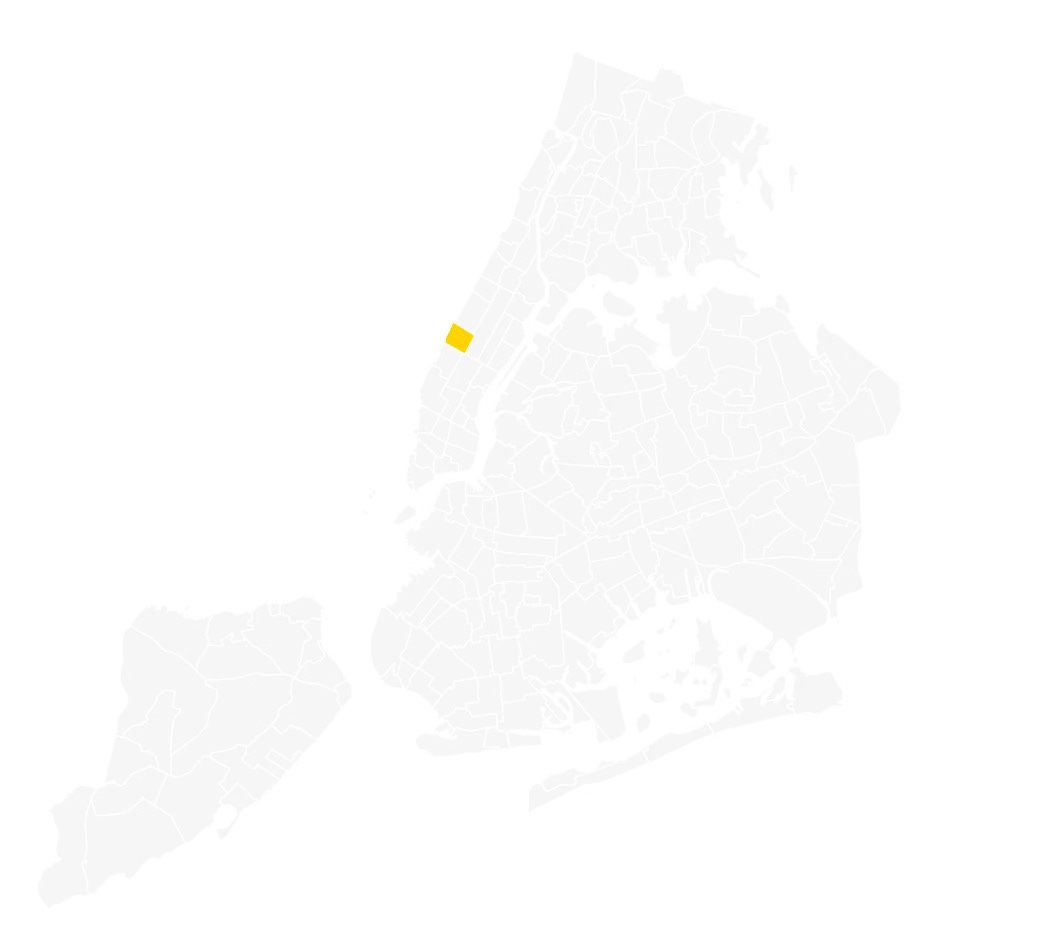

The entire stretch of Manhattan’s West Side from 42nd Street to Morningside Heights was once known as the Bloomingdale District—a broad designation for a sparsely populated expanse. Today, while the Upper West Side remains the blanket term for the area west of Central Park, distinct pockets have emerged, each with their own history and subculture. Having already written about Bloomingdale, this week I turn my attention to Lincoln Square.

OK, WHO BROUGHT THE DOG?

A walk through Lincoln Square, which spans roughly from 58th Street to 72nd Street between the Hudson River and Central Park, is like taking an architectural core sample of Manhattan—the farther east you travel, the further back in time you go. The most recent geological layer in this urban strata rises from the banks of the Hudson: Riverside South, a nearly contiguous curtain of glass-sheathed condominiums extending from 59th to 72nd Street.

