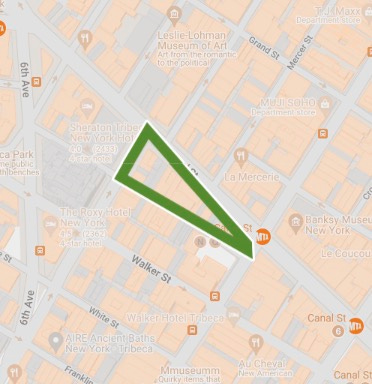

Although people have only been calling it Tribeca since the early 1970s, the trendy neighborhood on Manhattan’s Lower West Side is one of the city’s most historic areas. The name is an acronym for Triangle Below Canal, which, as far as these things go, is not so bad. (I'm looking at you, RAMBO). It also makes the usually murky science of determining a neighborhood's borders relatively straightforward - well, at least one of them.

When a neighborhood attains a certain cachet, realtors immediately attempt to enlarge its borders, annexing the territory of adjacent, less-coveted neighborhoods. In this case, Tribeca's new borders—Canal Street, West Street, Broadway, and Park Place—make the original name obsolete, as they form a quadrilateral. Still, the name stuck. Quabeca just doesn't have the same ring to it.

According to the New York Times, an artist cooperative invented the acronym, which, at the time, only applied to a modest triangle formed by Canal, Lispenard, Broadway, and Church Streets. The Times also attributes the name to a “whimsical geographer at the Office of Lower Manhattan Development,” so who knows?

A recent Street Easy campaign:

Given the neighborhood’s designation as one of the most expensive in the city, a liberal interpretation of its borders is inevitable. Not bad for a former swamp that was once described as a “receptacle for filth, a nest of crime, and in every respect a nuisance to the city.”1

A MIRY MORASS

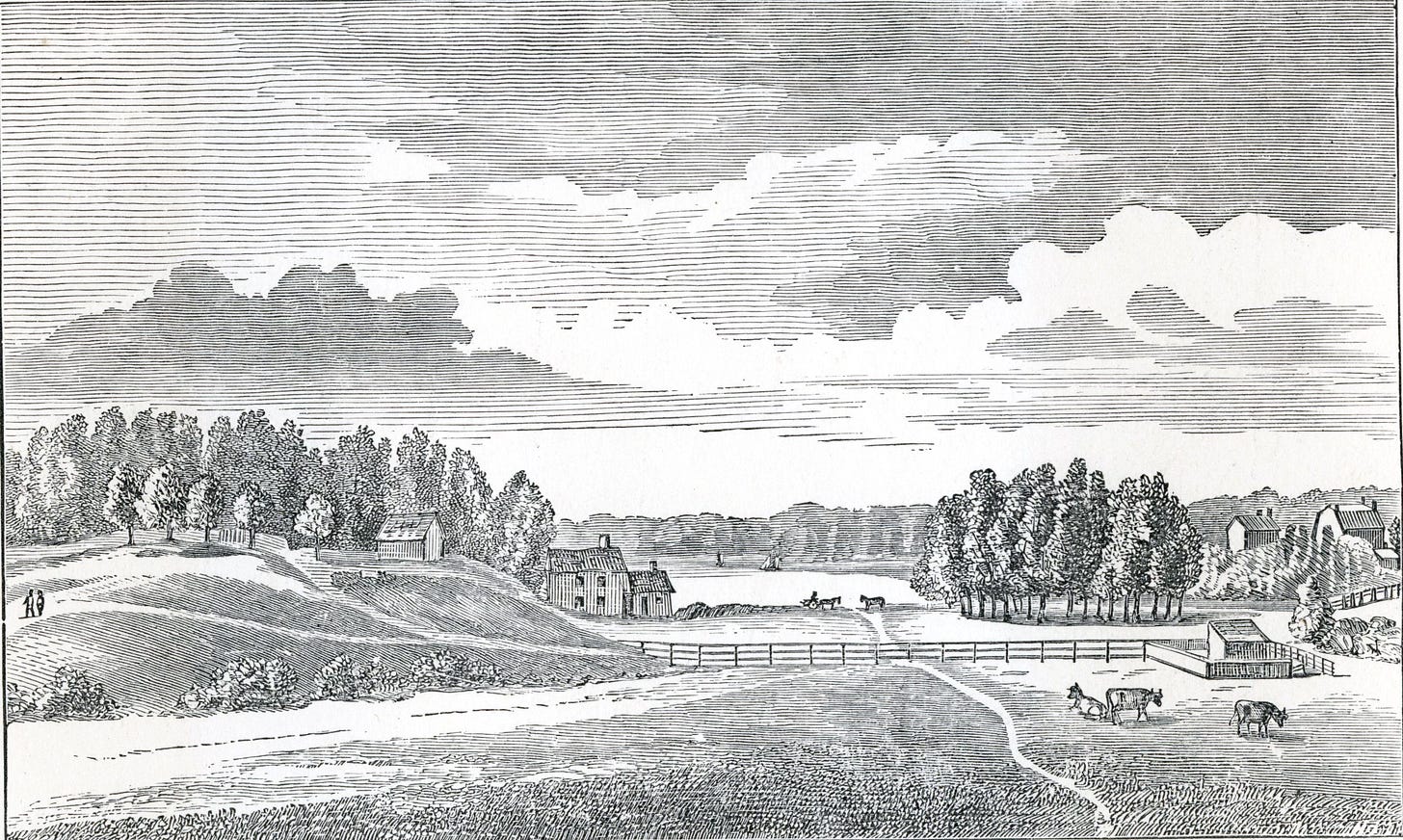

The western edge of Tribeca started underwater. A significant chunk of the rest of the neighborhood was swampland — salt marshes fed by a stream flowing out of Collect Pond, once the city's primary source of fresh drinking water.

