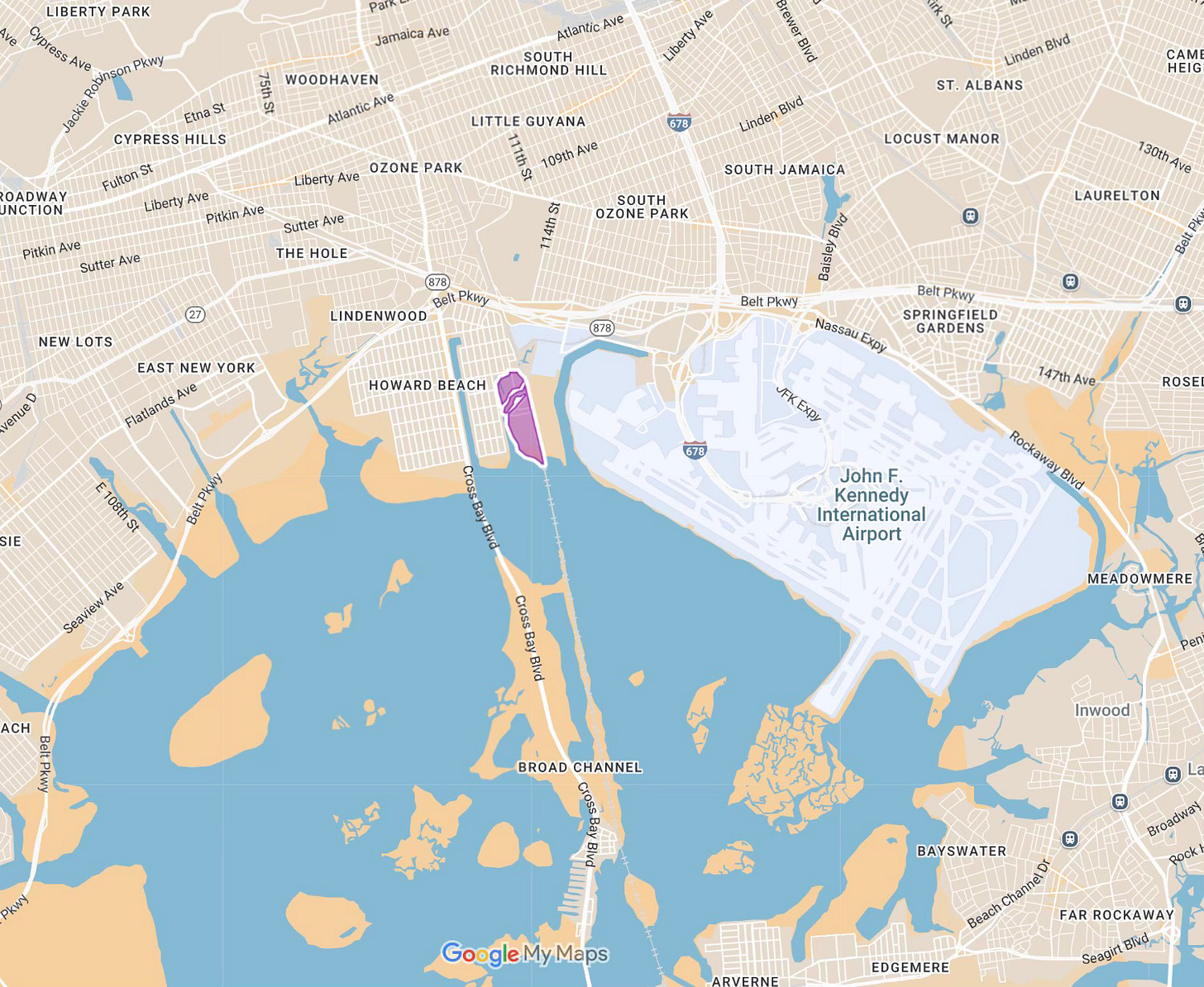

About a year ago, I visited the diminutive Queens neighborhoods of Meadowmere and Warnerville. At the time, I noted that, even when combined, the two felt like the smallest neighborhood in the city. This week, I visited the Queens neighborhood of Ramblersville, situated just on the other side of JFK Airport from Meadowmere, which many people consider the city’s official smallest neighborhood. “Official” is doing some heavy lifting here, as there really is no such thing as an official neighborhood designation in New York City—only a loosely agreed-upon, often contested, and ever-changing web of invisible borders (see An Extremely Detailed Map of New York City Neighborhoods).

