In Thomas Wolfe’s 1937 short story Only the Dead Know Brooklyn, a subway rider asks for directions to “Eighteen’ Avenue an’ Seventy-sevent’ Street” in “Bensenhoist.”

When the narrator asks him why he is going there, the rider answers:

I like duh sound of duh name—Bensenhoist, y’know—so I t’ought I’d go out an’ have a look at it.… I like to go out an’ take a look at places wit nice names like dat. I like to go out an’ look at all kinds of places.

As aggravating as I find Wolfe's Brooklyn patois, I can't help but see some parallels between myself and the character the narrator calls 'duh big guy,' who wanders the city, guided by curiosity and "a big map of duh whole goddam place." And, like the 'duh big guy,' I too found myself in Bensonhurst this week, which, for those of you keeping track, is the ninety-first neighborhood I have documented to date.

Between catching the flu last week and this week's arctic temperatures, I briefly considered taking a hiatus. But with over 200 neighborhoods left, I decided to stay the course. After all, if this guy can handle the cold, what's my excuse?

Besides Wolfe’s short story, Bensonhurst has also served as the backdrop for several films and TV shows like The Honeymooners, The French Connection, Saturday Night Fever and others I’m sure I’m leaving out.

Outside of popular culture, the neighborhood is probably most associated with the 1989 murder of Yusuf Hawkins. At the time, Bensonhurst was 80 percent Italian. Today, it has the second-largest immigrant population in New York City, with residents from China, Albania, Russia, Egypt, Georgia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Mexico mingling in its streets.

Bensonhurst shares a border with Bath Beach, and the two were once considered part of the same neighborhood. Today, the overhead tracks along 86th Street serve as a clear dividing line between the neighborhoods. 14th Avenue, 60th Street, and Bay Parkway/Avenue P make up Bensonhurst’s other borders.