This 1865 Egbert Viele map shows the original water courses and manmade additions to the shore.

In 1730, farmer Anthony Rutgers, who had a lease on a good bit of the marsh-covered land, proposed draining the swamp. Rutgers' proposal was not an ironic metaphor for subverting the Constitution and instituting a kleptocracy but rather, quite literally, an effort to get water out of the swamp, "a miry morass, covered with a thick growth of brush and such vegetation as is usual in wet and marshy soil. It was a patch of ground useless and dangerous alike to man and beast."

Rutgers, along with his son-in-law Leonard Lispenard, accomplished the task by digging a ditch that ran from the northern shore of Collect Pond to the Hudson. This ditch would later be widened and infilled, becoming the small canal that would one day become Canal Street.

When Rutgers died, Leonard wasted no time renaming the area Lispenard's Meadows.

ST. JOHNS

It was around this time that Trinity Church, perhaps inspired by the swamp's transformation, determined that the area could make them some money. As I wrote in the Hudson Square newsletter, Trinity Church was (and remains) one of the largest landowners in the city, and in addition to Hudson Square, their land covered much of modern-day Tribeca. The entire tract was known as the Church Farm.

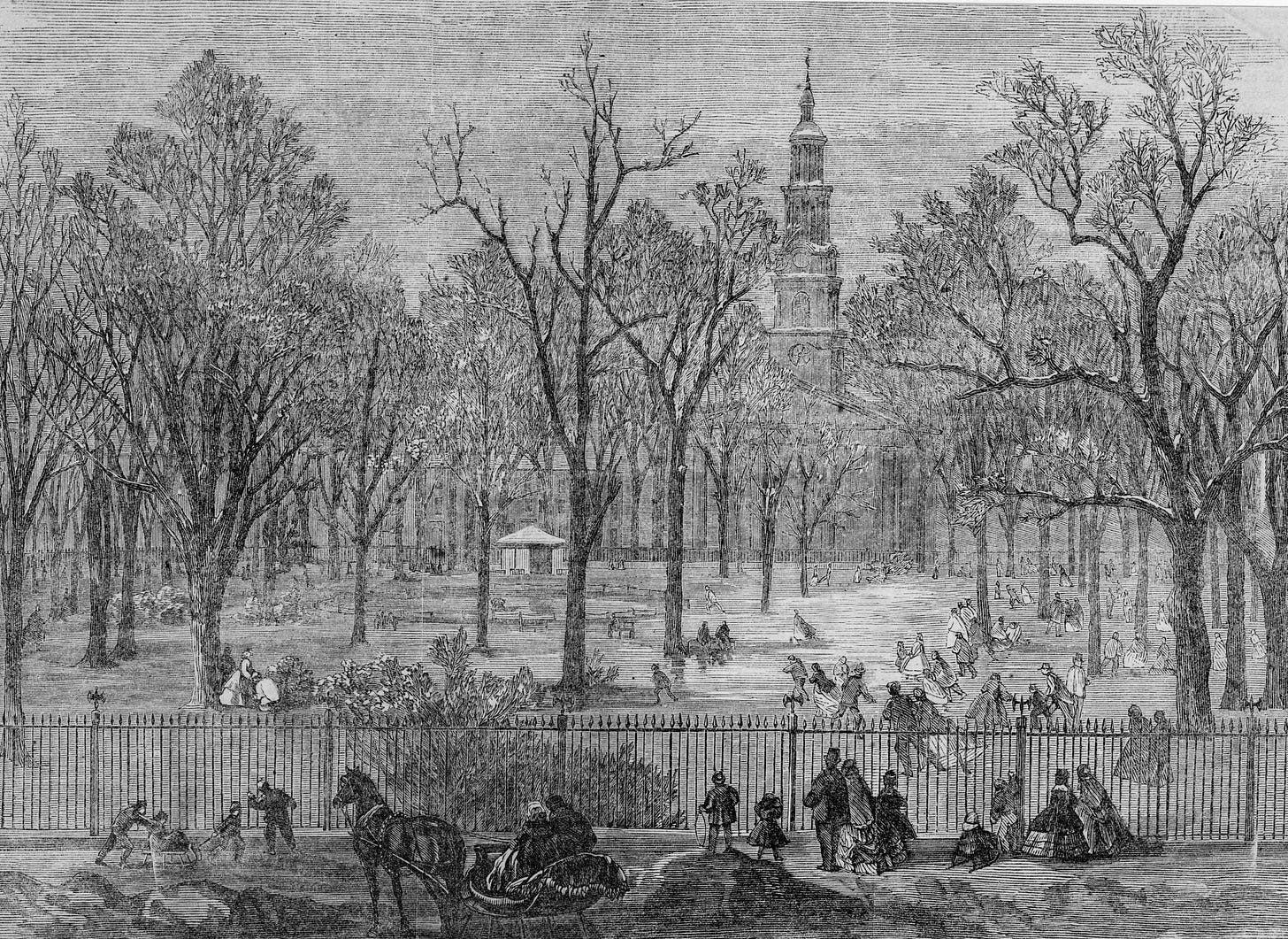

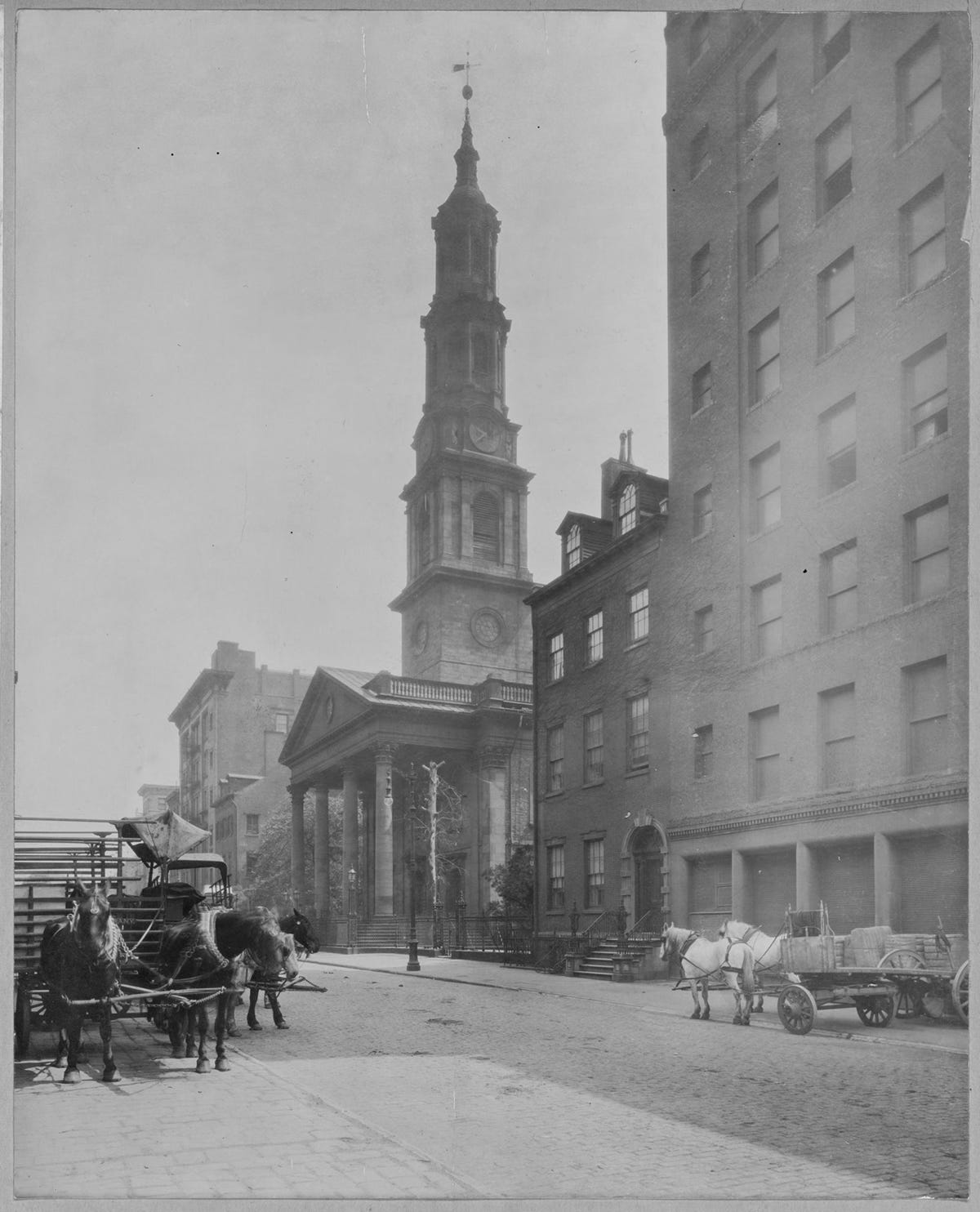

In 1803, to encourage development on their property, the church built St. John's Chapel and the adjoining St. John's Park, the first private square in the city.

Initially, the church offered 99-year leases, but New Yorkers wanted to own their property, and development stalled. Then, in 1827, the church sold the lots outright, setting off a buying frenzy. The posh enclave was soon one of the most sought-after addresses in town, the "headquarters of fashion," home to the Swifts and De Niros of their day. Local homeowners were given keys to the gated square where they could enjoy promenading the paths of pea gravel that wended their way around stands of horse chestnuts, silver birches, and landscaped flower beds without fear of rubbing shoulders with the hoi polloi who could only look longingly through the bars of the $26,000 iron fence that surrounded the park.

On rare occasions, when it was cold enough, the park was flooded and turned into a skating rink, and the general public was allowed in for 10 cents.

In just a few short years, however, the neighborhood fell victim to the "omnivorous appetite of improvement." The relentless and inevitable northward progression of the city enveloped the former suburb in the very grime and commotion its denizens had sought to escape. When Cornelius Vanderbilt purchased St. John's Park in 1867 and replaced it with a massive freight depot, what had been a neighborhood of "aristocratic dwellings was reduced to a slovenly purlieu of ramshackle buildings."2