This “official” designation seems to come from a 2016 Curbed article that, after analyzing StreetEasy data, identified Ramblersville as having the least real estate per square foot in the city, making it the smallest neighborhood. While I’m not entirely sure what that means, a walk through the neighborhood, where the boats outnumber the people, seems to confirm their conclusion.

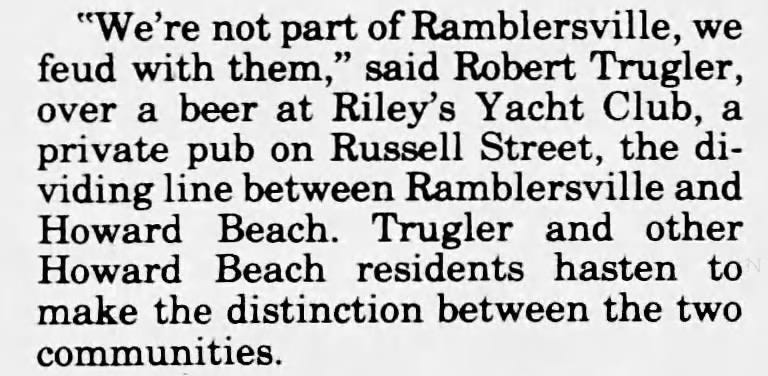

Ramblersville is often grouped with Hamilton Beach, which, in turn, is sometimes considered part of the larger Howard Beach area. However, Ramblersville predates them both, having been established long before goatskin glove magnate William Howard developed the neighborhood that now bears his name.

For this week’s newsletter, I’m focusing on both Ramblersville and Hamilton Beach, situated between Hawtree Creek and the tracks of the Rockaway Line. Much like Meadowmere and Warnerville, they share a similar history and landscape, even if some locals aren’t keen on the affiliation.

