Last week, I wrote about New York City’s smallest neighborhood. This week, I cover one of its largest: Crown Heights. The central Brooklyn neighborhood is roughly one mile by two miles—easy enough to circumnavigate—but it covers nearly 1,300 acres.

Crown Heights’ borders are roughly Atlantic Avenue to the north, Washington Avenue to the west, Ralph Avenue to the east, and Empire Boulevard to the south. The Olmsted and Vaux-designed Eastern Parkway splits the neighborhood in two and, in some ways, divides the area’s Black and Jewish communities.

Crown Heights is a vibrant, diverse neighborhood. Every year, its large Caribbean American population hosts the West Indian Day Parade, which draws over a million participants. The neighborhood is also the headquarters of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement, and is where upwards of 15,000 of its followers live. Today, gentrification spreading eastward from Prospect Heights, is changing the neighborhood yet again.

CROW HILL

Until the early 20th century, Crown Heights was known as Crow Hill, a sparsely inhabited expanse of "woods, wastelands, and wild gullies" similar to nearby Pigtown. The "Hill" in the name is easy enough to figure out as the neighborhood sits on top of a terminal moraine left by receding glaciers thousands of years ago.

The origin of the “Crow” portion of the name is uncertain, with several competing theories. The most literal explanation attributes the name to the abundance of crows in the area. Another suggests it refers to a hermit who lived in the area and survived by eating said birds.

A more widely accepted theory comes from an 1873 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article which claims “crow” was a derogatory term for the area’s Black inhabitants. Lastly, some believe the name is linked to the Kings County Penitentiary, where inmates wore black-striped uniforms.

NOSEY KATE AND THE TERROR OF WILLIAMSBURG

Kings County Penitentiary, more commonly referred to as Crow Hill, was built on a plot of land between Nostrand Avenue and Rogers Avenue, spanning from President Street to Crown Street.

In 1848, it opened its doors (before quickly closing them again) to its first 13 prisoners. Though intended for criminals convicted of minor offenses, the sentences were anything but lenient: two and a half years for stealing a horse, six months for public drunkenness. Given the severity of their punishments and reports of mistreatment, prisoners’ frequent attempts to escape were understandable.

In 1872, a reporter from the Brooklyn Eagle took a tour of the prison including a visit to both the men’s and women’s wings. He described the female inmates as having “the eyes of wolves and brutal faces stamped all over with the unmistakable brands of vice.”

Notable prisoners included Owen McMann, aka “The Terror of Williamsburg,” a member of the Battle Row Gang, described as having “wicked eyes and a bullet head covered with the scars won in many a hard bottle fight.” Then there was the infamous clothesline thief, “Nosey” Kate Martin, who the reporter described as “short and stout, with a face like a bulldog just recovering from the effects of a severe fight.” Nosey Kate had earned her ironic nickname after “endeavoring to knock the neck off a gin bottle with her face, the aforesaid bottle being in the hands of an enemy at the time.”