BY THE SEA

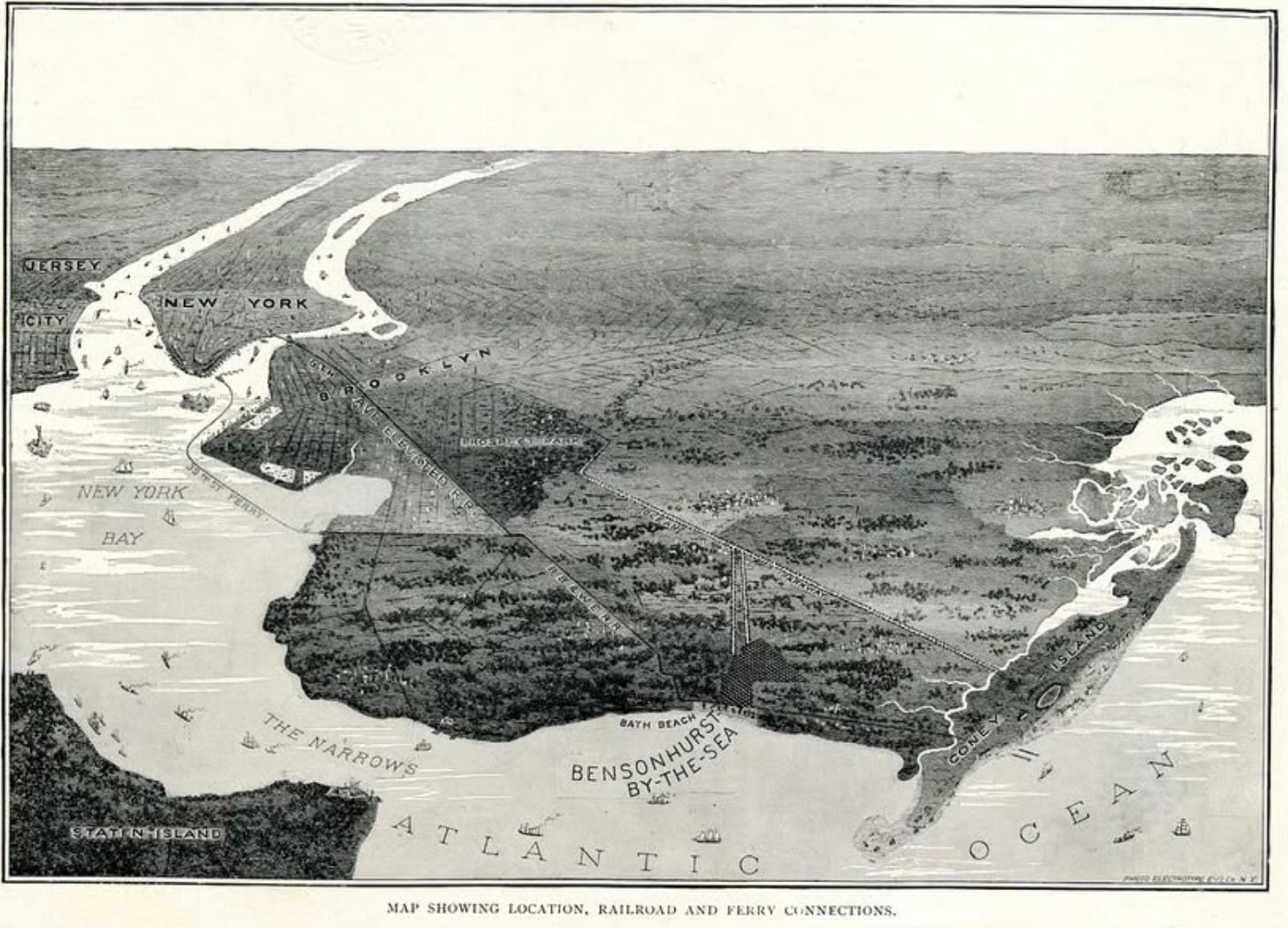

Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, Bay Ridge, Borough Park, Dyker Heights, and Fort Hamilton were all once part of New Utrecht, one of Brooklyn’s six original towns.

In 1652, Dutch surveyor Cornelius van Werckhoven purchased the land from the Canarsies in exchange for six shirts, two pairs of shoes, six chisels, six knives, and six cans. When he died two years later, his children's tutor, Jacques Cortelyou, took over. He divided the land into twenty-one plots, naming it New Utrecht, after the Dutch city. Cortelyou would later create the first detailed map of New York in 1660, the Castello Plan.

New Utrecht remained mostly farmland until the late nineteenth century when developer James Lynch convinced the Benson family, by then the predominant landowners in the area, that they'd make more money selling land than cabbages. Soon, Lynch had amassed enough property to build what he modestly called "the most perfectly developed suburb ever laid out in New York."

If you read last week's newsletter, you may remember that Arverne incorporated as Arverne-by-the-Sea in 1895. Apparently, hyphenated toponyms were all the rage because Lynch named his development Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea. Maybe those dashes helped confer a sense of exclusivity—little typographical gates keeping out those who couldn't afford the $3,000 starting price, which guaranteed that "all kinds of nuisances [were] prohibited."

Of course, this was still Brooklyn, and no amount of linguistic frippery could keep the trouble at bay.