The development, which was started by Donald Trump in the late 1980s, and once named, predictably, Trump City, overlooks the remnants of the West 69th Street Transfer Bridge, which was once used to move train cars from floating barges to the railroad depot along the shore. Spanning 19 buildings and housing over 8,000 people, it’s so massive that The New York Times has attempted to classify it as its own neighborhood— Riverside Boulevard—but I’m not taking the bait.

Keep heading east, and you'll find yourself in Lincoln Center, a travertine paean to the performing arts built on the rubble of a community razed by Robert Moses.

Finally, the neighborhood's eastern edge is lined with stately prewar edifices—massive limestone houses of worship and opulent Beaux-Arts and Art Deco apartment buildings marking the border of Central Park.

Between the Gothic Revival spires of Holy Trinity Lutheran and the Neo-Classical columns of Congregation Shearith Israel stands 55 Central Park West, the Art Deco skyscraper whose rooftop became the temple of Gozer, the interdimensional portal from the 1984 film, Ghostbusters.

LINCOLN ARCADE

By the early 20th century, the “slow, upward progress” of the city had made its way to the junction of Broadway and Columbus. In 1903, a commercial and residential building complex, the Lincoln Arcade, opened for business overlooking the intersection then known as Empire Square.

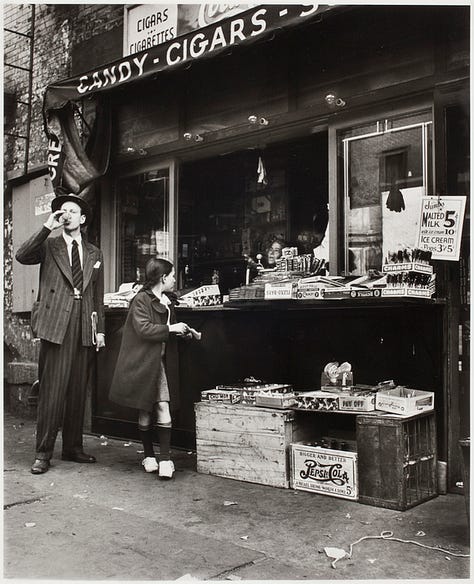

The square was a churning meeting of contending human tides. The Italians had installed their fruit shops and their groceries; the French their florists and their delicatessen shops; the Jews their clothing bazaars; the Germans their jewelers and their shoe stores; the Irish their saloons and their restaurants.

The two six-story buildings, connected by an enclosed skybridge, were built to function as multi-use space, a novel concept in those days. A panoply of businesses—candy stores, barbershops, bowling alleys, detective agencies, dentists, and dance studios—occupied the lower floors, while artists were drawn to the large skylight-lit studios on the top floor.

Despite one writer’s description of the complex as a "rookery of half-fed students, astrologers, prostitutes, actors, models, prize-fighters, quacks and dancers,"1 several notable artists and writers, including Eugene O'Neill, Milton Avery, Marcel Duchamp, and Thomas Hart Benton, lived and worked in the Lincoln Arcade.

The buildings were rebuilt after a fire in 1931 but were ultimately torn down to make way for the Juilliard School.

A WELL MEANING BABOON

In 1906, the New York City Board of Aldermen changed the name of the area once known as Empire Square to Lincoln Square. While it would seem logical that the square was named in honor of President Lincoln (after all, the city already had Madison Square and Washington Square), there is no record proving the connection.

Some people claimed the neighborhood's name came from the old Lincoln Farm, but when a reporter at The New York Times searched the Municipal Archives property records, no single landowner named Lincoln turned up. How the rumor gained traction is a bit of a mystery. The most compelling explanation is that Lincoln Square was, in fact, named after the president, but the mayor at the time, George B. McClellan Jr., didn't want anyone to know.

While it may seem surprising that a significant political figure would be so petty as to let a personal grievance influence his governing decisions, the longstanding beef between Honest Abe and the mayor's father could explain the neighborhood's murky origin story.

