I could think of no better place to mark my 100th neighborhood than Times Square, the compact, incandescent rectangle at the center of Manhattan that much of the world considers the beating heart of the city that never sleeps.

Most New Yorkers feel otherwise. As New York Magazine critic Justin Davidson once put it, Times Square is a “candy-colored hellhole to be avoided whenever possible.” That hasn’t stopped the nearly 330,000 daily visitors who make it arguably the most visited place on Earth.

After all, where else can you pose with a bedraggled Elmo, tuck into a platter of chicken wonton tacos at the world’s largest Applebee’s, or stand shivering for 12 hours just to watch a ball drop, quietly praying your adult diaper holds up?

It’s also home to what some claim is the best slice in the city.

Of course, there’s more to Times Square than enormous jumbotrons, blinking billboards, and the endless parade of chain restaurants. It’s the nexus of the city’s theater district, The Great White Way, which pulled in nearly $2 billion last year. It has also long served as New York’s public square: a place to mark the end of wars, protest injustice, or gather on election night.

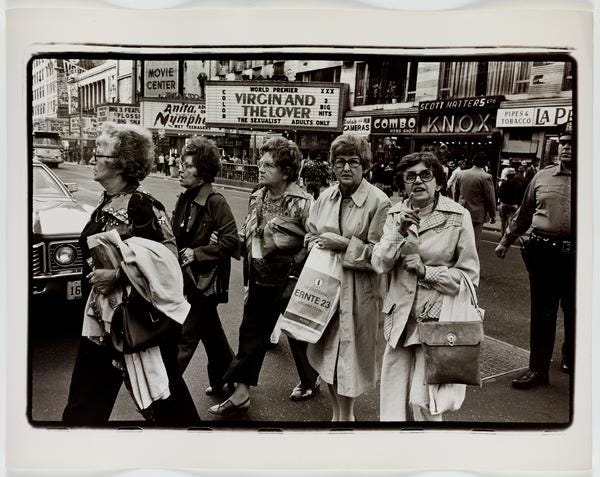

Through its transition from rural outpost to cultural hotspot, to the seedy domain of pickpockets, pimps, and porno theaters, and finally to its latest sanitized iteration, Times Square has remained an accurate barometer of the larger metropolis, what Alan Feuer once called “an urban tissue sample that residents have examined over the years to diagnose the health of their city.”

HORSES TO HEADLINES

In the late 19th century, Times Square was known as Longacre Square, named after London’s Long Acre Street, the center of that city’s carriage trade. Like its namesake, it was where New Yorkers went to test drive a new buggy, get a saddle reflocked, or pick out a fresh horse for their stable.

In 1881, William K. Vanderbilt (New Dorp fame) joined several prominent investors to create “a high-class establishment for commerce in horses.” The result was the American Horse Exchange, built at 50th Street and Broadway.

Disaster struck in 1896, when the entire building burned to the ground in just three hours. Workers managed to open the stable doors, but more than 60 horses died in the flames.

The Exchange was rebuilt and reopened the following year, but the writing was on the wall. Overhead, electric streetcar wires were being strung. Below, subway tunnels were being carved. By 1912, for the first time in city history, automobiles outnumbered horses.

Sensing the shift, Vanderbilt leased the Exchange to the Shubert brothers, who converted it into the Winter Garden Theatre—a venue that would one day be more famous for Cats than carriages.

PUTTING THE TIMES IN TIMES SQUARE

Times Square’s transformation into the city’s cultural epicenter began in earnest a few years earlier, in 1905, when New York Times publisher Adolph S. Ochs chose the neighborhood as the site for his new headquarters.

The plot of land he selected, at the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets, was then occupied by the Pabst Hotel, a nine-story, steel-framed structure featuring a restaurant, a rathskeller (underground bar) and a bachelor’s hotel. It was one of several Pabst-branded establishments across the city, all proudly serving “Blue Ribbon Beer.”

