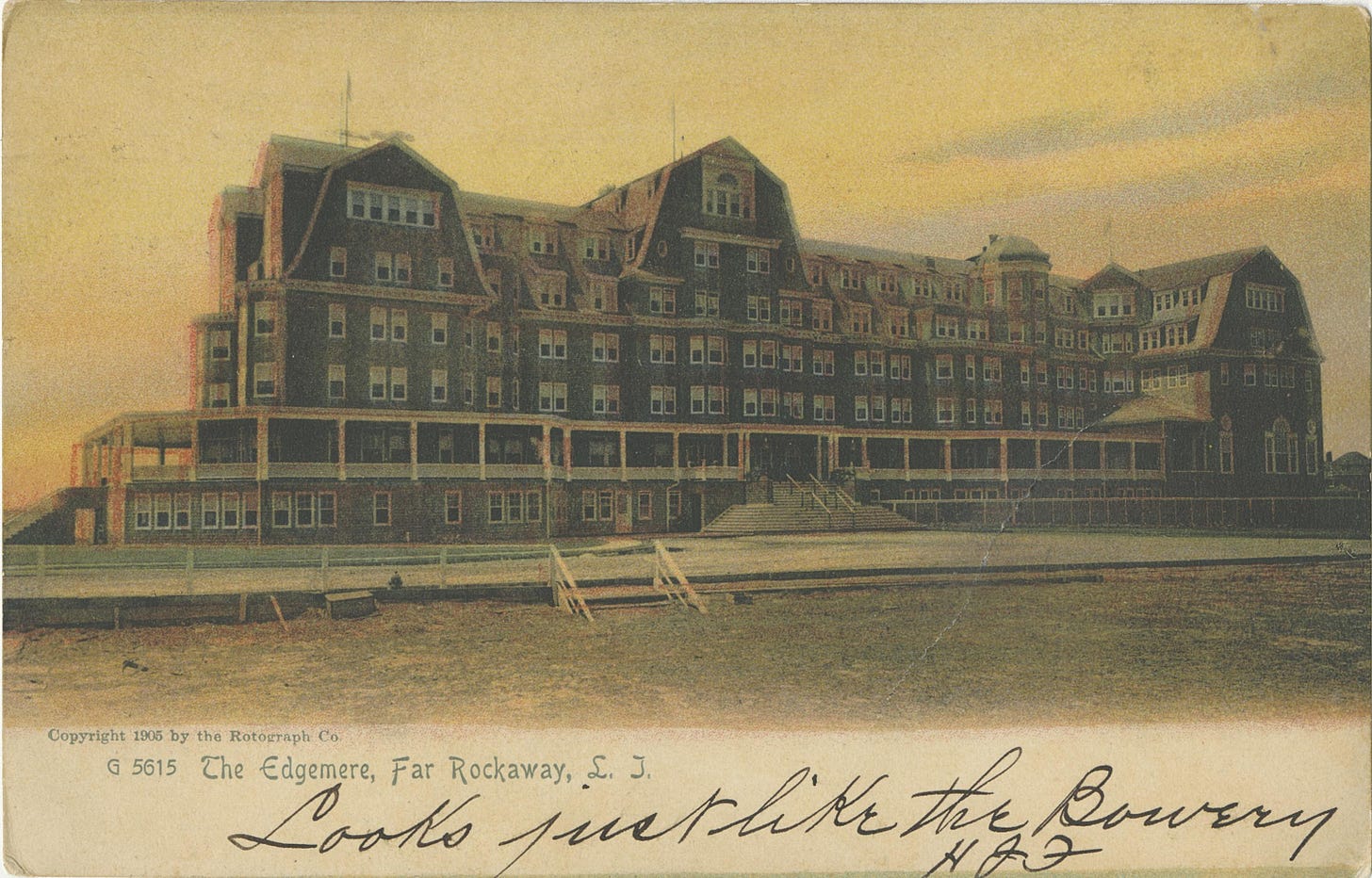

Ever since the cholera outbreak of 1833, the Rockaways had been a popular escape from the city's heat (and bacteria). The introduction of a ferry route in 1864, followed by rail service in 1869, further cemented Rockaway’s status as a summer destination. At the height of its popularity, Edgemere boasted over 60 hotels.