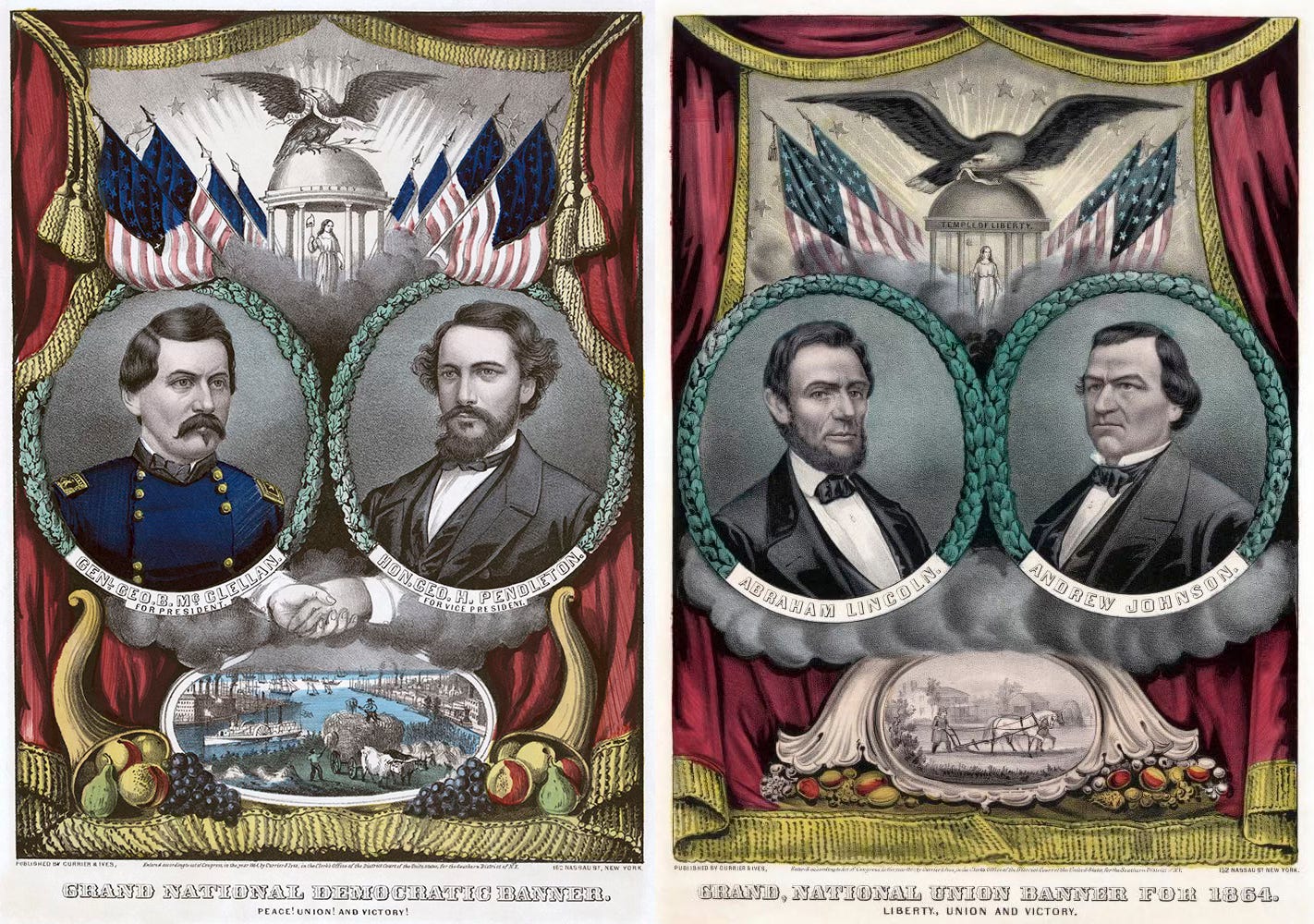

McClellan's father was General George B. McClellan, who was relieved of duties by President Lincoln (whom he called a "well-meaning baboon") at the height of the Civil War. Later, McClellan ran against Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election. While McClellan and his running mate, George Pendleton, lost the election handily, judging by these campaign posters, they undoubtedly would have destroyed the incumbent ticket in a Battle of the Bands.