THE VENICE OF NEW YORK

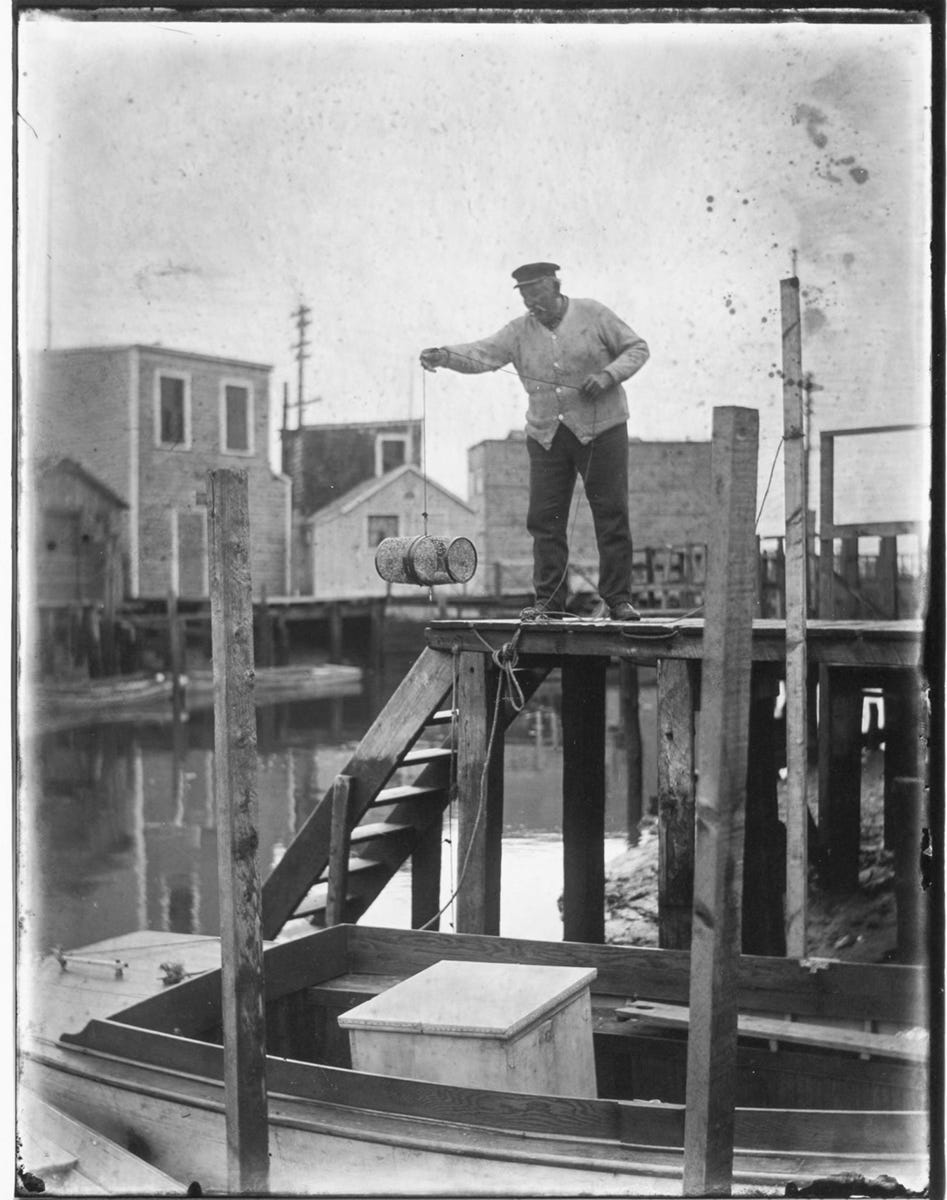

Construction of the five-mile wooden trestle across Jamaica Bay, connecting the Rockaways to the rest of Queens in 1880, instantly made the edges of the great tidal estuary more accessible to the citizens of New York City. Already home to a small cluster of fishing huts, Ramblersville quickly began to attract a modest summer population. By 1902, the area had earned the name "the Venice of New York," with its charms extolled in prominent publications such as the Brooklyn Daily Times and the Brooklyn Eagle.

The articles describe an almost utopian paradise where the men spent their days clamming or spearing eels, while the women, with the "flush of health on their cheeks," would glide around the small creeks on their boats, making early morning social calls "which are fashionable only in unfashionable Ramblersville."

When the tide came in, the brackish waters of Jamaica Bay would flow beneath the ramshackle conglomeration of fishing shacks perched on stilts above the seagrass. A network of narrow boardwalks wended through and above the marsh. Clubs with names like the Fraternals from Bushwick, the Jolly Boys, and the Cherry Pickers from the twenty-first ward had buildings along the creek.

Remarkably, despite being entirely surrounded by water, there was never a single drowning reported in the early years of Ramblersville's existence. There was no crime to speak of ("a policeman is looked upon as a foreigner") and no sickness either. The only doctors in Ramblersville were there to work on their tans.

According to a 1902 report, the greatest problem faced by the residents had nothing to do with crime or health but rather a peculiar quirk in the design of the bridge that spanned Hawtree Creek. According to the story, "several fat ladies have been known to be caught between the post and the rail and held there until extricated." There was a genuine concern that the bridge's design might discourage "prospective fat settlers, who are regarded as desirable." The bridge was built by Oscar Rust, often credited as the founder of Ramblersville. Ironically, Rust may have been the person most affected by his own design's unintended corpulent gatekeeping, as he owned and operated the town's only hotel.

The idyllic lifestyle led by Ramblersville’s presumably skinny residents faced its first serious challenge in 1916 when, for the first time, the Board of Health banned fishing and swimming in Jamaica Bay due to pollution, an issue that would plague the shoreline for generations. Hamilton Beach residents relied on private septic systems through the 1960s and 1970s and weren’t connected to the municipal sewer system until 1995. Ramblersville had to wait until the early 2000s.

