The tree-lined thoroughfare known as the Grand Concourse runs through the middle of the Bronx like a spine, stretching nearly five miles from East 138th Street to Mosholu Parkway. The neighborhood of Concourse gets its name from the 11-lane boulevard that delineates its eastern edge.

Concourse’s other borders are 153rd Street to the south, Jerome Avenue to the west, and Clarke Place to the north. Though the Grand Concourse cuts through several neighborhoods like Highbridge, Fordham, Mott Haven, Norwood, and Tremont, the roadway’s most architecturally significant buildings, including the largest collection of Art Deco buildings outside of South Beach, are concentrated within the eponymous neighborhood.

Other landmarks include the Bronx County Courthouse—a nine-story limestone monolith dominating the southern end of the neighborhood—the Bronx Museum of the Arts, with its pleated, fritted-glass facade, and Yankee Stadium, arguably the Bronx's most famous structure.

BOULEVARD OF DREAMS

After its annexation into New York City in 1874, the Bronx's population exploded from around 40,000 to over one million by 1930.

Soon after the borough was incorporated into the city, public demand for green space prompted the New York State Legislature to approve the purchase of approximately 4,000 acres of parkland, primarily in the borough’s northern section. However, much of this land remained largely inaccessible due to the poor condition of existing roads—described at the time as “elongated mud ponds, punctured here and there with turbid pools of stagnant water and malodorous filth.”