Just three years after opening, the hotel earned the ignominious distinction of being the first building completely supported by a steel skeleton ever demolished.

In its place rose the Times Tower, which briefly became the second-tallest building in the city. With a little prompting from Ochs, Mayor George B. McClellan signed a resolution officially renaming the intersection Times Square.

BALLS

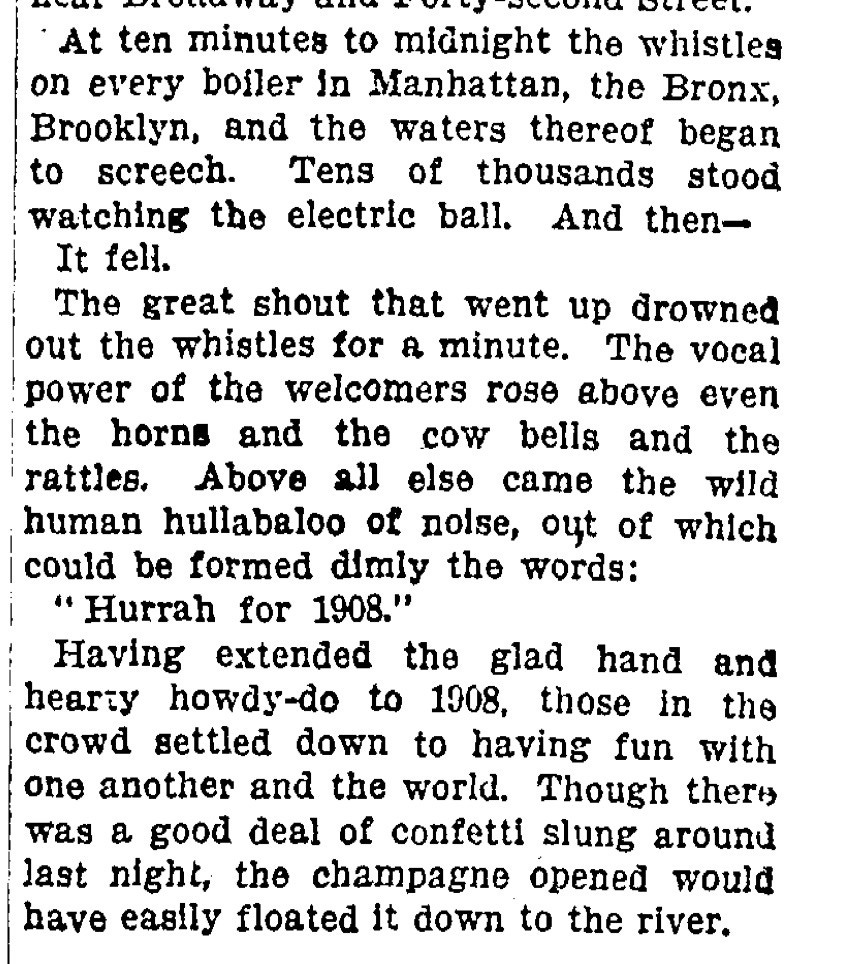

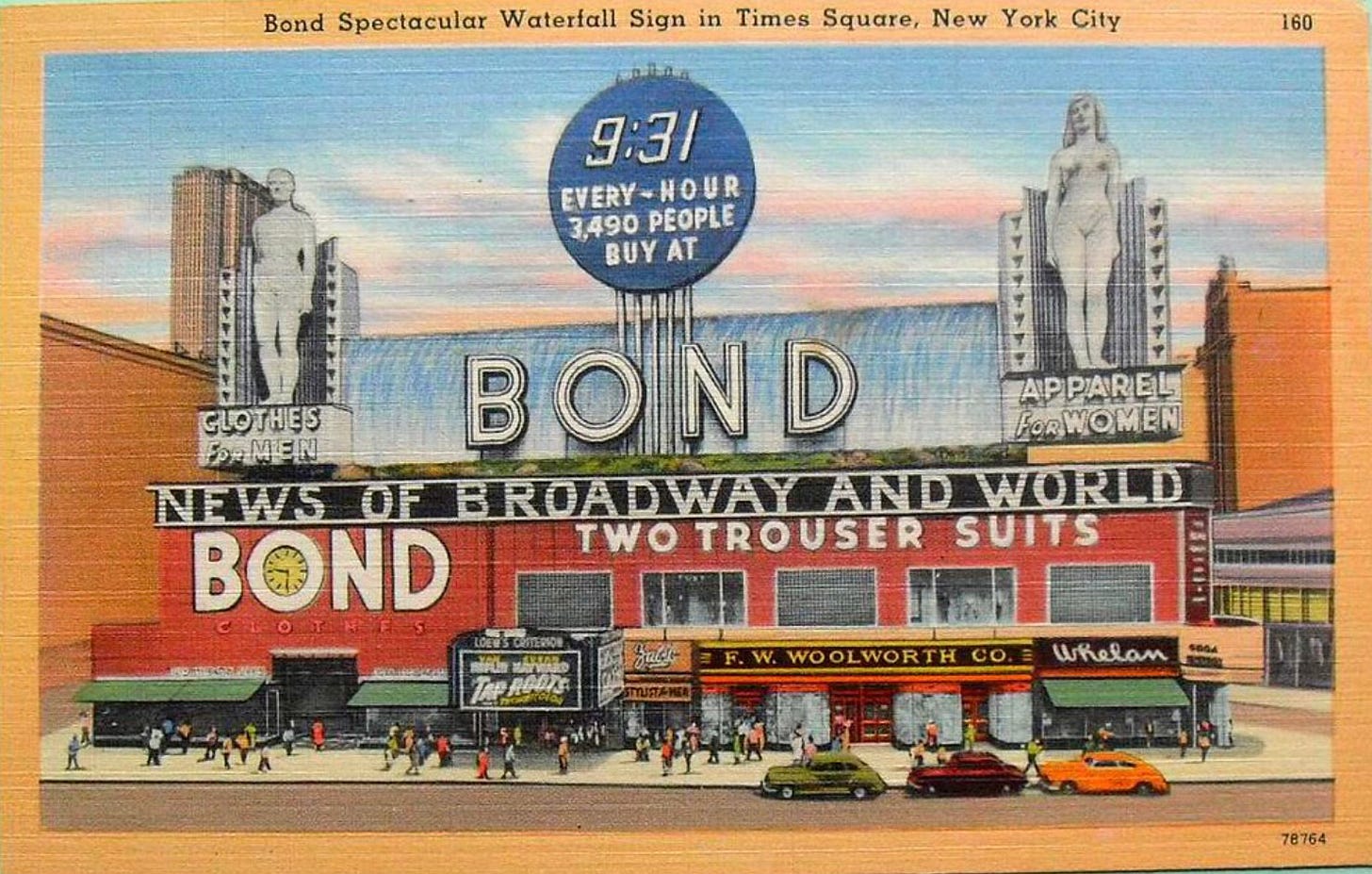

To celebrate the tower’s opening in 1904, Ochs launched fireworks and dynamite from the rooftop on New Year’s Eve. The massive crowds were undeterred by the hot ash raining down on them and soon, Times Square was the place to ring in the new year.

Unsurpisingly, someone at City Hall questioned the wisdom of detonating high-powered explosives in such close proximity to hundreds of thousands of people, and the pyrotechnics were banned. A safer but still crowd-pleasing alternative needed to be found.

