I’m hard-pressed to think of a better neighborhood name than Spuyten Duyvil (spai·tuhn dai·vl), the small community bisected by the Henry Hudson Parkway in the northwestern corner of the Bronx. The general consensus is that the name is a derivation of the Dutch Spuitende Duivel, meaning spouting (or spitting) devil, an allusion to the once treacherous currents of the local creek. Historian and party pooper Reginald Pelham Bolton claimed the name had nothing to do with the devil at all and meant “spouting meadow,” a reference to a spring in nearby Inwood.

IN SPITE OF THE DEVIL

There is also a small but vocal contingent of armchair etymologists who think the neighborhood’s name means “in spite of the devil,” thanks to Washington Irving’s 1809 A Knickerbocker's History of New York.

Irving tells the story of trumpeter Anthony Van Corlaer who, in 1669, was tasked by Peter Stuyvesant with warning settlers along the Hudson of an impending British invasion. The corpulent Corlaer, whose enormous, copper-colored nose had earned “the wonder and admiration of all who knew it,”1 sprung into action.

When Van Corlaer got to the tip of Manhattan, he was determined to swim across the swiftly moving river and “swore with ornate and voluminous oaths” that he would cross the water “in spite of the devil.” That turned out to be a bad decision as Anthony, his nose, and his trumpet were soon pulled under. It is said that under the right conditions, the “shrill of his trumpet” can still be heard near the creek. While it’s a good story, Irving’s History of New York was a parody, so Corlaer’s cry is probably not the origin of the name.

HENRY HUDSON BRIDGE

Today, Van Corlaer could make it across Spuyten Duyvil Creek without much effort at all. The Harlem River Ship Canal, which was completed in 1923, widened and straightened the waterway, taming the currents that sucked poor Anthony under. He could also just walk across the Henry Hudson Bridge, the 800-foot-long, 143-foot-high steel arch connecting Manhattan to the Bronx built by Robert Moses.

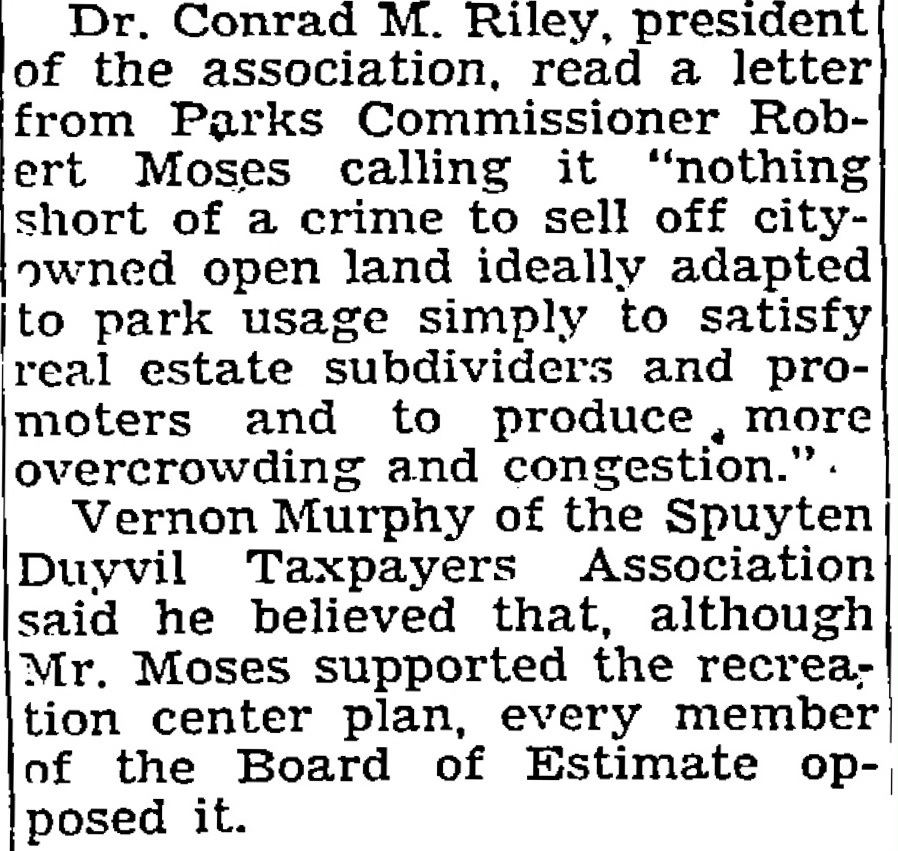

Despite local opposition, the bridge cut right through the city’s last stand of virgin old-growth forest in Inwood Park and divided what was then the sleepy village of Spuyten Duyvil in two.