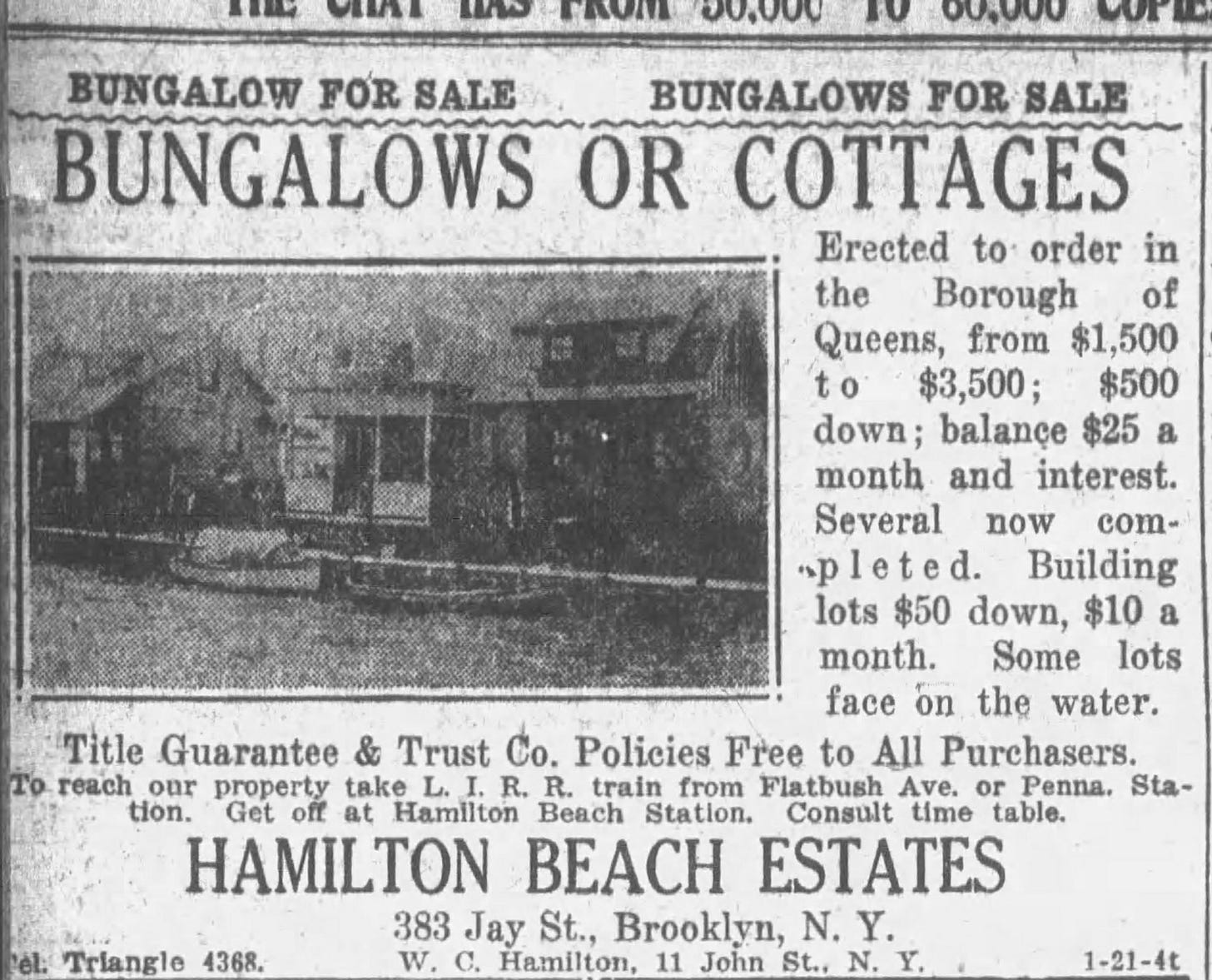

HAMILTON BEACH ESTATES

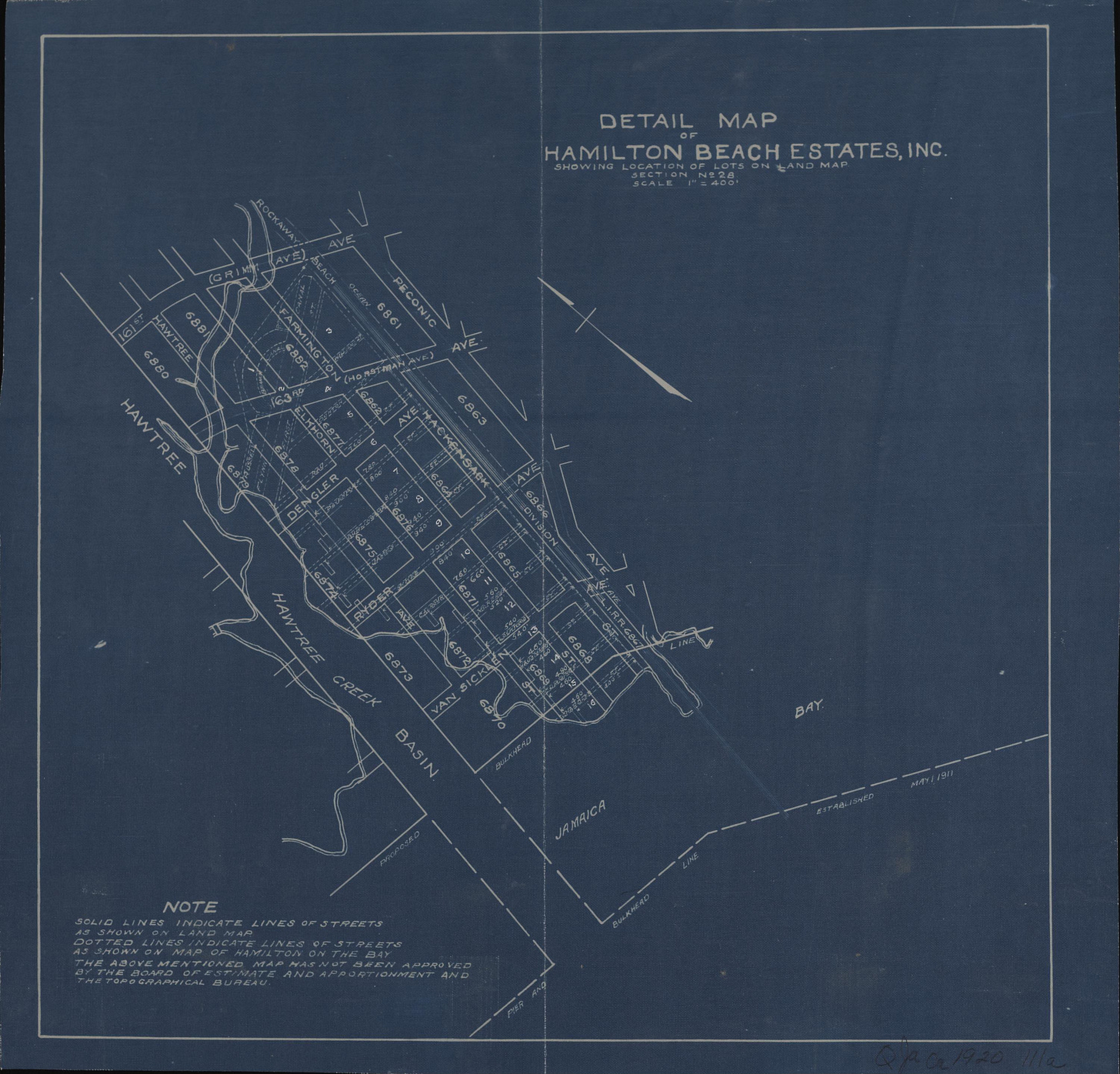

At the beginning of the 20th century, development gradually expanded to include the part of the peninsula south of Ramblersville. In the early 1920s, a modest $1,500 could secure a bungalow in the newly established Hamilton Beach Estates.

Though Hamilton Beach initially followed Ramblersville’s model of a canal-based community, the romantic vision of waterborne living eventually gave way to practicality, and roads replaced waterways.

The animation below traces the peninsula's transformation over a century—from 1924, during Ramblersville's heyday, to the well-established Hamilton Beach development in 1951, and finally, its present-day form in 2022. East of the railway corridor, you can see what was once East Hamilton Beach, the portion of the neighborhood that was demolished to make way for JFK Airport.

THE ENDS JUSTIFY THE MEANS

Hemmed in by train tracks on one side and water on the other, Hamilton Beach's street pattern resembles a comb rather than a traditional grid, a succession of dead ends that extend like short tines from 104th Street, the area's sole north-south thoroughfare.

Even within this modest sliver of a neighborhood, the quintessentially Queens phenomenon of naming streets in a way that elicits maximum confusion remains alive and well.

Despite the befuddling naming scheme, it is impossible to get lost here. The limited route options also make it an ideal place to hone your powers of observation. One thing I’ve learned during this project, revisiting the same locations days, weeks, or even years later, is how much your experience of a place depends simply on the direction you’re walking. At the most basic level, there are four ways to navigate a street: from either side and in either direction. Even those small shifts in perspective reveal surprisingly different details. Add in time of day, season, weather, and countless other variables, and the ways in which we experience a place become nearly infinite.