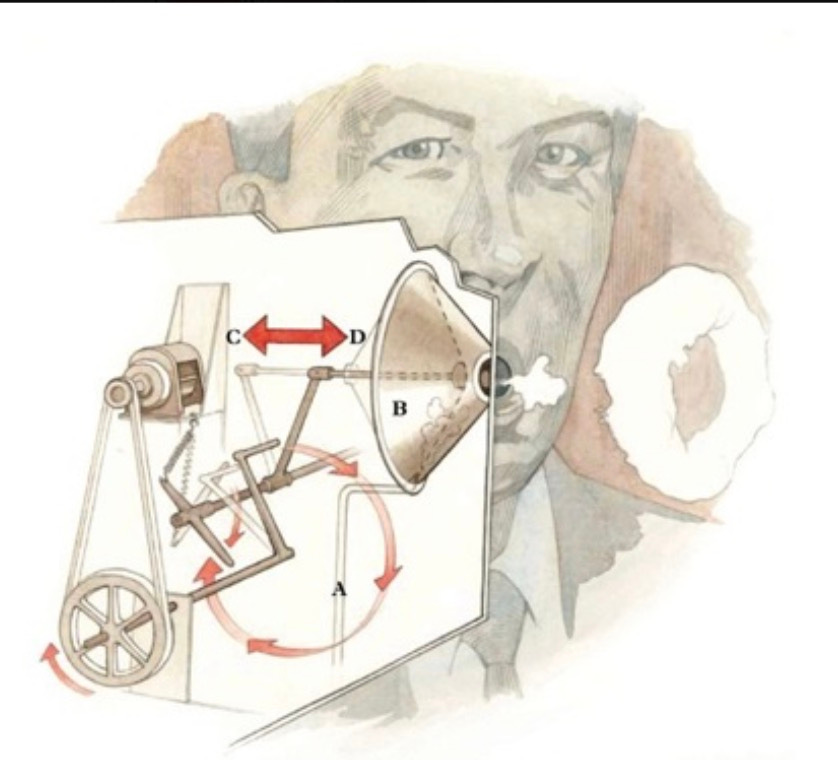

On December 31, 1907, at one minute to midnight, a 700-pound wood and iron ball, lit by one hundred 25-watt bulbs, was lowered from a flagpole atop One Times Square. A new tradition was born.

This pyrotechnic-free way of celebrating the new year was inspired by the early 19th century innovation of time balls, large painted spheres that were mounted on prominent poles and dropped at the exact same time each day. The time balls gave ship captains something to calibrate their chronometers to and provided the public with a way of checking the time in an era before affordable and reliable watches were widely available.

So next time you find yourself freezing in a sea of drunken tourists waiting for the ball to drop, spare a thought—and maybe a howdy-do—for Royal Navy Captain Robert Wauchope, inventor of the time ball.

RED LIGHT / GREAT WHITE

Though Times Square’s descent into sleaze is often associated with the late 1960s, immortalized in films like Midnight Cowboy and Taxi Driver, the neighborhood had been flirting with its seedier side since the beginning.

Back when it was still called Longacre Square, the area marked the northern edge of the Tenderloin, Manhattan’s red-light district. While the city’s elite indulged behind closed doors, a parallel economy of pickpockets, prostitutes, and con artists operated in the margins. It was said that in 1900, you could fire a gun down 42nd Street and hit nothing but sinners.

The opening of the Times Building in 1904 kicked off a theater boom. By 1920, there were 44 new theaters in the area, along with a wave of extravagant restaurants catering to affluent theatergoers—including the Lobster Palaces, lavish temples to a crustacean that had only recently shed its reputation as prison fare.

Next came the movie palaces: The Strand, The Rialto, The Roxy, each one grander than the last, drawing millions to Times Square and cementing its reputation as the city’s entertainment capital.

But the exuberance couldn’t outlast the Great Depression. As economic hardship set in, legitimate theaters pivoted to movies or burlesque, while some of the movie houses began screening lurid “grindhouse” fare. The honky-tonks, flea circuses, nickelodeons, and brothels that once lurked in the shadows stepped into the neon glare.

LIGHT SHOW

The man responsible for much of that artificial light, Douglas Leigh, could be considered Times Square’s patron saint.

