When New Brighton was founded in 1834 by Thomas E. Davis, "the greatest real estate speculator of his time," it encompassed the entire northeastern tip of Staten Island, from Tompkinsville to Snug Harbor.

Today, the name refers to a much more modest parcel of land that runs from the waters of the Kill Van Kull (the tidal strait between Staten Island and New Jersey), between Jersey Street and Lafayette Avenue, up to Brighton Avenue.

Davis emigrated from England to New Jersey in the early 19th century with plans to establish a whiskey distillery. When that venture failed, the “cool, shrewd, far-seeing man” pivoted to real estate instead.

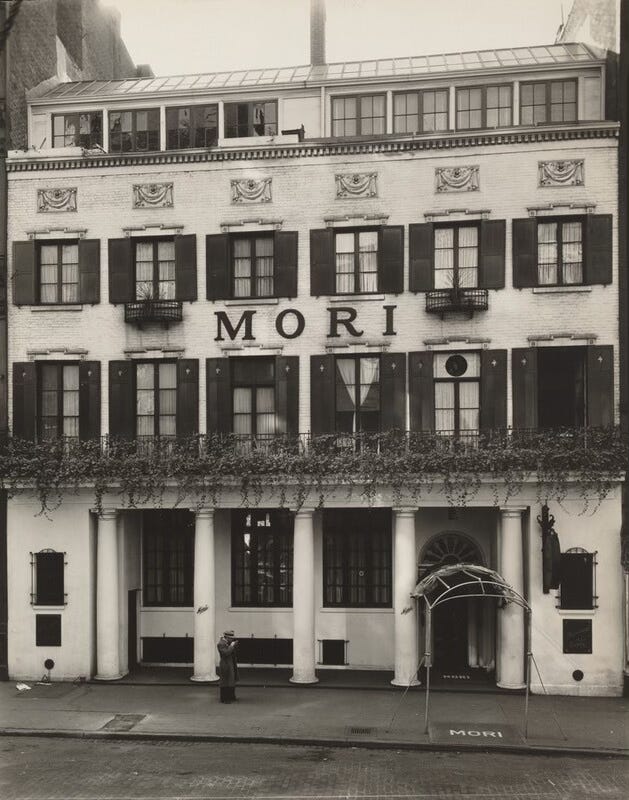

He got his start building a series of row houses on what would later become St. Marks Place in Manhattan, and developing the western end of Bleecker Street, including 144 Bleecker, captured here by Berenice Abbott in 1935.

His “grand coup” came when he and other speculators formed an association that secured a $479,000 loan to build houses and hotels along the north shore of Staten Island, from the quarantine station to Snug Harbor. They named the area New Brighton after the British seaside resort. During the Panic of 1837, they were forced into foreclosure but eventually bought the land back for $200,000. By the time Davis died, New Brighton had developed into a fashionable summer resort, and the land was worth an estimated five million dollars.