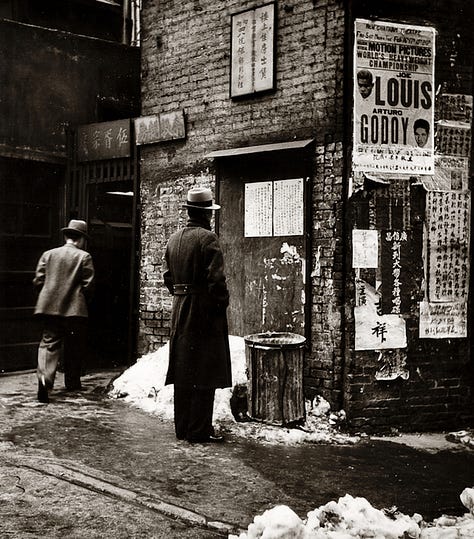

SAN JUAN HILL

On the west side of Lincoln Square, the enclave of San Juan Hill served as a key waypoint in the northward migration of New York City’s Black population. In the early 20th century, as African Americans moved from Little Africa in Greenwich Village, many settled in San Juan Hill before eventually shifting further uptown to Harlem. At its peak, the neighborhood—roughly spanning 59th to 65th Streets between Amsterdam and 11th Avenues—was home to the city’s largest Black community.

Like Lincoln Square, the origin of San Juan Hill’s name is not entirely clear. One theory links it to the 10th Cavalry, the African American regiment that fought alongside Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the pivotal Battle of San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War.

Others suggest the name was a reference to the neighborhood’s reputation for street violence, as racial clashes between the predominantly Black residents and Italian and Irish American gang (not to mention the police) dominated the headlines.

Yet, beyond its rough reputation, San Juan Hill was a vibrant cultural hub, shaped by West Indian, Southern Black, and later Puerto Rican influences. It was the nexus of New York's nascent jazz scene home to pianist James P. Johnson, the "Father of Stride Piano," who composed The Charleston between gigs at Jungle's Casino on West 62nd Street. Both the song and its accompanying dance became defining symbols of the 1920s.

What James P. Johnson did for stride piano, another San Juan Hill resident, Thelonious Sphere Monk, did for bebop.

The Monk family moved to the neighborhood in 1922, settling in building that had been built by steel magnate Henry Phipps in 1907. After he retired, Phipps dedicated a million dollar fund to constructing model tenements that offered modern amenities and spacious central courtyards designed to improve light and air circulation. The Phipps Houses on West 63rd Street (now Thelonious Monk Circle) and West 64th Street remain among the few surviving remnants of the original San Juan Hill neighborhood.

Monk, who rubbed shoulders with Johnson as a teenager, became the house pianist at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, where he forged his inimitable style. After gigs, he would return to his apartment in San Juan Hill to play music with other future bebop legends like Sonny Rollins.

Other notable San Juan Hill residents include Arturo Schomburg and Barbara Hillary, the first African-American woman to reach the North and South Poles, whom I recently wrote about in the Arverne post.