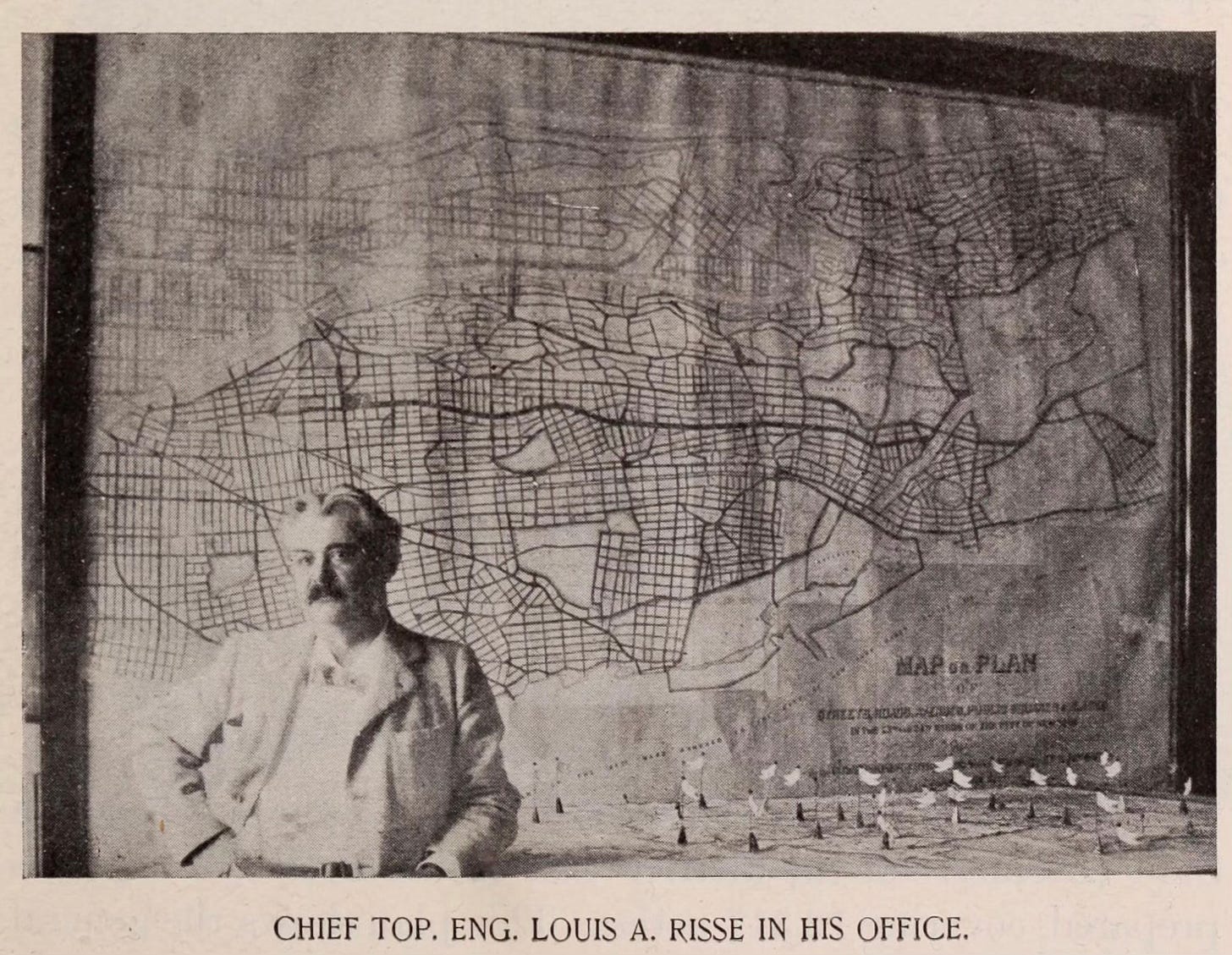

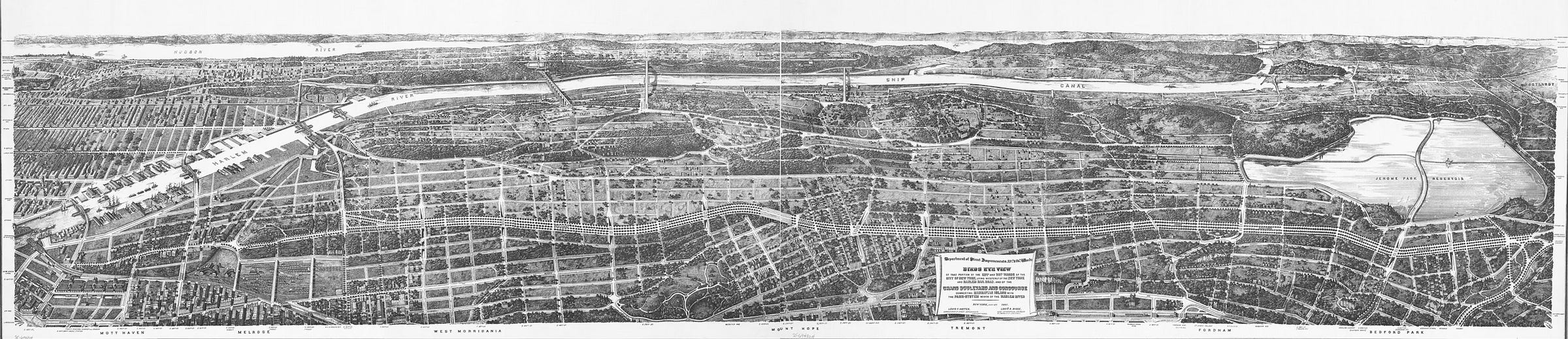

In response, the city created the Department of Street Improvements, which was tasked with developing a new street grid to improve access to the parks and the rest of the borough. The centerpiece of this effort was the Grand Boulevard and Concourse, which would become the Bronx’s most famous thoroughfare.

