I originally learned about Parkchester from my mother-in-law, who spent the first few years of her life in the recently opened enormous housing development that gives the neighborhood its name. Her only memory of living there was when her mother would say, “Time to air the children,” before taking her and her sister out to one of the development’s many green spaces.

When construction was completed in 1941, the 12,000 apartments of Parkchester made it the largest residential development in the country. It was praised as a “corporatized community development model,” a middle ground between public housing and suburbia.

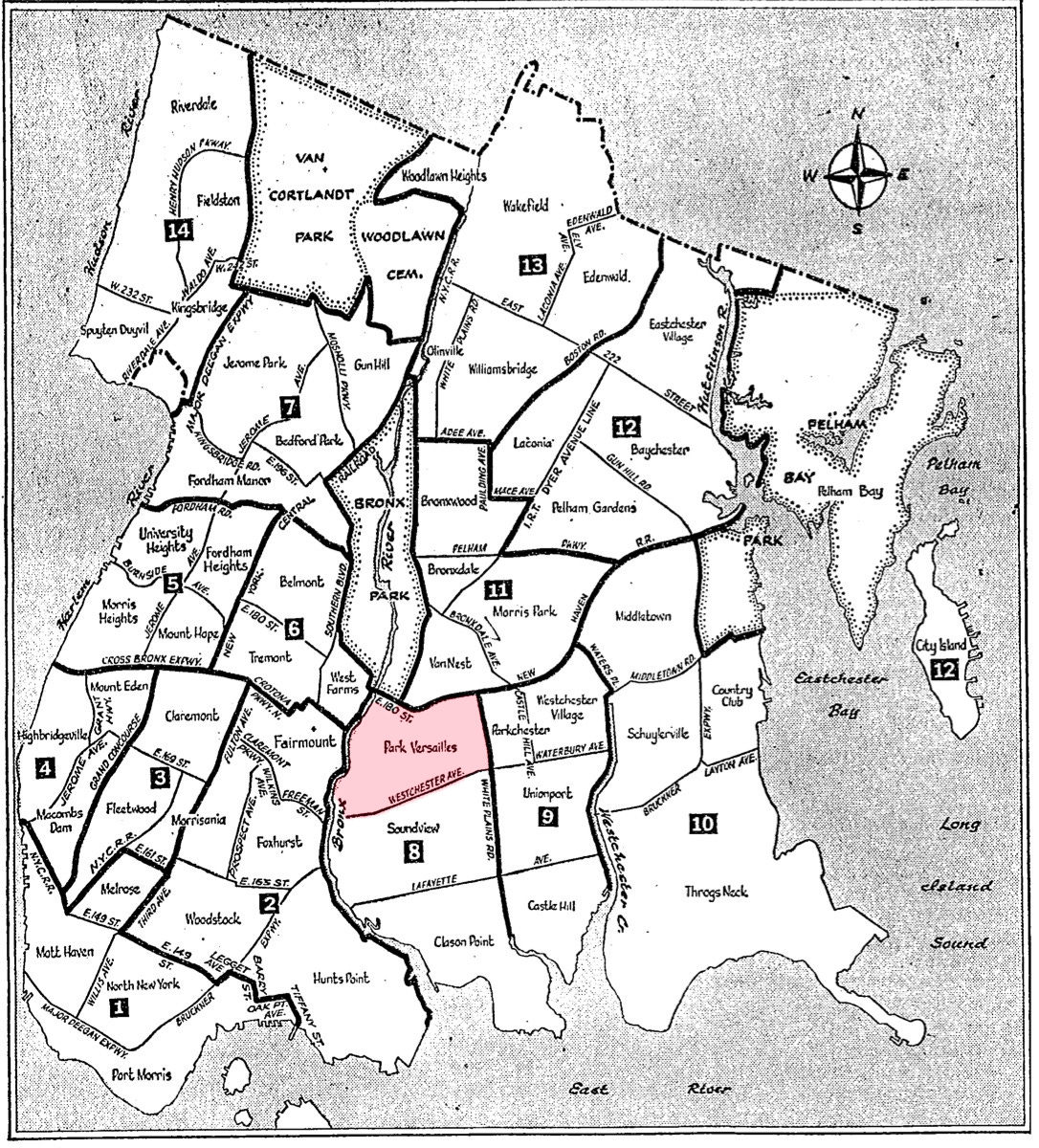

The neighborhood, a compact square circumscribed by East Tremont Avenue, Castle Hill Avenue, Westchester Avenue, and White Plains Road, is almost entirely comprised of the 171 red brick buildings of the housing development. A few streets lined with two-family homes and small businesses also fall within Parkchester’s borders.

Since the early 1990s, the neighborhood has become a haven for new Bangladeshi immigrants. Starling Avenue, also known as Bangla Bazar, has storefronts offering fresh fuchka, dress shops with the latest Bengali fashions, and butchers selling halal meat. Today, Bangladeshis account for 10% of Parkchester’s population.

Park Versailles

In the 1850s, Leonard and Mary Mapes owned a large farm that included modern-day Parkchester. When their son John inherited the place, he soon realized he was disinclined to lead the life of a farmer and decided to auction off part of the land.

He rebranded the area Park Versailles, hoping the fancy name would command a higher price than the name Mapes Farm. Parkchester is a portmanteau of Westchester Square and Park Versailles, the two neighborhoods abutting the development.

All Aboard

In 1865, the New York Catholic Protectory bought a 114-acre parcel of Mapes farm, adjacent to Saint Raymond’s church, to build an orphanage. At the time, when the city’s population hovered around 500,000, there were, by some estimates, nearly 34,000 homeless children living on the streets.

Distraught by this epidemic, Calvinist minister Charles Loring Brace created the Children’s Aid Society, which still exists today.

Those of you of a certain age who grew up in the New York metro area may remember this classic 80’s earworm:

