Whenever people hear about this project, they inevitably ask about my favorite neighborhood. My stock answer is, "Whatever neighborhood I'm writing about this week." It's kind of a cop out, but it's the truth. Spending hours researching, writing, looking at, and listening to a particular place endears me to it, even if just for a week.

So, If you asked me this week what my favorite neighborhood is, I would answer Brooklyn's Vinegar Hill. But really, it has been one of my favorite neighborhoods since I first visited it some twenty-odd years ago. The Belgian block-lined streets, the sun glinting off the looming smokestack, and the idiosyncratic tableaus of the storefront windows—it's the kind of place I secretly wish I lived.

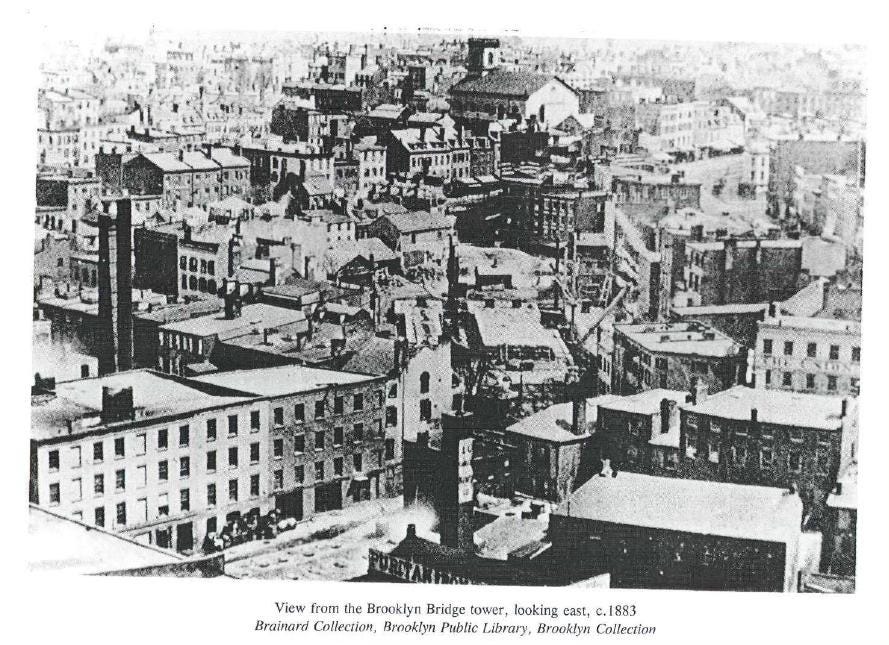

The quiet streets of Vinegar Hill, tucked between the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Manhattan Bridge, are some of the oldest and most storied in the city. The area has been known by many names, including Olympia, Irishtown, or, simply, the Fifth Ward. Just don't call it DUMBO. Unlike its flashy sibling to the west, Vinegar Hill is blissfully free from the throngs of matcha-sipping, duck-lipping tourists who bring traffic to a standstill in their quest to capture the perfectly framed under-the-bridge selfie. For now, the rampant development that has made DUMBO the most expensive real estate in the borough has largely been held at bay. After all, who wants the decaying chimney of a massive Con Edison Generating Station in the background of their selfie?

Vinegar Hill’s borders are between the Navy Yard and Bridge Street and the East River and the BQE.

OLYMPIA

The Sands brothers, Joshua and Comfort, made their fortune provisioning the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. General Washington was not a fan, calling Comfort Sands "a practitioner of dirty tricks" and accusing the brothers of supplying the army with spoiled flour, impure rum, and "exceedingly bad beef."

Still, being an unscrupulous military contractor was better than being a British Loyalist, and in 1748, the Sands brothers were able to purchase 160 acres of land on the edge of Wallabout Bay that had been seized from the Rapeljes family. The Rapeljes, who Russell Shorto called the Adam and Eve of New Netherland, had bought the land from the Canarises in 1637, but their support for the British drove them out of their Breukelen Eden.

With dollar signs in their eyes, the Sands brothers envisioned their new purchase as both an aristocratic retreat and a potential commercial district. They called it the "City of Olympia."