DR. DOOM AND HOG ISLAND

In 1996, geology professor and self-described forensic hurricanologist Nicholas K. Coch led his students on a field trip to study the effects of erosion in Edgemere. Research on some of the items they found while digging on the shore - crockery, old bricks, broken toys, led them to conclude that they were artifacts from Hog Island, a long-forgotten barrier island that had once existed off the coast of Edgemere.

In 1870, Hog Island, sitting 1,000 feet off of Edgemere’s shore, was one mile long, several hundred feet wide, and packed full of summer amusements. Particularly popular with the power brokers of the Tammany Hall machine, the island’s bathing houses, saloons, and restaurants attracted throngs of city sun worshippers to its beach.

Then, in an instant, the island was gone.1

During a great storm in the fall of 1893, the outer beach disappeared beneath the waves and every vestige of it and of all the buildings upon it was totally destroyed. Where one day had appeared this excellent pleasure resort of many thousands of people, which thousands of dollars had been invested upon, next day nothing was to be seen except an unbroken surface of water.

Professor Coch, profiled in the 1997 NY Times story, The Little Island that Couldn’t2, had spent years arguing that New York City was uniquely vulnerable to a big hurricane. He claimed Hog Island’s wholesale disappearance was a harbinger of things to come. His colleagues dismissively referred to him as Dr. Doom. Unfortunately, the damage wrought by superstorm Sandy in 2012 proved him right. Professor Coch thinks Sandy (technically not even a hurricane) was just a warm-up, and the city needs to prepare for the impacts of another, far larger storm.

“After Sandy, somebody asked me, ‘Do people still call you Dr. Doom?'“ Coch says. His reply: “No, but they’re calling me quite often now.”3

A SINGLE GREAT DESOLATION

The reason the damage from Sandy wasn’t even more catastrophic can be attributed, in part, to the failures of city planner Robert Moses’ urban renewal programs. By the 1940s, with the advent of more affordable cars and air conditioning, Rockaway had lost some of its luster, though it continued to be a popular spot for the city’s working class, who vacationed there in the summer months.

Robert Moses, however, wasn’t a fan.

“Such beaches as the Rockaways and those on Long Island and Coney Island lend themselves to summer exploitation, to honky-tonk catchpenny amusement resorts, shacks built without reference to health, sanitation, safety and decent living,”

Moses implemented his “Rockaway Development Plan,” which at its core was a program to relocate New York’s poorest residents to the furthest reaches of the city. Public housing developments went up all over the peninsula, including the Edgmere houses on Jamaica Bay. In the 1960s, over 4,000 houses and bungalows were razed in Edgemere and neighboring Averne to make room for more construction. In January 1973, the Nixon administration announced a moratorium on all federal housing subsidies for low and middle-income housing.4 The land has remained vacant ever since.

Roughly two waterfront miles of mostly barren blocks and de-mapped streets merging with the emptiness of the ocean to form a single great desolation. It is The World Without Us, a testing ground for urban entropy5

Moses’ land clearing efforts foreshadowed the city’s current “managed retreat” approach to dealing with flood-prone areas. In the program, the city offers buyouts to property owners in the flood zone and then destroys the buildings, ceding the land back to Mother Nature. Moses’ unfinished efforts created a natural buffer, an inadvertent bluebelt, like the one I wrote about in Midland Beach, Staten Island.

The eastern coast of Edgmere, reminiscent of the Solow lot in Murray Hill, remains vacant and today is a popular dumping spot, home to wild dogs and piles of unwanted car parts. The gradually disappearing striations of potholed and sandy streets, punctuated by the occasional solitary fire hydrant, are the only links to Edgemere’s bustling past.