A NIGHTLY LIGHTING OF POTATO PATCHES

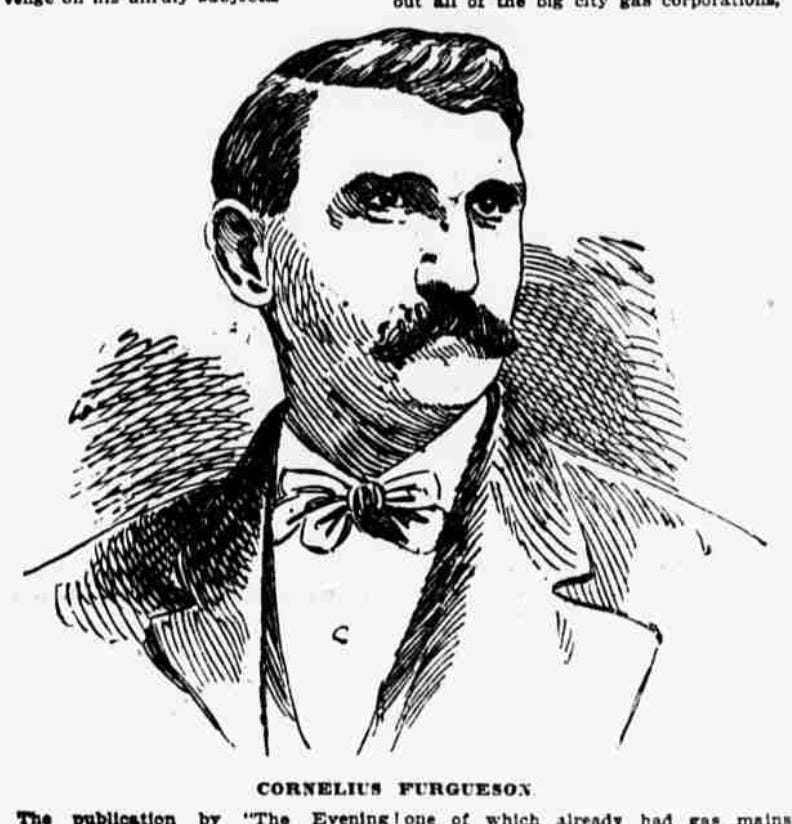

While James Lynch was busy building his utopian suburb, New Utrecht’s political boss, Cornelius Furgueson, was making sure you could see it from space.

Furgueson started out as a journeyman bricklayer before being elected to the Kings County Board of Supervisors, a position that opened the door to all sorts of fraud. Over time, the former bricklayer accumulated an impressive number of titles including State Shore Inspector, County Supervisor of New Utrecht, President of the New Utrecht Board of Health, Chief of the New Utrecht Police, Chairman of the New Utrecht Street Flagging Committee, Chairman of the New Utrecht Sewer Committee, and Treasurer of the New Utrecht Home for Inebriates.

Furgueson's most brilliant scheme came in the form of a sweetheart deal between the New Utrecht Gas and Illuminating Company and the New Utrecht Board of Improvements, a board that, unsurprisingly, he controlled. Furgueson installed 4,000 gas lamps—one per three residents—costing the town $28 each per year.

An 1894 New York Times article shed some light on the grift:

Long rows of lamps extend for miles in every direction. They are not confined to the paved streets. They are not scattered along inhabited thoroughfares. They extend through lonely roads and secluded lanes, bounded by fertile farms or neglected lots.

At this season of the year, their rays fall upon banks of snow and mud, untraversed by wheel or runner. In summer, they shine on rows of cabbages, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, and other garden crops. There is no more need for hundreds of these lamps than there would be for a refrigerator at the North Pole or a self-feeding furnace in Sheol.”

Not content with merely illuminating the endless cabbage fields, Furgueson also decided to protect them from fire by passing the Fire Hydrant Act, which resulted in a fifty-year contract with the water corporation.

The placement of hydrants was left to "the discretion of the town board." As one observer put it, "The people of the town are expecting to see a hydrant alongside every one of the 4,000 lampposts."

However, the promised fire hydrant bonanza was slow to materialize. On an early April morning in 1895, a fire broke out at a house in town. The first company to arrive attached their hose to "the only hydrant in the vicinity," only to find that their hose was too short. The second company arrived soon after but refused to share their equipment. J. Harry Adams stood hopelessly by as his house, brilliantly illuminated by the dozens of street lights surrounding it, burned to the ground.

ALL IN

Another one of Bensonhurst's more memorable stories from this time involves William Crane, the community choirmaster and Sunday School Superintendent of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Holy Spirit.

On a September evening in 1896, Crane dismissed choir practice half an hour early, then rushed to the Benson Hotel, where a one-dollar ante poker match was underway. The game was overseen by Edward Stowell, who had a side business managing a traveling acrobatic troupe called the Rickford Brothers.

As the night wore on, the pot reached $30, and Crane went all in. His only remaining opponent was Forest Seabury, a champion diver in town for a local exhibition. When Seabury claimed the pot without showing his winning hand, Crane objected. The diver responded with a punch to Crane's head, and before the choirmaster could recover, Stowell shoved Seabury aside and began enthusiastically banging Crane's head against the floor.

Though newspapers reported Crane had fractured his skull and was near death, he recovered within days, insisting he'd been attacked simply for suggesting they play with matches instead of money.

A follow-up article cast doubt on his innocence:

He says, possibly with a view to the retention of his choirmastership, that it was his virtuous limitation of the game to matches which excited the base passions of the desperate gamesters among whom he fell, insomuch that they fell upon him, inflicted severe contusions, and knocked one of his teeth out. The gamesters, on the other hand, allege that they hammered him because he attempted to take unlawful possession of a jackpot and to defend his claim by drawing a pistol.

I was never able to find out what became of William Crane, but on December 31st, just one day after being thrown from a runaway sleigh, Edward Stowell was fined $25 for nearly killing the choirmaster.

