Manhattan’s Flatiron District is situated just north of Union Square and runs north through Madison Square Park, roughly between Sixth and Park Avenues. In defiance of the rigid geometry of Manhattan’s grid, Broadway cuts a diagonal path through the neighborhood, creating the triangular lot occupied by the area’s namesake, the Flatiron Buiding.

Why the neighborhood is known as the Flatiron District rather than plain old Flatiron is a mystery. Other neighborhoods with the district designation–Financial, Theater, Garment, and Meatpacking—are all tied to specific industries, but the Flatiron District is named solely for the famous building. At least brokers didn’t give the neighborhood the dreaded acronym treatment like they did for nearby NOMAD (North of Madison Square Park). A name like FLADIS, which sounds a little like erectile dysfunction medicine, probably would not have made it past the focus groups.

CEDAR CREEK

While the Flatiron Building gets naming rights, Madison Square Park is the area’s most significant cultural and historical landmark.

Before becoming the heart of Gilded Age Manhattan, the plot was just an isolated backwater, a murky swamp bisected by the meandering Cedar Creek on its way to the East River.

The future park was the city’s original potter’s field, first put into use in 1794 to bury the many unclaimed dead who had succumbed to yellow fever while at the nearby Bellevue infirmary. The plot was full after only three years, and a new potter’s field was established in Washington Square. A skeleton from the potter’s field was unearthed during excavation work in the 1930s. There are most likely bodies still buried there today.

In subsequent years, the land was used as both an arsenal and a home for juvenile delinquents called the House of Refuge, which moved to Randall’s Island after burning down in 1839.