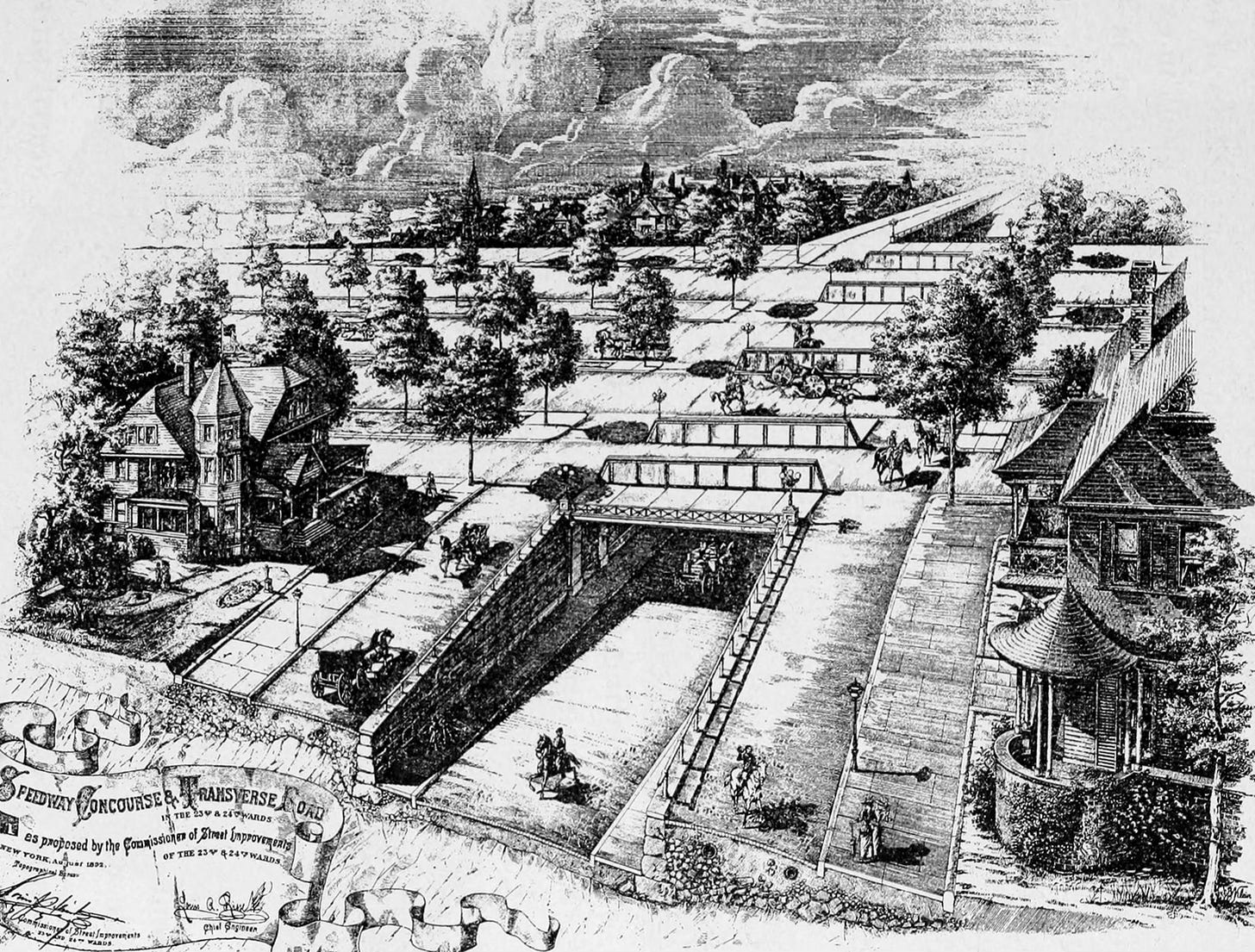

The road was conceived of by French-born engineer Louis Aloys Risse, whose design reflects inspiration from the Champs-Élysées and the work of Olmsted and Vaux in Central Park and Eastern Parkway. Risse had also been inspired by his weekends hunting grouse in Bathgate Woods, an unspoiled stretch of wilderness in what is now Crotona Park. The woods sat atop the easternmost of three ridges running north to south through the Bronx—the very ridge along which Risse would eventually lay out the Grand Concourse.

Risse designed the thoroughfare as “a drive of extraordinary delightfulness and practical convenience,” separating cyclists, pedestrians, and trolleys with tree-lined medians and burying the intersecting cross streets.

By the time it had finally been built in 1909, the horse-drawn carriages Risse had depicted in his sketches had largely been replaced by Model Ts.

Soon after the boulevard’s completion, residential construction in the neighborhood surged. Several well appointed apartment buildings sprang up, with the most desirable residences lining the boulevard. The expansion accelerated with the opening of the Bronx–Concourse subway line, and by 1939, the Grand Concourse had earned a reputation as “the Park Avenue of the middle-class Bronx.”

Most new residents were Jewish families moving north from Manhattan’s overcrowded tenements in search of more space and better living conditions. The new buildings, many with doormen, had modern amenities like elevators and corner windows. As Constance Rosenblum writes in Boulevard of Dreams, the Grand Concourse became “the lodestone by which distances were measured.” A family’s true mark of success was not just moving to the Bronx—it was how many blocks they lived from the Grand Concourse.