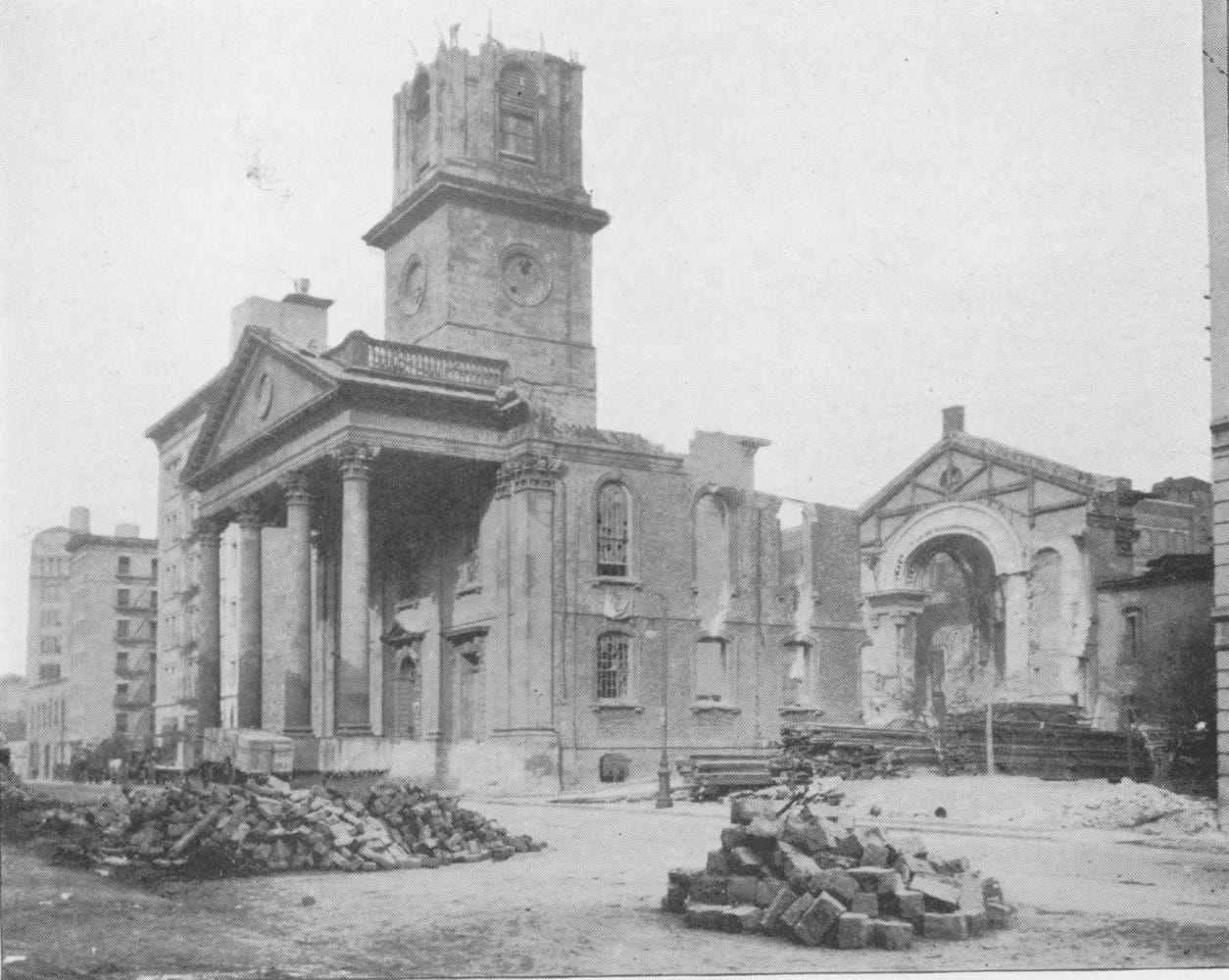

Most parishioners left St. John's Chapel in the 1890s, and in 1918, the church was torn down.

