Nearly one quarter, or 3,000 acres, of Manhattan is built on landfill. The whole process started in 1683 when the British, fearing a French attack, dumped a bunch of dirt into the harbor to create a platform for their cannons. That mound of dirt would become Battery Park.

But it was Governor Thomas Dongan’s charter, issued in 1686, that really hastened the engorgement of the island. The charter allowed prospective buyers to purchase land extending 200 ft beyond the low-tide mark. Once the rights were acquired, the new owners would build underwater retaining structures and fill them with rocks and whatever garbage they could get their hands on, a process known as wharfing out.

With the passage of the Commissioners Plan in 1811, the remaining natural contours of Manhattan’s shoreline were subsumed by the rigid geometry of the newly imposed street grid. This Egbert Vielé map from 1865 shows the infilled edges of Manhattan in pink in contrast to the island’s original shoreline.

The map doesn’t show Battery Park City, which, one hundred years later, would become yet another layer in the urban strata.

EDIFICE COMPLEX

In the 1950s, Manhattan looked a bit like those grade school diagrams of a paramecium with rows of piers encircling the island's tip like cilia.

Most of those piers were obsolesced by a global transition to larger container ships, vessels that required the deeper berths of New Jersey’s ports. The piers soon fell into disrepair.

When local bureaucrats first conceived of Battery Park City in the early 60s, it was proposed as a way to solve several problems simultaneously: clean up the derelict piers, revitalize lower Manhattan with new housing and amenities, and serve as a repository for all the dirt and debris that was going to be excavated for the nearby World Trade Center.

