According to a 2013 New York City Department of City Planning report, Corona is the most heavily Latin American immigrant community in Queens. During a recent visit, in the midst of a brutal heatwave that had seemingly every fire hydrant in the city open to the streets, the only language I heard was Spanish.

Only a few older businesses remain, like the Lemon Ice King of Corona and Leo’s Latticini, vestiges from the neighborhood’s time as a predominantly Italian American community. Like everywhere in the city, this corner of Queens is in a constant state of reinvention.

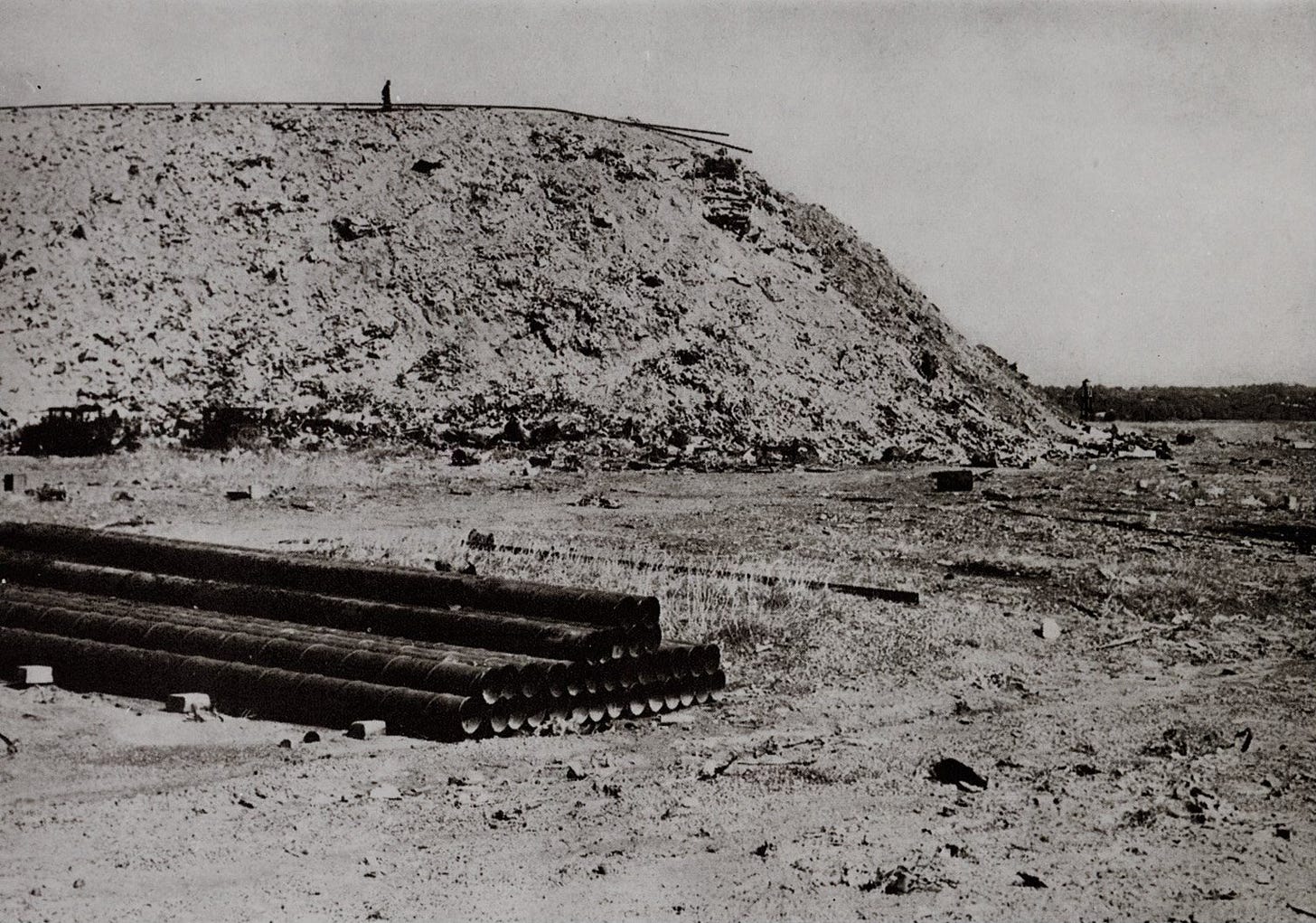

Less than a hundred years ago, F. Scott Fitzgerald described the plot of land just east of Corona as the “valley of ashes” in The Great Gatsby:

This is a valley of ashes — a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of men who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air. Occasionally a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak, and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.