BEAR MARKET

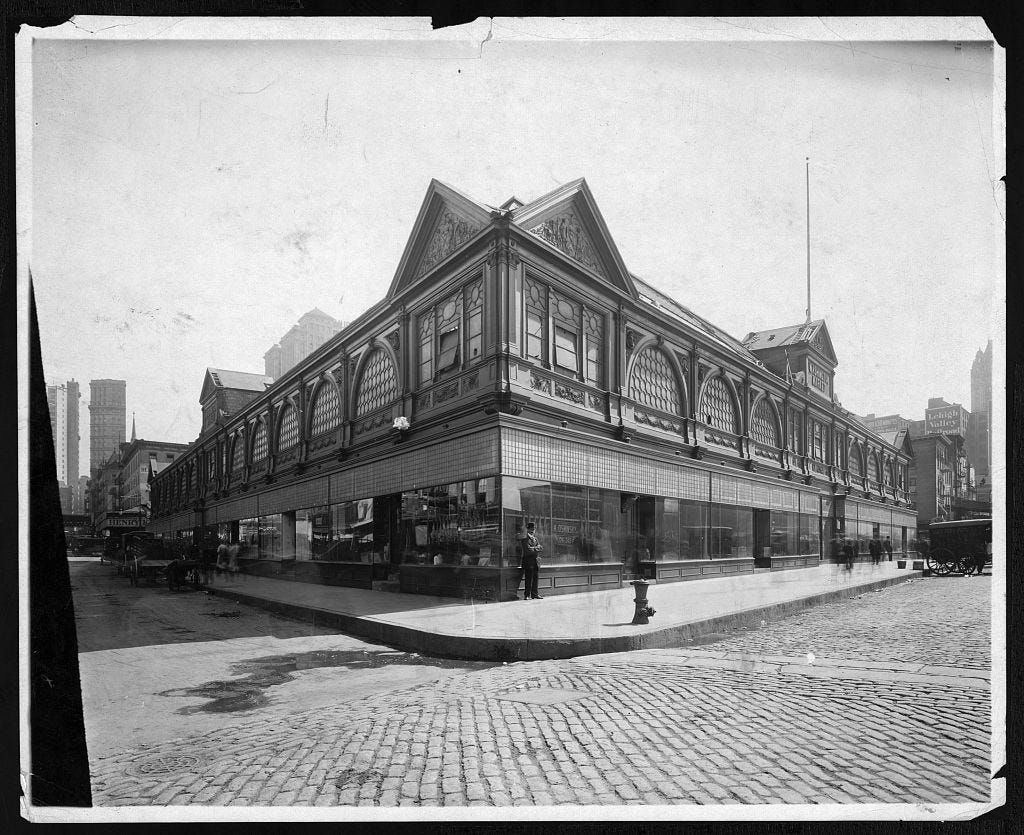

Vanderbilt's new freight terminal was, however, welcomed by the merchants and commissioners of Washington Market, which opened in 1813. What started as a piecemeal assemblage of pushcarts and open-air stalls would soon become the largest wholesale produce operation in the country. The market was originally known as the Bear Market, named after a bear who had the misfortune of exiting the Hudson River after a long swim from New Jersey in the vicinity of a contingent of skilled and eager butchers.

Like the bear, much of the produce came from New Jersey. The market's prime location on the banks of the Hudson, and later along the tracks of Cornelius Vanderbilt's railroad, made it a resounding success.

By 1853, sales at the rapidly expanding Washington Market exceeded $28 million, though that didn't stop the New York Times from calling it a "dirty, degraded little rat-hole." Like the overflow from the Collect Pond, businesses spilled outward from the railroad depot and the market, colonizing large swaths of the surrounding area. Massive cast-iron buildings, lofts, and warehouses—some of today's most coveted real estate—began to rise between the few remaining private residences, which had been converted into tenements and boarding houses for those employed in the market.

Writer Thomas A. Janvier was not impressed with the change:

Lines of dripping, soap-smelling washtubs are stretched along hallways, through which one might drive a coach and four; stovepipes are run into fire places in which one might set a dining table, and cot beds stand thick around parlors that look like ballrooms turned into rag shops…. The aggressive presence of several distinctively Neapolitan smells. The stately houses, swarming with this unwashed humanity, are sunk in such squalor that upon them rests ever an air of melancholy devoid of hope. They are tragedies in mellow-toned brick and carved wood-work that once was very beautiful.