There were more obvious, far less disruptive locations for the bridge, but Moses, the embodiment of the end justifies the means ethos, had figured out that if he built his highway through the park, he could get the federal government to help pay for it. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) was a New Deal program that created manual labor jobs for millions of unemployed workers during the Depression. While the CWA wasn’t interested in building highways, they were more than happy to provide labor for “park access roads,” so Moses rebranded his six-lane, 140-foot-wide highway and ran it right through the middle of the park.

Before the bridge was built, city reformers accused Moses of “treating city parks as if they were his own private property” and demanded a public hearing. Moses agreed. In the two weeks leading up to the meeting, in classic Moses fashion, he had his crew cut down hundreds of trees for the bridge’s right of way, effectively gutting the whole unspoiled wilderness argument.

The bridge was completed in 1936.

TRAIN WRECK

54 years earlier, on a snowy January evening in 1882, a southbound New York Central passenger train collided with a train stopped on the tracks outside Spuyten Duyvil. Eight people were killed, and 19 were seriously injured.

The stopped train, on the last leg of its journey from Chicago, was full of politicians who had recently boarded in Albany after the State Legislature had let out for the weekend. The influx of new passengers necessitated an additional 15 cars and a steam locomotive. Like our friend Anthony Van Corlaer, who demonstrated an “assiduous devotion to keg and flagon,” the politicians were soon taking full advantage of the generously stocked bar car.

According to the train’s conductor, one of those revelers, whose identity was never disclosed, decided it would be good fun to pull the brake, bringing the Chicago Express to a screeching halt.

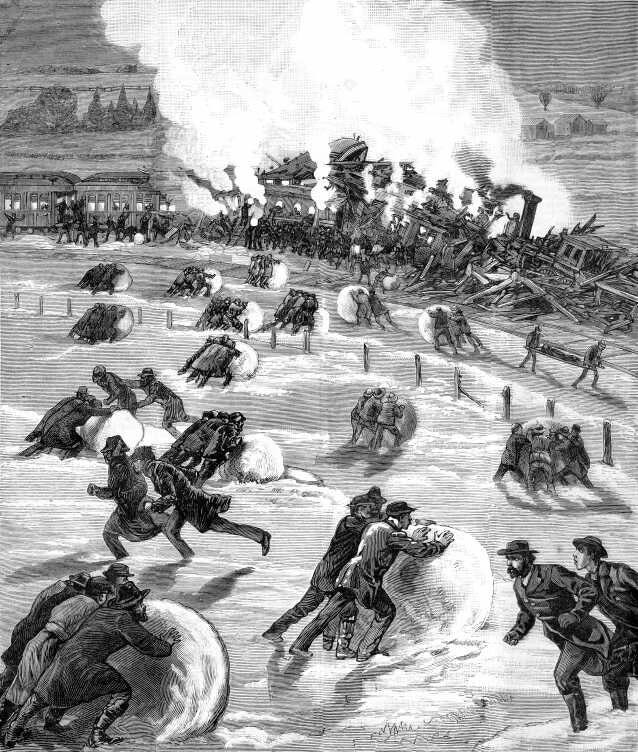

A few minutes later, just after 7 PM, the Tarrytown Special ran full speed into the back of the stalled train, “telescoping” the rear two passenger cars into one another. One of the train’s stoves tipped over, starting a fire, and the passengers, trapped in a jumble of timbers and broken glass, began to be “slowly roasted alive.”

In the absence of even the most basic fire-fighting equipment, onlookers and other passengers started rolling giant snowballs to throw onto the burning cars to extinguish the flames.

Among the dead was Senator Webster Wagner, the founder of the Wagner Palace Car Company and inventor of the luxurious parlor train cars that he was found crushed between. The senator’s body was so severely burned that the only way to identify him was through a gold watch bearing his initials, “W.W.”