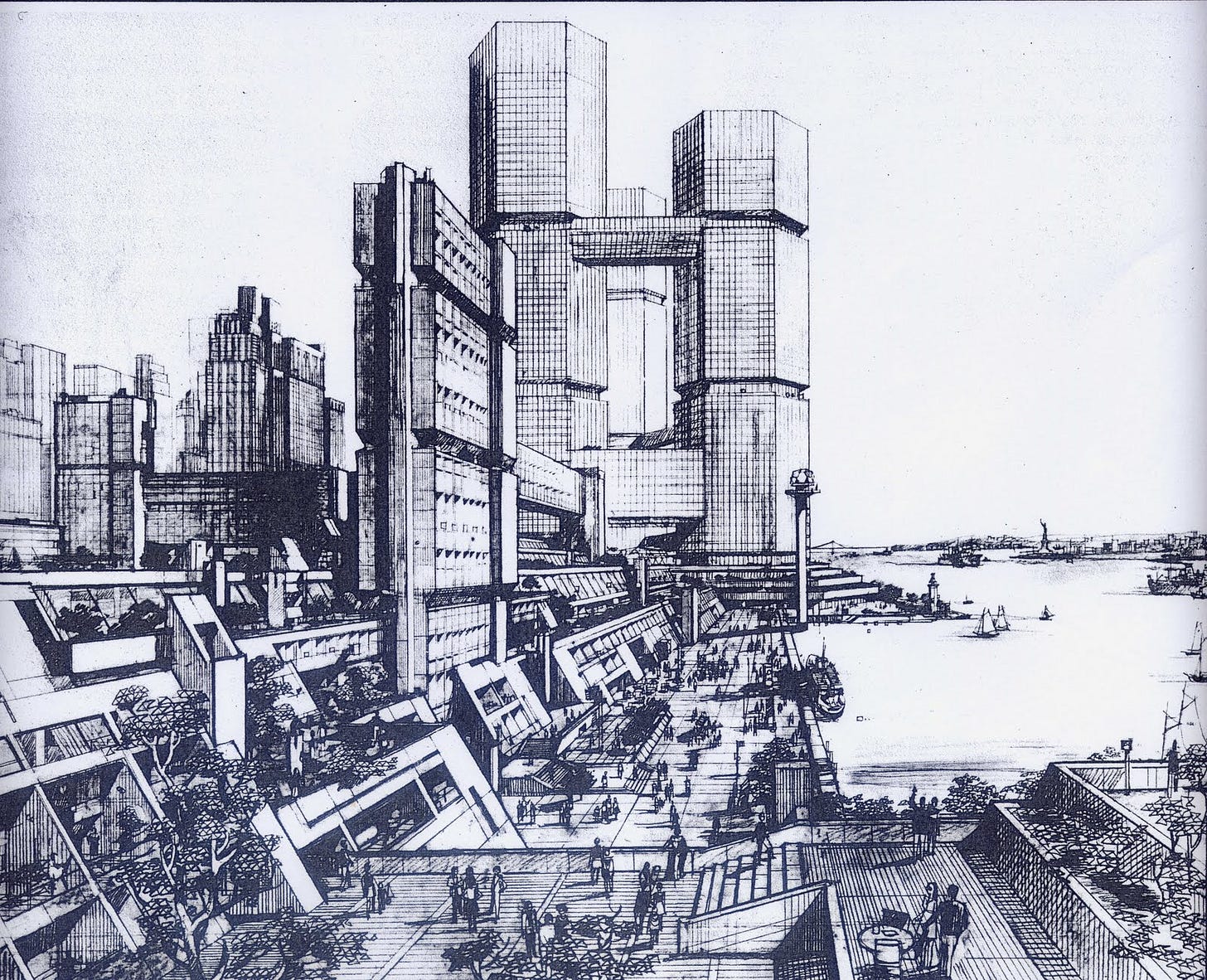

In the mid-60s, Governor Nelson Rockefeller shared his own vision for Battery Park City. Rockefeller brought in Wallace K. Harrison, the lead architect for the UN Headquarters and Lincoln Center, to help bring his plan to life. The two had recently collaborated on the much-maligned Empire State Plaza in Albany, New York, a project that earned Rockefeller the reputation of having an “edifice complex.”

New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable minced no words in her assessment of Rockefeller’s plan for Battery Park City:

a heart chilling cliché of standard towers in a non‐environment of vacuous spaces, a familiar formalism grew weary and stale since the 1930s when it was hot from Le Corbusier.

Another critic of the proposal said, “The early drawings were appalling — it looked like they were floating Co-Op City down the Hudson.”

Eventually, Rockefeller joined forces with Mayor Lindsay, and together they created the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA). The BPCA took control of managing the site, a role they still maintain.

The project, conceived only a few years before the city declared bankruptcy and necessitating input from the Governor, the Mayor, several architects, contractors, and multiple city agencies, was, unsurprisingly, slow to get off the ground. For a long time, the site was nothing but a wharfed-out 92 acres of dirt and sand.

WHEATFIELD - A CONFRONTATION

When Agnes Denes saw those 92 acres, she did what any midwestern farmer would do: she calculated how much wheat she could grow there. But Agnes isn’t a farmer; she is a conceptual and environmental artist, and her project, Wheatfield - A Confrontation, is considered one of the most significant artworks in New York City history.

In May of 1982, Denes, with the help of volunteers and a grant from the Public Art Fund, planted two acres of hard, red spring wheat on the edge of the West Side Highway.

My decision to plant a wheat field in Manhattan instead of designing just another public sculpture, grew out of the longstanding concern and need to call attention to our misplaced priorities and deteriorating human values. Placing it at the foot of the World Trade Center, a block from Wall Street, facing the Statue of Liberty, also had symbolic import.... It represented food, energy, commerce, world trade, economics. It referred to mismanagement, waste, world hunger and ecological concerns.

The field yielded over a thousand pounds of wheat, much to the delight of the city’s equine police population, the primary beneficiaries of the harvest. The seeds were later distributed worldwide.

I recently learned that in 2014, Denes unveiled a plan to plant 100,000 trees on what she called “New York’s last open space,” the Edgemere landfill in Far Rockaway, Queens.

POETS HOUSE

Today, Battery Park City feels more like a suburban office park than a city neighborhood. Everything is shiny and new. The buildings have no patina, no history except for the debris they are built upon. It feels strangely empty. There’s a mall.

.

The neighborhood is full of urban echoes, somehow desolate even when the day winds down and the cheerful crowds have trickled into the parks, the playgrounds, the public squares. From the outside, the brick-and-glass, block-wide buildings, though not very high, seem lifeless and oversized. It is as if the plan, the model, the map, the index, had never materialized into the thing itself; as if everything was still just a simulacrum in the mind of an architect - Valeria Luiselli

Still, it has a lot going for it. The neighborhood has fantastic views and beautiful parks. There’s the Skyscraper Museum and the Museum of Jewish Heritage. There’s even an IV nutrient therapy lounge.