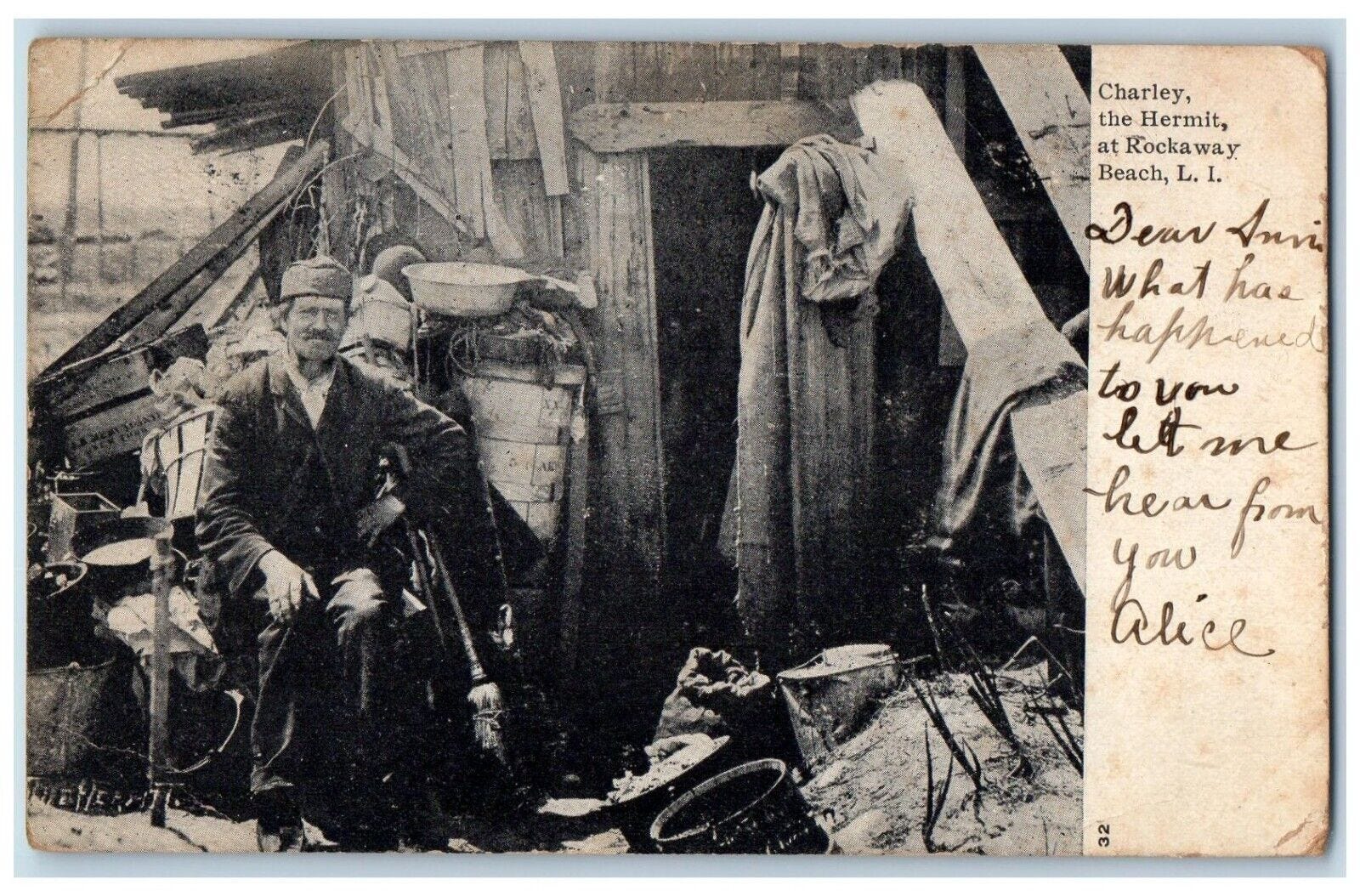

CHARLIE THE HERMIT

Long before Robert Moses was orchestrating his bulldozing campaigns, Edgemere local, Charlie the Hermit, had his home taken away from him. By 1912, Charlie had already lived on the land between Edgemere and Averne for 31 years. One day some local residents, realizing Charlie had been squatting on their property, knocked down his lean-to and kicked him off their land. This act of vigilante NIMBYism left Charlie homeless and distraught.