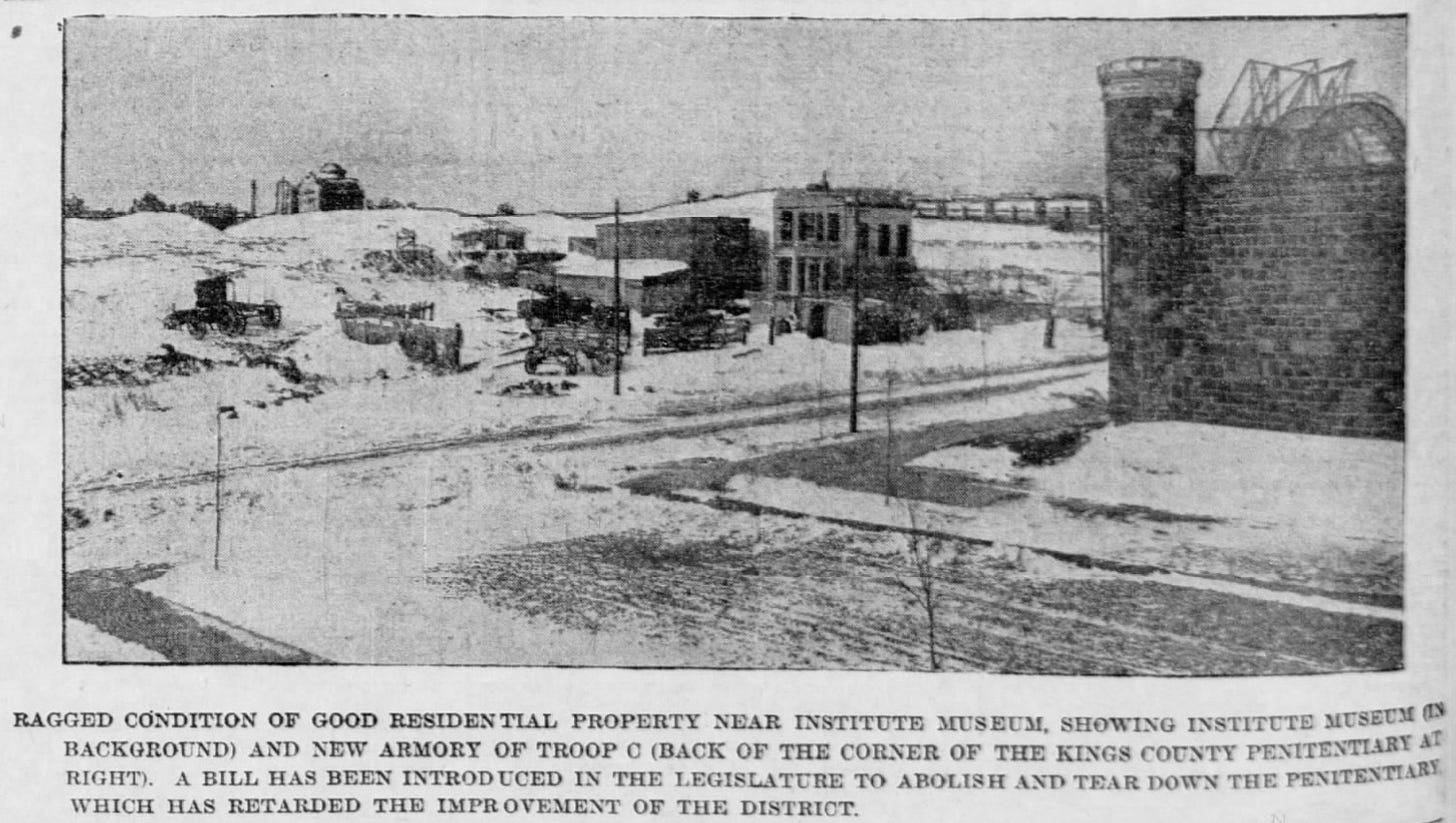

By the early 20th century, construction of Eastern Parkway had made the surrounding land highly coveted. The prison, which had seen a steady decline in inmates, was now viewed as an obstacle to the area’s growth.

In 1907, the jail was demolished, and, perhaps in an effort to distance itself from the prison’s reputation, the neighborhood was renamed Crown Heights.

WEEKSVILLE

While the penitentiary housed criminals, Weeksville emerged at the neighborhood’s eastern edge as a beacon of freedom—a settlement founded in 1838, eleven years after slavery's abolition in New York and decades before the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Panic of 1837 triggered a sell-off by wealthy Brooklyn landowners, creating an opportunity for abolitionist Henry C. Thompson, who purchased 32 lots with the vision of establishing a self-sustaining Black community. At the time, the New York State Constitution required Black men to own property to vote, a restriction not applied to white men. One of the first people to purchase land from Thompson was James Weeks, a longshoreman working at South Street Seaport and the neighborhood’s namesake.

By the 1850s, Weeksville had grown into the second largest free Black community in America with over 500 residents, complete with churches, schools, a newspaper, an orphanage and the Zion Home for the Aged. During the 1863 New York City Draft Riots, it provided refuge for Black New Yorkers fleeing Manhattan.