THREE CORNERED CAT

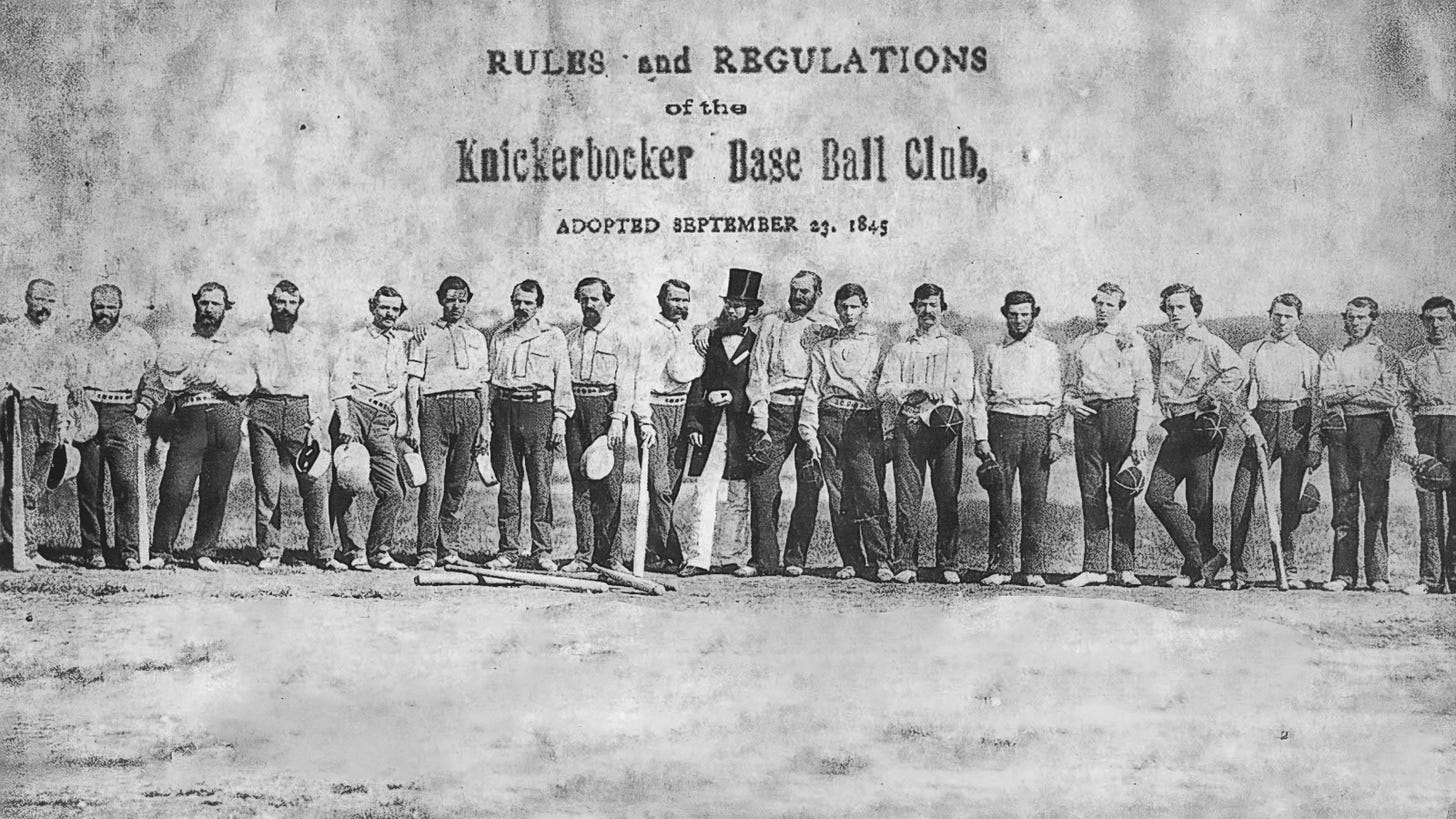

Although there is debate among baseball historians, many say the modern game of baseball was invented in Madison Square Park. It was there that members of the Gotham Base Ball Club and, later, the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club codified many of the rules of today’s game.

The New York clubs came up with the idea of using sandbags as bases, rather than stumps and boulders. The concept of the baseball diamond was also first introduced in Madison Square.

The practice of pegging a runner with a ball to get an out, a vestige from the child’s game, Three Cornered Cat, was wisely discontinued.

The ball was made of a hard rubber center, tightly wrapped with yarn, and in the hands of a strong-armed man it was a terrible missile, and sometimes had fatal results when it came in contact with a delicate part of the player’s anatomy

ILLUSTRATED LECTURES ON PUGILISM

Madison Square Park opened to the public in 1847, and in 1873, PT Barnum leased an abandoned lot adjacent to the park from Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had been using it as a railroad depot before moving it uptown. On the site, Barnum built a horse racing arena he called the Grand Roman Hippodrome.

In 1876, the building was leased to band leader and impresario Patrick Gilmore, a famous composer known as “The Father of the American Band.” According to the Times review from 1875, Gilmore spruced up the old Hippodrome considerably.

The work of transforming the unattractive Hippodrome into a lovely spot, where one can stand or sit amid green grass, fragrant shrubs, or thick foliage, has certainly been carried out with success. At one extremity of the building is a vast cavern, from the depths of which flows a cascade, sending its foaming waters to the promenaders’ feet. Here and there are large fountains; broad graveled walks wind about beds of flowers; platforms graduated to three or four rows of fauteuils.

All that landscaping wasn’t cheap, so to make ends meet, Gilmore resorted to hosting illegal boxing exhibitions. He got away with it by calling the boxers “professors” who engaged in "illustrated lectures on pugilism." Even with the workaround, Gilmore struggled to come up with the annual $40,000 rent, and the Vanderbilts took the building back.

WALK THIS WAY

While boxing may have brought in the crowds, it didn’t hold a candle to the most popular spectator sport of the late 19th century: walking. In 1879, the third competition for the Astley Belt, pedestrianism’s top prize, was held at Gilmore’s Gardens, where more than 10,000 gathered to watch Daniel O'Leary, Charles Rowell, Charles Harriman, and John Ennis walk in circles for six days.