BENSONHURST-AL-MARE

Rampant corruption and gambling choirmasters aside, for many years Bensonhurst's seaside location and relative isolation made it the perfect playground for New York City's aristocracy, who gathered at exclusive clubs to race yachts and play cricket.

When Brooklyn was incorporated into New York City in 1898, Bensonhurst's population was a modest 10,000 people. Everything changed with the arrival of the Fourth Avenue Subway line. With a manageable commute from South Brooklyn to Manhattan, the area opened up and the gates came down. Bensonhurst lost its "by-the-sea" suffix and gained tens of thousands of new residents. By 1930, the population had ballooned to 150,000.

This first wave of new residents, mostly Jewish and Italian immigrants, came to escape the overcrowded tenements of Manhattan's Lower East Side. The 1940s and 1950s brought an even larger influx of Italian immigrants, many fleeing the harsh conditions of Sicily's sulfur mines for the promise of a better life in Brooklyn. These newcomers would profoundly shape Bensonhurst's cultural identity.

By 1980, Bensonhurst had become one of New York's most distinctly Italian-American neighborhoods, with a population that was 93 percent white and 80 percent Italian. The cricket grounds and regattas of the previous century had given way to espresso bars, social clubs, and family-run businesses that would define the area for generations to come.

YUSUF HAWKINS

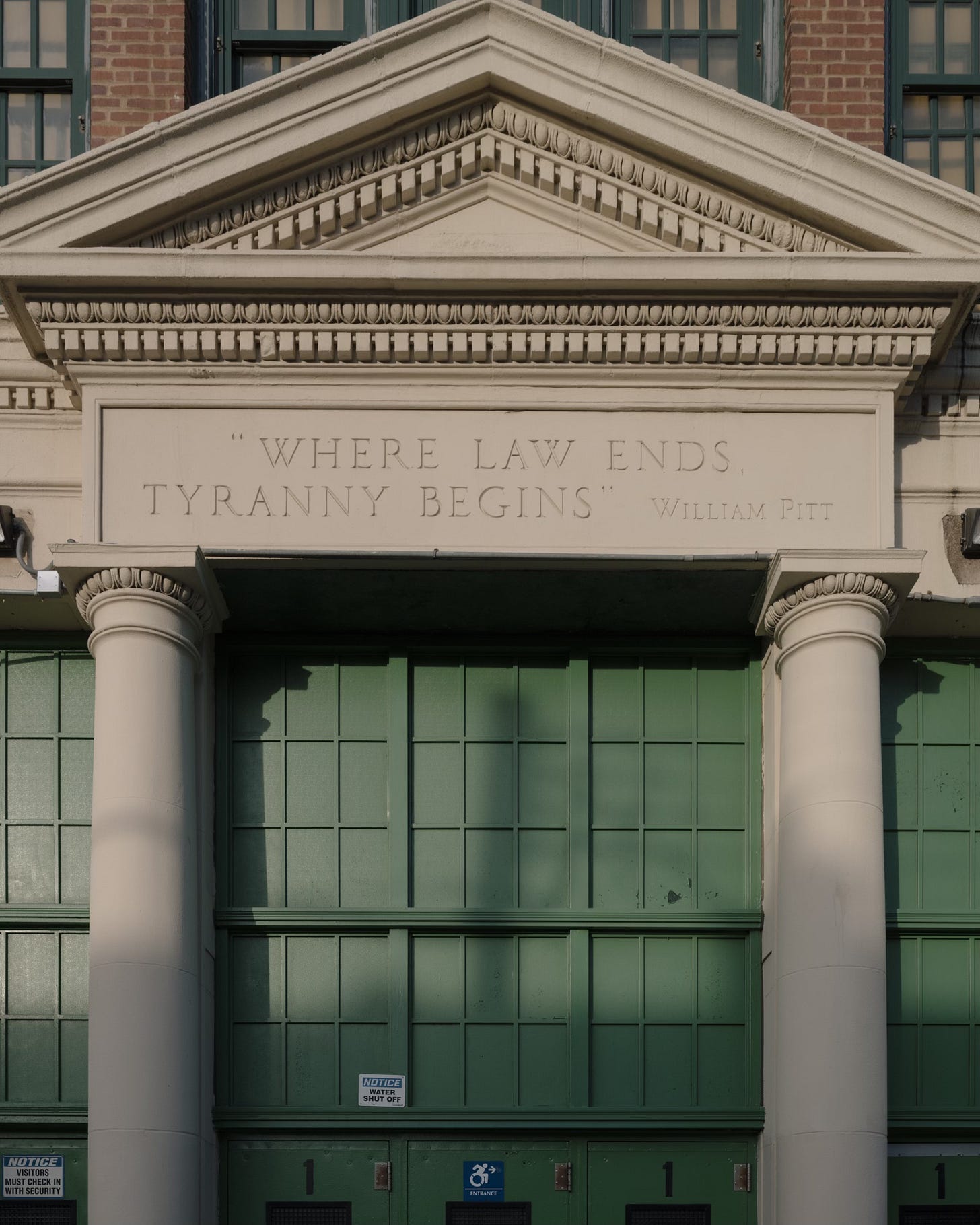

In the 1980s, New York City was embroiled in a series of incidents that exposed the deep racial tensions simmering beneath the surface of America's largest city. As New York Times reporter Cory Kilgannon would later observe, it was "a brutal period of division and violence in a city roiled by racial strife and intolerance."

The decade was marked by a slew of racially charged incidents that shook the city. In 1982, Willie Turks, a Black transit worker, was beaten to death by a white mob in Gravesend, Brooklyn, while simply trying to go home from work. Two years later, Bernard Goetz, a white man, shot four Black teenagers on a Manhattan subway, claiming self-defense. In 1986, Michael Griffith, a 23-year-old Black man, died after being chased by a white mob onto the Belt Parkway in Howard Beach, Queens.

Perhaps the most well-known incident was the 1989 Central Park Jogger case, a flashpoint that crystallized the city's racial tensions. Five teenagers were arrested for allegedly assaulting and raping a white woman jogging in Central Park.