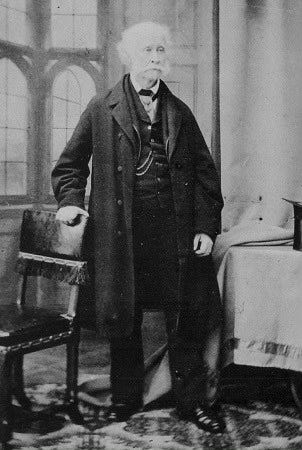

Leigh was the mastermind behind many of Times Square’s most iconic electrified billboards, known as “spectaculars.” These massive, animated displays became as essential to the area’s identity as the Broadway theaters and movie palaces whose facades they adorned.

The 200-foot-wide, 50-foot-high billboard above Bond Clothiers was on of Leigh’s most memorable creations. The two giant nude statues flanking a cascading waterfall at the billboard's center were magically "clothed" when electric lights illuminated them at night. In later years, the figures were replaced by Pepsi bottles and oversized packs of Camel cigarettes

Mandated light restrictions during WWII threatened the entire spectacular industry. In response, Leigh designed perhaps his most iconic creation, a billboard for Camel featuring a rotating cast of smokers (soldiers, actors, doctors) who appeared to blow out four-foot-high steam “smoke rings” every few seconds, no electric lights required.

Leigh even briefly owned One Times Square itself, purchasing it from The New York Times in 1961. He stripped away the marble facade, reimagining the iconic building solely as a blank canvas for his creations.

FALL AND RISE

The cracks that appeared during the Depression never fully healed. Despite sporadic efforts to clean it up, Times Square’s decline only accelerated over the following decades. By the early 1970s, with the city on the brink of bankruptcy, Times Square had come to symbolize everything that was wrong with New York City. Rolling Stone deemed 42nd Street, nicknamed The Deuce, the "sleaziest block in America." Sex shops, massage parlors, porn theaters and peep shows made up the bulk of its businesses.

The streets were crowded with junkies, hustlers and runaways. Amazingly, tourists still attended Broadway shows, though the drama on the streets undoubtedly eclipsed anything in the theater.

Over the years, several mayors attempted to halt or reverse the neighborhood's decline. Fiorello LaGuardia raided 2,000 pinball machines, denouncing the “slimy crews of tinhorns, well-dressed and living in luxury on penny thievery.” Robert F. Wagner cracked down on “open-door nuisance establishments” like wax museums, freak shows, and shooting galleries.

Though the mayor most associated with the neighborhood's turnaround is Rudy Giuliani, it was Ed Koch who started the process, using eminent domain to condemn and take control of several decrepit theaters and erecting in their place the 50-story, 2,000-room Marriott Marquis, the "opening salvo in a war to remake Times Square."1

Then, in 1993, David Dinkins got Michael Eisner to invest in renovating the New Amsterdam Theater, paving the way for the eventual wholesale Disneyfication of Times Square.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

Today's audio, like this week's newsletter, runs a little long and, for the neighborhood, is appropriately chaotic. The recording features a post-theater field trip, a confrontation at an anti-Dominican Republic protest, several unsuccessful attempts to drum up business for a comedy club, and the official songbird of Times Square, a small man whose high-pitched mantra of "fuck yous" shocked and delighted the passing crowds.

At the end, if you make it that far, you can barely make out the hum from Max Neuhaus' subterranean sound installation, hidden under a grate covering a steam vent, one of my favorite things in Times Square that is virtually impossible to make out over the siren-punctuated soundtrack of the city.

In Times Square, everyone is a photographer.

Smartphones have largely replaced the smaller point-and-shoot cameras that were once a mainstay of any tourist's fanny pack.

There are wedding photographers. Event photographers. Open-air photo booths that feature a large protruding arm holding a phone recording tourists spinning like a cylinder of gyro meat while awkwardly dancing to a never-ending loop of Alicia Keys's "Empire State of Mind."

There are roving bands of camera-toting photographers with iPads strapped to their chests, like ammunition belts, taking pictures of people wandering around the square, who are often taking pictures themselves. Inverting the usual paparazzi paradigm, these surreptitious snappers then try to sell the photos to their unwitting subjects.