After an investigation, the Hudson River Railroad Company and its employees, including conductor George Hanford and brakeman George Melius, who was accused of insufficiently warning the oncoming train, were found negligent. Though the drunken brake puller’s prank didn’t factor into the verdict, plenty of people blamed the accident on his actions.

On the morning of December 1, 2013, a Metro-North Railroad Hudson Line passenger train derailed near the Spuyten Duyvil station, killing four passengers and injuring 61 more. The train had gone into the notoriously dangerous Spuyten Duyvil curve at almost three times the posted speed limit. The train’s engineer, William Rockefeller, said that he had gone into a “daze” moments before reaching the curve, a condition that was later linked to extreme sleep apnea.

THE CITY UGLY

You can find one of the most unique apartment co-op complexes in the entire city in Spuyten Duyvil. The Villa Charlotte Brontë, perched one hundred feet above the spot where the Harlem River meets the Hudson, is what Christopher Gray describes as “a fantasy sand castle for the Amalfi coast designed by M. C. Escher.” 2 The complex’s 17 apartments feature terracotta tiled roofs, casement windows, and wisteria-covered walls and are connected by a series of staircases, walkways, and stone arches.

Architect Robert W. Gardner was hired to design the buildings by John J. McKelvey, a key figure in shaping Spuyten Duyvil’s landscape. As one of the trustees of Park District Protective League, McKelvey fought against what he called the “city ugly,” establishing Spuyten Duyvil as a refuge from the encroachment of Manhattan’s tenement apartment buildings. He bought up land in the neighborhood and built several apartment complexes, including the Villa Victoria, the Villa Brontë, and the recently demolished Villa Rosa Bonheur.

Curbed published a great piece on Villa Brontë a few years ago.