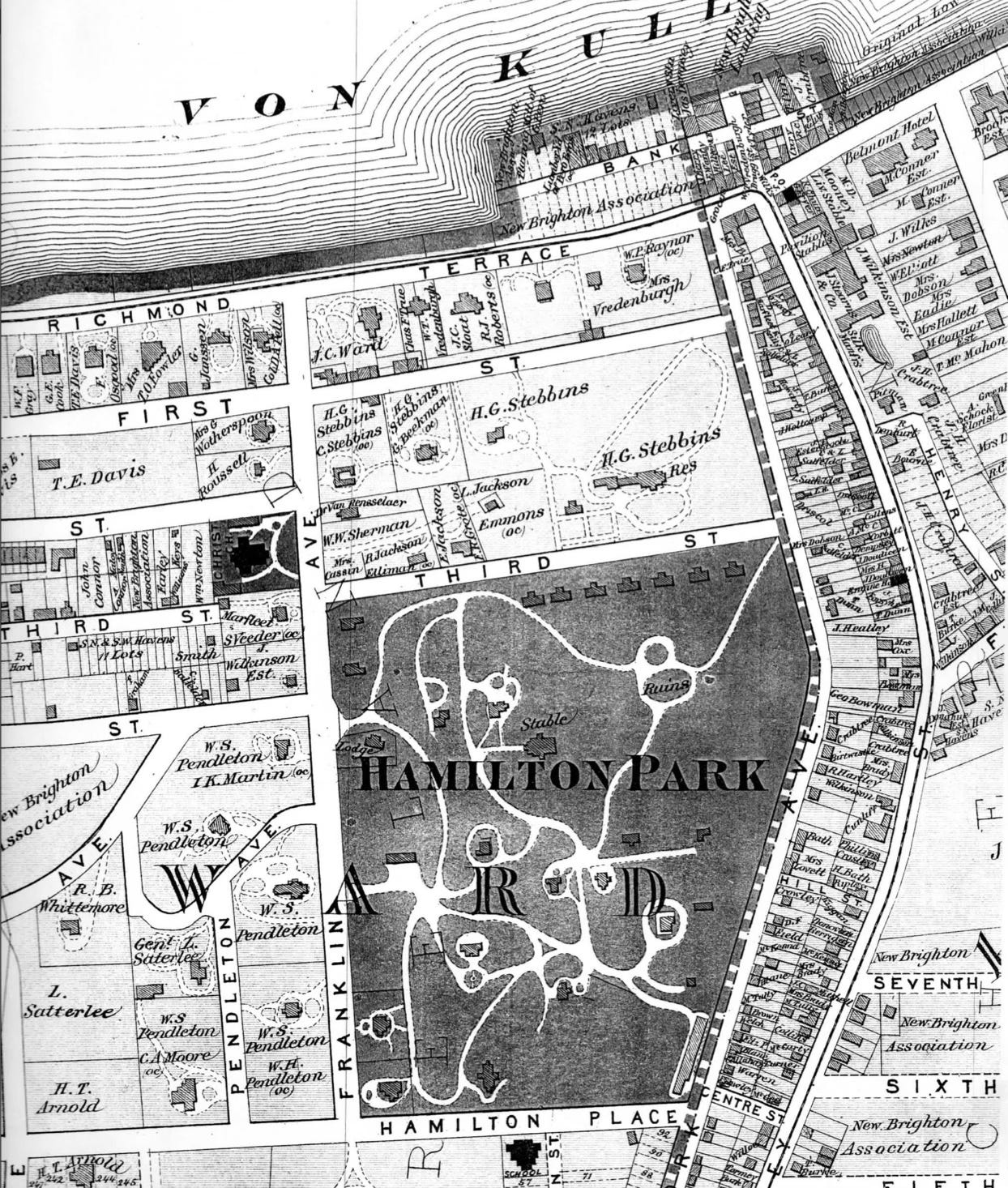

HAMILTON PARK

In 1851, Charles K. Hamilton and his wife Margaretta purchased thirty-two acres in New Brighton. They built several “cottages” and a series of curving roads, laying out what is considered one of America's earliest suburban communities.

They called it Hamilton Park, and it was, by all accounts, a beautiful setting with shared green spaces and a communal stable. But Staten Island real estate proved a risky proposition. Hamilton defaulted on his loan in 1881, and the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York foreclosed on the property.

A few buildings from that era remain, including this green Gothic Revival house built in 1855 for lithographer William S. Pendleton and later occupied by envelope magnate William P. Raynor.