FREEDMAN

Amidst this sea of five- and six-story buildings, the Andrew Freedman Home, modeled after the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, is an architectural anomaly.

Andrew Freedman was a self-made millionaire with deep ties to the power brokers and grifters of Tammany Hall. After the Panic of 1907, Freedman had his come to Jesus moment. The possibility of a life without polished silverware, plush carpets, and genteel conversation terrified him, and he decided he must build a retirement home for a very niche demographic: formerly wealthy individuals who had lost their fortunes. “The fate of cultured persons who had lost their money,” a friend of Freedman said, “was the saddest thing in his life.”

Built in 1924 in the style of an Italian Renaissance palazzo, the four-story yellow limestone building had an oak-paneled library, card and billiard rooms, multiple fireplaces, and a spacious dining room decorated with chinoiserie. The ceilings were high, the carpets deep, and the couches overstuffed. Formal dress was required for dinner.

Residents paid no rent but were expected to maintain a certain standard of living. Admission required an “income sufficient for their clothes, cigars, bridge lessons, movies, and enough capital for burial expenses.”

By the 1960s, the home’s endowment began to run out, and in 1982, the building was sold to the Mid-Bronx Senior Citizen Council and turned into a residence for the elderly, none of whom were required to show proof of their former fortunes.

COCKING A SNOOK

Before he became famous for protecting the formerly rich from the indignities of poverty, Andrew Freedman was best known for his turbulent tenure as owner of the New York Giants baseball team. From 1895 to 1902, he clashed constantly with players, feuded with league officials, and was repeatedly urged to sell the team. The New York World once described him as having “an astonishing faculty for making enemies.”

One of his most infamous conflicts was with Giants ace Amos Rusie, a pitcher whose fastball’s velocity was matched only by its inaccuracy. Rusie still holds the all-time single-season record for walks, but when he found the strike zone—reportedly with a pitch exceeding 95 mph—he was nearly unhittable.

After one of his errant fastballs struck shortstop Hughie Jennings in the head, leaving him in a four-day coma, the league voted to move the pitching mound back ten feet.

Rusie may have been having trouble with his pitch location since he had sat out the entire previous season. During a contract dispute, Rusie thumbed his nose at Freedman in public. At the time, thumbing your nose (or “cocking a snook” ) was considered a particularly offensive gesture, and the enraged Freedman fined his ace $200. Rusie sat out the season in protest. As the standoff dragged on, the league president declared Freedman “an impossibility in baseball” and demanded he leave the sport.

Freedman refused and instead bought a controlling stake in the American League’s Baltimore Orioles and gutted the team, releasing its best players—many of whom quickly signed with the Giants. Left in shambles, the Orioles were so short on players that they had to forfeit their first game of the season. After finishing the season with the league’s worst record and lowest attendance, the team relocated to New York City in 1902. Eleven years later, they were renamed the Yankees.

THE HOUSE THAT RUTH BUILT

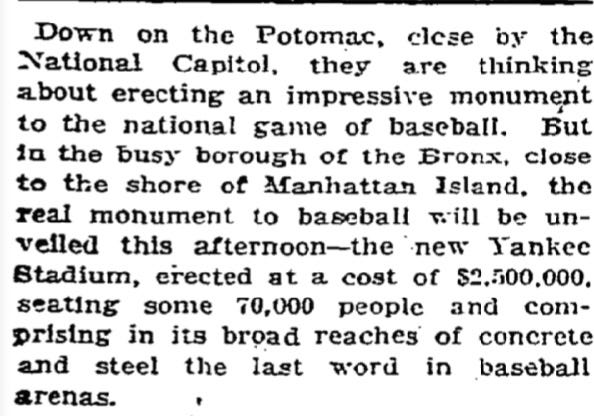

Ironically, the Yankees would spend a decade sharing a stadium with Freedman’s former team, the New York Giants. After the addition of Babe Ruth to the roster in 1920, the Yanks were soon outselling the Giants, and co-owners Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston and Jacob Ruppert (of Yorkville fame) decided it was time to build their own ballfield.