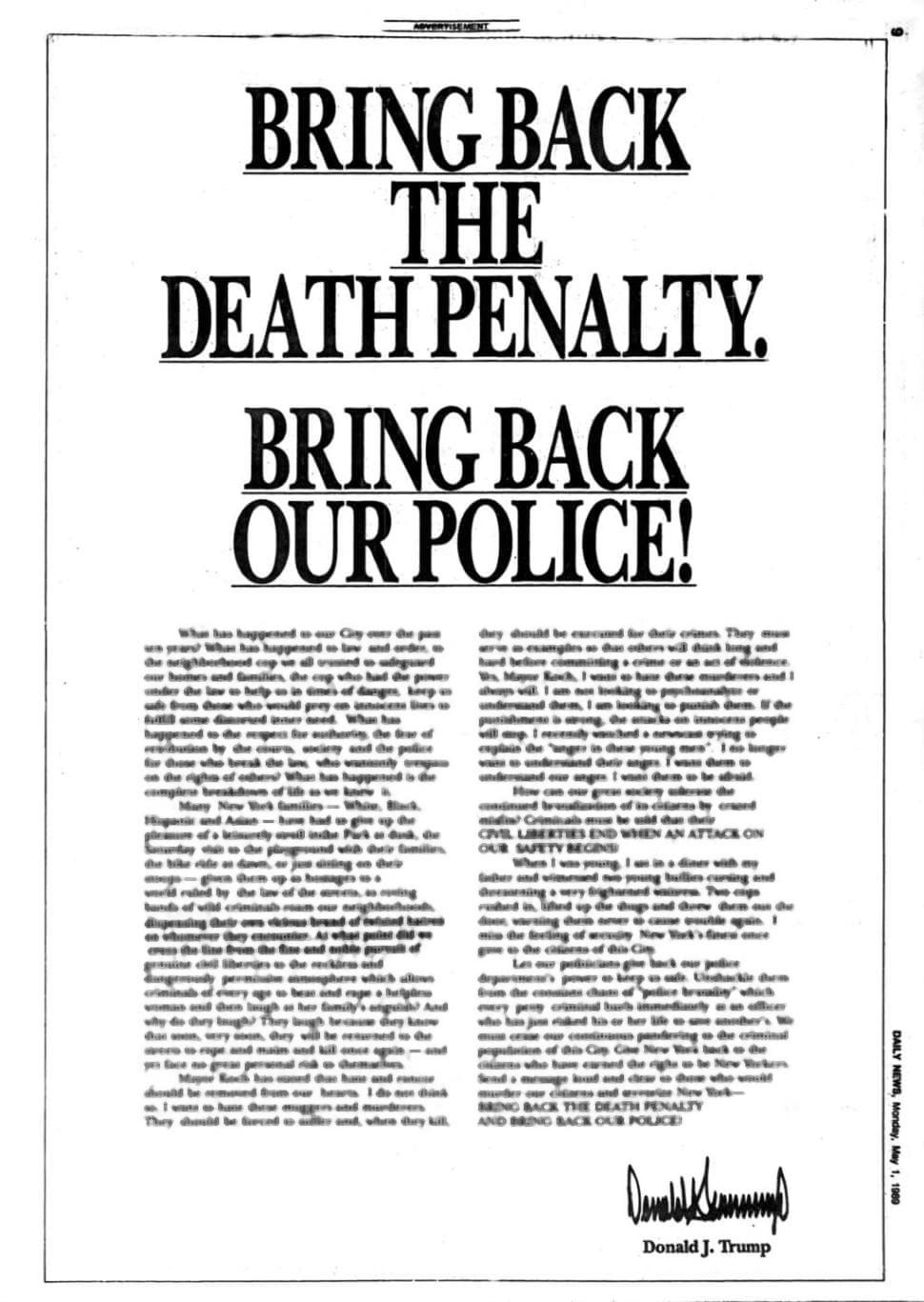

The incident prompted Donald Trump, demonstrating an uncanny ability to be on the wrong side of history, to take out a full-page ad in all four of the city’s major newspapers, calling for the reinstatement of the death penalty. Trump goes on to ask, “How can our great society tolerate the continued brutalization of its citizens by crazed misfits?”

Good question.

In 2001, all five men were exonerated after another man confessed to the crime.

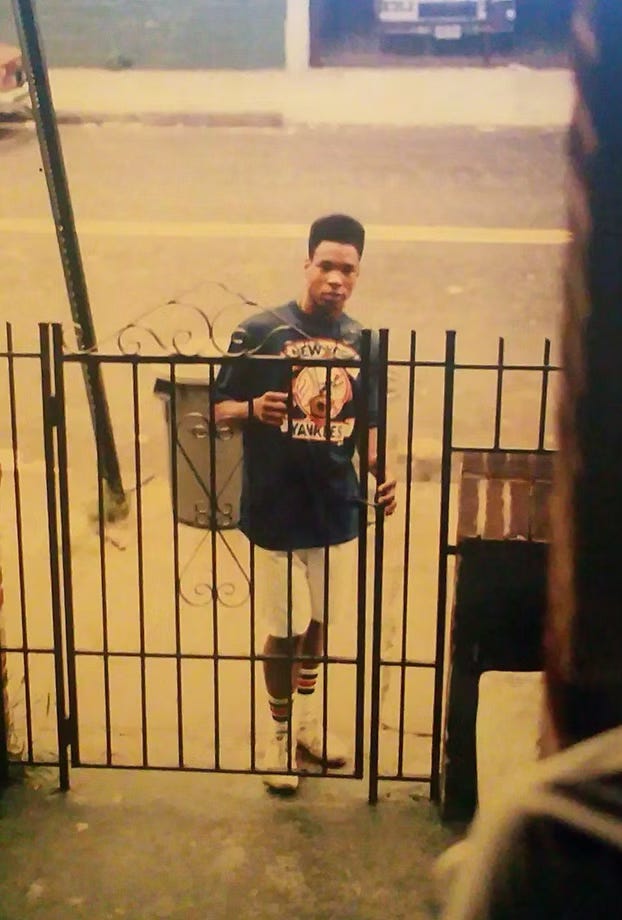

Just months later, on August 23, 1989, Yusuf Hawkins, a 16-year-old Black teenager from East New York, went to Bensonhurst with three friends to check out a used car.

Unbeknownst to them, a local girl had recently "antagonized" her ex-boyfriend, Keith Mondello, by telling him she had invited some of her Black friends to her birthday party. When Hawkins and his friends arrived, a mob of baseball bat-wielding local teenagers—led by Mondello—attacked.

Joseph Fama, 19, shot Hawkins four times, killing him instantly.