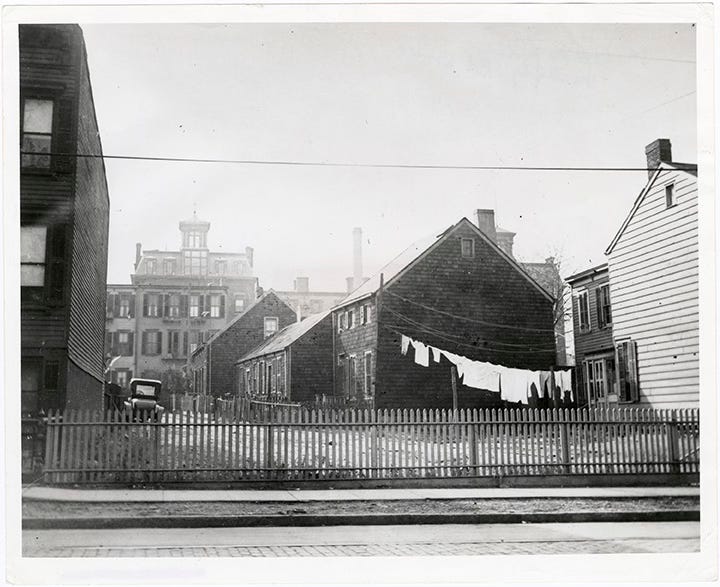

The construction of the Brooklyn Bridge and Brooklyn’s incorporation into New York City led to Weeksville’s gradual integration into Crown Heights. In the 1940s, the orphanage and senior home were relocated, and most of the community’s wood-framed structures were demolished to make way for the Kingsborough Houses.

By the 1960s, Weeksville had largely been forgotten until historian James Hurley, curious to see if any remnants of the village still existed, made an aerial survey of the area. From the plane, he spotted four surviving wooden cottages, the last vestiges of the once-thriving community. These Hunterfly Road Houses were granted landmark status and, after several years of restoration, now form the centerpiece of a museum and visitor center opened in 2013.

MILLIONAIRES’ ROWS

Crown Heights transformed dramatically over the 20th century. By 1900, it had become one of Brooklyn's most prestigious neighborhoods, with grand apartment buildings along Eastern Parkway and two separate "Millionaires’ Rows" on President Street and St. Marks Avenue.

Large churches and synagogues were built, and in 1899, the country’s first children’s museum was established at the corner of Brooklyn Avenue and Prospect Place, where it still stands today. German, Scandinavian, Caribbean, Irish, and Italian immigrants, and a particularly large Jewish population, settled in Crown Heights in significant numbers.

After World War II, the passage of the GI Bill enabled many of the neighborhood’s white residents to move to the suburbs. At the same time, immigrants from the West Indies began moving in. The blockbusting and fearmongering tactics employed by unscrupulous real estate agents and developers further accelerated white flight from Crown Heights. By 1970, a neighborhood that had been nearly 90% white two decades earlier was now 70% Black. The vast majority of the remaining white residents were Chabad-Lubavitch Jews.

THE LUBAVITCHERS

Fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe in 1940, the Lubavitchers—a Hasidic Jewish movement from Russia—established their new center in Crown Heights under the leadership of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn. After Schneersohn's death in 1951, his son-in-law, Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, took over as the movement's head. Many Lubavitchers believed Schneerson (whose visage you have undoubtedly seen plastered on the back of walk signals all over Brooklyn and beyond) to be the Messiah.

In 1969, during the peak of white flight, the Rebbe declared that "the wholesale emigration from Jewish neighborhoods…[was] a plague" and urged his followers to remain in Crown Heights rather than relocate.

The heart of the Chabad movement is the building at 770 Eastern Parkway, known simply as 770. When Rebbe Schneersohn arrived in the U.S., he was in poor health and required a building with an elevator, so the Chabad community purchased the Neo-Gothic Tudor Revival mansion to serve as their headquarters.

Built in 1920 and designed by architect Edwin Kline—who also designed Oscar Hammerstein’s Long Island mansion—770 originally served as a doctor’s office before becoming the nerve center of the Chabad movement.

Today, 770 is one of the most reproduced buildings in the world, with an estimated 35 replicas across India, Nigeria, Australia, and beyond. An article in The Forward describes its distinctive three-peaked roof as a kind of corporate logo—akin to the Golden Arches of McDonald’s.1

The building recently made headlines when a rogue, haphazardly excavated tunnel—60 feet long by 8 feet wide—was discovered connecting 770 to an adjacent building. The tunnel had been built by a renegade group of yeshiva students who had decided to take matters of expanding the synagogue's capacity into their own hands. When construction workers, hired by synagogue officials, showed up to pour concrete into the excavated areas, the students retaliated. Nine were arrested in an incident that the New York Post immortalized with its characteristic flair.

FURTHER READING: The three-decade saga that led to the Crown Heights tunnels.