On April 18, 1923, the Bronx Bombers played their inaugural game on 161st Street by the Harlem River in the newly built Yankee Stadium.

A reported 74,000 (later amended to 62,200) fans packed the stands, while another 25,000 were stranded outside. Governor Al Smith threw out the opening pitch.

Those lucky enough to get in witnessed the Great Bambino launch a line-drive home run into the right-field bleachers in the third inning, propelling the Yankees to a 4-1 victory. That season, they went on to win their first World Series.

The stadium, which was constructed on top of a lumberyard once owned by William Waldorf Astor, took less than a year to complete and cost $2.4 million. By comparison, the new Yankee Stadium, which opened in 2009, cost over $2.3 billion. Even adjusting for inflation the cost of the first stadium was just 1.5% of its modern successor.

While the old stadium lacked a state-of-the-art digital scoreboard and Budweiser Party Decks, it was revolutionary for its time. Building the first three-tiered ballpark in the country required over 3,400 tons of structural steel and 30,000 cubic yards of Thomas Edison’s patented cement. The field’s 116,000 square feet of sod was sourced from a secret location in Long Island and laid over an intricate network of pipes and drains to maintain the field’s pristine conditions. The soil beneath was sifted through silk cloth to remove any rocks or pebbles.

During its 85-year run, Yankee Stadium hosted some of the greatest teams and games in baseball history. It was also where the Baltimore Colts defeated the New York Giants in "The Greatest Game Ever Played,” and where Joe Louis knocked out the German boxer Max Schmeling in what has been called one of the most politically and culturally significant sporting events of the 20th century.