There are cameras in every lamppost, on every building corner, and in every pocket and dashboard. Add to that the expansive archive of street and architectural photography created by some of history’s most acclaimed photographers, and Times Square becomes perhaps the most thoroughly documented place on earth

As I wandered the streets of Times Square last week, the one question I kept asking myself (besides when was the last time that Elmo suit saw a washing machine) was what can I add to all this?

Not much, but I had fun trying.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I have been a fan of Andrew Moore's work ever since I came across his photobook Russia: Beyond Utopia, a collection of meticulously composed landscapes, interiors, and environmental portraits in post-Soviet Russia, captured with a large-format camera and marked by his masterful use of color. Andrew has published several other monographs, including Detroit Disassembled and Dirt Meridian, and his photographs are held in numerous public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

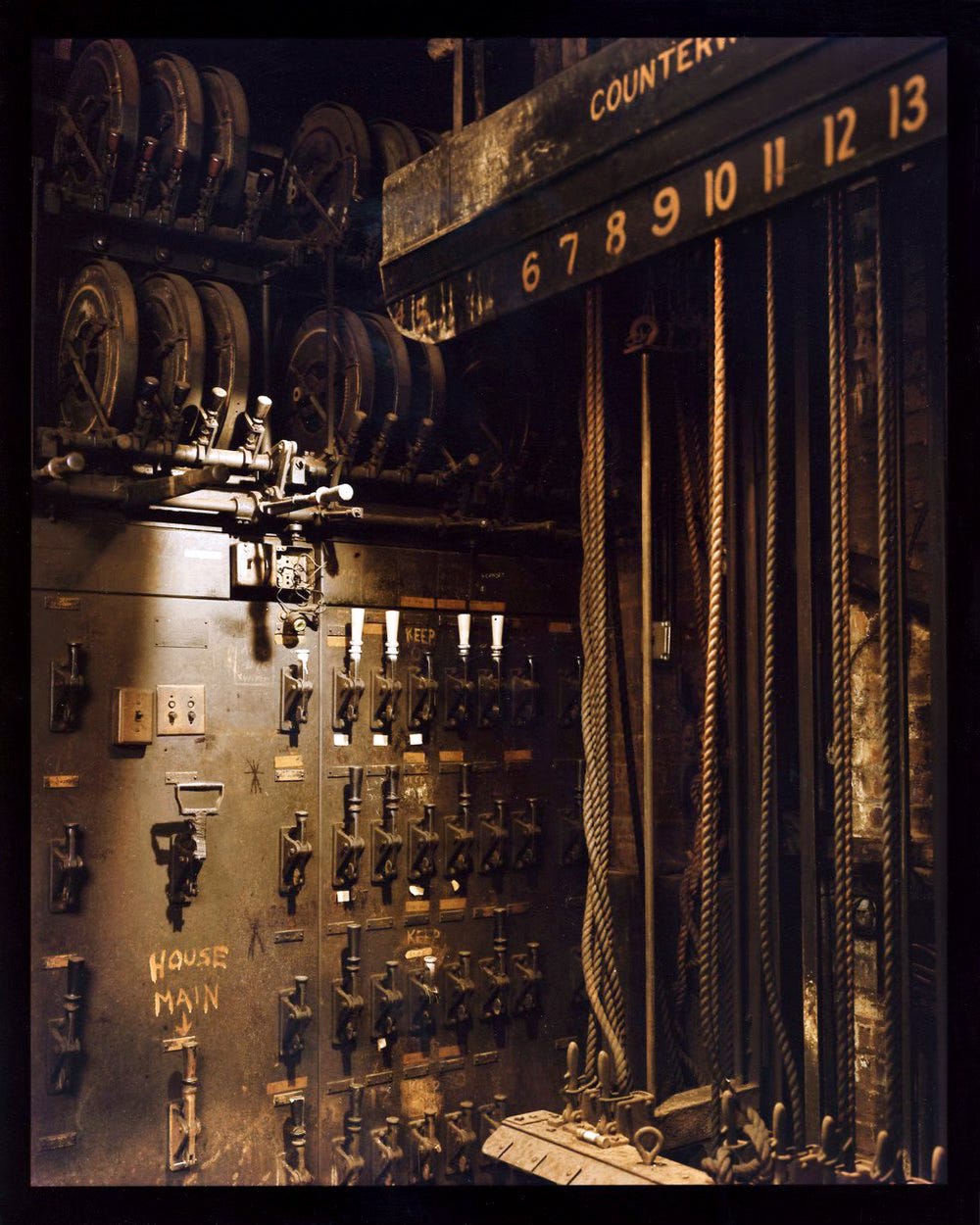

Andrew was kind enough to share a selection of his images documenting the interiors of several of 42nd Street's historic theaters, taken just before their demolition or renovation. In his words:

One day while leaving the IRT at the corner of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue, I noticed how the renovation of the New Victory Theater had added the original projecting entrance stair from the days of David Belasco. My interest was piqued by this nostalgic reconstruction, and through some city contacts, I met with Cora Cahan of The New 42nd Street, Inc. After I explained my interest in photographing the theaters, particularly the interiors, she kindly allowed me to access the buildings during a six-month period in 1995-96. Of the nine theaters along 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, two were undergoing preservation and renovation, while the rest remained as empty shells, some utterly stripped, the others in fair condition at best. I’ve always enjoyed the barrenness of gigantic skeletal remains. At the conclusion of my work, I felt certain that whatever fate these structures had suffered was merely temporary, and that an appropriately ostentatious rebirth awaited them. I with look forward, with great trepidation, to the continuation of this story along 42nd Street