Charlie had come to the Rockaways from Germany, where he was known as Karl Enties and where he learned the trade of cabinet making. He told his new American friends he was saving money to bring his girlfriend over. After two years, he had finally earned enough to afford to pay for her ticket and sent the money to his brother in Germany. Then everything went downhill.

Suffice it to say Charlie would not forgive them. Upon hearing the news, he immediately went to Jamaica Bay, threw his toolbox into the water, and began collecting scraps to assemble his shack. While it may have been better to hold on to his tools before embarking on a new home-building project, the news that he had paid for his brother’s wedding to his girlfriend didn’t have Charlie thinking rationally.

Charlie survived by clamming, fishing, and “accepting tips from visitors who never failed to pay a visit to his shack when they were in the neighborhood.” I thought the idea of a hermit soliciting visitors and tips to be a little paradoxical. Upon further research, however, I found there is a long tradition of hermits interacting with other people and working jobs to sustain their off-the-grid lifestyle. That would also explain his willingness to pose for this postcard I found listed for sale by eBay seller eternal_loot:

A pretty fantastic picture of Charley (sic) and his shack. But what really drew me in was the writing on the front:

Dear Anni, what has happened to you? Let me hear from you Alice.

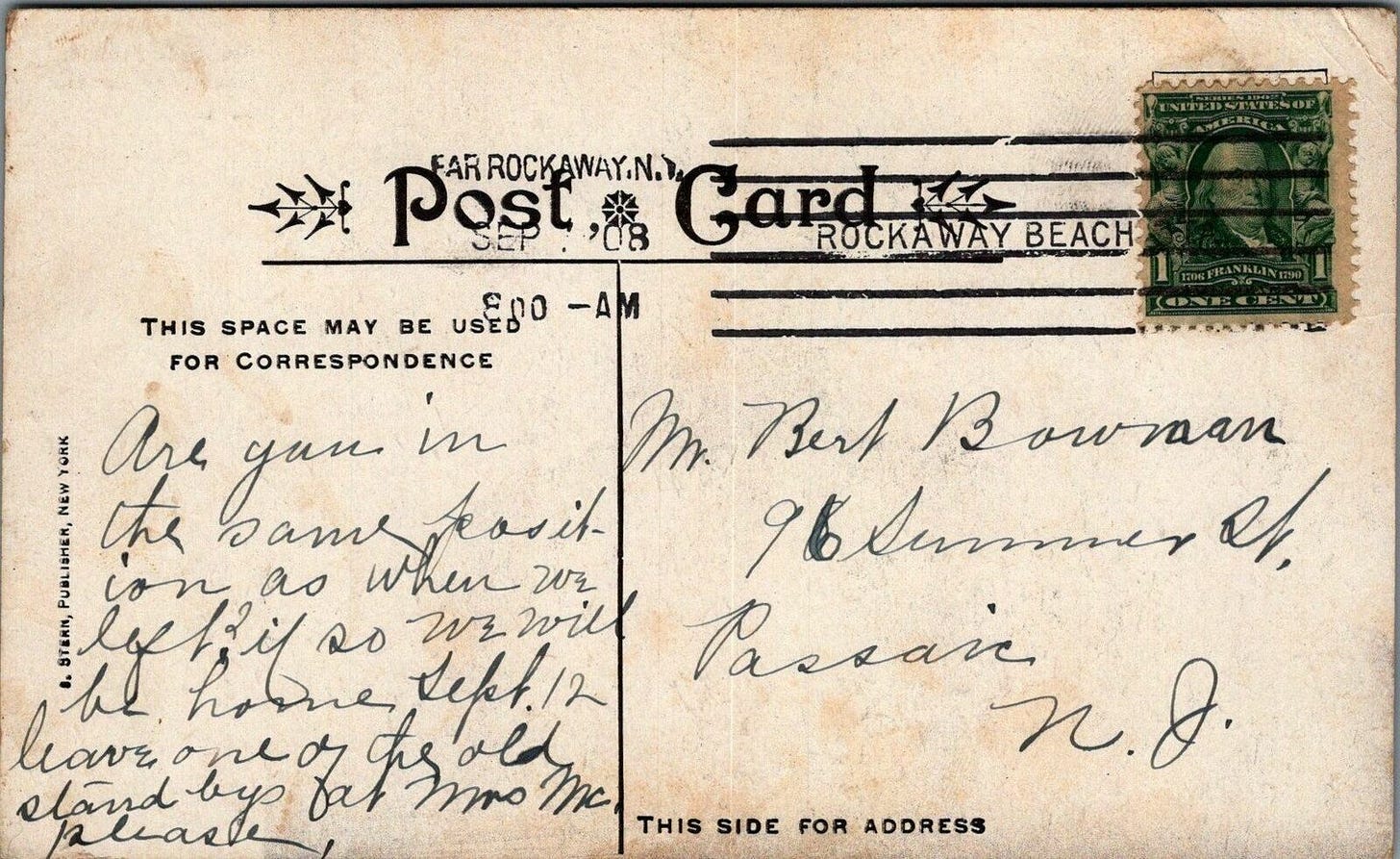

Quite a mysterious message and an interesting choice of postcard to boot. And why write on the front? Sensing my love of vintage Rockaways postcards, the eBay algorithm suggested I might like this one as well:

Correct!

And the writing on this one:

Asa says tell you he is anxious to float that boat, guess he will be glad to see you again. H.E. Clark

Woah, Asa, get a hold of yourself! And write your own postcard maybe? This is some titillating stuff for 1907. There is more on the reverse.

Are you in the same position as when we left? If so we will be home Sept. 12. Leave one of the old stand bys for Mrs. Mc please.

What position? What are the old standbys? I don’t know what I’m reading, but I want to hear more.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s sounds consist of crashing waves and some gulls. Pretty relaxing really.

FEATURED PHOTOS