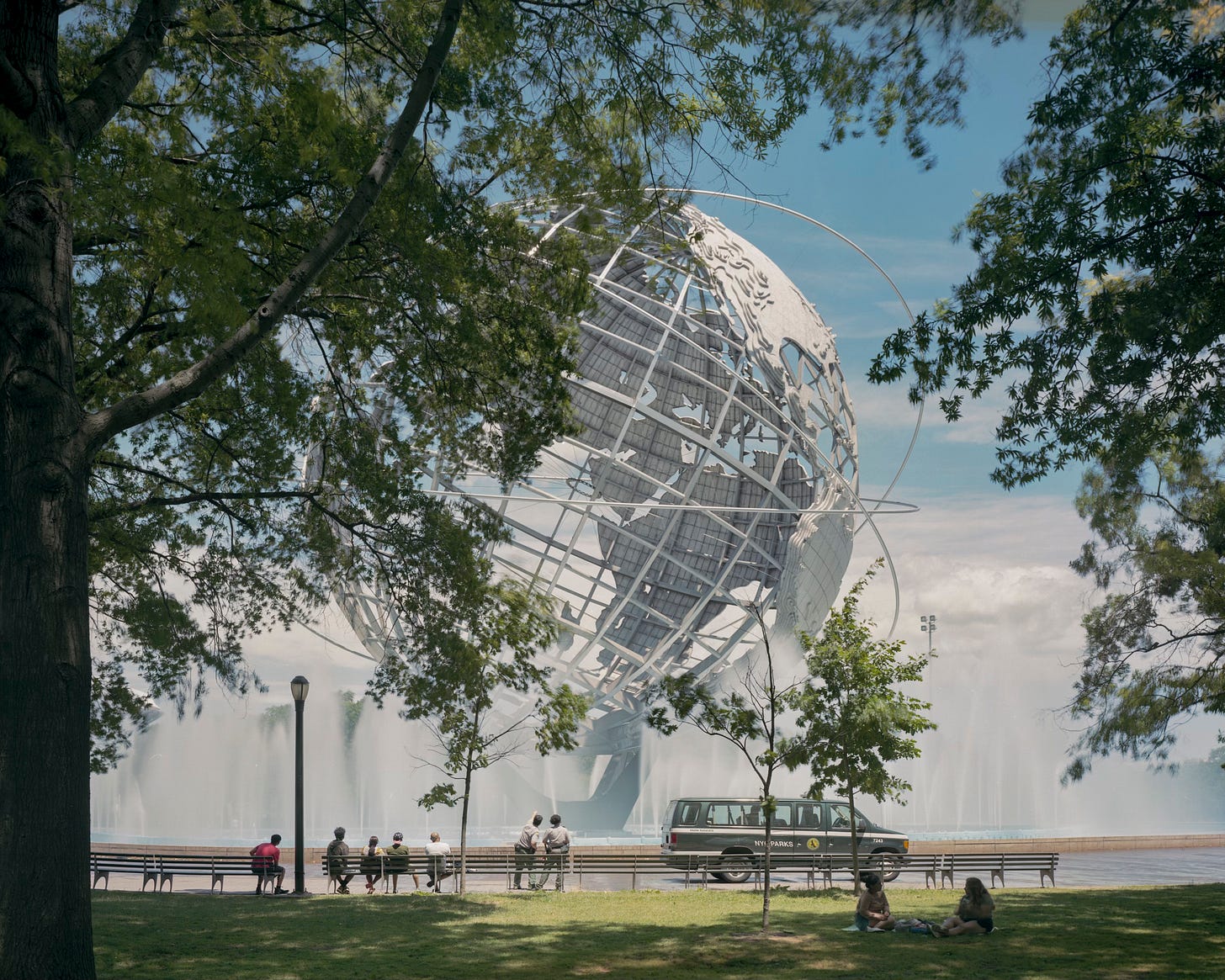

At the turn of the century, the coal-fired burners used in practically all the buildings of the city produced tons and tons of ash, and the once pristine marshes between Flushing and Corona were deemed the perfect place to leave them. In 1934, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia put an end to the privately owned dumping ground, and mounds of cinders were moved, bulldozed, and buried. Arising out of the ashes came the site for the 1939-40 World’s Fair and Queens’ largest park, Flushing Meadows.