Brace had the bright idea of getting those kids away from the corruption and vice of the city by putting them on trains and sending them off to "morally upright" families out west. Many farms were in dire need of labor, so this was a kill-two-birds-with-one-orphan kind of situation.

Handbills would announce the arrival of a train filled with orphans, and prospective parents would gather to inspect the children, counting their teeth and squeezing their muscles to gauge their suitability for farm life.

Babies and healthy boys that looked like they could handle a plow were usually picked first. Anyone not chosen had to get back on the train to try their luck at the next town. Between 1854 and 1929, over 200,000 kids were shipped to new families.

Since the largest immigrant population at the time came from Ireland, a disproportionate number of the orphans were Irish, most of them from Catholic families.

Many Catholic priests saw Brace’s orphan trains as a thinly veiled attempt to separate these children from their faith by placing them with Protestant families. Brace’s labeling of Catholics as a "stupid, foreign criminal class" made this interpretation highly plausible.

DAGGER JOHN

One of those priests, “Dagger” John Hughes, was the first Archbishop of New York and, by all accounts, not someone to be trifled with.

The Archbishop was known for his combative personality and fiery rhetoric, which he euphemistically described as a “certain pungency of style.” He had no problem calling Protestant ministers “clerical scum” or threatening to burn down New York City if any Catholic Churches were vandalized.

Hughes was approached by Levi Stillman Ives, an Episcopalian bishop who decided to switch teams mid-career and became a Catholic. Ives wanted to build a home for “vagrant and orphan children of Catholic parentage.” Dagger John thought that was a great idea.

With Hughes’ blessing and Ives’ efforts, the New York Catholic Protectory opened in 1863 and remained open until 1939, serving over 141,000 children. It was the largest childcare institution in the country.

In addition to reading, writing, arithmetic, and religious instruction, kids were taught practical, employable skills like bricklaying, baking, wheelwrighting, farming, and electrical work. They made their own shoes and clothes, which they also sold to the public, and had contracts with several large publishing houses to print and bind books in their print shop.