On opening night, overwhelmed ticket sellers had to temporarily shut the gates. Hundreds of rabid fans, desperate for some of that sweet walking action, stormed the Garden’s doors. A phalanx of officers from 29th Precinct, under orders from Captain Alexander “Clubber” Williams, savagely beat the crowds back, precipitating a violent two-hour riot that sent 70 people to the hospital.

Despite the commotion, the four men inside the Garden continued their rotations, stopping only for short naps, chamber pot visits, and sips of brandy in their trackside tents.

O’Leary was the defending champ, and Rowell, the upstart Englishman, did everything he could to get in his head. One of Rowell’s strategies was to employ his effective but extremely annoying “dogging” technique, where he walked right behind O’Leary, constantly adjusting his pace and gait to match that of his opponent. Whether it was the dogging, his preference for champagne as a recovery beverage, a rumored poisoning by members of Rowell’s team, or simply a year’s worth of endurance walking catching up with him, O’Leary was the first to drop out of the race.

Later that evening, the balcony in the southwest corner of the building collapsed, sending over 100 spectators crashing into the crowd below. Remarkably, nobody was killed, and the race continued as if nothing had happened.

Eventually, Rowell won the belt, managing to walk 500 miles despite a hostile crowd and an atmosphere that the New York World described as a “Black Hole of smoke and stench and general stuffiness.”

If you want to learn more about the speed walking craze, be sure to check out Matthew Algeo’s fascinating book, “Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport.”

THE TRIAL OF THE CENTURY

In 1887, a group of investors, including J. P. Morgan, bought what was then called Madison Square Garden and hired starchitect Stanford White to design a new building. When the lavish Moorish-inspired Garden opened in July 1890, it was the biggest auditorium in the US, boasting the city’s largest restaurant and a rooftop cabaret.

It was on that same roof that Stanford White was shot by millionaire Harry Thaw at point blank range. Thaw, the erratic heir to a multimillion-dollar fortune, spent his considerable allowance on cocaine speedballs and indulging his widely publicized sadistic tendencies.

On that fateful night in 1905, Thaw was attending the opening-night performance of the musical Mam'zelle Champagne with his wife, showgirl, actress, and model, Evelyn Nesbit. Some years earlier, Nesbit had been in a “relationship” with White, a notorious womanizer thirty years her senior. Thaw, already convinced White had something to do with his being blackballed from New York high society, wanted revenge.

During a number titled "I Could Love a Million Girls," Thaw shot the architect three times in the face. In what was dubbed “The Trial of the Century,” reporters gleefully recounted salacious details that included Nesbit’s claim that White had raped her.

Thaw was found not guilty on the grounds of insanity and was sentenced to involuntary commitment for life in the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. He immediately went to work assembling a new legal team that would prove his sanity, a successful effort that saw him released in 1915.

In 1925, the New York Life Insurance Company, which held the mortgage on the Madison Square Garden site, tore it down to make way for its new headquarters. Today, Madison Square Garden, home to the Knicks, Rangers, and Liberty, is located in Midtown Manhattan.

A STINGY PIECE OF PIE

The Flatiron Building, designed by Daniel Burnham and completed in 1902, is one of New York City’s most iconic buildings. It is 285 feet tall but narrows to a mere 6.5 feet wide on its north-pointing tip.

Although the construction firm behind the project named it the Fuller Building, locals had been referring to the triangular site as the Flatiron for years and the name stuck.

While today, the Flatiron is one of the most beloved buildings in the city, it wasn’t always so. William Ordway Partridge, a better sculptor than architecture critic, called the building "a monstrosity, a disgrace to our city, an outrage to our sense of the artistic and a menace to life," while the New-York Tribune called the new building "a stingy piece of pie.”