RIOTS

On August 19, 1991, seven-year-old Gavin Cato and his cousin Angela were playing near Utica Avenue and President Street when a driver following the motorcade of the Lubavitcher Grand Rebbe ran a red light, jumped the curb, and struck them. Gavin was killed, and Angela was seriously injured.

Three hours later, in apparent retaliation, a group of Black teenagers fatally stabbed Yankel Rosenbaum, a 29-year-old Orthodox Jewish scholar from Australia with no connection to the accident.

For the next three days, Crown Heights was engulfed in chaos. Windows were smashed, stores were looted, and tensions between the neighborhood’s Black and Jewish populations erupted into violence. The NYPD deployed 1,500 officers to restore order, eventually ending the unrest.

Black residents claimed that paramedics at the scene of the accident had given preferential treatment to the Hasidic driver and his passengers, ensuring he was removed quickly while failing to properly tend to the young children. Many protesters saw this as emblematic of broader disparities in how the police and emergency services treated the neighborhood’s Black and Jewish communities. Jewish leaders, meanwhile, condemned the violence and the protesters’ anti-Semitic invective and criticized the city's delayed response. The riots caused an estimated one million dollars in damage and deepened the neighborhood's divisions, becoming a painful chapter in Crown Heights' history that would take years to heal.

FURTHER VIEWING: Fires in the Mirror: Crown Heights, Brooklyn and Other Identities (1992), is a one-person play by Anna Deavere Smith, composed of monologues from interviews Smith conducted with people affected by the 1991 riot.

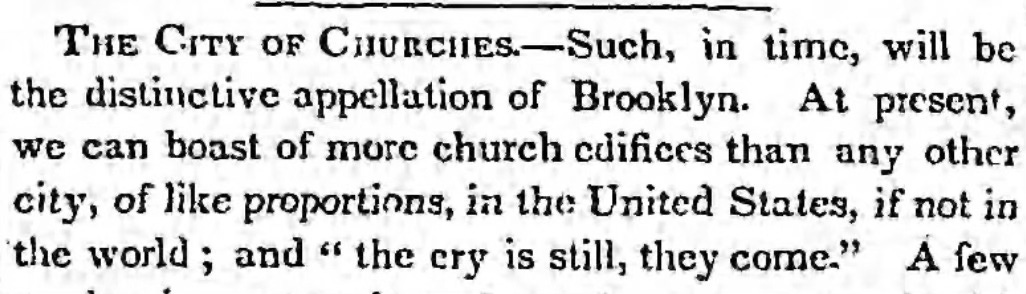

THE CITY OF CHURCHES (and synagogues, and mosques)