The Protectory was both a child welfare facility and a reform school, taking in kids with no parents, kids whose parents couldn’t provide adequate care for them, and kids whose parents had just had enough.

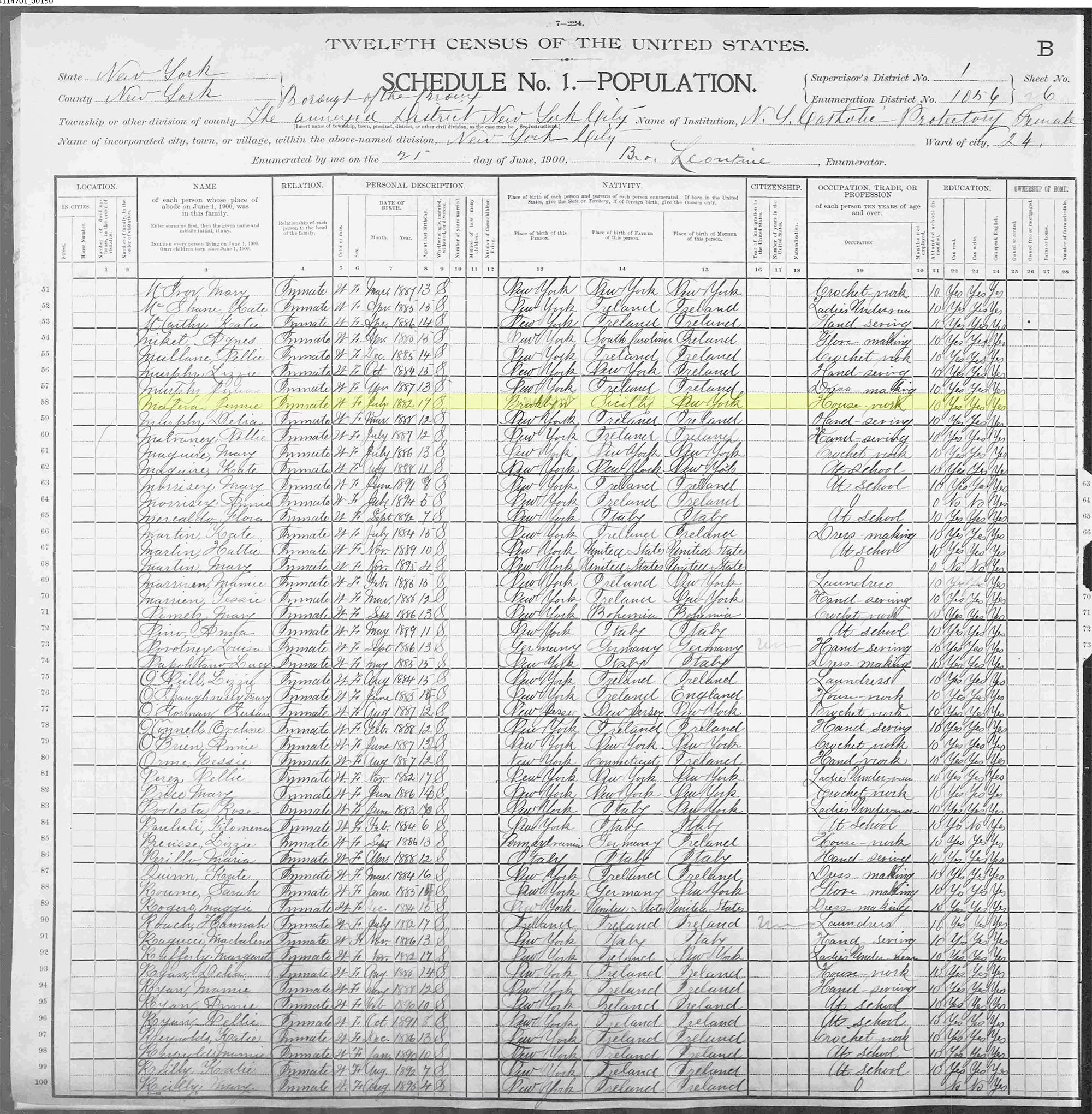

Take the case of 13 year old Jennie (“rather robust for her age”) Mafera who had been brought to the police by her parents because of her affair with 14 year old Victor Torina. Jennie would skip school to walk around the Bowery holding hands with young Vic and said she would kill herself if her love was denied.