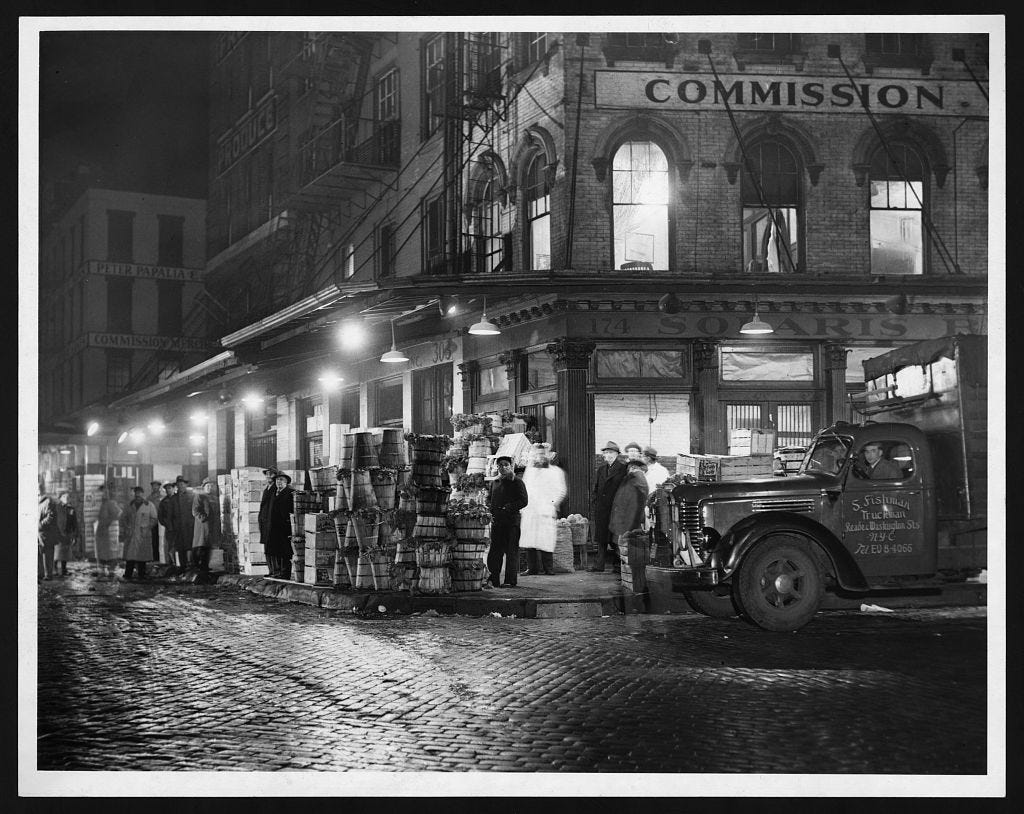

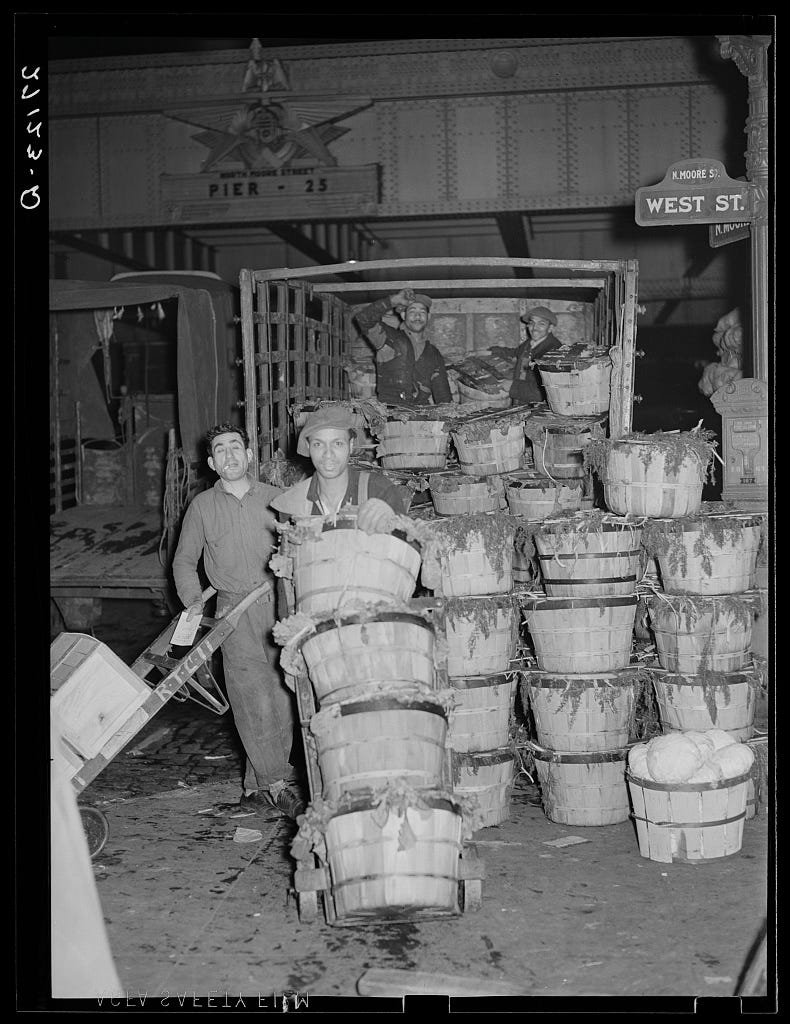

The market continued expanding and remained the largest food distribution hub in the city. It was a frenzied hive of activity that didn't spring into life until midnight, when convoys of trucks and wagons converged on the neighborhood, laden with crates of fresh figs, South African grapes, and Westchester mushrooms.

And it wasn't just produce. The WPA guide to 1930s New York City details a veritable cornucopia of goods on offer including "caviar from Siberia, Gorgonzola cheese from Italy, hams from Flanders, sardines from Norway, English partridge, native quail, squabs, wild ducks, and pheasants; also fresh swordfish, frogs legs, brook trout, pompanos, red snappers, codfish tongues and cheeks, bluefish cheeks, and venison and bear steaks."

The market was full of vendors who parlayed their experience with produce stalls into fruit fortunes. Take, for example, Max Leef, the "cantaloupe and honeydew melon king."3 Leef started with a simple pushcart on the Lower East Side, then moved into a small storefront before finally moving his operation to Washington Market, where he paid $36,000 a year in rent for his space. While that sounds like an exorbitant amount of money for 1927, Leef was the city's preeminent melon middleman, with roughly three-quarters of all the melons consumed in the city passing through his warehouse. He was said to have made over one million dollars.

There are no melons in the below picture, but tell me that the guy on the left isn't the spitting image of Tribeca’s most famous current resident…

In 1962, the market was torn down and relocated to Hunts Point in the Bronx.

This WNYC piece, recorded on the cusp of the market's closing, is a fantastic sonic time capsule of the barkers of broccoli and the callers of cauliflower that considered the market home.

ARCHITECTURE

While the main building that housed Washington Market was torn down in 1962, and the former St. John's Park has been reduced to a dingy plot of pebbles in the middle of a Holland Tunnel exit rotary(described by the AIA Guide to New York City as a "circular wasteland"), there are a remarkable number of intact and preserved buildings dating back over a hundred years.

In the 1970s and 1980s, artists took advantage of the large, open spaces and cheap rent and began to move in, setting up homes and studios in the neighborhood’s former produce warehouses and garment factories. Artists like Richard Serra, Marisol Escobar, Red Grooms, and Laurie Anderson all called Tribeca home and, in a familiar pattern, kickstarted the gentrification trajectory.