A city is a language, a repository of possibilities, and walking is the act of speaking that language, of selecting from those possibilities. Just as language limits what can be said, architecture limits where one can walk, but the walker invents other ways to go.

― Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

FLOOD PLAIN

No matter what direction I walked or where I looked, what struck me most was the sheer abundance and diversity of boats. Weathered rowboats, sailboats with their masts clanging in the wind, powerboats with names like Double Trouble and Senior Moment, boats wedged between houses, tucked under tarps, lurking behind fences. Boats on trailers, boats slowly sinking to the bottom of the creek.

Where most New Yorkers have MetroCards (for now), Hamilton Beachers have boats.

But life on the water comes with a price. The area is especially vulnerable to the growing threat of coastal storms and rising sea levels. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy devastated both Ramblersville and Hamilton Beach after a ten-foot storm surge inundated the entire Jamaica Bay coastline.

“You live here, you buy boots.”1

With a five-foot difference between low and high tides and nearly six feet during full or new moons, flooded streets are a regular occurrence, even in good weather. To keep their garbage cans and cars from floating away, residents monitor tide schedules with the same vigilance city drivers apply to alternate-side parking regulations.

Jutting into the once-nonexistent Hamilton Beach skyline are tall, spindly houses that sprouted up like rogue enoki mushrooms along the city’s edges after Sandy. This new, distinct architectural style, a requirement for homeowners rebuilding in the area, echoes the language of the original fisherman shacks on stilts but at a supersized scale. I’ve photographed and written about these buildings before, including in the Midland Beach newsletter and for the Wall Street Journal.

In 2018, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rejected a proposal to install protective floodgates spanning the mouth of Hawtree Creek. This plan was recently resuscitated as a component of a comprehensive $52 billion coastal resiliency initiative, one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects in New York City's history.

This visualization of projected high tide levels from the NYC Flood Hazard Mapper may make you wonder if this sophisticated system of sea gates might be the equivalent of the proverbial finger in a dike approach. No gate can hold back the tides.

Further Reading: The Rinse of Tides: Neighborhood Plagued by Monthly Flooding Sees Hope in Sea Gates

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

Most of what you hear this week are calls from the many birds that take advantage of the community's proximity to one of the largest bird sanctuaries in the northeastern United States. The end of the recording features the distant, ghostly strains of a Mexican Corrido, emblematic of the neighborhood’s gradually shifting demographic.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Sister Sonia Duthoit’s photos of Hamilton Beach come from the Queens Library archive, which houses 300 negatives and forty-nine prints of her work.

Besides her photos, the only information I could find about Sister Duthoit comes from the library’s Facebook Page.

Sister Duthoit was born in Belgium and lived in New York City from 1964 to 1968. During her brief stay, she somehow found time to study with Bruce Davidson and Lisette Model, two titans of the photo world. As of 2015, Sister Duthoit was living at Benedictine Monastery in the south of France.

You can see her whole archive here.

ODDS AND END

If you were wondering, Louis Hamilton and Chester Beach have no ties to the Queens neighborhood. In fact, these two weren't even the founders of Hamilton Beach, the company famous for its blenders, convection ovens, and crockpots. The company's actual founder and chief inventor, Frederick J. Osius, disliked the sound of his own name and paid Hamilton and Beach—both employees—$1,000 each (roughly $33,000 in today's dollars) for the right to use their names instead. This compensation seems exceedingly generous, especially given that "Osius" would have been such a great name.

Gee whiz, I remember being very young. I'm talking about three years old. My grandmother lived here. I remember my father with the oysters, lobsters and soft-shelled crabs. They caught them here.

I couldn't get over the boardwalk. It was like music to my ears the sound of it. The air, the salt air, my God. Those beautiful shells you hold up to your ear and you hear the ocean pounding. Wow, what a place. It knocked my socks off.

This excerpt is taken from Suzie Siegel’s book Tiny New York, which explores "the smallest things in the biggest city." Along with featuring NYPD's smallest bomb-sniffing dog and the city's shortest first name, Siegel interviews 93-year-old Catherine M. Doxsey, a lifelong Ramblersville resident whose memories offer a rare glimpse into the neighborhood's past.

As a former music major sound design nerd, I appreciate your field recordings.

I have never been so much in love as I am now in love with the street naming strategy deployed in Hamilton Beach.