This week’s photo is another from Percy Loomis Sperr, New York Public Library’s official photographer, who wins the best business card award:

New York City, all five boroughs: Street Scenes, Skyscrapers, Old Houses, Foreign Quarters, Pushcarts, Farms, Old New York Scenes. A growing collection of over 30,000 views of: 1. New York Harbor: Ships, old and modern; Skylines, Dock Scenes, Harbor Craft, Sunsets, Bridges, Naval Vessels.

Here is his picture of PS 106, the only building that was spared the wrecking ball in the 1960s. You can see the school on the bottom edge of that bird’s eye view picture above.

NOTES

For you New Yorker subscribers, this article, The Mystery of Hog Island by David Garczynski, who rode out Sandy in nearby Atlantic Beach, is worth your time.

Further recommended reading on hermits: Michael Finkel's “The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit, This true story is about Christopher Knight’s 27 years of solitude in the Maine woods. Unlike Charlie, Knight really did his best to avoid people, his one human interaction in 27 years occurred sometime in the 90s when he ran into a hiker in the woods and said, “Hi.” Now that is what I call a hermit

Since this is ostensibly a newsletter about photography (and hermits?), I should mention Alec Soth’s haunting project Broken Manual, that “investigates the places in which people retreat to escape civilization. Soth photographs monks, survivalists, hermits and runaways, but this isn’t a conventional documentary book on life ‘off the grid.’ The authors have created an underground instruction manual for those looking to escape their lives.”

“The History of the Rockaways,” Alfred Bellot

https://www.nytimes.com/1997/03/18/nyregion/queens-spit-tried-to-be-a-resort-but-sank-in-a-hurricane.html

https://grist.org/cities/nyc-hurricane-expert-sandy-wasnt-the-big-one/

https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/22/answers-about-rockaway-queens-part-3/

https://nymag.com/realestate/neighborhoods/2010/65358/

Great stuff! I visited Edgmere last November, only my second ever trip to the Rockaways. Once I was out there, I knew I had to go back. I've done three more long walks in the Rockaways since then. I was originally influenced to make the shlep by this old photography blog:

https://kensinger.blogspot.com/2010/10/north-edgemere-shore.html

I’ve long been curious about Edgemear and Far Rockaway but concerned my imagination might be better than the reality. Is it worth the trip?