LINCOLN CENTER

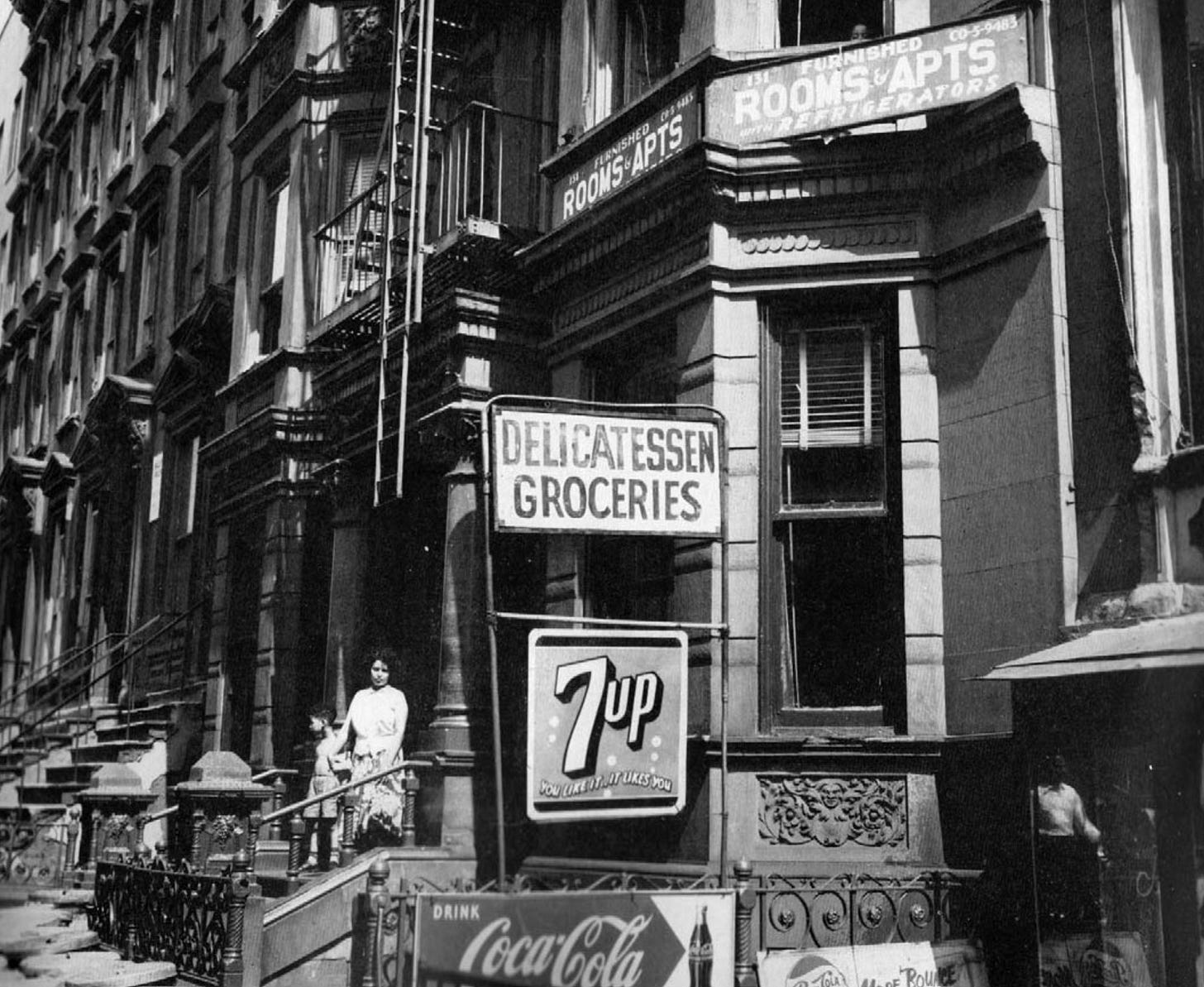

Like Barbara Hillary’s family, much of San Juan Hill’s Black population began migrating north to Harlem in the 1930s. Concurently, many Puerto Ricans moved in. To alleviate severe overcrowding, several tenements were demolished in 1947 to make way for the Amsterdam Houses, a NYCHA housing complex spanning 61st to 64th Streets.