PLASTERED

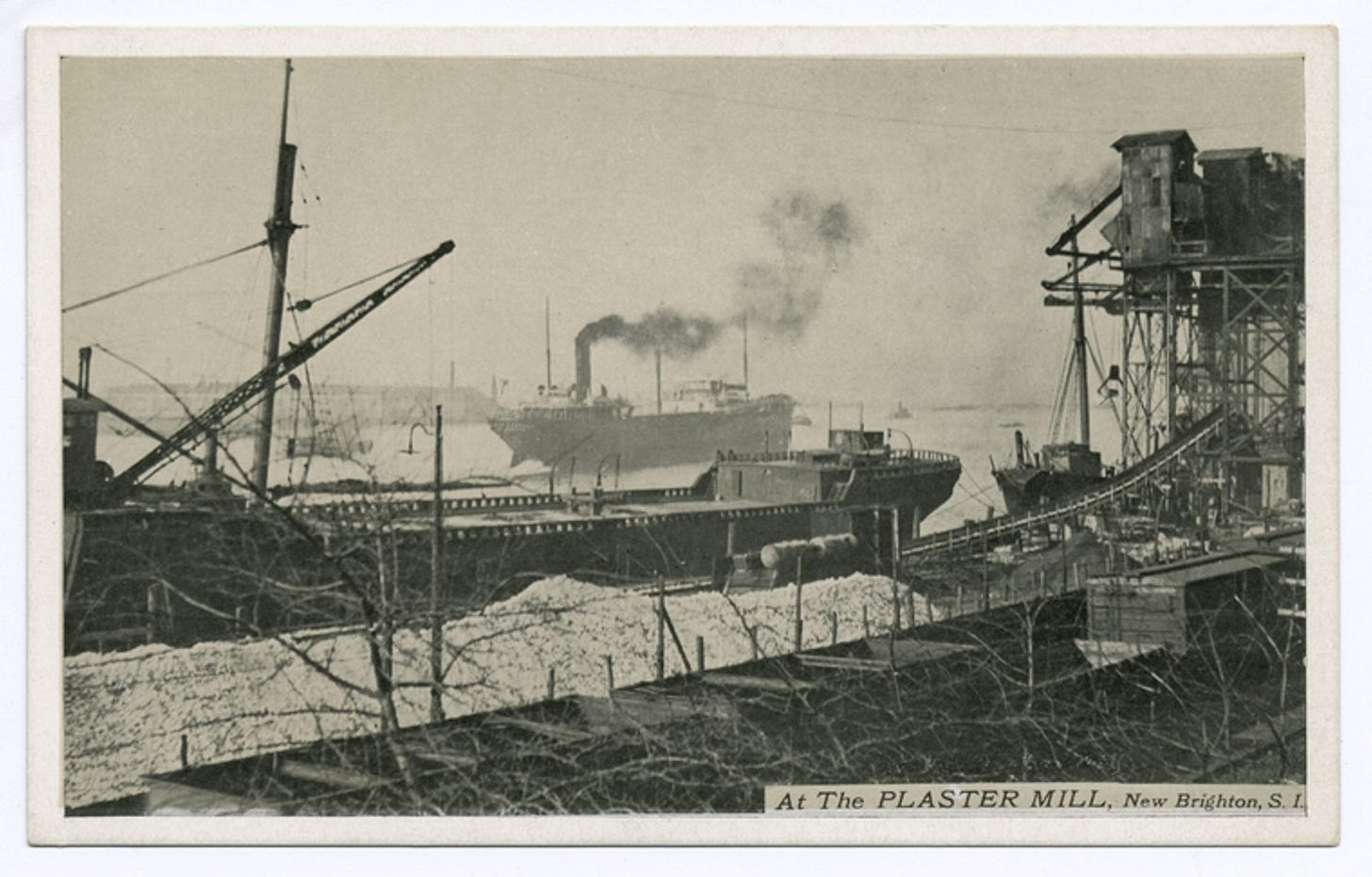

By the late 19th century, New Brighton’s waterfront was home to several major industrial operations that helped fuel the neighborhood’s growth. One of the largest employers was the Windsor Plaster Mills, run by the J.B. King Company. Built in 1876, the factory specialized in wallboard made from gypsum mined in Nova Scotia and shipped south on schooners owned by Jose Berre King.