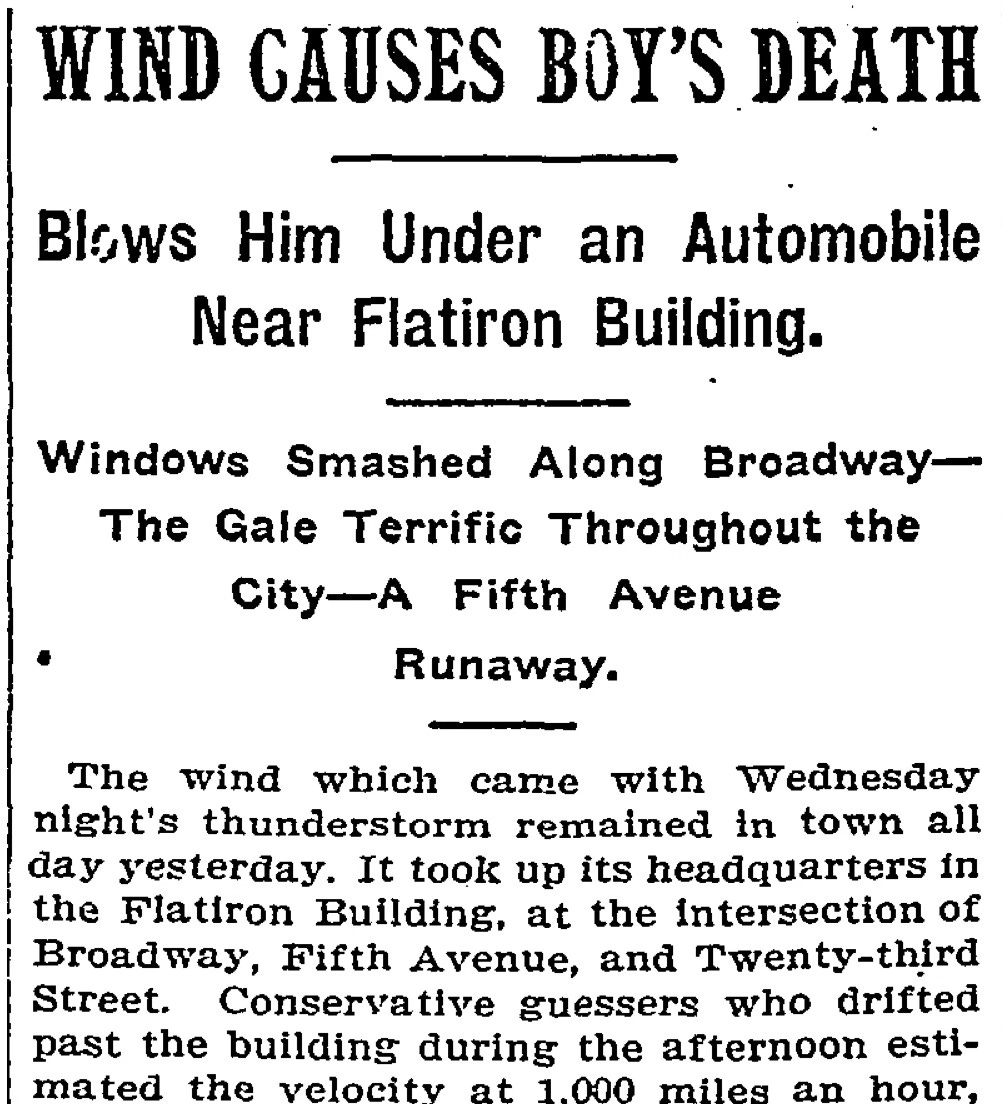

People used to avoid walking in front of the building, fearing it would collapse. In 1903, the notorius winds generated by the wedge-shaped design were blamed for the death of 14-year-old John McTaggart, who was blown off his bicycle under the wheels of an oncoming automobile.

While some feared the winds, a particular demographic welcomed them. Crowds of men would gather on the sidewalks of 23rd Street, waiting for a Flatiron-charged gust of wind to blow up an unsuspecting woman’s petticoats, affording them a quick glimpse of a bare ankle or, if they were really lucky, a knee.

