I briefly considered limiting this neighborhood project's scope to the city's lesser-known outer boroughs. Manhattan has been exhaustingly documented; what else could I add to what is already an immense, existing body of work? Not to mention that eliminating Manhattan would conveniently shave 53 neighborhoods and a year of weekly newsletters off my list. Still, even though it is the most photographed city in the world1, it is constantly mutating, a place in permanent flux.

Manhattan’s growth is constrained by its geography; instead of sprawling outwards, it has to perpetually erase and rebuild itself. The story of Manhattan, as Lucy Sante put it, is cast in the future tense.

New York is incarnated by Manhattan (the other boroughs, noble, useful, and significant though they may be, are merely adjuncts), and Manhattan is a finite space that cannot be expanded but only continually resurfaced and reconfigured. The myth of Manhattan, therefore, is cast in the future tense.

If we can agree with Sante that Manhattan is the City incarnate, then leaving it out of this project would be a mistake. So, with that in mind, I visited my first neighborhood in Manhattan, Hell’s Kitchen.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

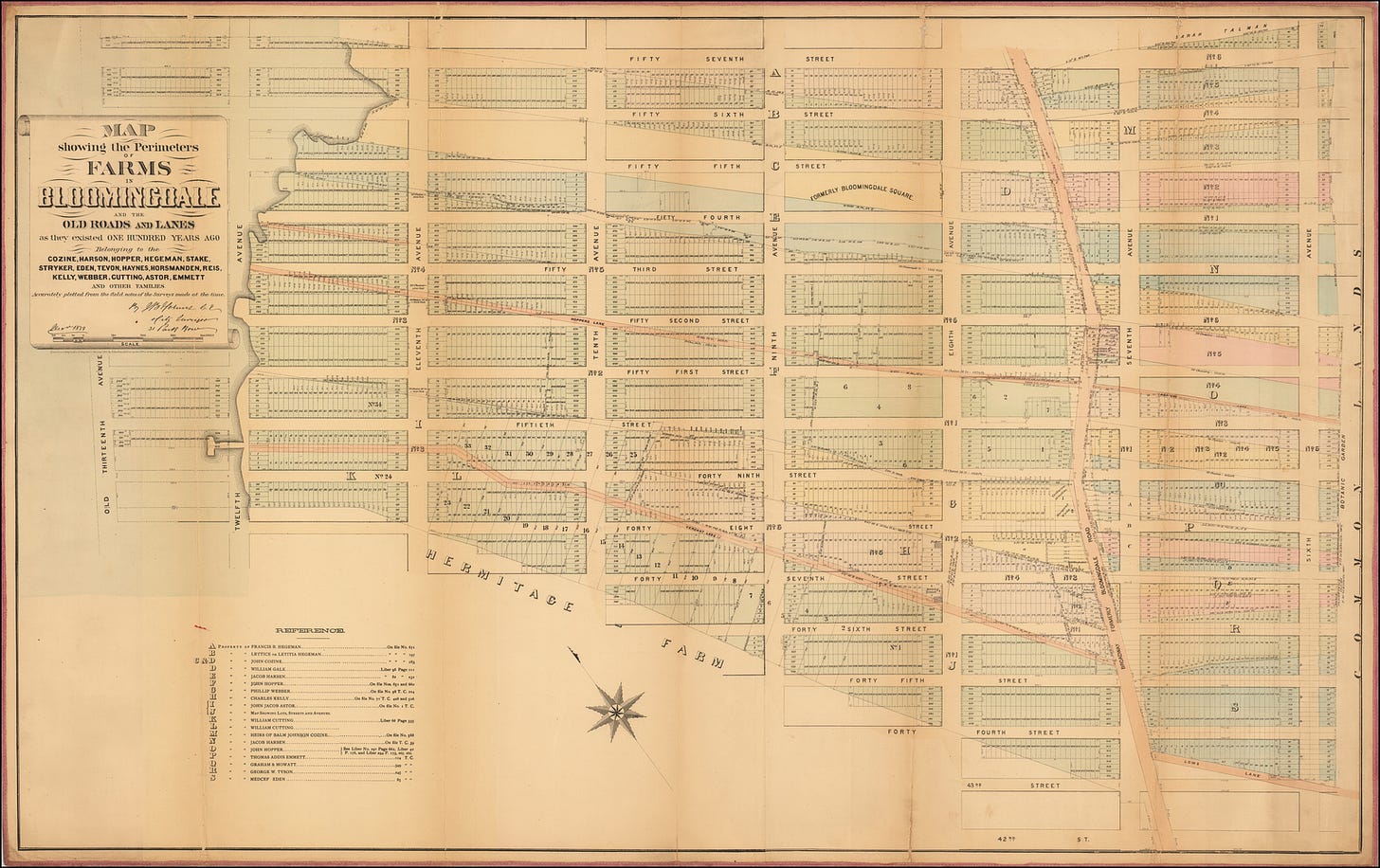

Where the name originally came from is a topic of dispute. Before it was Hell’s Kitchen, the area, mostly farmland, was known as Bloomingdale. This map by “surveyor and polygamist” John Bute Holmes shows the 1880 street grid superimposed over the original Bloomingdale farm footprint. The neighborhood’s present-day borders run roughly from West 34th Street to West 59th Street between Eighth Avenue and the Hudson River.

Some say the name originated from a conversation between two police officers describing a small riot they had stumbled upon. “This is hell itself,” one said. “Hell is a milder climate,” replied the other, “this is Hell’s Kitchen.” Others say it was a bastardization of the name of the local watering hole, Heils Kitchen. Still, others claim the name originated with Davy Crockett, who stated in 1838 that the debauched