While Victor, who had managed to procure a revolver and threatened to shoot a rival suitor, would seem more deserving of a stint at the Protectory, Jennie was the one who had to serve the time.

I was able to track down census records from 1900, and four years later, at the age of 17, Jennie was still under the watch of the Protectory.

Other “inmates” included Libby O’Brien, a 13-year-old who, in 1887, managed the impressive feat of stealing $6,000 worth of goods, the equivalent of nearly $200,000 today.

A reporter for The NY Times minced no words in describing the petite larcenist.

“Her features are regular and rather prepossessing. Her eyes are bright and sharp, and light up what would otherwise be considered a rather stupid face.”

Stupid face or not, Libby was easily able to escape the Protectory two weeks into her eight-year sentence.

She confessed her guilt with the utmost nonchalance, and told Sergt. Kenley, of the Detective Department, that they could not send her to Sing Sing, as she was too young, and that she could with the greatest ease escape from the Protectory, and she subsequently proved that she made no idle threat. After the girl had assisted the Police in recovering nearly all the property she had stolen, Justice Smith committed her to the Catholic Protectory, where she was to remain until of age. She remained there about two weeks.

Libby wasn’t alone. Escapes seemed to happen on a daily basis though less so on weekends when there was baseball to watch.

New York Lincoln Giants

At the heart of the campus was the Catholic Protectory Oval field, home turf for the Protectory Emeralds.

While the Emeralds were one of the leading amateur baseball teams in the East, the real draw was the New York Lincoln Giants, a “Negro League” team who had previously played at Fifth Avenue and 136th Street. The team used the Oval as their home field throughout the 1920s, drawing thousands of spectators to The Bronx.

The Giant’s last season was in 1930.

Eight years later, as the country shifted away from institutionalized care, the Protectory decided to sell their Bronx property. On June 1st, 1938, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. bought the 129-acre plot for $4,010,000.

MOTHER MET

In the 1930s, one out of every three city dwellers had a MetLife Insurance policy. That made it the second largest company in the country. It also meant that the company had a surfeit of cash.

Since insurance companies were legally limited in how they could invest their money, the 1929 stock market crash did not impact the industry as it had other sectors of the economy. Furthermore, with the plummeting value of stocks, investors put what little money they still had into increasing their life insurance policies.1

The depression that followed the stock market crash highlighted the city’s massive housing shortage. While NYCHA was created to help address the needs of low-income residents, a large population of working- and middle-class families fell outside the income thresholds for public housing.

With private development virtually stalled, amendments were made to state insurance codes to allow insurance companies to invest in real estate for the first time. Housing developments like Stuyvesant Town, Peter Cooper Village, Fresh Meadows, and the Clinton Hill Coops were all built by insurance companies, most of them by Met Life.

Besides providing a reliable income stream, these massive housing complexes were a way to enhance a company’s public image. The PR efforts of “Mother Met” were seen as pioneering in “legitimating corporate social responsibility as a component of business strategy,”2 a reframing that saw its apotheosis in 2011 on the campaign trail when Mitt Romney famously declared that corporations were people too.

On the plus side for Romney, the uproar over the corporations soundbite shifted the focus off of his much-maligned decision to strap his dog Seamus to the roof of his car during a family vacation.