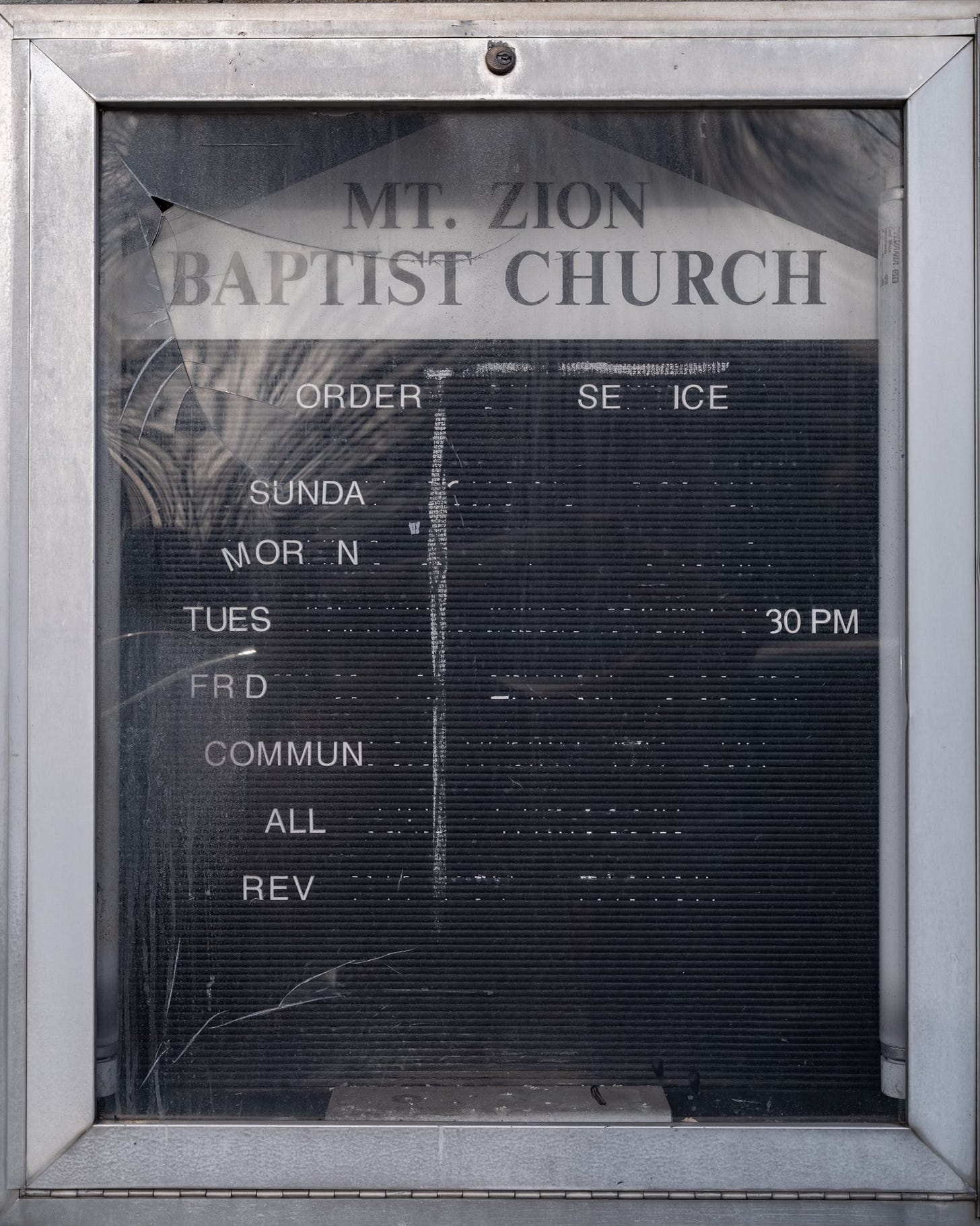

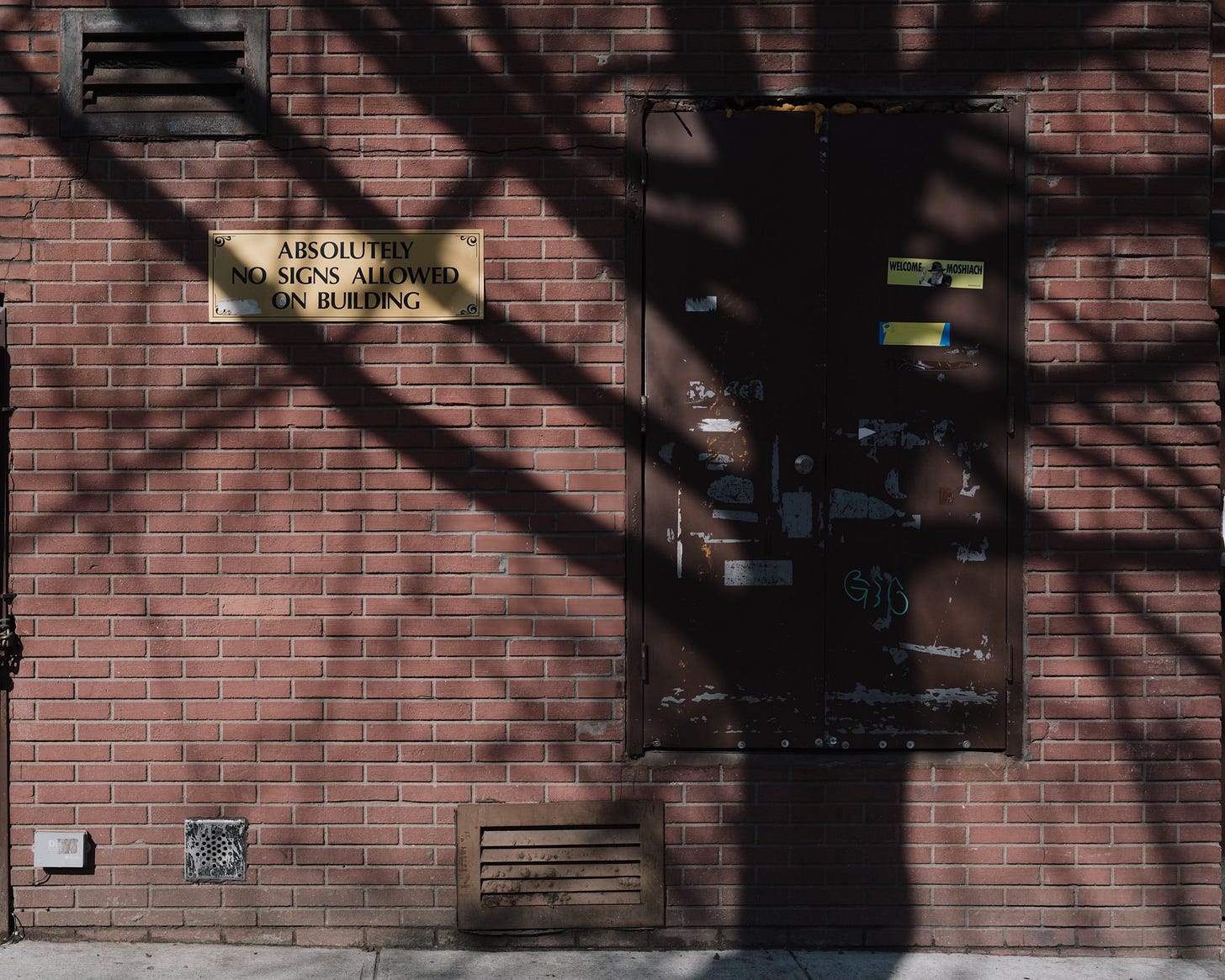

Brooklyn was first deemed the “city of Churches” by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1844 and, if Crown Heights is any indication, that designation still holds true.

Today the neighborhood has over 250 religious institutions which translates to about one religious congregation or ministry for every 480 residents of Crown Heights.2 Walking around the neighborhood, that number seems low. There are large Roman Catholic and Seventh-day Adventist churches.

There are hundreds of humble storefront churches- Evangelical, Pentecostal, and Baptist houses of worship occupying modest one story buildings or tucked into the ground floors of townhouses, sometimes right next to each other.

There are synagogues and mosques.

And my personal favorite, what famed urban explorer Matt Green dubbed churchagogues.

I’ve always been drawn to these sorts of architectural adaptations but just recently thought I would get in a little closer and focus on the details.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio features some sounds from some of Crown Height’s churches, a dance studio and various snippets from around the neighborhood’s busier thoroughfares.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHERS