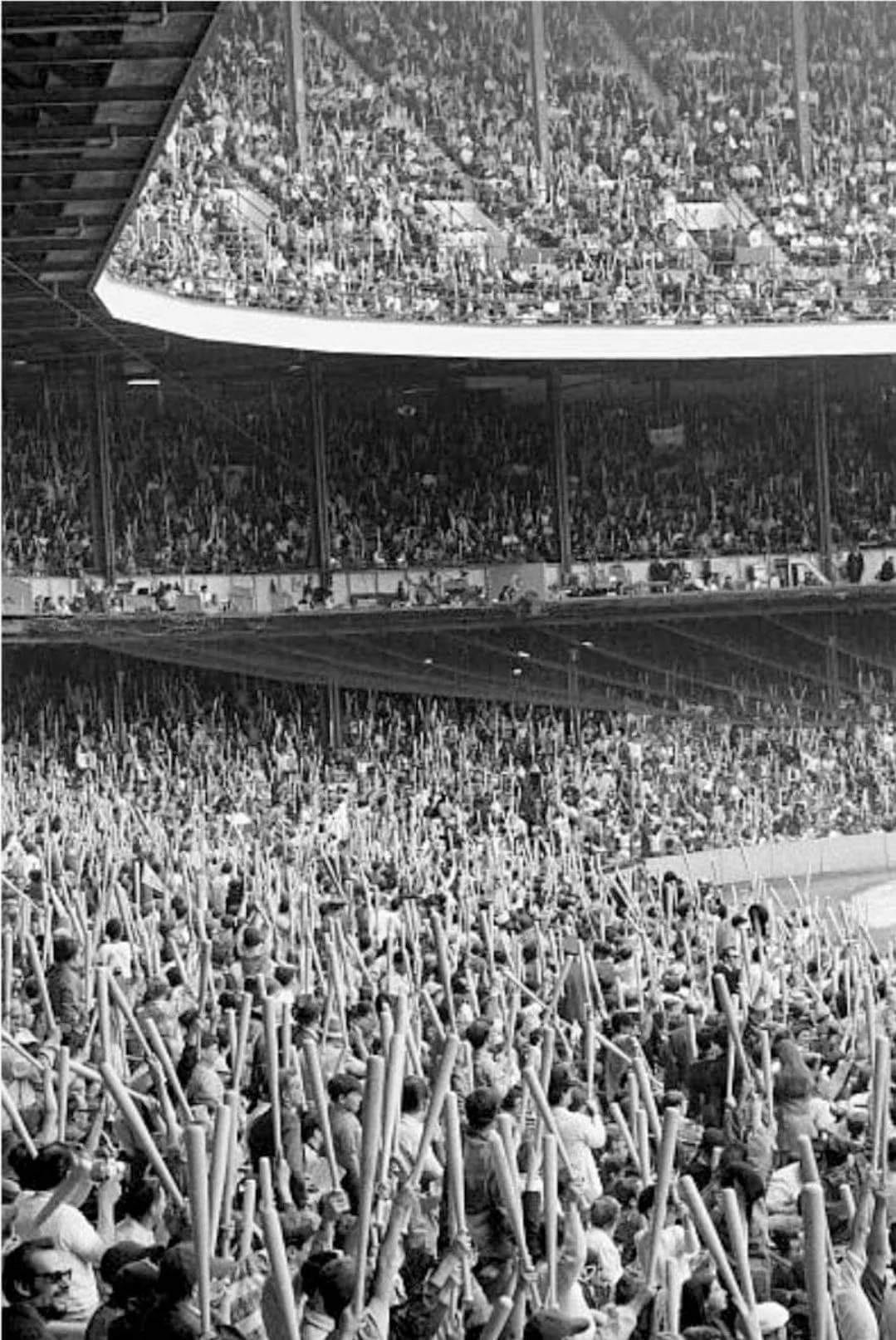

Artists like the Isley Brothers, Pink Floyd, and James Brown put on shows in the stadium. At a 1973 concert by salsa supergroup the Fania All Stars, fans got so worked up during what must have been an incendiary conga duel that they stormed the field, sending the band members running to the dugouts for cover.

Three popes—Paul VI, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI—each delivered sermons in the stadium. It truly was the heart of the Bronx until the last Yankee game was played there on September 21, 2008. One year later, and one block north, the new Yankee Stadium opened for business. That same year, the Yankees would win another World Series.

NUTS

I figured that if I was writing about a neighborhood whose identity is so inextricably tied to the stadium at its center, I should probably attend a game, so I convinced my friend and his son to meet for the Yankees’ third game of the season against the Milwaukee Brewers.

Expectations were running high following on the heels of an epic 9-homer, 20-run game the day before (which some attribute to the team's redesigned torpedo bats). I boarded the 4 train at Canal Street and luckily managed to grab a seat. At every stop, more and more Yankees fans piled in—a growing sea of pinstripes in the tight quarters of the train car.

When the doors finally slid open at 161st Street, disgorging a tumult of hooting fans, I breathed a sigh of relief.

My last Yankee game was in the 1980s, which happened to be Bat Day when everyone in the stadium under 14 got to come home with a miniature version of a Yankees bat. When Bat Day first started in 1965, the stadium would give away full-sized bats, which, call me crazy, seems like a pretty terrible idea.

The weather was brutal for a springtime baseball game, especially considering it had been a balmy 80 degrees the day before. Unfortunately, it wasn’t Down Parka Day.

The cold fog blowing in over center field didn’t seem to dampen the enthusiasm of the bleacher creatures, who were maniacally chanting Aaron Judge’s name before the MVP had even taken the field.

In an effort to fortify themselves against the cold, the growing crowd was enthusiastically gobbling down a panoply of classic ballpark treats. There were buckets of fried chicken. Giant cups of soda. Giant cups of soda topped with buckets of fried chicken because who doesn’t want to stick their nose in a mound of hot chicken tenders while swigging on a Diet Pepsi? I later learned this device is called the Grub Tub, a creation that some people have called “the greatest invention since man discovered fire."

There were flat rectangular boxes of popcorn. Miniature Yankee helmets filled with nachos. Soft serve containers stuffed with piles of glistening meat of indeterminate origin. And, of course, the ubiquitous stadium dog—a pinkish, glossy wiener swaddled in a steaming bun.

Predictably, there was not a single vegan option to be found in this veritable smorgasbord of gameday fare. Just as I had begun to resign myself to a liquid lunch, my friend—who had just returned from the concession stand, hot dog in hand—tossed a giant bag of Brazzini peanuts into my lap. A classic snack for America’s pastime, and just what the doctor ordered.

As soon as the peanuts landed, the woman sitting next to me abruptly stood up, grabbed her coat and moved two seats down.

“I have a peanut allergy,” she informed me, “but it’s not airborne, it should probably be okay.”