The park (which I will dedicate a separate newsletter to) sits on the eastern border of Corona. The Long Island Expressway to the south, Northern Boulevard to the north and Junction Boulevard to the west make up the neighborhood’s other borders.

ALL STARS

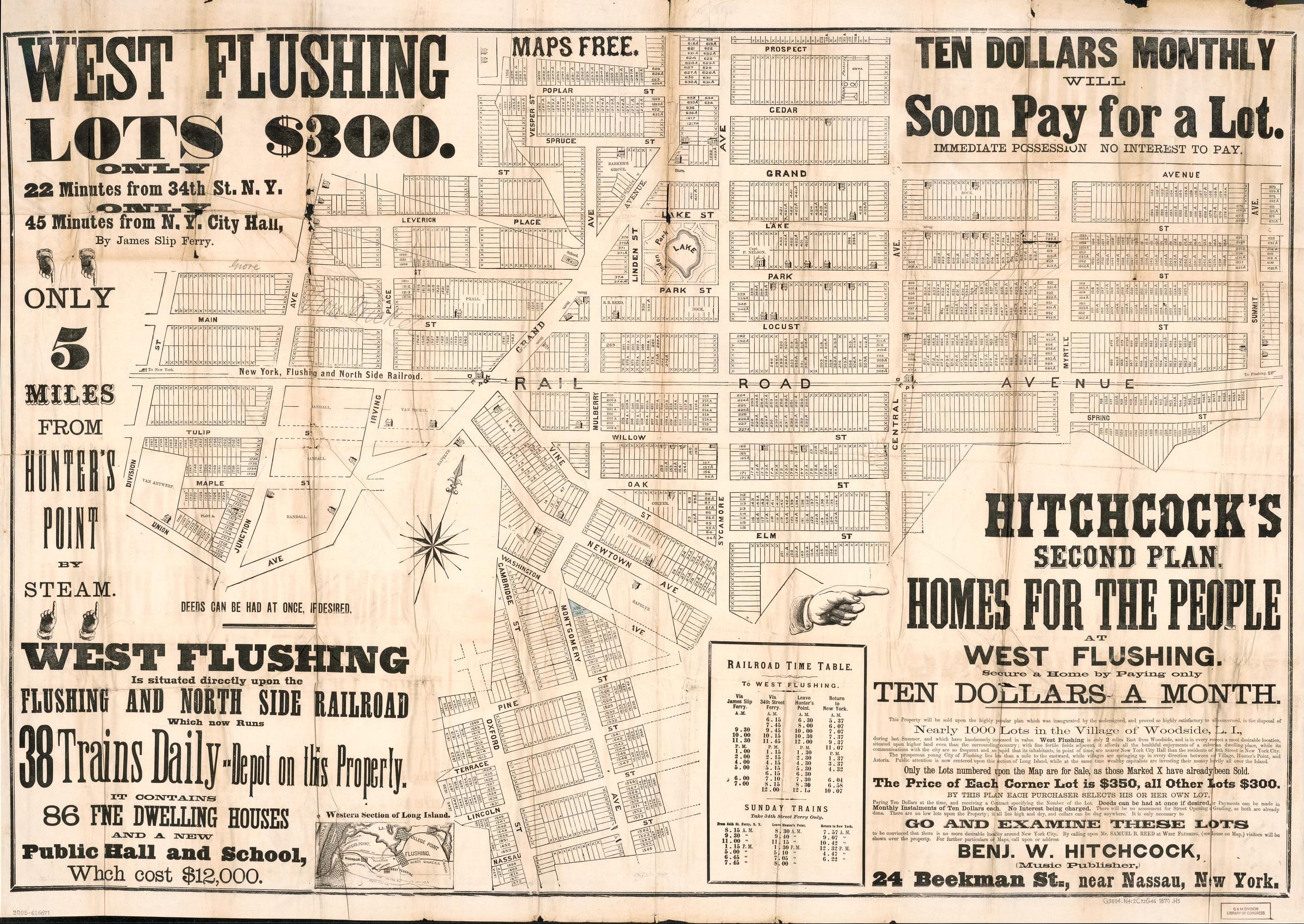

Corona began its transformation from rural community to the densely settled neighborhood it is today with the arrival of the Long Island Rail Road in 1854. Back then, the area was called West Flushing, and it was best known as the location of the National Race Course, a popular spot to catch an afternoon of harness racing.