This is why I put the featured photograpy after my own! To see more of Andrew’s work, you can visit his website, Andrewlmoore.com.

NOTES

There are still a few days left to catch the Richard Sandler retrospective at Anthology Film Archives in the East Village. The series includes a screening of The Gods of Times Square, ”a rough-and-tumble document of a rapidly changing Times Square and of the incredible collection of eccentrics, street preachers, panhandlers, entertainers, and other charismatic city dwellers who comprised the rich human comedy of the neighborhood at the time.”

Other films in the program include Subway to the Former East Village and The Gods of Times SquareD, a follow-up to the original that screens on the 11th—the closing night of the retrospective.

The Times Square ball drop has spawned countless imitators. Take, for example, the town of Tallapoosa, Georgia, where a stuffed opossum named Spencer is lowered to mark the New Year. Or Carlisle, Pennsylvania, which marks the occasion by dropping a chili cheese dog. In 2011, Snooki, from the MTV reality series Jersey Shore, was lowered inside a "hamster ball,” which sounds festive. One of the most intriguing ceremonies takes place in Mount Olive, North Carolina, where the Mt. Olive Pickle Company celebrates by dropping a three-foot pickle down a flagpole into a pickle tank. As an added bonus, the pickle drop is observed at 7PM making it instantly my favorite New Years’s celebration.

If you’re not in the mood for a Blooming Onion or a Forrest Gump Seafood tower, there is an oupost of my favorite spot for a healthyish meal in the city on 43rd st. Not as incredible as the OG, but still a good option. Green Symphony.

In other news, Actual Place, a record I made with my friend and collaborator Aaron Fisher, comes out today. This is the second record we have made together, and, for those of you who are into “ a warm and gentle psychedelic mix of Talk Talk, Tortoise, and ambient country exponents SUSS,” maybe you’ll find something you like here. It’s available on all the major streaming services like Apple Music, Spotify and Bandcamp

https://ny.curbed.com/2017/3/9/14833004/broadway-theaters-closed-times-square-history

Revive the American Horse Exchange!

I have memories of Times Square from 1981 when I was a clueless teenager. I was used to London but this was another level of dirty, smelly and sleazy. So, of course, I loved it. Congrats on this milestone edition and on the release of your album.