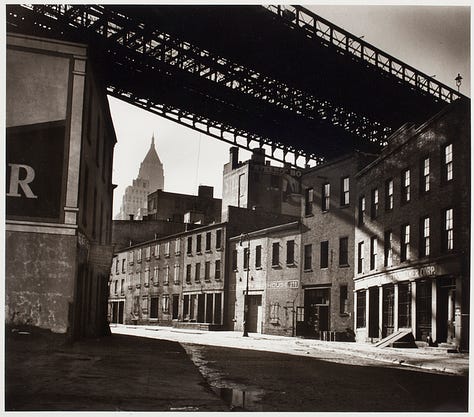

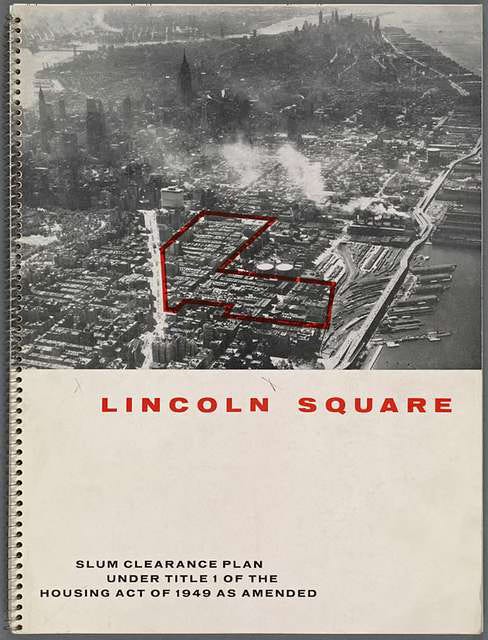

A few years later, Robert Moses, the Chairman of the Mayor's Committee on Slum Clearance, discovered that the Metropolitan Opera, New York Philharmonic, and Fordham University were all seeking new locations in Manhattan. Their needs aligned perfectly with Moses' vision of a "reborn West Side, marching north from Columbus Circle, and eventually spreading over the entire dismal and decayed West Side." Moses wasted no time in designating San Juan Hill a slum under Title I of the 1949 Housing Act, using his eminent domain powers,to begin the process of demolishing several blocks with the intention of "rearing on their ruins a huge, glittering cultural center.”2

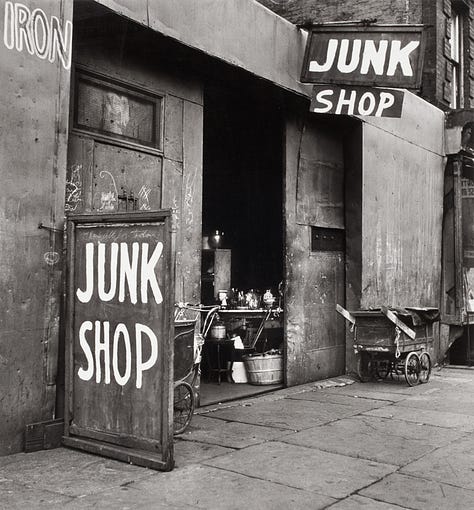

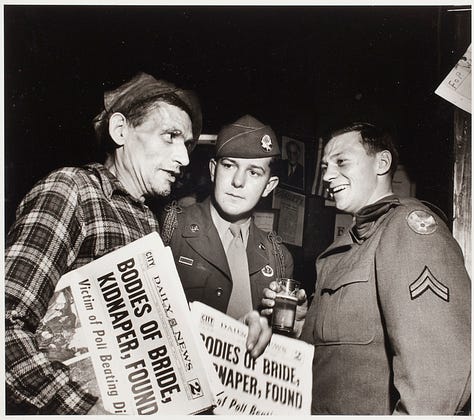

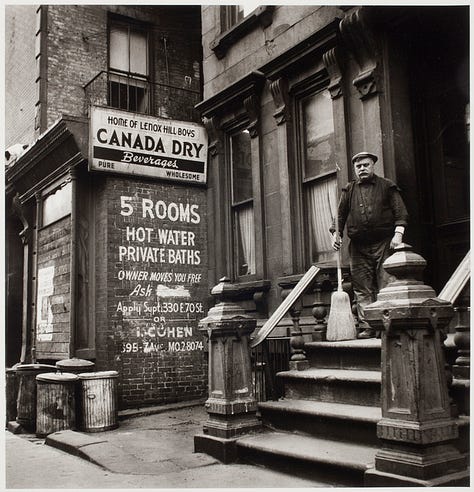

Moses spared no expense in producing lavish, spiral-bound brochures filled with maps, renderings, and photos illustrating the neighborhood's supposedly blighted condition. Like the photographs he would include as justification for his demolition of Manhattantown just a few years later, some of his chosen images seemed to contradict his claims.

Despite community opposition and multiple lawsuits, Moses prevailed. In the end, 18 blocks were razed, displacing over 7,000 families and 800 businesses.

The Lincoln Square Development Plan, led by John D. Rockefeller III, enlisted several prominent architects—including Eero Saarinen, Wallace Harrison, and Philip Johnson—to design Lincoln Center’s various cultural institutions. However, the project soon became what mired in what one critic called “architecture by bureaucracy,”3 with competing stakeholders, budget constraints, and the inevtaible clashing of starchitect egos diluting the final vision. Lincoln Center has been criticized for its detachment from the surrounding city, described as "less the vibrant source of the neighborhood's energy than the empty hole in the middle of the doughnut."4

You cannot do a job as big as Lincoln Center, I suppose, without this kind of recrimination and backbiting. So everybody pretty well hated everybody. And you’ve seen that picture with Johnny Rockefeller in the middle of the model with all of us sitting around just blissful? We weren’t speaking by then. We just sat there glaring at the camera.