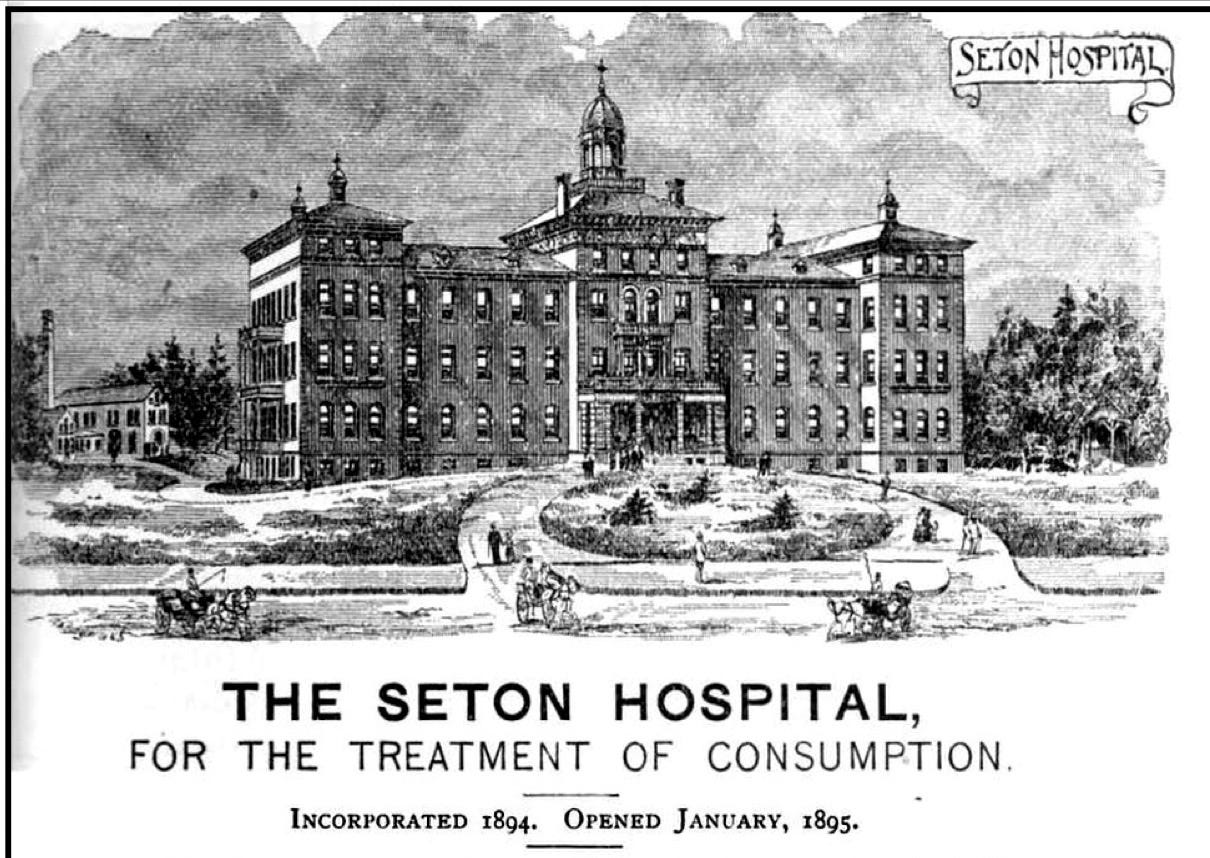

One of McKelvey’s earliest causes involved a call to relocate Seton Hospital, the Roman Catholic home for Consumptives, out of the neighborhood. McKelvey and his neighbors claimed that the hospital’s inhabitants spent all day wandering around the neighborhood, “disregarding all sanitary rules with respect to expectoration.”

Despite it being a fitting homage to the neighborhood’s name, Spuyten Duyvilians were not amused by the patients’ penchant for hocking loogies. The city bought Seton Hospital and demolished it in 1956. The only evidence of the hospital’s existence is an abandoned grotto erected in memory of Mother Seton, tucked in a thicket of woods behind some tennis courts in Seton Park.

Incidentally, it was Robert Moses who pushed for the old hospital’s conversion to a park.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

In the introduction to this week’s newsletter, I mentioned the legend of Anthony Van Corlaer and how, if the conditions were just so, you could hear the siren call of his horn. Well, imagine my surprise when I was walking through Sputen Duyvil the other day and was suddenly assailed by several piercing trumpet blasts. They stopped for a minute before starting anew. Could this be the ghost of Van Corlaer, I wondered?

The dissonant trumpet peals eventually led me to Spuyten Duyvil playground, though it took me a few minutes to pinpoint their source. Then, finally, I found him. It was not the red-nosed Corlaer, but rather, an older gentleman who had cordoned off a corner of the park with yellow caution tape and was attempting to play along with a recording of KC and the Sunshine’s band 1976 disco smash hit, Shake Shake Shake, Shake Your Booty. It was a very loose interpretation.

This week’s field recording features the ghost of Corlaer and the Sunshine Band, plus some action along the train tracks, a raucous kickball game, and, for good measure, someone listening to a positive affirmation audiobook.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