Surrounded almost with water ; the conveniences are almost manifest. A considerable country in the rear affords the easy attainment of produce. A pure and salubrious atmosphere, excellent spring water, and good society, are among a host of other desirable advantages. As regards health in particular, it is situated on the natural soil — no noxious vapors, generated by exhalations, from dock-logs, water, and filth sunk a century under its foundation, are raised here.

After they surveyed the land, the Sands sold several plots to a group of Connecticut families involved in the maritime trades.

In 1800, merchant and developer John Jackson bought the easternmost portion of the Sands property and built a small shipyard and housing for workmen. He named the area Vinegar Hill after the last battle of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 in hopes of enticing recently arrived Irish shipwrights to settle there. His plan worked, and soon, the new neighborhood was thriving.

IRISHTOWN

This first wave of Irish immigrants was superseded by a second, significantly larger surge of immigrants escaping the Great Hunger that swept through Ireland in 1845. Those who survived the harrowing cross-Atlantic journey aboard under-provisioned and overcrowded boats known as "coffin ships" had no choice but to settle where they landed. In many cases, that was literally adjacent to the port where their boat docked. Vinegar Hill, situated between the Navy Yard and the Fulton ferry and already home to a small Irish expat population, saw a boom in settlement.

Unlike their predecessors, who came to the country due to political differences and were generally wealthier and better educated, this second wave of Irish immigrants—emaciated, disease-ridden, and, perhaps most objectionable, Catholic—were relegated to the bottom rung of New York's social hierarchy.

By 1855, more than one-quarter of Brooklyn's population had been born in Ireland. Though Vinegar Hill was far from the largest Irish settlement in the city, it was the most notorious, and soon, everyone was calling it Irishtown.

POITÍN

In the twisting alleys and crowded tenements of Irishtown, whiskey was the beverage of choice as "water was mainly used to wash with." In 1885, the neighborhood boasted 110 liquor establishments, mostly saloons.1

Stories of wanton drunkenness filled the headlines.

Take Mrs. Mary Ann Jordan, who, upon seeing her neighbor, James Nicholson, ascending the stairs of their building, struck and killed him with an iron bar. James' timing was unfortunate because, though Mary Ann had nothing against him in particular, she had left her apartment that evening determined to "kill the first man she met." 2

Then there was the gruesome Christmas Eve murder of George Clancy in 1893. After spending a quiet evening decorating a Christmas tree at home on 57 Hudson Avenue, Timothy McDermott's mother asked him to pick up a beer across the street at Daniel Kelly's saloon.

When he entered, Timothy saw George Clancy enjoying a drink at the bar. McDermott had a grudge against Clancy, whom he blamed for an accident that had befallen his brother several years before.

After purchasing the can of beer, he crept up behind Clancy and plunged a razor five times into his groin, severing both his femoral arteries. He ran home, dropped off his mother's beer, and fled down Little Street, where he cut the lines off a docked boat and rowed across the river to East Fourth Street. Shortly after arriving, too exhausted to put up a fight, he was apprehended by the police.

Almost all of the alcohol in these saloons was locally and illegally produced. Irishtown was famous for its dozens of underground distilleries, crammed into back alley shacks and apartment basements, cranking out batch after batch of poitín or rum.

Poitín is a heady concoction often exceeding 90% alcohol by volume. The beverage, also known as Morning Dew or Jersey Lightning, dates back to the sixth century when Irish monks started distilling it from malted barley.

After the Civil War, the government was in desperate need of cash and instituted an excise tax on all alcohol. By 1868, those taxes reached $2.00 a gallon, equivalent to $30 today. Naturally, the best way to avoid those taxes was to take your operation off the books. The illicit alcohol business proved very lucrative.

“Nearly all of them wore ‘headlight’ diamond studs, big as filberts and dazzling in their luminous intensity. Now and again you would see a boss distiller wearing a gold watch that weighed half a pound, with a chain long and ponderous enough to hang a ten-year-old boy by the heels. The bigger the watch, the heavier the chain, the better they liked it.”