Philip Johnson

FINDING MOSES

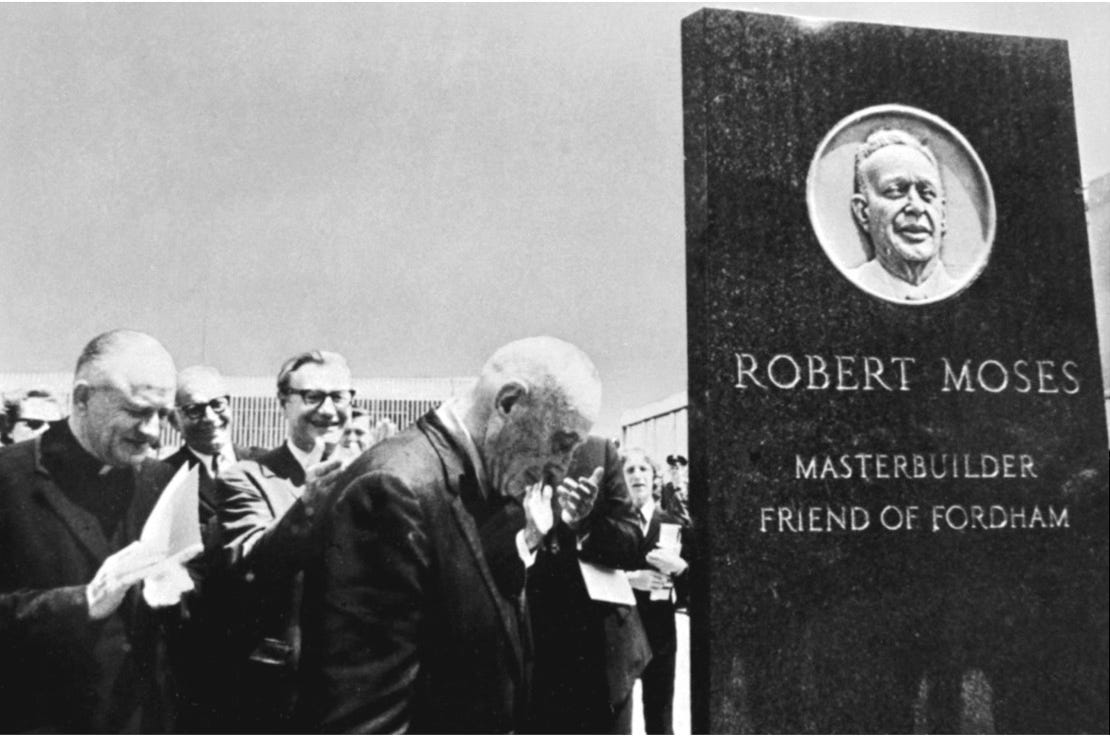

When I came across a photograph of Moses crying at the dedication ceremony of the plaza named after him at Fordham University, standing beside a plinth bearing a bronze bas-relief of his head, I decided to track down the sculpture.

As far as I know, the sculpture is one of only two Robert Moses sculptures in existence (the other is in Babylon, New York).

As I rounded the corner onto 62nd Street, I caught sight of a green-patinaed abstract sculpture with “Moses” engraved at its base.

Upon closer inspection, it became clear that this was dedicated to the Moses that parted seas, not neighborhoods.

A few yards away, I noticed a staircase tucked between two buildings. After climbing to the top, I was rewarded with an unexpected expanse of green, dotted with college students lounging in Adirondack chairs, playing Spikeball, and taking advantage of this hidden oasis—a verdant yin to Lincoln Plaza's yang.