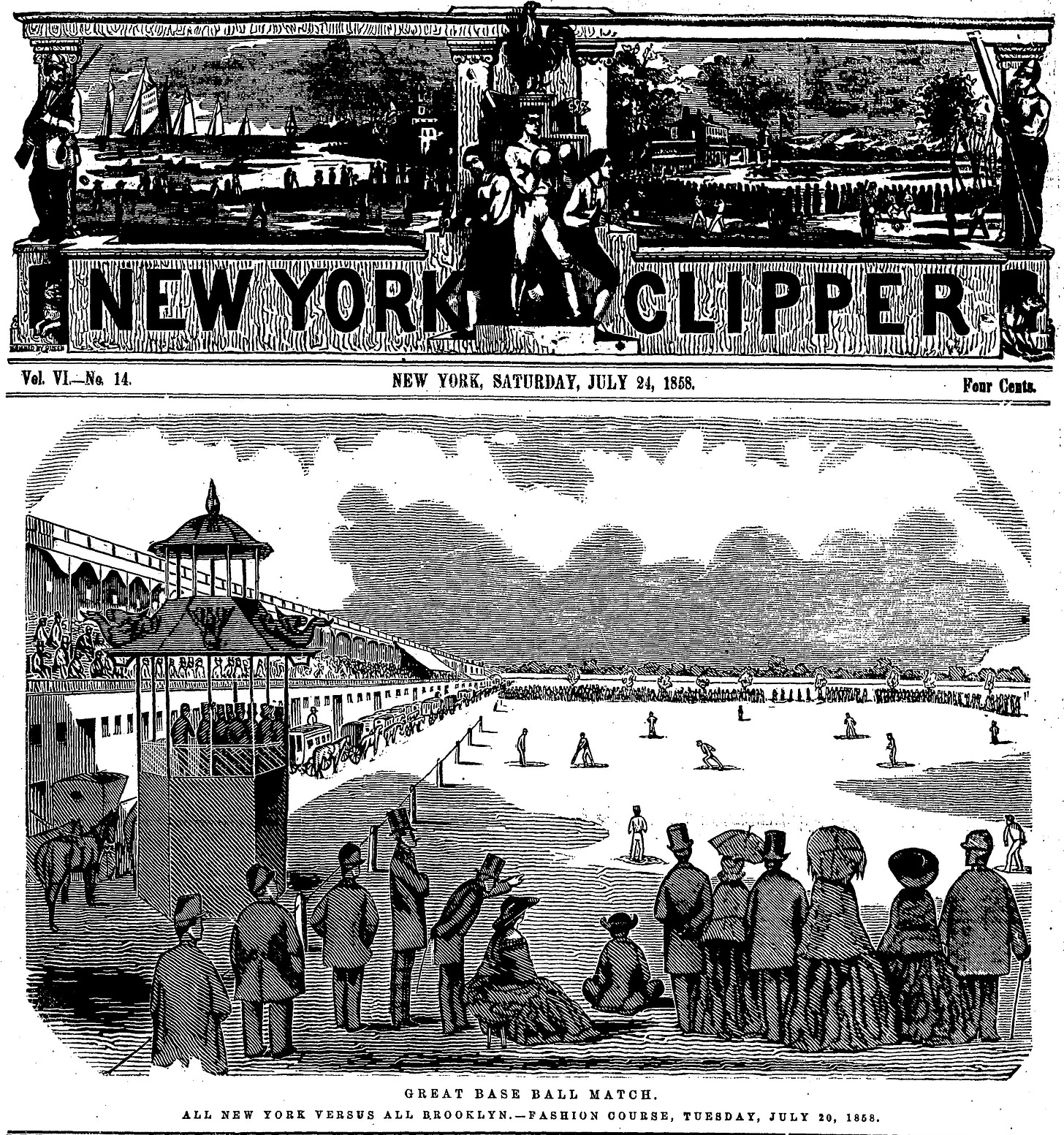

Last week, I wrote about Manhattan’s Madison Square where many of the rules of modern baseball were invented. It was on Corona’s race course, however, where the newly standardized game made its commercial debut. For the first time in history, people paid to watch a group of grown men run around a field hitting a ball with a stick.

Not only were the 1858 games the first to charge admission, they were also the first played in an enclosed park, and the first to pit two all-star teams against each other. Less than two miles from the Mets’ current home stadium, Citi Field, The New York All-Stars beat the Brooklyn All-Stars by a score of 2-1.

MY CORONA

In 1872, music publisher Benjamin W. Hitchcock bought much of West Flushing, including the old racetrack, and divided it into hundreds of lots for residential development. For a music publisher, Hitchcock, who also developed Ozone Park and Woodside, devoted a good chunk of his time to subdividing neighborhoods in Queens.

Most accounts credit Hitchcock with renaming the geographically accurate but undistinguished West Flushing to Corona, the “Crown of Queens.”

Others attribute the name change to Italian immigrants who moved into worker housing developed by the Crown Building Company.