WHISKEY WARS

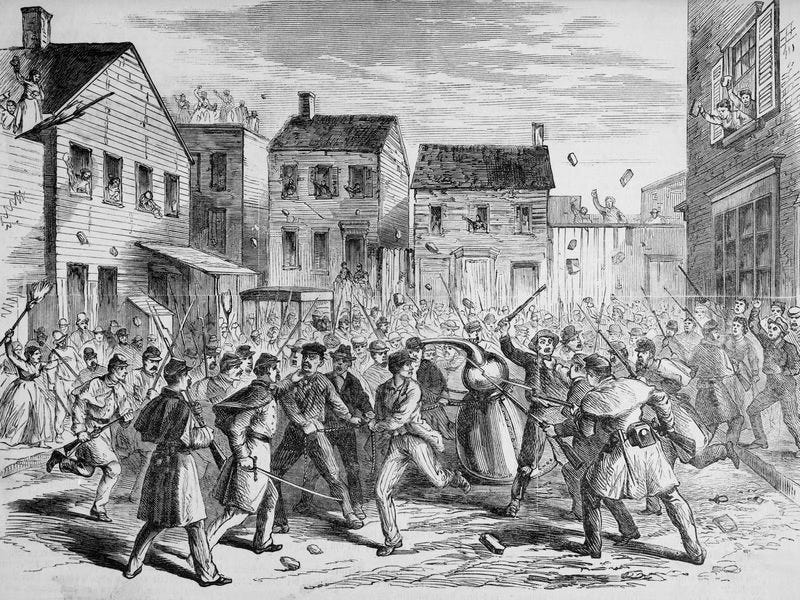

Throngs of tax collectors periodically descended on Irishtown to confiscate the illegal stills. Word of any impending raid often reached the neighborhood before the officers did. Locals, camped out on rooftops, hurled bricks, rocks, kitchen implements, and a coarse stream of invective down on the inspectors, who destroyed whatever equipment and booze they could find. The operations would be up and running again days later.

“a lively time was made by showers of stones and brickbats flying through the air. Every chimney and window seemed to have an enraged distiller behind it, who felt it to be his duty to break the head of at least one soldier.”

Eventually, the inspectors realized they needed more muscle, and on a snowy December day in 1869, 60 revenue officers were joined by 600 soldiers who made their way from the Navy Yard armed with axes and crowbars to make quick work of the neighborhood's brewing apparatus. They smashed stills and barrels and used fire engines from the Navy Yard to reverse pump the sour mash fermenting in vats into the streets. These raids continued, eventually culminating in an operation that saw over 2,000 marines fill the narrow streets and alleyways of the neighborhood. Very few arrests were made, but eventually, the repeated raids took their toll, and the distilleries shut down.

WHITE HAND GANG

The White Hand Gang was a coalition of Irish gangs that dominated the waterfront. They were united by their shared Irish heritage and by a deep-seated animosity toward the newly arrived Italian immigrants, whom they viewed as intruders encroaching on their territory.

The White Hand gang's most ruthless leader was "Wild Bill" Lovett, who held court in a longshoreman's bar at 25 Bridge Street. Bill, who once shot one of his own men for pulling a cat’s tail, “wrote Brooklyn’s criminal history with a broad-nibbed pen in the blood of slaughtered enemies.” In 1923, he was found dead in the back of the bar, his head crushed by a lead pipe.

His successor, Peg Leg Lonergan, was killed the day after Christmas in 1926 after deciding to insult a room full of Italians in the Adonis Social Club on 20th Street in Park Slope.

Unfortunately for Peg Leg, one of those Italians was Al Capone, who shot the gang leader and two of his associates, effectively ending the reign of the White Hands and marking a turning point in the control of Brooklyn's waterfront from Irish to Italian dominance.

SHIFTING SANDS

The neighborhood's transformation accelerated with the 1896 opening of the Sands Street entrance to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Sands Street instantly became a thriving commercial thoroughfare packed with sailors on leave and civilians looking for entertainment. The neighborhood's shifting demographics were reflected in the diversity of businesses on the bustling strip. There were Italian grocers, German butchers hawking wienerwurst, Japanese tattoo artists, and Jewish tailors who could repair sailors’ uniforms or rent them civilian clothes so they could more easily blend in. There were funeral parlors, photo studios, and, of course, plenty of saloons.