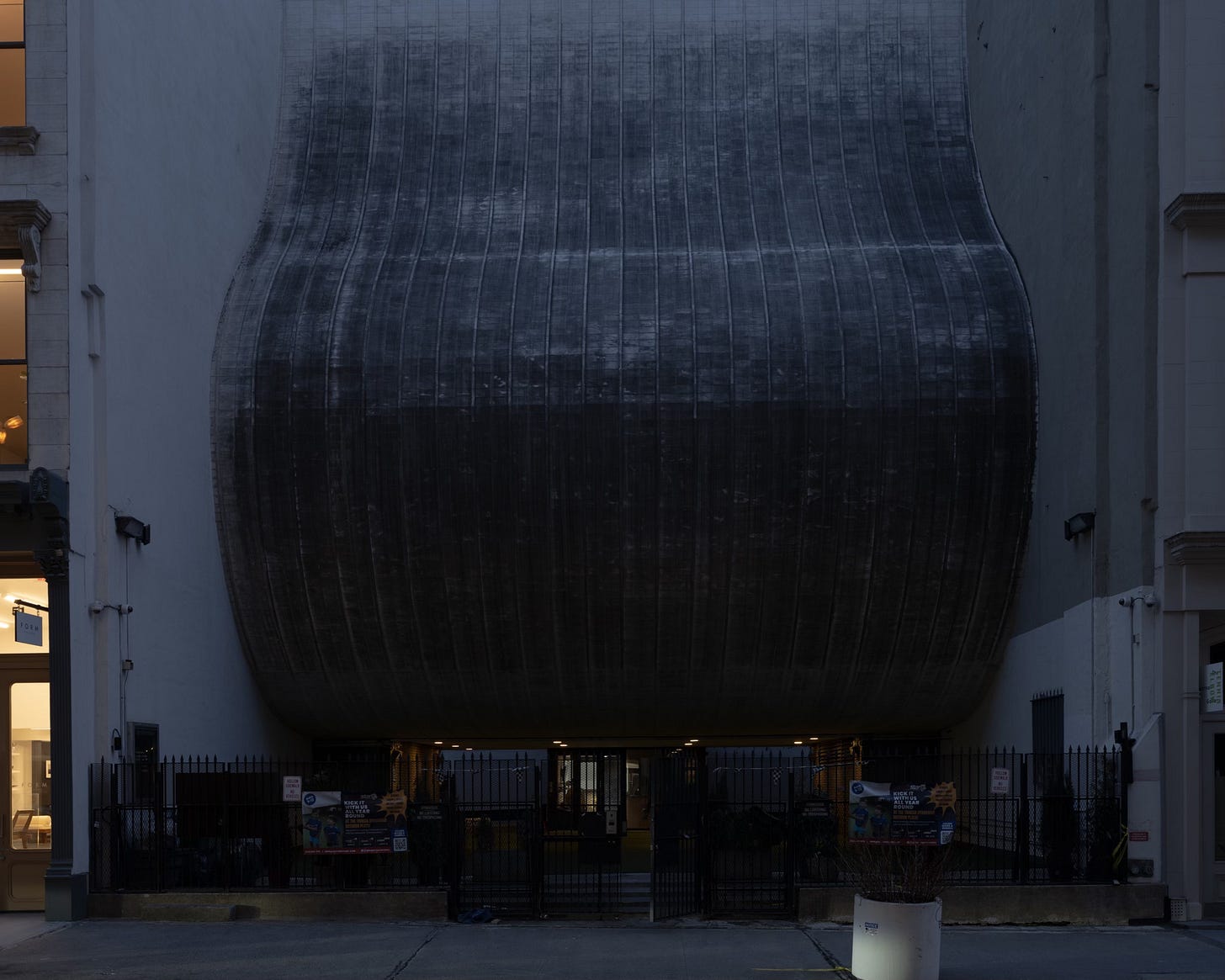

The neighborhood is also home to many architectural marvels of more recent vintage. There is the Tribeca Synagogue, with its undulating marble-clad facade that architect William Breger designed to be able to project voices without amplification on the Sabbath.

A few blocks away is the Herzog & de Meuron-designed 56 Leonard Street, also known as the Jenga Building. Love it or hate it, you can't miss it. The jumble of cantilevered glass and steel cubes rises 821 feet into the sky, making it the tallest building in the neighborhood.

Recently, after several hiccups had left the building beanless, Anish Kapoor's 48-foot by 19-foot sculpted bean of mirror-polished stainless steel, weighing 40 tons, was finally unveiled at the building's base.

At the other end of the aesthetic spectrum is the Brutalist monolith known as the Long Lines building.

LONG LINES

For an anonymous building, 33 Thomas Street, a mute slab of concrete and pink Swedish granite, has quite a reputation. Like 56 Leonard, nobody calls this building by its address. Instead, it's known as the Long Lines Building. Or sometimes, Titanpointe.

With no windows or exterior lights, the skyscraper reads like a void on the skyline, especially at night when the looming monolith blots all light from the buildings behind it.

Architect John Carl Warnecke built the skyscraper to serve as a secure hub for AT&T's long-distance telecommunications network. The 550-foot brutalist bunker was designed to withstand a nuclear blast, and it looks like it.

the design project becomes the search for a 20th-century fortress, with spears and arrows replaced by protons and neutrons laying quiet siege to an army of machines within.