A CITY WITHIN A CITY

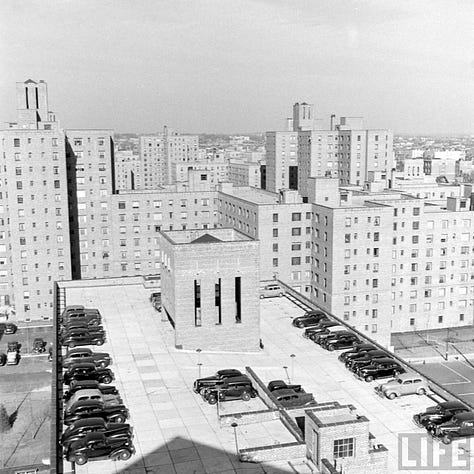

When the Parkchester development was completed in 1941, its 12,272 apartments spread out over 129 acres made it the largest housing development in the country.

The development, designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, the same firm responsible for the Empire State Building, had 51 apartment buildings, ranging from seven to thirteen stories, with room for nearly 40,000 residents.

In addition to housing, Parkchester had over 500,000 square feet of commercial space, including a drug store, a grocery store, a 2,000-seat movie theater, and the country’s first Macy’s branch. Upon its completion, it was the second most valuable property in New York City after Rockefeller Center.

From a landscaping perspective, Parkchester is perhaps the most successful of the city’s housing developments inspired by the “Towers in the Park” concept espoused by Le Corbusier in his book Radiant City. The four quadrants of buildings (North, South, East, and West) all feature large green spaces at their center with a network of landscaped tree-lined paths weaving throughout.

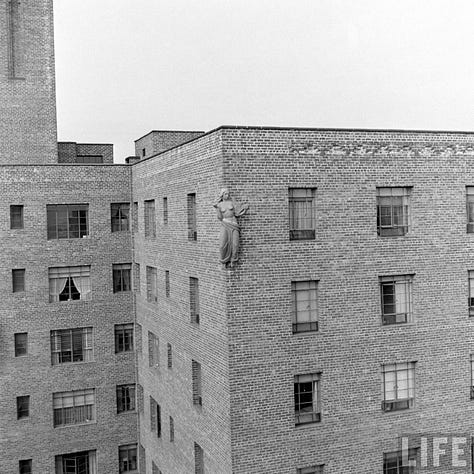

Parkchester’s most recognizable feature is the over 1000 terracotta statues and plaques that adorn the corners and doorways of the complex’s 171 buildings. The whimsical, often brightly painted sculptures include bullfighters, flamenco dancers, possessed children with evil cats, folk singers, seals, and a terrifying kid who looks like he has a Cordyceps brain infection playing the accordion.

The statues may have been colorful, the tenants...not so much. For the first 28 years of Parkchester’s operation, the development’s apartments were exclusively rented to white families. In 1968, the city's Human Rights Commission accused MetLife of “deliberate, intentional, systematic, open and notorious” exclusion of non-whites. After the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, the insurance company signed an open occupancy pledge agreeing to stop their discriminatory practices. A few months later, they sold the development.

Real estate mogul Harry Helmsley headed the investment group that purchased the property. Unlike “Mother Met,” Helmsley felt little obligation to keep Parkchester in pristine condition and began to let the property slide into a gradual decline.

Helmsley took advantage of relaxed regulations to turn the rentals into condos. Those tenants who couldn’t afford to buy their apartments were not evicted, but if they needed help with a leaky pipe or a broken fridge, they could be waiting an awfully long time. It got so bad that in the mid-90s, the New York Post called Parkchester one of the ten worst buildings in New York City.

In 1998, the Parkchester Preservation Corporation bought Parkchester’s unsold apartments and leases from Harry’s widow, Leona, for 4.5 million dollars, which incidentally was less than half the amount of money Helmsley left for her Maltese in her will.

Over the next six years, the Parkchester Preservation Corporation spent $250 million on renovations, including asbestos abatements, electrical upgrades, new plumbing systems, and installing more than 70,000 new casement windows.

In yet another example of history repeating itself, a yearslong investigation that concluded this past August found that the Parkchester Preservation Management company engaged in housing discrimination by blocking tenants with housing subsidies from renting in the development. They were forced to pay $1 million in civil penalties, the highest ever ordered for violations under the New York City Human Rights Law housing provisions, and had to make 850 apartments available for housing voucher holders.