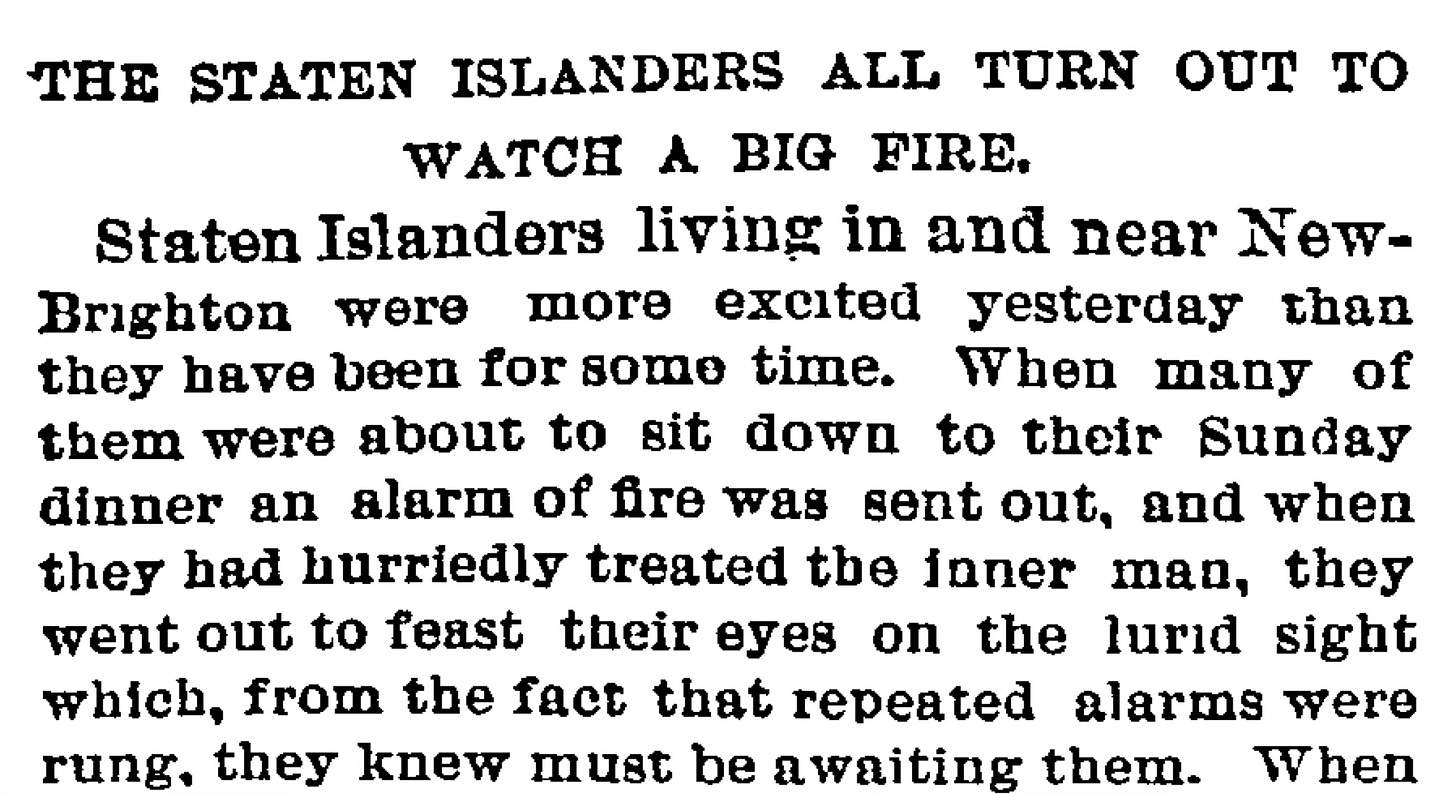

In 1885, much to the delight of a gathered crowd, the factory burned to the ground. A newspaper reported that spectators “thoroughly enjoyed the rivalries of the various (firefighting) companies who seemed far more anxious to see which hose would send the water highest than to harmoniously fight the flames.”

Some firemen, uninterested in engaging in a game of whose hose is bigger, spent the afternoon at the local saloon, where they instead “played havoc with the foaming beverage.”

In the end, "notwithstanding the herculean exertions of the firemen, both at the beer taps and with Siamese nozzles," the entire mill burned to the ground.

It was rebuilt, burned down again in 1901, and rebuilt once more the following year.

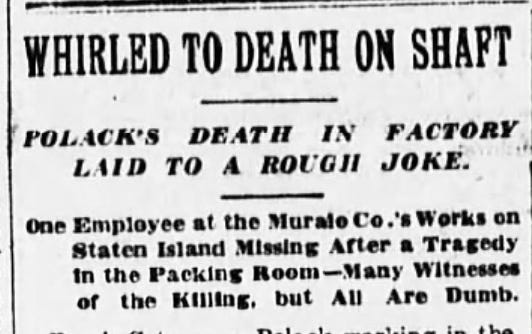

FRANK GETZNER

While the repeated rebuilding efforts were an impressive show of resilience, recently arrived Polish immigrant Frank Getzner probably wished the J.B. King company had just cut their losses. On July 14, 1906, half of Getzner’s limbs were found hanging from a rope attached to the revolving shaft of a flywheel in the factory loading dock. The rest of his body lay mangled on the ground below.

At first, the incident was reported as a tragic accident. Then, as a prank gone wrong. Eventually, police determined it to be murder, revenge for Getzner reporting a coworker, listed only as “No. 203,” for his poor performance.