The expression 23 Skidoo (the skibidi toilet of its day) was said to have originated with cops who used the exhortation to try and get the crowds of sleazy peeping Toms to disperse.

The Brodsky Organization is in the process of converting the Flatiron Building’s 22 floors into 40 luxury condominiums.

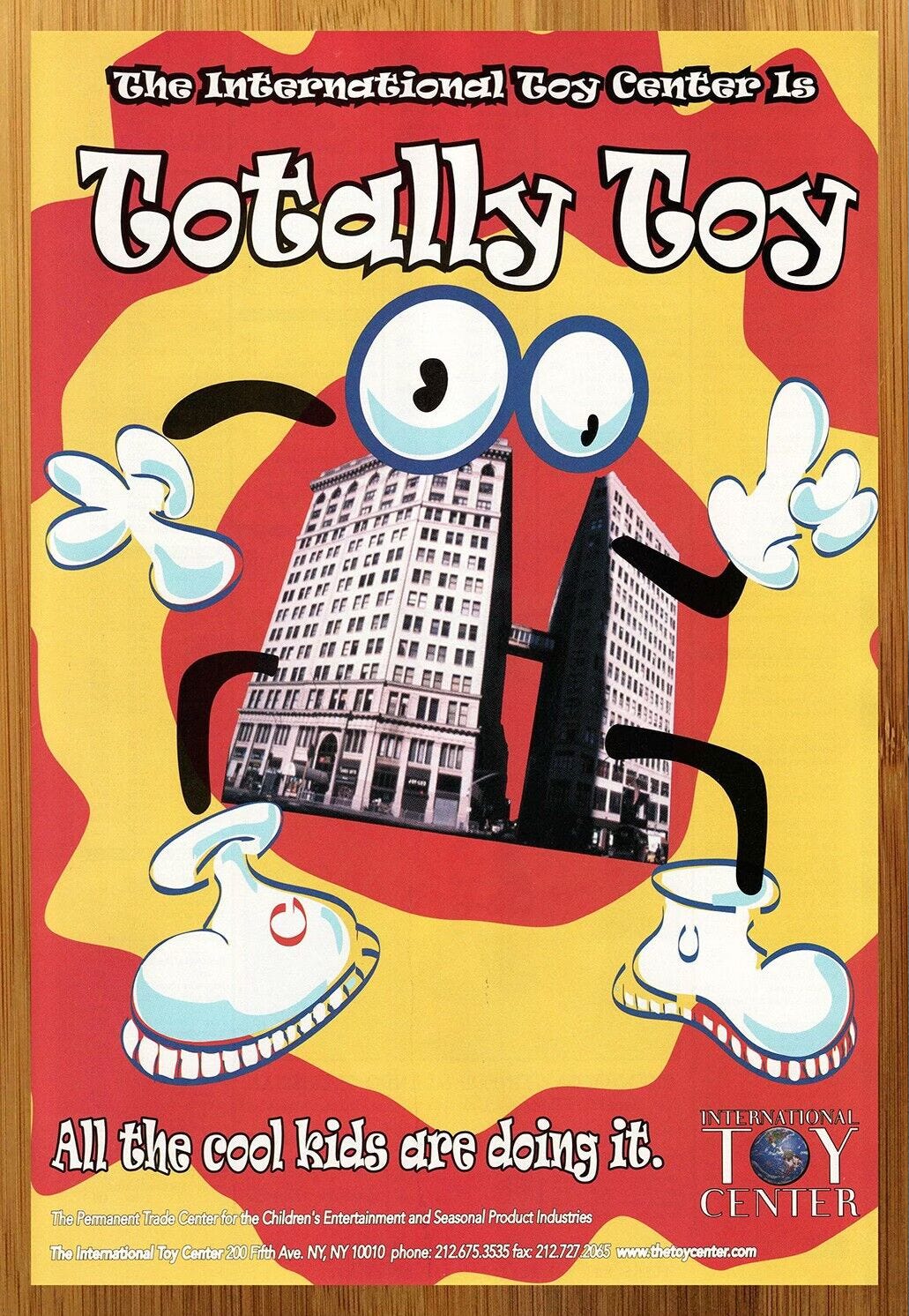

TOYS

Before the neighborhood was officially designated the Flatiron District in 1985, it was known as the Toy District. Every major toy company had their offices in the area, and by the 80s, the grand conjoined buildings between 23rd and 25th were filled to the rafters with Cabbage Patch Dolls, Hungry Hungry Hippos, and Teddy Ruxpins, accounting for 95% of toy transactions in the United States.

By 2010, most of the toy companies had moved out, and the Cabbage Patch Dolls were replaced by actual cabbage. Eataly, the upscale Italian food purveyor, opened its first outpost here, filling over 50,000 square feet with slices of bresaola, wheels of Grana Padano, and soon-to-be heavily discounted Mario Batali cookbooks. In a nod to the former tenants, a Lego store also occupies the ground floor.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

All of this week’s audio (and some of the pictures) come from a walk around the Chelsea Flea which is actually in the Flatiron District. Before you put on your headphones, be sure to grab a bottle of Wild Turkey and a pack of Chesterfileds.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

Luxembourg-born Edward Steichen is one of the most important figures in photographic history. For a long time, he was the most well-known and highest-paid photographer in rhe world. Steichen was also the director of photography at the MoMA from 1947 to 1962, where he curated the seminal Family of Man show in 1955.

Painter Of Nocturnes And Faces, Camera Engraver Of Glints And Moments, Listener To Blue Evening Winds And New Yellow Roses, Dreamer And Finder, Rider Of Great Mornings In Gardens, Valleys, Battles

Carl Sandburg's Poem to his Brother in Law Edward Steichen

Steichen made this platinum-gum exhibition print from a photograph he took of the Flatiron in 1904.

Another print of this same image was the second most expensive photograph ever sold, fetching $11,800,000 in 2022.