At night, the street transformed into what Thomas Campanella called "a rogue's gallery of establishments aimed at the wallets and loins of seamen—an unbridled mélange of gambling, prostitution, and general debauchery."

Poet Hart Crane spent many nights cruising the Sands Street strip, looking for companionship. In the 1920s, in an attempt to discourage sailors from patronizing the disreputable businesses along the thoroughfare, the Brooklyn Navy Yard Commandant ordered the closure of the Sands Street entrance.

“a shapeless grotesque neighborhood, its grimy cobblestone thoroughfares filled with flophouses, crumbling tenements, and greasy restaurants.”

The 1950 film "The Tattooed Stranger" captures footage from the last days of Sands Street, beginning around the 30-minute mark.

DAMN THE TORPEDOS FULL SPEED AHEAD

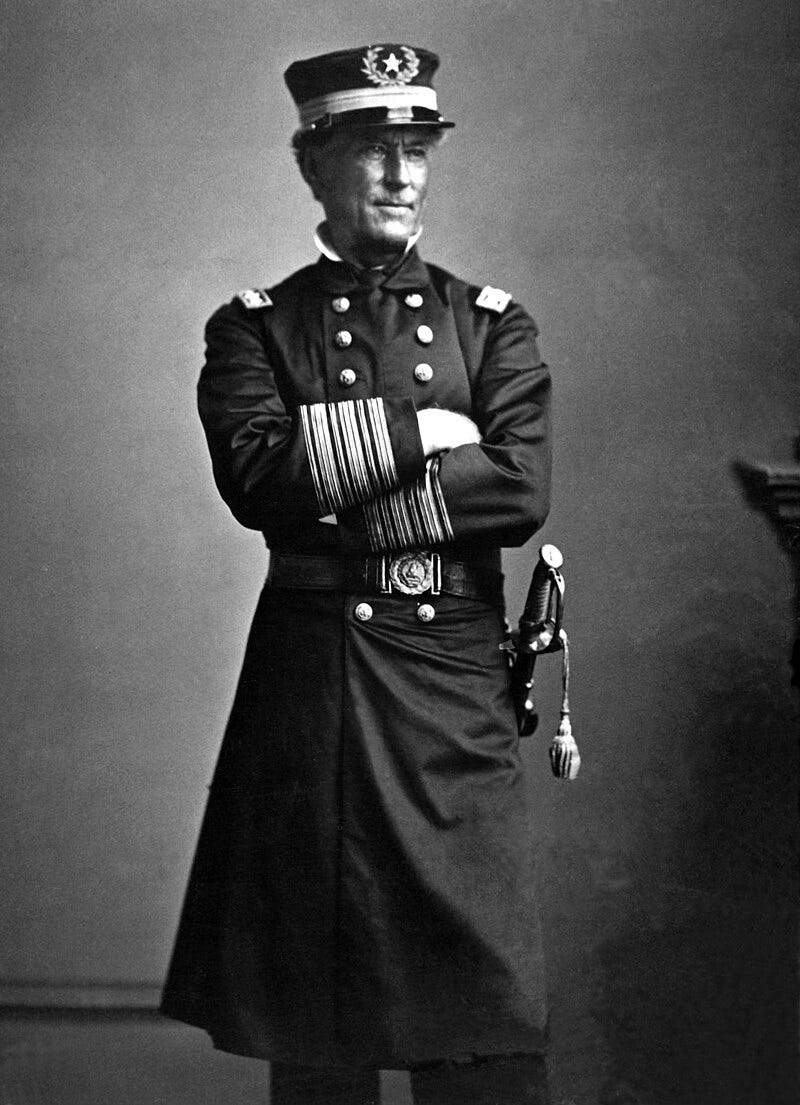

By the time "The Tattooed Stranger" was released, the dismantling of Irishtown was in full swing. In the name of slum clearing, large swaths of the neighborhood were razed to facilitate the construction of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway and the Farragut Houses.