residents of the Five Points neighborhood were “too mean to swab Hell’s Kitchen.” Though Five Points was well south and east of Hell’s Kitchen, it’s possible the evocative moniker caught on further uptown. Whatever the origins of its name, with its pungent abbatoirs, cacophonous freight yards, dingy bars, and ever-feuding gangs, the neighborhood had a reputation to match.2

Rough-and-tumble tenement slums, shantytowns, smelly soap and glue factories, smoky railroads, freight yard thugs, waterfront ruffians, stables, manure carts, grisly slaughterhouses, boisterous saloons and rampant gangs like the Gorillas and the Westies, bootlegging, drunken brawls, extortion, drugs and murder.

GOPHER GANG

A surge of Irish immigrants escaping the Potato Famine in the 1850s settled in the neighborhood, drawn by the promise of employment at the nearby docks, factories, and slaughterhouses. Tenement buildings were hastily put up to accommodate the new population, and out of those arose a robust gang culture. One of the most violent of the Irish gangs that controlled the streets in the early 1900s was the 500-member strong Gopher Gang. From The Gangs of New York, Herbert Asbury:

The Gophers were lords of Hell’s Kitchen, [...] They were fond of hiding in basements and cellars, hence their name [...] every man was a thug of the first order.

Prominent Gophers (pronounced goofers) included One Lung Curran, Goo Goo Knox, Stumpy Malarkey, and Happy Jack Mulraney, whose nickname came from a partial facial paralysis that left him with an ironically permanent half smile. Legend has it that Happy Jack was arrested for shooting saloon owner Paddy the Priest after Paddy jokingly asked Jack why he never laughed on the other side of his face. Besides their predilection for subterranean hideouts, the Gophers were known for knocking out police officers, then stealing and reappropriating their uniforms. The sight of drunk and bloodied “police officers” engaged in various skirmishes on Battle Row, the block of West 39th Street between 10th and 11th Avenues, would have been quite a show for those uninformed enough to be passing by.