Not one to handle criticism well, No. 203, an extreme devotee of the “snitches get stitches” ethos, whipped up his coworkers into a homicidal frenzy. At the end of the night shift, they tied Getzner’s leg to a rope fashioned from gypsum sacks, threw it over the flywheel shaft, and watched as his body was torn apart.

Dangling by the rope from the shaft was a human leg, and further an arm, clutching the rope with the convulsiveness of a death grip. Below on the floor lay the bleeding body of Getzner, horribly mangled, with the face battered almost beyond recognition. The men turned away sick at heart. The shaft kept revolving with the ghastly evidence attached to it.1

When police finally concluded that tying a man’s leg to industrial machinery was more than a prank, they arrested 50 workers. None of them had anything to say, and No. 203 had slipped away unnoticed.

Eventually, eight workers were charged with Frank Getzner’s death: Frank Tiro, Antonio Votilla, Frank Lugeri, Frank Buerdo, Joseph Ricardo, John Ricardo, Tony Ricardo, and (the lone non-Italian) Adam Gashenski. I couldn’t find much more about No. 203, except that his name was Frank Ricardo, which suggests that at least two of his accomplices were likely relatives, and that Frank was a very popular name in the early 20th century.

COLLAPSE

With the mill and other operations like the Crabtree and Wilkinson silk factory and the Procter & Gamble factory in nearby Mariners Harbor, there was an acute need for affordable housing on the borough’s north shore. Though tenements are mostly associated with Manhattan, Staten Island had a few of its own. Smaller in number and in scale, they were still beset by the same problems of overcrowding, poor ventilation, and substandard construction.

On August 11, 1937, a massive storm dumped several inches of rain on the city. Three tenements built for factory workers at 1, 3, and 5 New Street, where the Richmond Terrace Houses now stand, were quickly inundated by nearly six feet of water. The area had long been prone to flooding, but the speed and volume of water, some of which came from an overflowing sewer, proved catastrophic.

“The houses just folded, they just slipped from under your eyes, like magic… then for a few seconds you couldn't hear anything but the water and the crunching of the bricks.”2

Nineteen people died in the collapse.

SALT

In 1924, United States Gypsum acquired J.B. King’s Windsor Plaster Mills and continued operating the factory until 1976, when the Atlantic Salt Company took over the site. Nearly all the gypsum-era structures are gone, replaced by a four-story-high ridge of salt stretching along New Brighton’s northern edge. These towering salt mountains, a variegated strata of white, beige, and pink, loom behind a tall chain-link fence, partially covered in thick vinyl tarps.

The salt arrives from around the globe on enormous cargo ships carrying up to 50,000 tons each. After docking at the company’s terminal on the Kill Van Kull, cranes unload the salt onto the massive mounds lining Richmond Terrace. Fleets of trucks then distribute it across New York City, Long Island, and the Hudson Valley.

Although upstate New York contains some of the country's largest salt deposits, it’s significantly cheaper to import the salt by ship from countries like Chile, Ireland, and Egypt.

Different locations produce distinctly colored salt. Chilean salt, mined from the Atacama Desert, carries a slight pink tint. Dominican salt has a greenish hue, Irish salt is brown from peat, while Egyptian salt appears gray. Regardless of provenance, all of it ends up intermingled on the same Staten Island piles—and once it has melted the city’s ice and snow, the salt begins its gradual journey back to the sea from where it came.

Landing Studio, an architecture and urban design practice, put together a fantastic presentation on the Staten Island Salt Pile featured on Urban Omnibus here: SALT PILE

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

Trigger warning: This week's field recording starts with the sounds of a pickleball round robin. You can always skip ahead to the second half, which features a far more relaxing soundscape captured from the banks of the Kill Van Kull.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