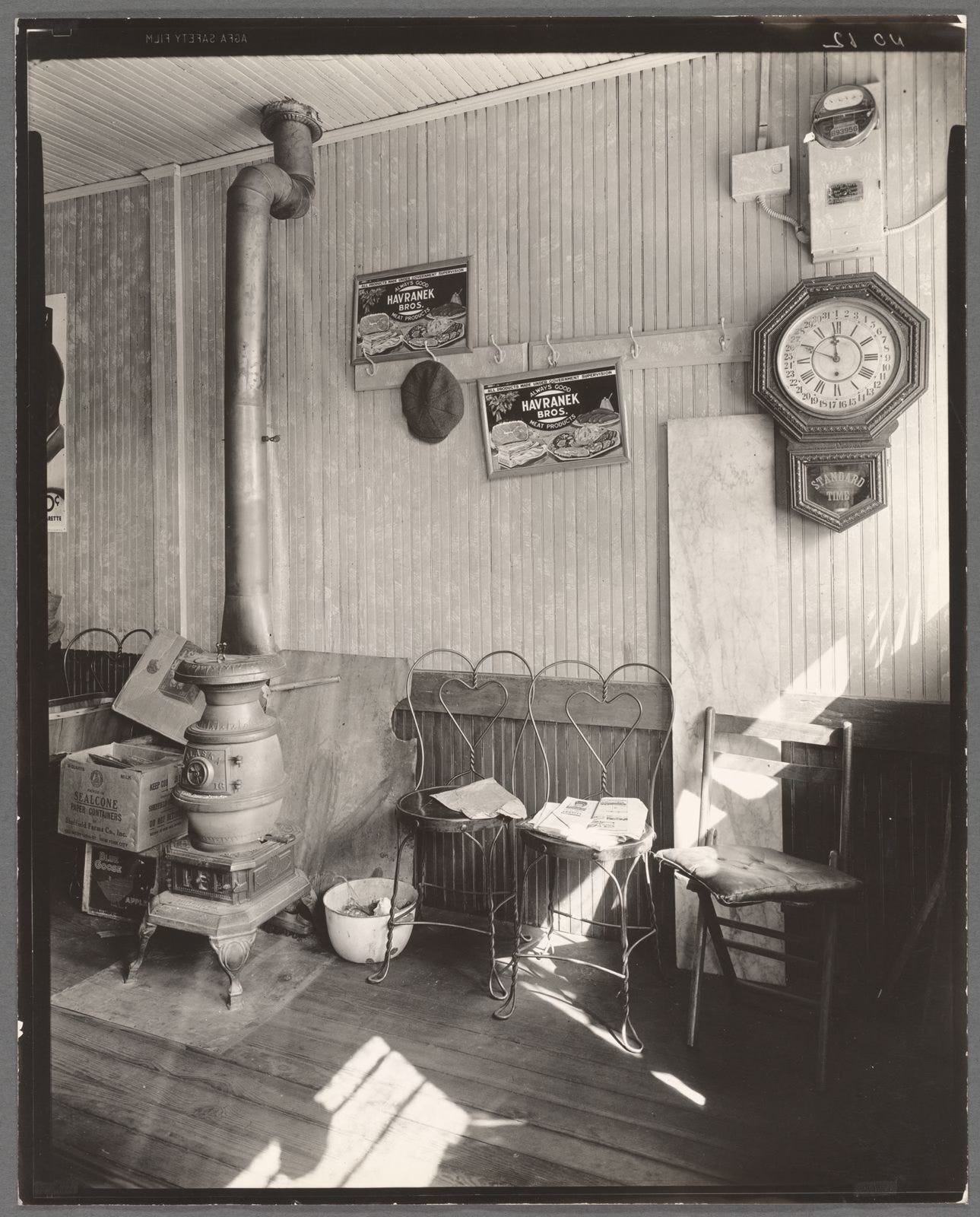

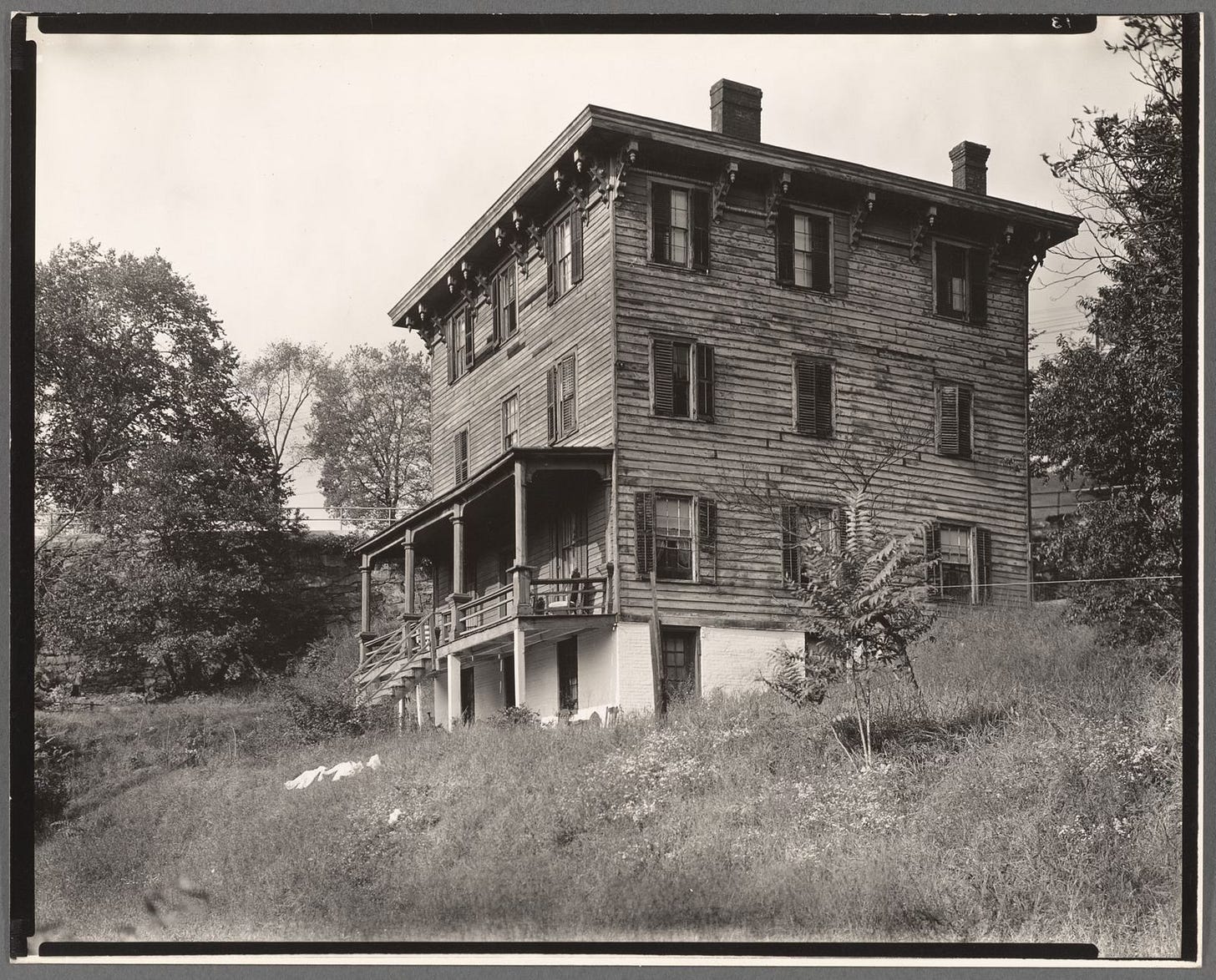

The same year Robert Moses was taking advantage of CWA funded labor to finish the Henry Hudson Bridge, Berenice Abbott was working on her Changing New York project with support from the Federal Art Project (FAP). Another New Deal program, the FAP, created jobs for unemployed artists. These three wonderful photographs were taken by Berenice Abbott in Spuyten Duyvil in 1935.

ODDS AND END

When Senator Wagner died between his train cars, he joined a select list of inventors killed by their own inventions. Take, for example, William Bullock, who had his foot crushed in his rotary printing press and died during the foot’s amputation. Or Henry Winstanley, who designed and built the world's first offshore lighthouse in Devon, England. He was eager to demonstrate just how safe his invention was by sheltering in it during the Great Storm of 1703. The lighthouse was completely destroyed, and Winstanley was never seen again. Then there was Thomas Midgley Jr., an engineer who contracted polio at age 51, leaving him severely disabled. He invented a rope and pulley system to help lift him out of bed. A few years later, he got caught in the ropes and was strangled to death by his own invention.

While Jimi Heselden, the owner of Segway Scooters who died when his Segway plunged off a cliff, is often included on the list, it was Dean Kamen, who sold the company to Heselden one year prior to the accident, who invented the motorized scooter.