I spotted a granite plinth that I thought might have been Moses' sculpture, but no such luck. There were several other sculptures scattered around the campus, including one of those ubiquitous giant tutu-wearing hippos and a life-size bronze ram which I later learned is the school's mascot. The ram was installed in 2017 after "years of rumors and ram-fueled intercampus jealousy." Incidentally, not every Fordham student was thrilled with the Ram's introduction into the sculpture garden. Take Alan H for example:

“I didn’t know what our mascot was, and I didn’t want to know.This is another bold-faced attempt by the university to foist spirit on our school.”5

It wasn't until I got home and started researching that I learned the plinth had been removed in 2016 after students objected to Moses' controversial legacy.

Similarly, the plaza, formerly known as the Robert Moses Plaza, has been given the less controversial if somewhat uninspired name Outdoor Plaza. In any case, if you find yourself in the neighborhood, it's worth a visit.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording features sounds from Fordham Campus, the Revson Fountain, Broadway and Riverside Park. It’s also marks a return to my binaural microphones so if you want the full immersive experience, try listening on headphones.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

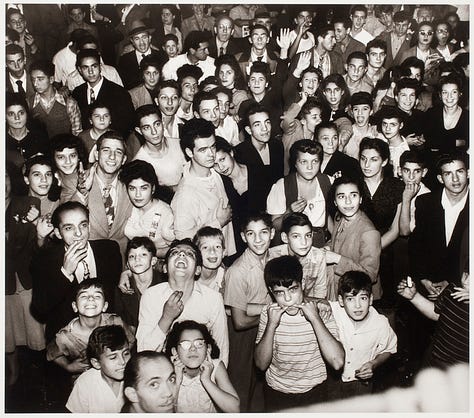

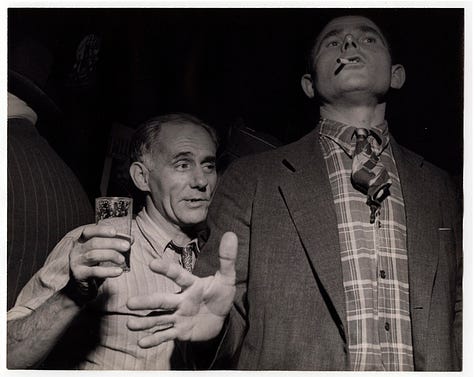

I had never heard of Lee Sievan until I came across these two fantastic photos she made in San Juan Hill in the 1940s on the Museum of the City of New York website.

Sievan, who was born in 1907 and grew up on the Lower East Side, didn't take her first photography course until 1938.

Later, she worked with Berenice Abbott and as a darkroom assistant to Weegee, whose influence can be seen in her work. In 1978, Sievan, who died in 1990, began working as a librarian and archivist at the International Center of Photography (ICP). You can see more of her work on the ICP website.

ODDS AND END

The Lost City of Trump on the “failure” of his west side development.

On the Upper West Side, Trump was overbearing, tactless and tone-deaf. His proposals were extreme, offensive and ill-conceived. Many of the people who fought him thought they beat him. They prevented him from doing what he actually wanted to do. But those buildings were built. That money was money he made. It’s the Trump paradox: He’s the most successful failer of all time.

San Juan Hill was used as both a setting and a backdrop for the 1961 film adaptation of West Side Story.

Lincoln Center has put together an extensive website detailing San Juan Hill’s history and cultural impact

For all the Gossip Girl fans out there (you know who you are), The Empire Hotel, located at the southern tip of Lincoln Square, plays a prominent role in the show’s history. In season 3, Chuck Bass “purchased the hotel as a power move.” Back in 1935, a $2.00 room would get you a single with a private toilet and lavatory. Today, the Empire Deluxe Two Bedroom Suite will set you back over $1,000. xoxo, Gossip Girl

Van Wyck Brooks (1955). John Sloan: A Painter's Life. E.P. Dutton. p. 42.

Caro, R. A. (1974). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Knopf. Chicago / Turabian

Goldberger, Paul. “West Side Fixer-Upper.” The New Yorker, 30 June 2003, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/07/07/west-side-fixer-upper. Accessed 13 Mar. 2025.

IBID

https://fordhamobserver.com/32931/opinions/newest-ram-statue-sparks-satirical-school-spirit/

Moses that parted seas, not neighborhoods.

10/10. No notes.

Robert Moses must have been the most hated man in NYC before Trump arrived.