It’s quiet. And, it has Poets House.

Poets House is a library containing over 70,000 volumes of poetry, including virtually every American poetry collection published since 1990. The video below shows Bill Murray reading poems to workers during the library’s construction.

Murray, a big poetry buff, made a seed grant for the Poets House collection. After shutting down for COVID-19 and a major flood, Poets House reopened just this last week.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

Today’s field recording starts off in the Irish Hunger Memorial, moves on to the banks of the Hudson during a rainstorm, and ends up at a summertime little league game.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAHER - Thomas Hoepker

Thomas Hoepker was born in Munich in 1936. He worked for Stern magazine as both a photojournalist and art director. Hoepker became a member of Magnum Photos in 1989 and served as the agency’s president from 2003 to 2006. His most famous image is of a group of young people in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, “sitting in the bright sunshine of this splendid late summer day while the dark, thick plume of smoke was rising in the background.” Taken on September 11th, it was a controversial picture, one that the photographer didn't share for several years.

1983 was a very productive year for Hoepker. This wonderfully surreal image was taken then, shortly before construction on Battery Park City began

Here are some more of Hoepker’s 1983 photographs:

NOTES

The last Art on the Beach event before construction began featured a solstice performance by Sun Ra and his Arkestra in front of David Hammons’ Delta Spirit House, a shack of found materials he built with Jerry Bar and Angela Valerio.

I couldn’t find a recording of that concert, but I did find this recording of Sun Ra and Don Cherry from a 1989 Solstice performance in Battery Park City, which, if you are into this sort of thing, is amazing. 5/5

Here is a neat interactive map made by the Smithsonian where you can move a little loupe over the Manhattan coastline and see a before and after.

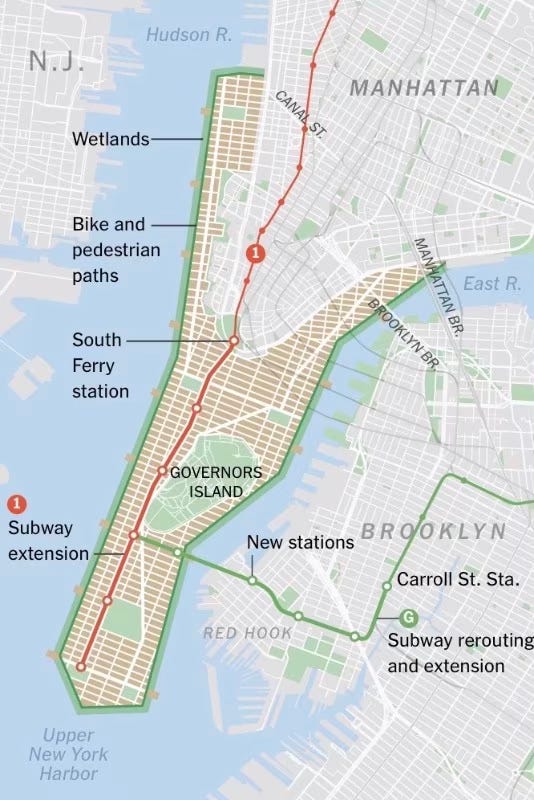

A couple of years ago, in a New York Times Op-Ed (gift link), Rutgers professor Jason Barr proposed adding 1,760 acres of reclaimed land to the tip of Manhattan. Barr claimed his “New Mannahatta” could provide housing to nearly a quarter of a million people while acting as a flood barrier for much of lower Manhattan. This is just the sort of insane idea that Mayor Eric Adams might get behind.

Not to be outdone, my new hero, Agnes Denes, put forward her own plan to ameliorate the effects of climate change on New York City. She has proposed building a series of giant dunes in Rockaway and barrier islands in New York Harbor. I’m going with Agnes’ plan.

BEFORE/AFTER

I’ve always loved this Mitch Epstein photo from 1977.

From now on, instead of “going bananas,” I’ll be “wharfing out!”

Fascinating read, thank you Rob! What a shame (for me at least) that the original Harrison plan never came to fruition.