LOUIS #1

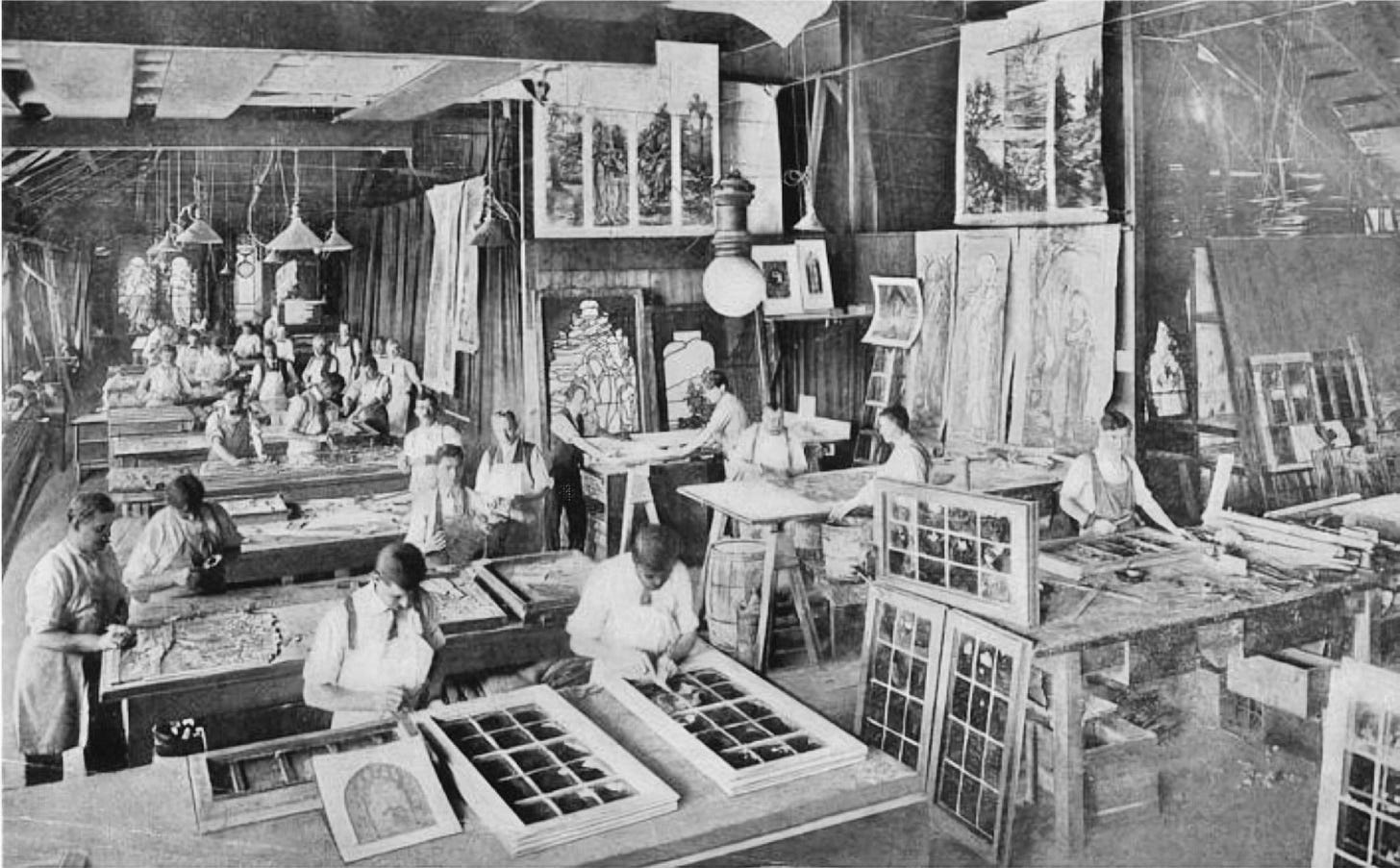

While Hitchcock’s subdivision sold moderately well, Corona was still pretty far off the beaten track. The secluded location, away from the prying eyes of his competitors, was the perfect spot for Louis Comfort Tiffany’s experiments in colored glass and pottery.

In 1893, Tiffany built a factory at the northwest corner of 43rd Avenue and 97th Place and perfected his patented Favrile glass. To manufacture the colored glass, Tiffany came up with a technique that infused molten glass with metallic oxides creating an iridescent surface.

Tiffany enjoyed enormous success until the 1910s when public tastes started to shift, embracing the modern lines and materials of Art Deco.

In 1932 Tiffany Studios filed for bankruptcy.

SATCHMO

By the time jazz legend Louis Armstrong and his wife Lucille moved into a modest two-bedroom house at 34-56 107th Street in 1943, Corona was home to a largely middle-class African-American and Italian immigrant population.

Armstrong, who Duke Ellington once said was “born poor, died rich, and never hurt a soul along the way,” was one of the most acclaimed performers of the time. He probably could have lived anywhere in the city but chose Corona.

There’s so much in “Wonderful World” that brings me back to my neighborhood where I live in Corona, New York… Lucille and I, ever since we’re married, we’ve been right there in that block. And everybody keeps their little homes up like we do, and it’s just like one big family. I saw three generations come up on that block…That’s why I can say, “I hear babies cry / I watch them grow / they’ll learn much more / than I’ll never know.”1

When the Armstrongs decided to give their house a brick facade, Louis went door to door and asked all his neighbors if they wanted him to pay to have their houses receive the same upgrade. Some of them took him up on it.2

Armstrong died in 1971, and five years later, the house was declared a national historic landmark.

Photographer Chris Mottalini took some fantastic photos of the house's interior a few years ago for the NY Times.

In 2023, the Louis Armstrong Center, the largest museum dedicated solely to one jazz musician, opened on 107th Street directly across from the Armstrong house.

Corona was something of a hotbed of jazz trumpeters. Besides Louis, Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry and Nat Adderley all called the neighborhood home.

'CAUSE WE ARE LIVING IN A FORMER YESHIVA

On 53rd Avenue, you can find the former residence of yet another music superstar: Madonna Louise Ciccone.

From 1979 to 1981, Madonna lived in the former yeshiva and sometimes synagogue with her then boyfriend Dan Gilroy and his brother Ed. She also played drums in their band, the Breakfast Club, before embarking on her solo career.

While living in Corona, The Queen of Pop earned quite a reputation from the locals.

tthe struggling singer was always turning up at the deli, trolling for freebies, wearing zany red lipstick, ripped jeans and fishnets.