The ten 14-story buildings of the Farragut Houses, which opened in 1952, displaced over 200 businesses and 1800 residences.3

The housing project was named after Admiral David Farragut, famous for his quote, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead." It's the kind of aphorism that epitomizes the ethos of the man largely responsible for clearing Irishtown, Robert Moses.

SMOKE ON THE WATER

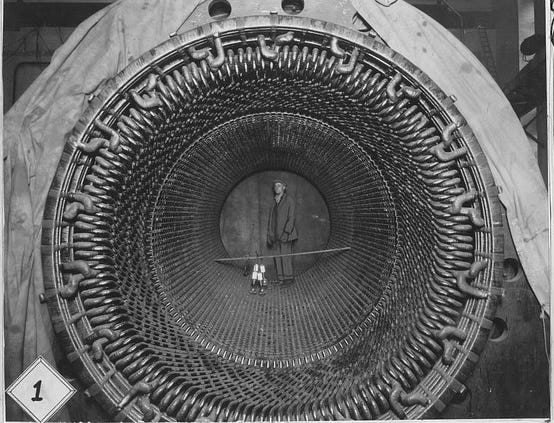

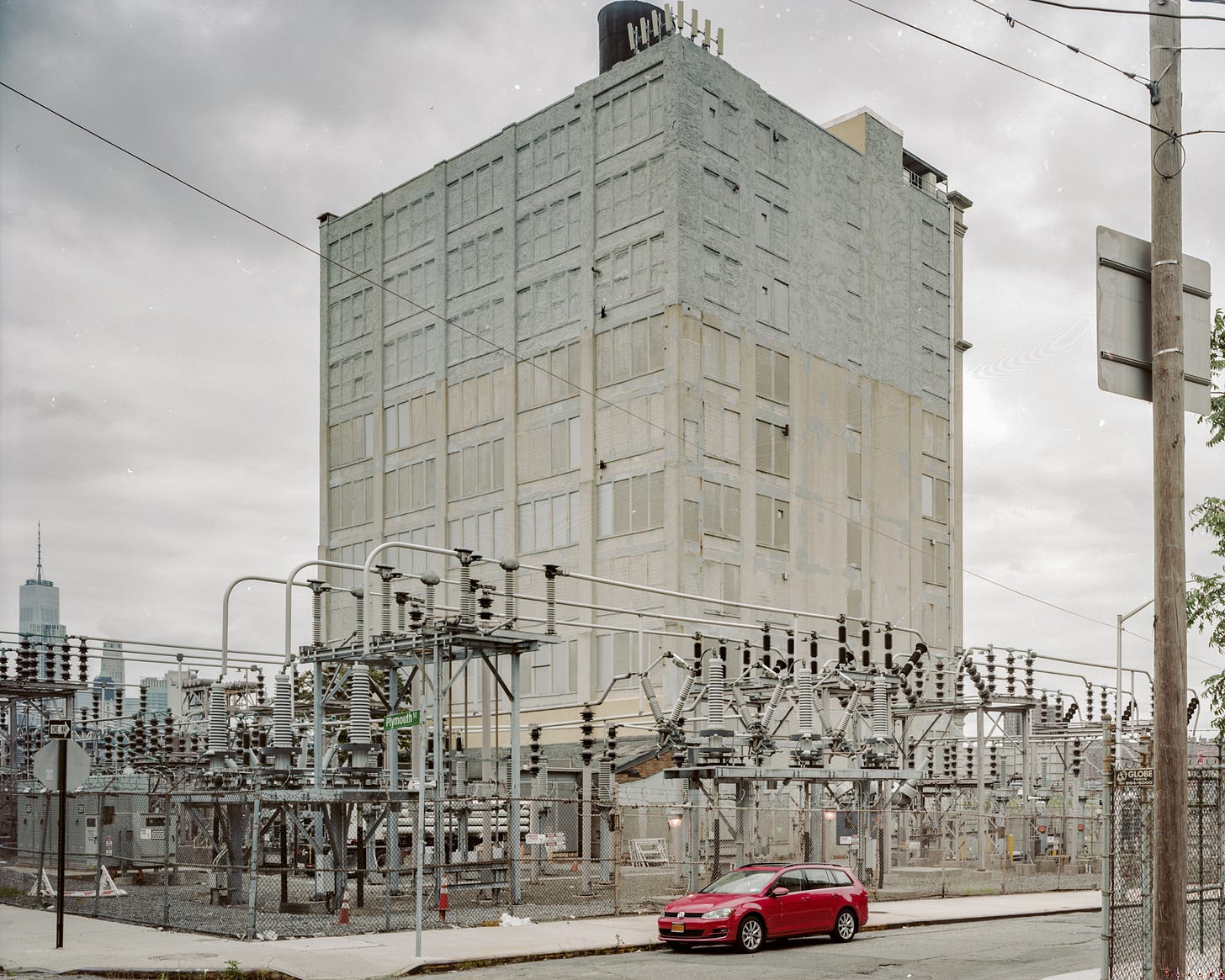

The first thing anybody notices when visiting Vinegar Hill is the giant smokestack that towers over the neighborhood, the last relic of the Con Edison Hudson Avenue Generating Station.

When completed in 1932, the station boasted the world's largest turbine, capable of producing 770 megawatts.

During its 80-year run, the massive cogeneration plant provided power to Brooklyn and Queens and steam to Manhattan. The plant closed in 2011.

Current plans are underway to convert it into the Brooklyn Clean Energy Hub, or simply "The Hub." The facility will process and deliver energy produced by offshore wind farms and will be capable of powering approximately 750,000 homes. Locals are skeptical.

Speaking of cogeneration plants, here is a great NY TIMES piece on Manhattan’s underground steam network.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s recording is rather minimal. Vinegar Hill is a quiet place, though on the day I was recording, it was extremely windy. You’ll hear the clangs of one of the many signs surrounding the Con Ed plant warning you not to photograph, a flock of birds that are fed by one of the tenants in the former home of femoral artery slasher Timothy McDermott, and lots of footsteps and heavy breathing.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I've loved Wayne Sorce's work ever since I first came across his iconic image taken on Hudson Avenue in Vinegar Hill.

Sorce was born in Chicago in 1946 and attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His late seventies and early eighties urban landscapes, made mostly in Chicago and NYC, capture the time so well. Sorce paid several visits to Vinegar Hill.