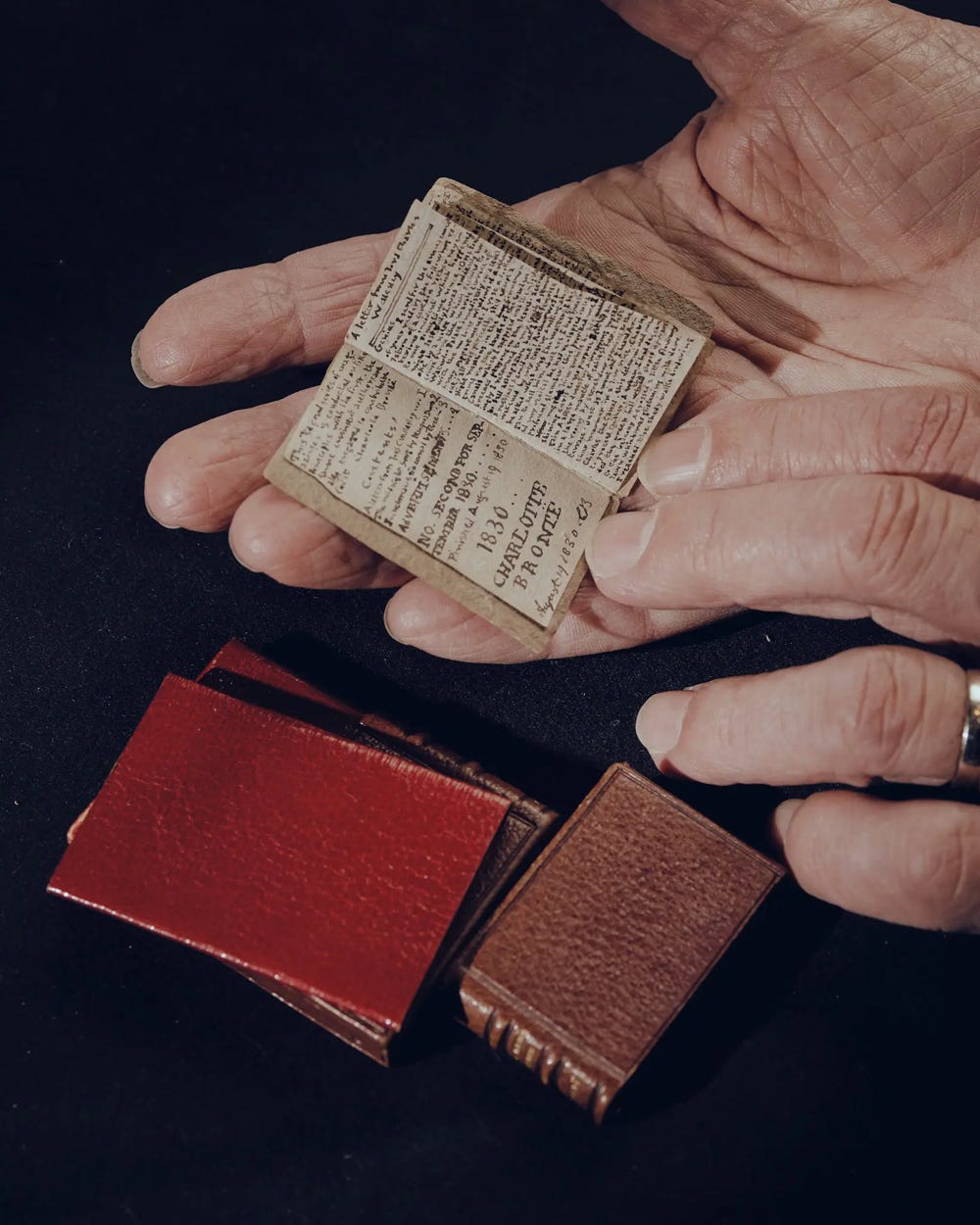

When researching the Villa Charlotte Brontë, I came across an image of one of Brontë’s miniature journals, written when she was fourteen.

While the ability to write this small is amazing, it is nowhere near as amazing as the story of the journal’s owner, Gérard Lhéritier, aka the Bernie Madoff of France. Instead of trading in securities, Lhéritier traded in rare books and letters, offering investors shares in correspondences from Einstein and Mark Twain and first-edition Flauberts while making impossible promises to buy back any investments with interest. Just as the walls were closing in on Lhéritier and his lavish antiquarian book lifestyle, he won the largest ever EuroMillions jackpot, worth €170 million. You can read the whole story here: A Billion-Dollar Scandal Turns the ‘King of Manuscripts’ Into the ‘Madoff of France’.

Just last month, Spuyten Duyvil, the craft beer mecca that opened in Williamsburg 21 years ago, served its last pint.

"The Last Blast of Anthony the Trumpeter" is a piece by composer Kamala Sankaram about Van Corlaer’s fateful journey across the Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6615/6615-h/6615-h.htm

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/22/realestate/22scap.html?_r=0

The more of your articles I read, the more I enjoy how different each of the neighborhoods are.

The snowball etching!