“She never had a penny and would just hang around mooching sandwiches,” Giacomino said. “She still owes us a couple of bucks.”3

Despite never getting any help from their former bandmate, the Breakfast Club did have one hit, 1987's Right On Track, which has a pretty over the top video.

In the mid-90s, Dan Gilroy and Shelley Duvall (RIP) moved to Blanco, Texas. Ed Gilroy still lives in the house on 53rd.

By the time Madge moved out, Corona, formerly a majority Italian American neighborhood, was well on its way to becoming predominately Latino.

Conveniently, the former Italian neighborhood’s name means the same thing in Italian and Spanish.

CORONA PLAZA

In a sad irony, Corona was one of the epicenters of the city’s coronavirus outbreak. During the pandemic, Corona Plaza, a large open-air market under the 7 train, saw a huge uptick in vendors and customers. Restaurant critic Pete Wells (who recently announced his retirement) called it “the closest thing New York has to a market square in a small Mexican town,” ranking it No. 48 on his 100 Best Restaurants in New York City list.

Over 80 (largely unlicensed) vendors lured customers with puffy gorditas, mayo-slathered elotes, and steaming cups of champurrado. Last year, citing overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, Sanitation Department police officers descended upon the plaza and cleared out most of the vendors.

Since permits to sell food are notoriously hard to procure, a new system was put in place that allows vendors to get a restricted permit provided they have a food handling license and display a tax certificate. Today, a paltry fourteen vendors are allowed to set up shop in the plaza, and even on a busy summer Friday, the market is a shell of its former self.

SIGHTS AND SOUND

This week’s field recording is a walk under the 7 train, through the cacophony of Roosevelt Avenue ending with a YMCA sing along.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I’m always happy to have the opportunity to share more of Joel Sternfeld’s work. Here are a few more images from The Landscape as Longing project, which came from a 2002 Queens College commission to photograph Queens. Sternfeld and Frank Gohlke spent a year photographing throughout the borough.

Amazingly, except for Rinconsito Boliviano, which is now a Kumon, all these buildings are virtually unchanged in 2024.

NOTES

The recent hubbub around a performance of the national anthem during the All-Star home run derby had me wondering when the song became such a staple of baseball games.

The Star Spangled Banner wasn’t declared the national anthem until 1931. While there is evidence that the song was performed as early as 1897 on opening day in Philadelphia, it wasn’t until WWII that the notoriously hard-to-sing waltz became a fixture in ballparks nationwide.

Perhaps the most controversial national anthem performance was delivered by Jose Feliciano. Before Game 5 of the 1968 World Series, the Puerto Rican singer/ songwriter performed the first free interpretation of the anthem.

America wasn’t ready for such a radical approach, and Feliciano soon found himself blackballed by commercial radio. For better or worse, Jose’s version sparked a sea change and laid the foundation for future interpretations, from Hendrix’s bombastic rendition at Woodstock (better) to Fergie’s histrionic performance at the 2018 NBA Al-Star game (worse).

I recently learned that Whitney Houston’s version at Superbowl XXV, widely cited as the greatest of all time, was lip-synced.

Ultimately, though, Jose Felicano walked so Pamela Bell could run:

While Feliciano’s rendition of the national anthem is fantastic, his interpretation of Every Breath You Take …not so much. Feliciano’s performance at 2017 Polar Music Prize is worth watching for Sting’s reaction alone.

https://thesciencesurvey.com/spotlight/2022/03/16/the-home-of-louis-armstrong-a-peek-into-the-influential-jazz-figures-house-and-times-in-corona-queens/#:~:text=Yet%20Armstrong%20could%20not%20be,that%20high%20society%20never%20could.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/20/t-magazine/louis-armstrong-home-queens.html?unlocked_article_code=1.7k0.hFlQ.HxC7gz79xej9&smid=url-share

https://nypost.com/2001/06/12/they-dont-worship-madonna-her-old-corona-neighbors-recall-future-star-as-stuck-up-sponger/

I came for the stellar writing and was surprised with Madonna facts! So neat! Feliciano's rendition of the anthem is right up my alley, and a much more approachable example of a song that set the note on "free" so high it was only achievable by a few select people. SUBTEXT.

Who would have guessed Louis Armstrong had such an awesome kitchen?