SIGHTS AND SOUND

This week’s audio features a recording of the man playing guitar and singing outside of the Chang Li supermarket pictured below.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

German-born photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt is probably most known for his picture of a sailor kissing a woman in Times Square, V – J day in Times Square. It was just one of the 90 covers he shot for Life magazine, which employed Eisenstaedt as a staff photographer for over 35 years.

Life magazine called him “the dean of today’s miniature camera experts,” transitioning photojournalism from the bulky press cameras and flashbulbs favored by his predecessors to a more candid style enabled by handheld cameras like his favorite Leica IIIa.

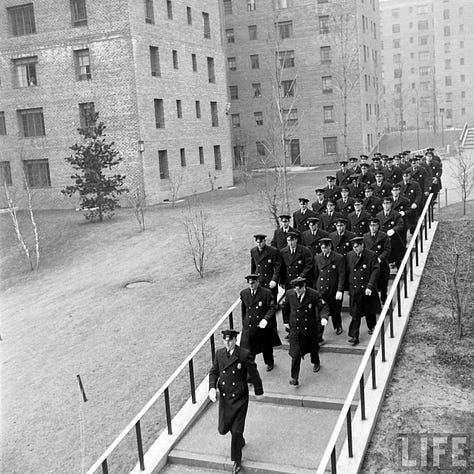

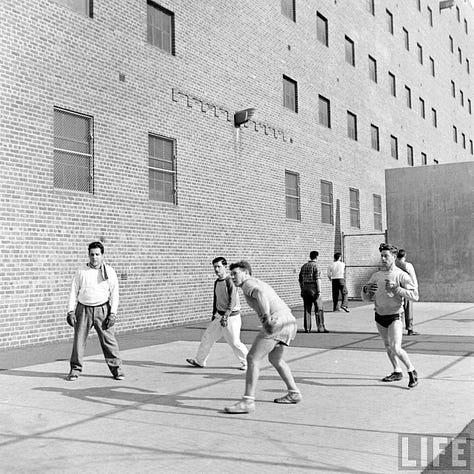

In March of 1942, Life assigned Eisenstaedt to shoot a story on Parkchester. He exhaustively documented (on a medium format camera this time) the buildings, people, and goings on in the new development.

ODDS AND END

If you’ve made it this far and still have the Children’s Aid Society jingle stuck in your head, sorry! Here is an “earworm eraser,” a 40-second audio clip designed to evict those unwanted melodies that refuse to vacate your auditory cortex. Particularly useful during the holiday season.

Famous current and former Parkchester residents include Night of the Living Dead director George A. Romero, civil rights icon Claudette Colvin who refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus 9 months before Rosa Parks, and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez who also represents the area in congress. Here is a picture Annie Leibovitz took of AOC in her apartment shortly after her election to office.

Ralph Fasanella (1914–1997) was a self-taught American artist born in the Bronx to Italian immigrant parents. He worked several jobs and was a labor union organizer. He began painting in his 30s to help with his arthritis. You may have seen his “Subway Riders” painting in the Fifth Avenue-53rd Street Subway Station. He also spent some time in the Catholic Protectory, which inspired his 1961 painting, “Catholic Protectory Line-Up.”

There is no denying that Archbishop Dagger John Hughes had a cool nickname, but did you know that the movie director John Hughes, responsible for iconic 80s films like The Breakfast Club, Planes Trains and Automobiles, and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, also had a nickname? Spike McNally

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/tanaka_fiduciary_landlords_final_4-18-17_0.pdf?t

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/tanaka_fiduciary_landlords_final_4-18-17_0.pdf?t

There are some really swell pictures in this substack. Thanks for sharing.

Wow. This issue had me wondering about the history of abuse at those children's homes, the fate of the children who went out west, and where children who reached the end of the line with no one adopting them went.