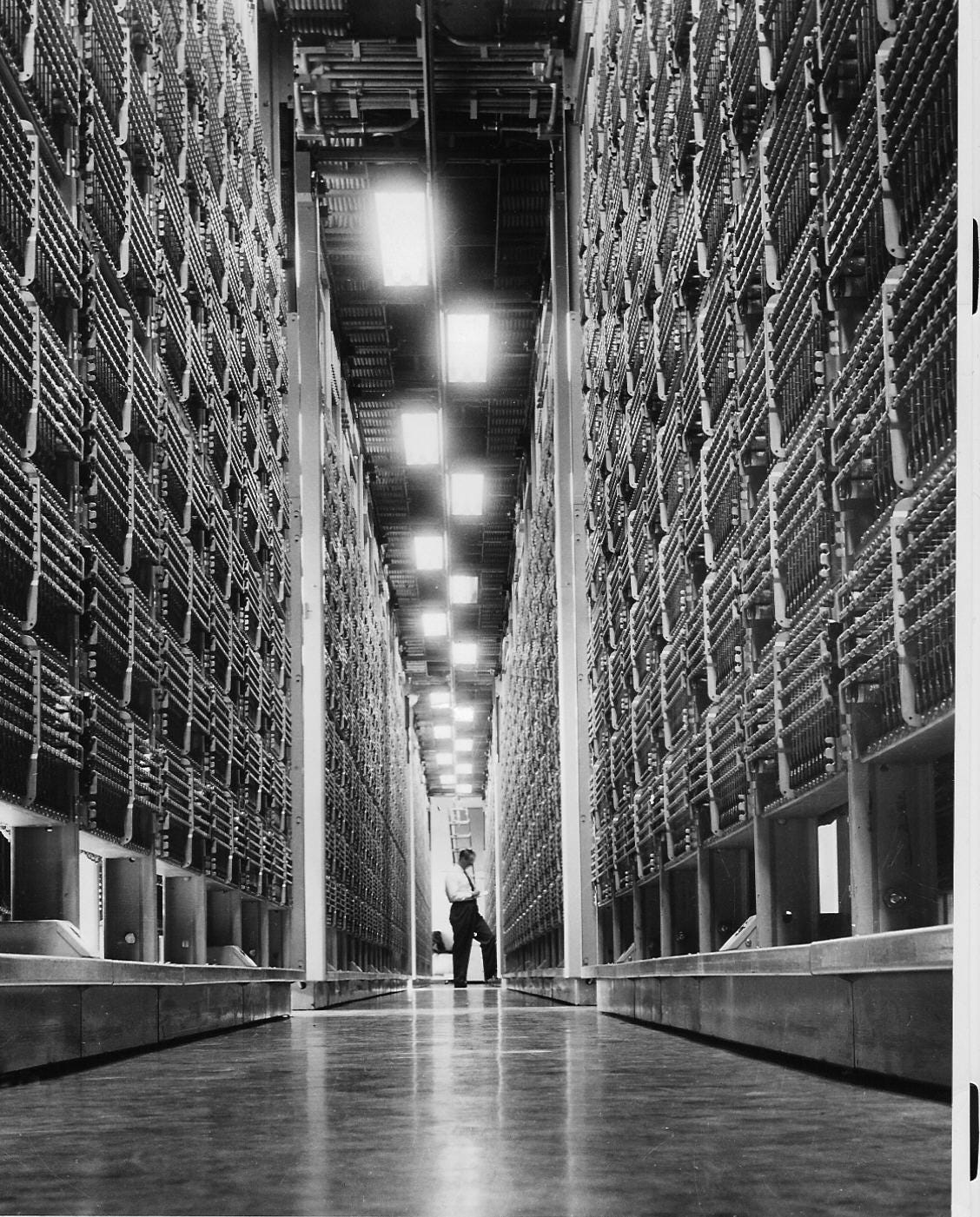

The Long Lines program started as a division of AT&T that implemented and maintained the millions of miles of telephone line that crisscrossed the country in the first half of the 20th century. Those coaxial lines were gradually replaced by a microwave radio system that worked via a system of daisy-chained parabolic dishes. The 29 stories of 33 Thomas were mainly used to house the enormous electromechanical switching machinery that these systems required.

Eventually, with the advent of fiber-optic cables, smaller digital switching systems, and cellular networks, the building was adapted to more modern technologies.

In 2016, based on documents obtained from the Edward Snowden leak, The Intercept determined that the building was functioning as a hub for the National Security Administration.

The Intercept's investigation alleges that the building, codenamed Titanpointe by the NSA, houses gateway switches that route international calls from the United States to countries worldwide. Thanks to a "highly collaborative" relationship with AT&T, the NSA has monitored international long-distance phone calls, faxes, VoIP calls, and other internet traffic. The documents leaked by Snowden documented the NSA's eavesdropping efforts on communications from the UN, the IMF, and the World Bank, all of which likely occurred from within the Long Lines Building.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording weaves the rhythmic clanging of rope and metal on Pier 26 with a sound installation by artist Emmet Palaima droning in the bowels of the Chambers Street Subway.

Arriving subway cars produce a sustained vibration at 224hZ, which Chambers Hum uses as a root note for its tonality. By creating a slowly evolving tonal structure tuned to harmonize with the environmental sounds inherent to the subway system, Chambers Hum restores a connection to the universal order, conveniently located on the Chambers Street A/C Subway Platform.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Here are four photos from Tribeca by German photographer Thomas Struth’s cityscapes project. Part of a larger project, these four photos were taken during a six-month residency at PS1 in 1970.

“I was interested in the possibility of the photographic image revealing the different character or the ‘sound’ of the place. I learned that certain areas of the city have an emblematic character; they express the city’s structure. How can the atmosphere of one place be so different from another, and why? This question has always been important to me. Who has the responsibility for the way a city is? The urban structure is an accretion of so many decisions.”

NOTES

Here is a T Magazine I worked on about Tribeca’s burgeoning gallery scene. New York’s Hottest New Gallery District

For an in-depth look at many of the historical buildings in Tribeca

For all your upright bass needs

Lobel, Cindy R. Urban Appetites. University of Chicago Press, 28 Apr. 2014.

The American Architect (Weekly publication, founded 1876), (New York:243 West 39th Street) (July–December 1920).

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1927/10/01/night-life

Now those Neapolitan smells will run you $42 for a primi... if you can get a table.

Love everything! The stories, the pictures, the young Robert De Niro ancestor/look-alike(?), and “barkers of broccoli and the callers of cauliflower”😄👍