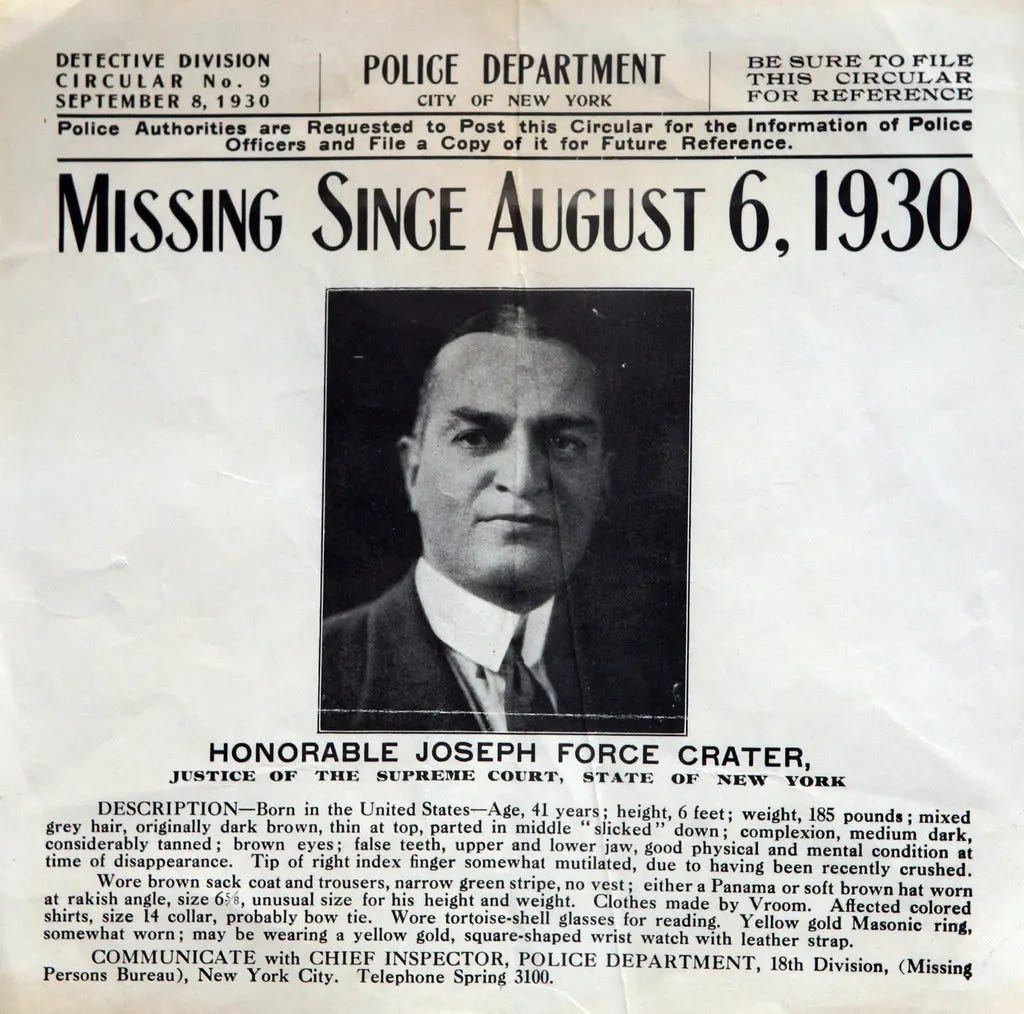

PULLING A CRATER

Besides being a hotbed of gang activity, Hell’s Kitchen was the last known whereabouts of “the missingest man in New York,” Judge Joseph Force Crater. “Good Time Joe” sat on the State Supreme Court and was known for his penchant for showgirls and his connections to the corrupt Tammany Hall political machine.

On the morning of August 6, 1930, after destroying various documents and removing the equivalent of $80,000 in today’s money from his bank account, Judge Crater had dinner at Billy Haas' Chophouse on West 45th Street. After dinner, he stepped into a cab, never to be seen again. In 1939, after years of fruitless searching, he was declared legally dead, and the case went cold. That is until, in 2005, a note was found after 91-year-old Stella Ferrucci's death claiming that Crater had been killed by Charles Burns, an NYPD officer who moonlighted as a Murder, Inc. bodyguard. According to the note, Burns and two associates buried Crater beneath the Coney Island boardwalk, now the site of the New York Aquarium. However, his remains have never been found. The case was so well known that Pulling a Judge Crater or Pulling a Crater entered the vernacular as a way of saying, “disappeared without a trace.” Ironically, the expression itself has Pulled a Crater and has fallen into obscurity. I, for one, will be using it whenever possible in the future.