“For me, photography is very important in that it exists because of everything else. I hope this explanation is enough because I think it would be a mistake to write words to be read about that which I only intended to be viewed. Words only confuse and complicate what I prefer to bear witness to my feelings by visual means.” -Camera Magazine, November 1973

You can see more of Sorce’s superb photographs at the Joseph Bellows Gallery website.

NOTES

Hudson Avenue, the neighborhood’s main drag, only has two restaurants. - The Vinegar Hill House and Cafe Gitane

It also has an art gallery

The Forgotten Farragut is a documentary short that “examines the impact of Brooklyn’s wealthy DUMBO neighborhood upon the adjoining low-income community of Farragut Houses.”

91 Hudson Avenue was the original location of a vault containing the remains of the nearly 12,000 Americans who died in captivity aboard British prison ships anchored in Wallabout Bay during the Revolutionary War. In 1908, those remains were moved to the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park.

Though it’s technically in DUMBO, I wanted to mention my friend and sometimes guitar teacher, Derek Gripper, is performing tonight, just a half block away from the White Hands headquarters where “Wild Bill” Lovett was killed in cold blood. The concert, which should be free of gang violence, is a benefit for the World Music Institute, where (fun fact) I worked as an intern in the 90s. For more info: https://www.worldmusicinstitute.org/derek-gripper-wmi-benefit/.

https://www.bklynlibrary.org/blog/2021/05/18/story-sands-street?t

😆👍 to the caption, “There goes the neighborhood” with the cyber truck.

Great edition, Rob. I have cycled on Sands St. many times but had no idea of its history. Throughout the city, it's like every red brick public housing complex is a monument to the ghosts of an old neighborhood.

Given the number of distilleries that used to be in the area, it's fitting that the King's County Distillery is just inside the Navy Yard Sands St. entrance. I recommend their tour and tasting.