The interaction triggered a Larry David-esque crisis of conscience wherein I had to weigh the possibility of potentially putting someone into anaphylactic shock vs. my sudden intense hankering for a handful of goobers. While I had to question the wisdom of attending an event so closely associated with a food that could kill you that they sing about it every seventh inning, I decided to play it safe and keep the nuts in the bag.

The Yankees would go on to win the game 12-3, though we left in the 8th inning so I could get something to eat.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

Last week, while walking around Concourse with my recorder on, I found myself next to a woman having an animated phone conversation about drug dealing. At first, I thought this was some sort of intervention, but it soon became clear she was actually delivering a searing critique of closed minded TV-watching habits and an unflinching treatise on the state of modern prestige television. Someone get this woman a podcast. This week’s recording also includes sounds from the ballgame.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

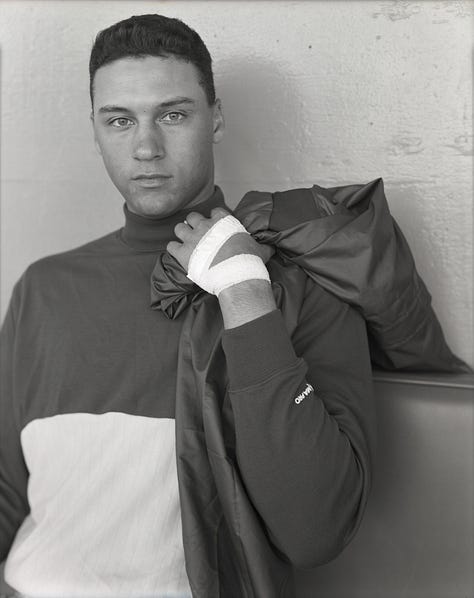

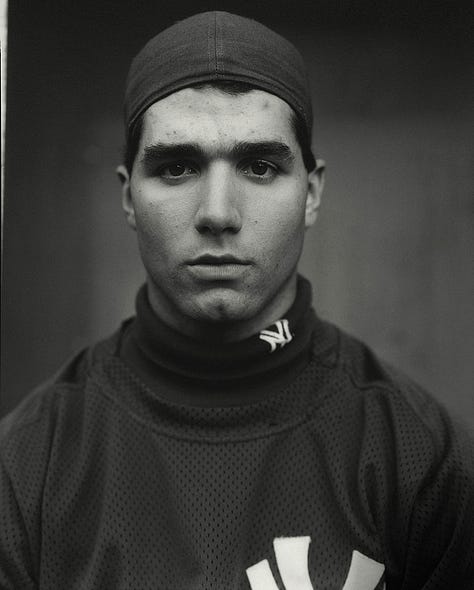

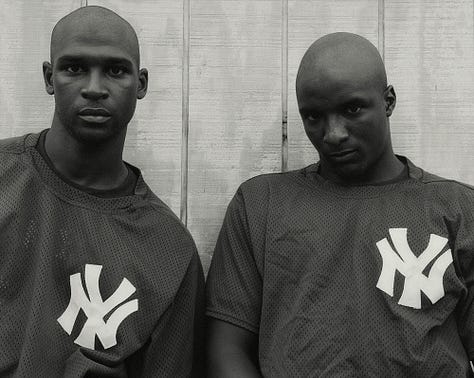

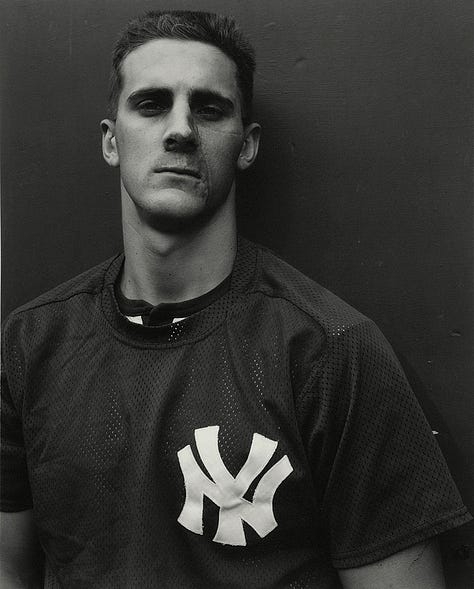

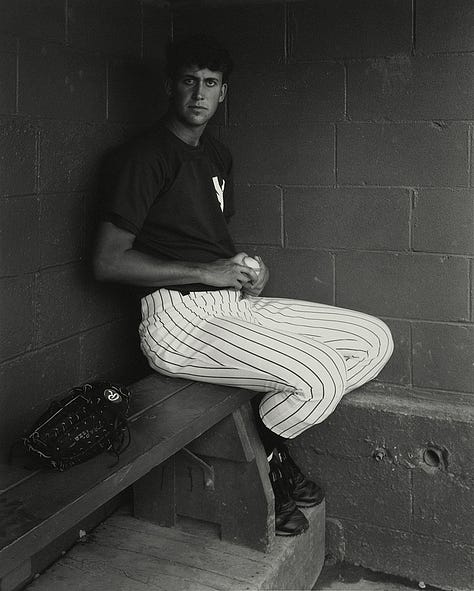

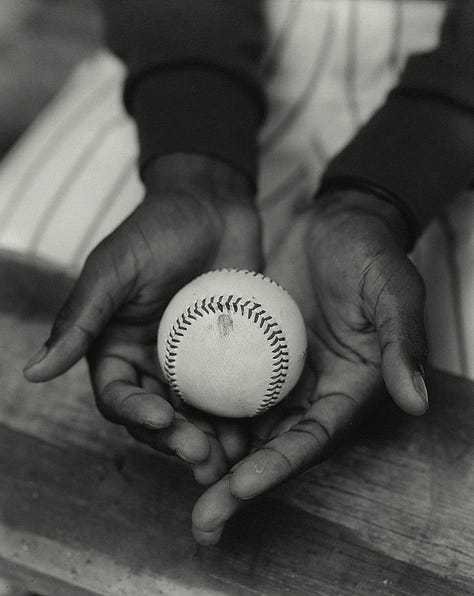

I featured Andrea Modica’s singular images when I covered Bay Ridge last year. I thought of her again for this week’s feature as her first monograph, Minor League, has a connection to some of the neighborhood’s most famous residents.

While living upstate in the early 90s, Modica attended a Oneonta Yankees game, a minor league “Short Season A” affiliate of the New York Yankees. The game inspired her to start taking pictures of the players. Using her 8x10 camera, she created portraits of the minor leaguers, some of whom would go on to become South Bronx legends, including Jorge Posada and Derek Jeter. Minor League, published in 1993, features reproductions of several of Modica’s beautiful palladium prints from this series.