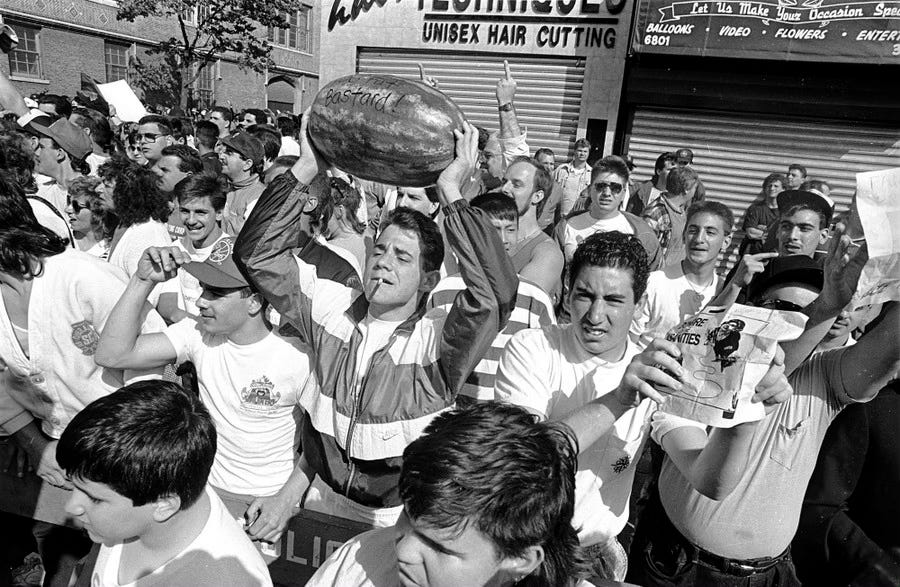

The murder ignited widespread protests, with Reverend Al Sharpton leading multiple marches through Bensonhurst. Attempts to brand the murder as not racially motivated were dispelled by the reaction of the crowds who gathered to jeer the marchers. Protesters were met with racist taunts and slurs, prompting Sharpton to remark: "I had never seen... such unrefined open hate in my life."

On January 12, 1991, while preparing to lead another march, Sharpton was stabbed in the chest by Bensonhurst resident Michael Riccardi.

Bensonhurst’s reactions to the marches made Sharpton’s earlier branding of New York as the Birmingham of the North seem far from extremist rhetoric. The murder itself received national attention at the outset, but nowhere near the type of coverage given as a result of the marches.1