Here is a great short documentary from 1964 featuring a tremendously bearded Steichen and his three-legged beagle, Tripod.

NOTES

In a 2022 piece titled Landscape and Memory, Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias placed five cast bronze pools, bas-reliefs made up of rocks and roots, flowing with the water into the lawn at Madison Square Park, a reference to the creek that used to run through the area.

The most famous restaurant in the Flatiron District not named Shake Shack is Eleven Madison Park. The posh tasting menu-only eatery was originally opened by Danny Meyer in 1998. In 2017, it was named the best restaurant in the world and in 2011, chef Daniel Humm became co-owner.

When EMP re-opened after the Covid lockdown, it had become entirely plant-based. In his legendary review of the restaurant’s new direction, NY Times restaurant critic Pete Wells offers a particularly evocative description of a dish in which a beet is forced to do “things no root vegetable should be asked to do”:

Over the course of three days it is roasted and dehydrated before being wrapped in fermented greens and stuffed into a clay pot, as if it were being sent to the underworld with the pharaoh.

The pot is wheeled out to your table, where a server smashes the clay with a ball-peen hammer. The beet is cleaned of pottery shards and transferred to a plate with a red-wine and beet-juice reduction that is oddly pungent in a way that may remind you of Worcestershire sauce.

They used to do a similar beet act at Agern, a New Nordic restaurant in Grand Central Terminal, roasting it inside a crust of salt and vegetable ash. That beet tasted like a beet, but more so. The one at Eleven Madison Park tastes like Lemon Pledge and smells like a burning joint.

Anne Kadet devoted a whole issue of her Café Anne newsletter to the Portal, the glorified FaceTime call between Dublin and Manhattan that was put on restricted hours after a highly publicized flashing incident.

The best! My favorite newsletter

Clubber Williams, so named because of his proficiency with a nightstick, was the original Bad Cop. He regularly supplemented his policeman's salary with bribes and "protection" payments, which only protected the businesses associated with them from his wrath.