You can see more of Andrea’s work on her website

ODDS AND END

While Lous Risse did the dirty work of designing the Grand Concourse, his boss, Louis J. Heintzs, the first commissioner of Street Improvement, is the one who got a statue. Over the years, the statue, which is in Concourse’s Joyce Kilmer Park, has suffered various indignities, the worst being the decapitation and subsequent theft of the head of Fame, the allegorical figure at the monument’s base. Here is an article that tells the story of the struggle to make an accurate replacement head in the absence of any documentation: In the Bronx, A Face Lost in Time.

Here is a video of Yankee organist Ed Alstrom condensing nine innings of music into fifteen minutes.

Did you know that Cracker Jacks offers a caffeinated line of snacks called Cracker Jack’D power bites?

Today is the last day to support Valery Rizzo’s Kickstarter campaign for her upcoming Wonderland Brooklyn 2007 - 2023, a photography book about Brooklyn made entirely with plastic toy cameras.

I would be negligent if I didn’t include Chris Farley’s portrayal of Rudy Guliani’s son, Andrew, enjoying a Yankee game.

I am so sorry to be this person, but the sod was sourced from a secret location *on* Long Island, not *in* Long Island. I grew up on Long Island and I lived in Manorville. I don't know why it's like this, but it is.

Also the photo of the traffic cone in the puffer jacket somehow seems like the most Bronx thing to exist, like it's only missing some disembodied Timbs nearby.

Thanks for saving me some money and time. I had been thinking of attending a ball game with my son when I finally make it back to NYC. However, as a vegetarian with a son who has severe anaphylaxis, that’s probably not going to happen.