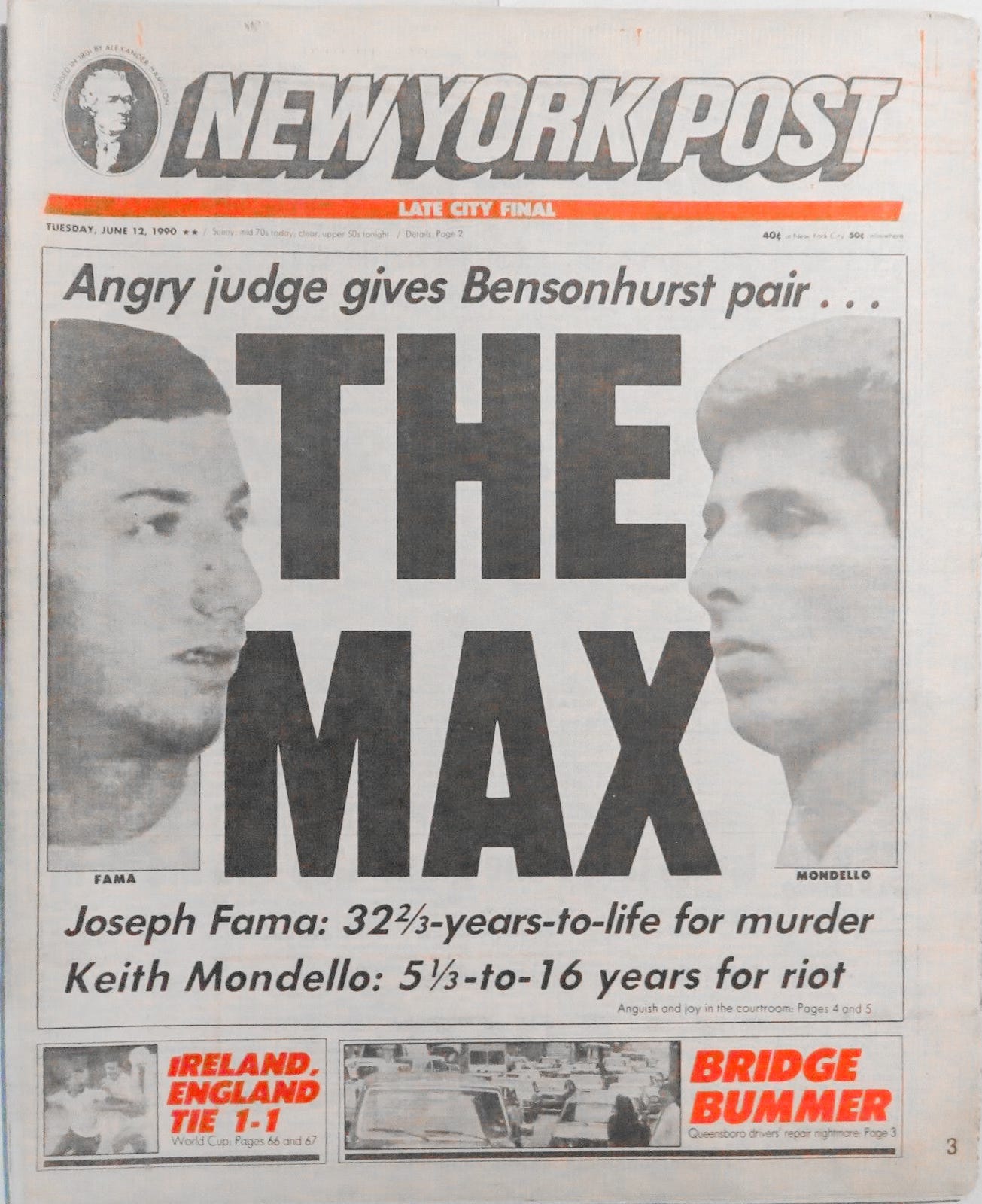

Fama was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 32 years to life in prison, while Mondello was acquitted of murder but found guilty of lesser charges. In November of last year, a Brooklyn judge granted Fama’s request for a new hearing to present evidence that he hopes will establish his innocence.

A recent HBO documentary, Storm Over Brooklyn, revisits the murder and protests surrounding Yusuf Hawkins' tragic death.

THIRD WAVE

Another wave of immigration began in the late 1980s, particularly from China and the former Soviet Union. By 2000, over half of Bensonhurst's residents were foreign-born, and by 2013, the neighborhood had the second-highest concentration of immigrants in New York City.

As of the 2020 Census, Asians became the majority population in Bensonhurst, while the Italian-American population declined to just 9 percent.

In a sign of the times, the bar that once served as the headquarters for Sammy "The Bull" Gravano, the notorious underboss of the Gambino crime family, is now the 👍ike Cafe, a restaurant that offers plates of Hong Kong style fast food like cheong fun and pineapple butter buns.

While there are still plenty of spots to pick up freshly baked cannoli and sfogliatelle, and Cristoforo Colombo Boulevard hosts a parade honoring its namesake every October, Bensonhurst, much like Little Italy in Manhattan, is seeing its days as an Italian-American enclave dwindle.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week's recording features birds, chimes, flapping tarps, and some of the bustle from the markets on 86th Street.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

I was going to feature the work of the great Helen Levitt here because she was born and raised in Bensonhurst, but since she made most of her work in Manhattan, I thought I would save that for another week. Instead, I went back to the well for more Berenice Abbott. These pictures are technically from Bath Beach, but when Abbott took them, it was considered Bensonhurst. Also, since her Changing New York project is such an inspiration don't mind taking liberties with neighborhood borders.

ODDS AND END

I knew I would get in trouble if I didn’t mention that Bensonhurst is home to both a liberty pole and the oldest existing milestone in New York City. So I did.

Besides Helen Levitt, other former Bensonhurst residents include Anthony Fauci, Sandy Koufax, the Three Stooges, and Carl Sagan, who brought us one of the greatest three-and-a-half-minute videos of all time.

Last week, Dutch politician Gerben-Jan Gerbrandy came up with an intriguing counteroffer to current American plans to take over Greenland and Canada. The proposal, to Make New York Dutch Again, could restore New Utrecht to its former glory. Consider me interested.

DeSantis, John. For the Color of His Skin. Pharos Books, NY, 1991.

Imagine seeing all these names like New Utrecht or Breukelen (Brooklyn), but also New York was originally New Amsterdam, and knowing we swapped it (with a slightly heavy conviction from England) for Suriname.

I love your photographs...the shadows, light, colors, textures....your eye is just wonderful! thank you