JAVITS

Today, Billy Haas' Chophouse is a parking lot, and Battle Row is an off-ramp for the Lincoln Tunnel. The nearby Jacob Javits Center is home to such varied events as Comic Con, Erotica USA, and the National Stationery Show. It was also the site of Hillary Clinton’s election night party headquarters in 2016, an election that was totally fair and not rigged. Coincidentally, her opponent that night had convinced the city to build the Javits Center in its current location in 1986. Donald Trump leveraged his political connections and obtained an option to build on the rail yards (at no cost to him) in 1975, which he turned around and sold, netting him a cool $833,000. His connection with the convention center surfaced again during the Covid outbreak in 2020 when Trump reluctantly agreed to temporarily convert Javits into the world’s largest hospital at then-Governor Cuomo’s request.

[Cuomo] wanted a hospital built in the Javits convention center. We built it, but he didn’t use it. He could have used for the older people. It was brand new, not infected, no infection

The Javits Center treated 1,100 patients and administered 646,000 vaccines.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

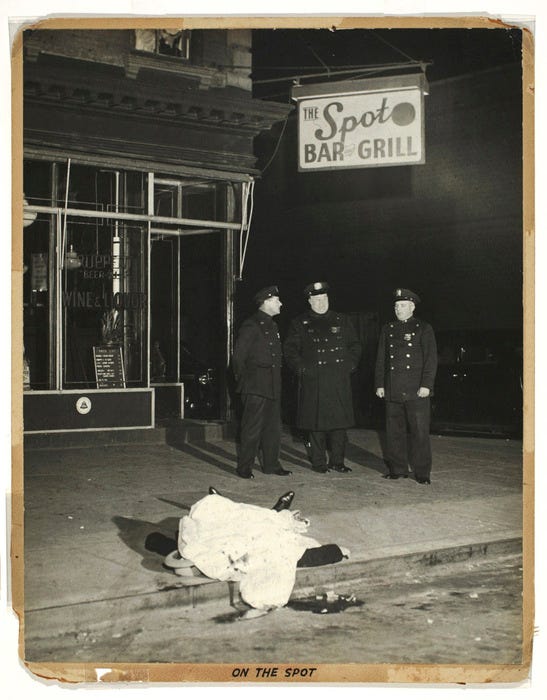

FEATURED PHOTO

This week’s featured photo is by Weegee, who, in 1938, was the only photographer with a permit to have a shortwave police radio in his car. His work as an “ambulance chaser” led him to many crime scenes throughout the city - Hell’s Kitchen was a frequent destination. He had a stamp for his photos that read "Credit Photo by Weegee the Famous." The International Center of Photography (ICP) put out the Weegee Guide to New York, a guidebook with maps of the specific locations of his shoots, including this image below at 651 Tenth Ave.

NOTES

In 1959 two 16-year-olds, in a case of mistaken identity, were stabbed to death by a member of a teenage gang, The Vampires. The infamous Capenman Murders, named because the murderer Salvador Agron (also 16) wore a cape during the crime, occurred in a playground on West 46th St. Agron was the youngest person ever to be sentenced to death in New York, though his sentence was later commuted. In 1998 Paul Simon made a musical, The Capeman, about Agron. While it cost a whopping 11 million dollars to produce, the NYTimes called it a "sad, benumbed spectacle," and the show only lasted 68 days (or about $162,000 per performance). This track, notable for its repeated refrain, “If you got cojones, come on, mette mano,” goes into the backstory of Salvador’s recruitment into the Vampires.

After the Capeman murders, in an attempt to distance themselves from the name’s negative connotations, local business owners made a concerted effort to rename the neighborhood Clinton after former mayor DeWitt Clinton. While newspaper articles and some maps will sometimes refer to the area as Clinton, this rebranding has essentially Pulled A Crater, as everyone still refers to the neighborhood by its old name.

The most photographed building in the most photographed city in the world? The Guggenheim.

Lambert, Bruce. “NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: CHELSEA/CLINTON; Hell’s Kitchen Hotter with Revivalist Fans.” The New York Times, December 4 1994, www.nytimes.com/1994/12/04/nyregion/neighborhood-report-chelsea-clinton-hell-s-kitchen-hotter-with-revivalist-fans.html. Accessed May 18 2023.