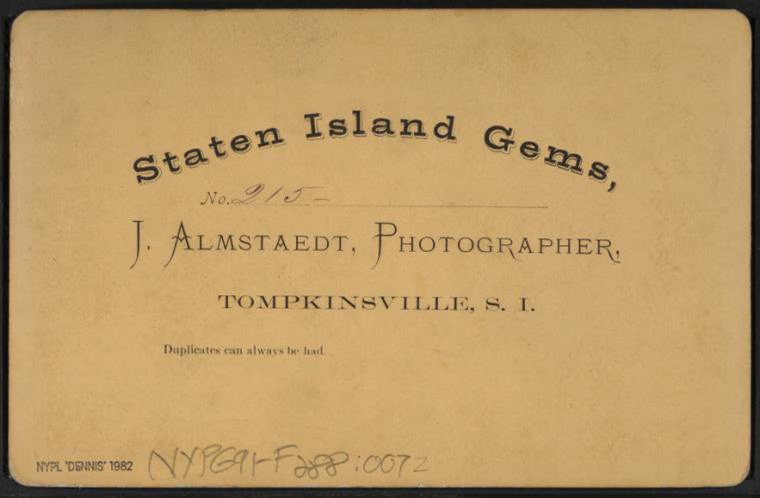

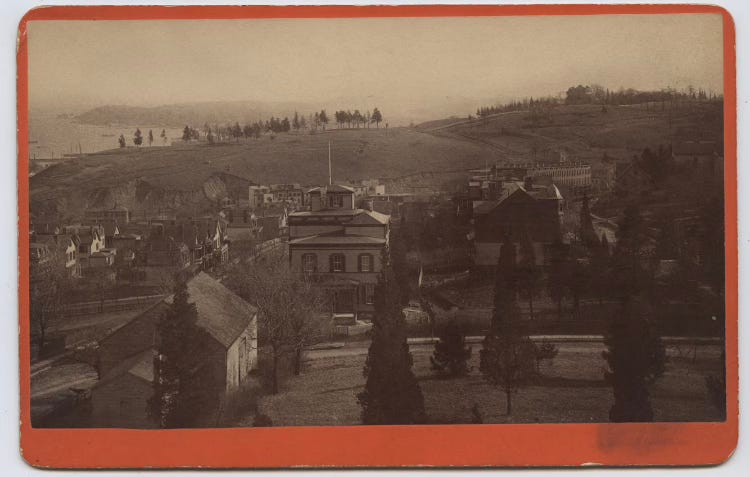

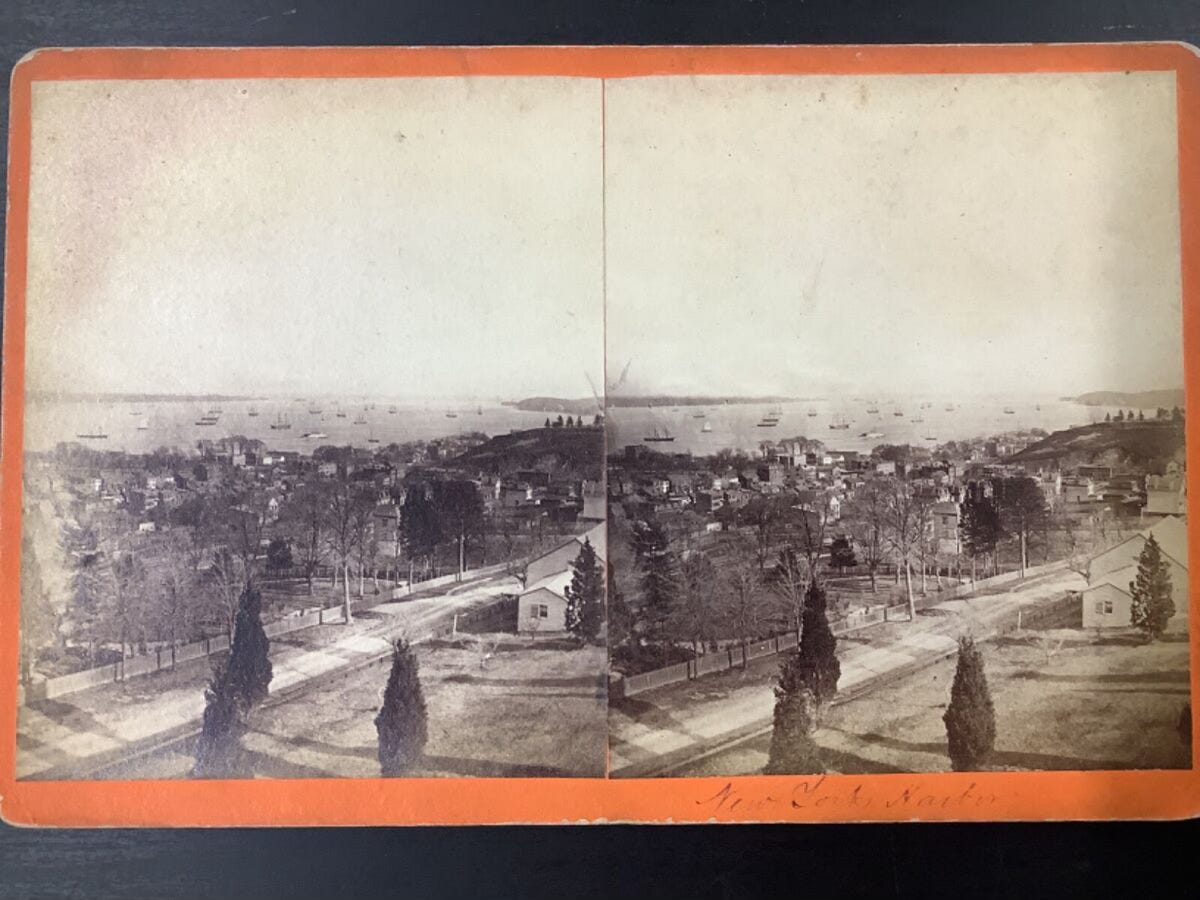

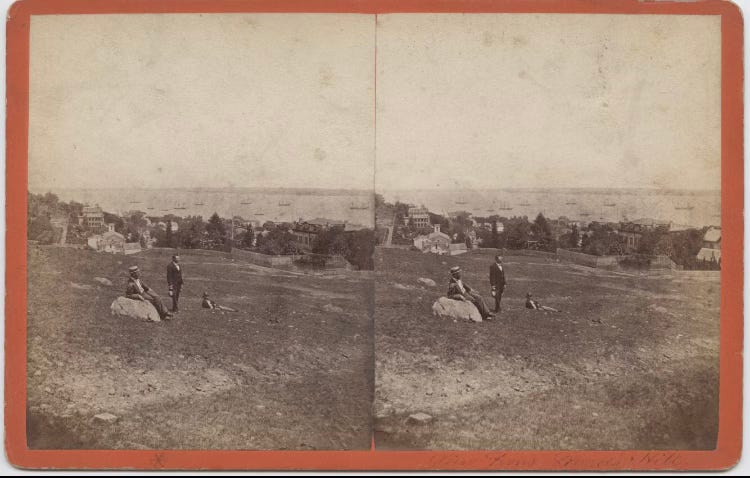

There isn’t much information available on Isaac Almstaedt, one of the most prolific documentarians of Staten Island at the end of the 19th century. At age 22, the Tompkinsville resident was working at a Wall Street firm until the Panic of 1873 left him jobless. Like Thomas E. Davis before him, Almstaedt pivoted, becoming a photographer.

A contemporary of Alice Austen (who appears in some of his photos), he became best known for his stereoscopic prints of Staten Island, which he called Staten Island Gems.

Stereoscopic images, created with a camera featuring two lenses spaced far enough apart to mimic the human eye, were all the rage in Victorian times. Besides the camera, a special stereoscope viewer was required to view the 3D effect produced by the cameras.

Of course, the most well-known stereoscopic viewer is the iconic View-Master, the Apple Vision Pro of its time.

ODDS AND ENDS

New Brighton has its own music venue, hidden away in one of the twelve original buildings of the Hamilton Park development. The Second Empire-style house, built in 1864, has hosted a variety of musicians, including Suzzy Roche, Alejandro Escovedo, and Graham Parker.

As a photographer, it’s hard to write about New Brighton without thinking of Martin Parr’s seminal early-1980s project The Last Resort, which documented the seaside resort of New Brighton in Liverpool. Parr's New Brighton work, now his most well-known, was not without controversy.

Though articles proclaiming the imminent shutdown of Staten Island's oldest bar began appearing in 2007, Leidy's Shore Inn lasted until May 2024. Larry Leidy was the fourth generation of his family to run the bar that his great-grandfather had opened in 1905. The building had a liquor license dating back to the 1880s—so it’s entirely possible this was the very bar where firemen, in 1885, chose to get plastered rather than fight the plaster mill fire right across the street.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1906/07/15/101788485.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1937/08/13/94411259.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

"Christ is the A"--I love it

I haven’t read this yet but I’ve come skidding in to say I live in New Brighton in the UK!!