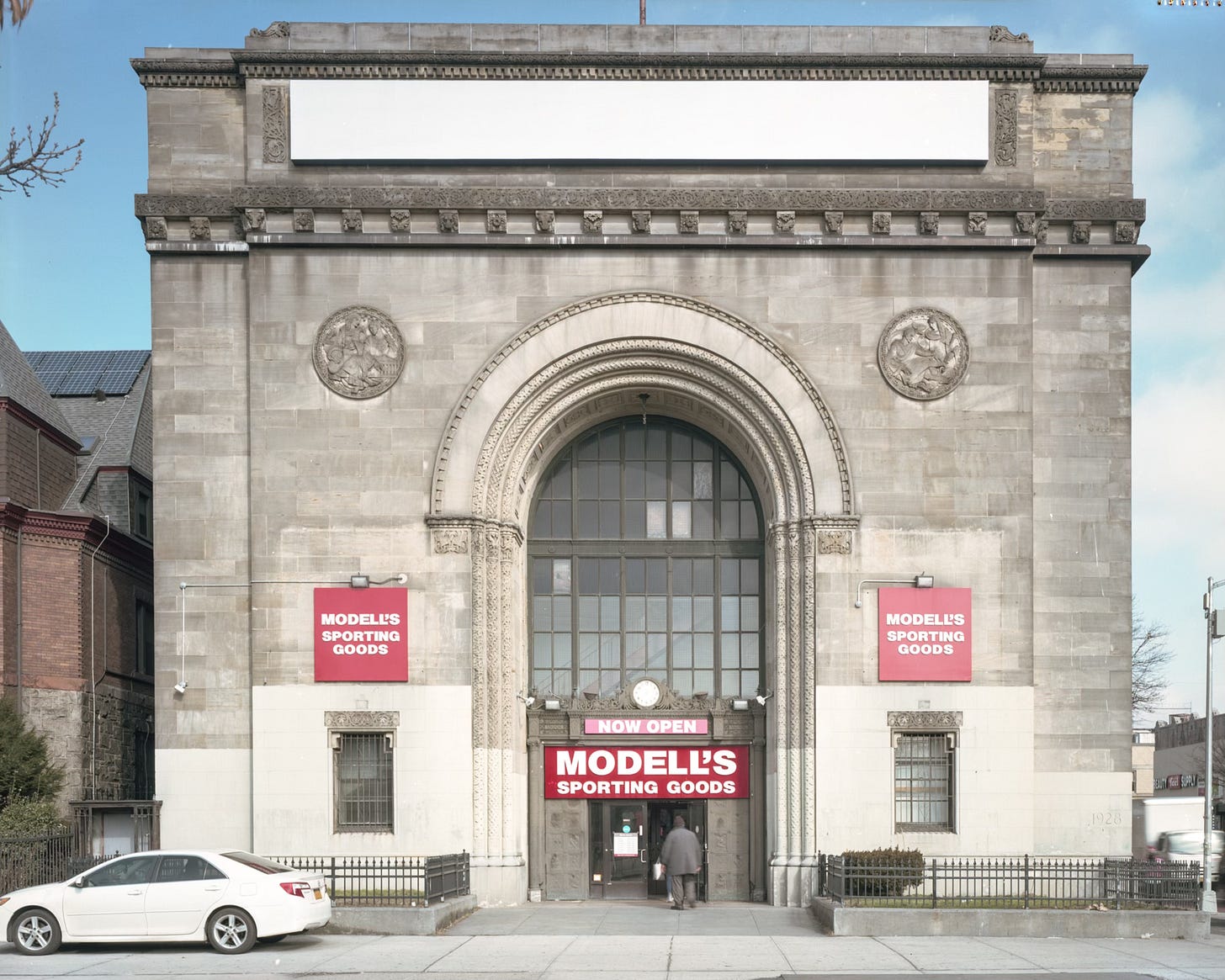

Photographers Andrea Robbins and Max Becher are a married couple, who, like Becher’s parents, Bernd and Hilla Becher, work on their project collaboratively. They say the principal theme of their work is “the transportation of place,” described as “situations in which one limited or isolated place strongly resembles another distant one.”

With that thesis in mind, the many iterations of 770 are the perfect subject.

So good!

You can see more of their work here.

ODDS AND END

Ebbets Field, home to the Brooklyn Dodgers, was built on the border of Crown Heights and Pigtown in 1912. It was demolished in 1960 and replaced by the Ebbets Field Apartments.

Here is a fantastic short interview with photographer Donal Holway describing his experience photographing the Rebbe’s 80th birthday inside 770. Donal also photographs the annual delegation of Hasidic rabbis that gather outside 770 to pose for a group picture.

A photo from my Roof to Table series of the Seeds To Feed Rooftop Farm

There is no shortage of eating options in the neighborhood, but as someone always on the lookout for a good veggie burger, I want to put in a plug for the vegetarian/vegan Nigerian takeout spot, Akara House on Nostrand Avenue. The burger patty there is made from a deep-fried mixture of puréed honey beans mixed with ginger, garlic, onion, and jalapeño, and is amazing. 5/5 stars.

https://forward.com/culture/474642/how-770-eastern-parkway-chabad-lubavitch-rebbe-schneerson-history-jewish/ McDonalds.

https://nycreligion.info/religious-riches-crown-heights-brooklyn/

I lived in Crown Heights for most of my 20s so these photos filled me with nostalgia. I particularly love your photo of the old flower shop storefront on Atlantic. I used to pop in there once in a while and the old guy behind the counter was kind and humorous. The last time I went in there he let me know he was closing the shop to retire and I was happy for him because he was so excited about it.

-"He described the female inmates as having “the eyes of wolves and brutal faces stamped all over with the unmistakable brands of vice.” Yet another example of the flowery prose of 19th century journalism. It makes me wonder what the MEN were like...

-Note to self: do more research into Nosey Kate Martin...she sounds badass...

-One thing you failed to mention was the fact that the neighborhood also lent its name to one of the more underrated funk bands of the 1970s. The Crown Heights Affair had mostly minor hits during its existence but their work set the stage for the evolution of funk into disco. My favorite of theirs is "Do It (The French Way)" which combines a great groove with a ton of humor:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTxmydFic8U