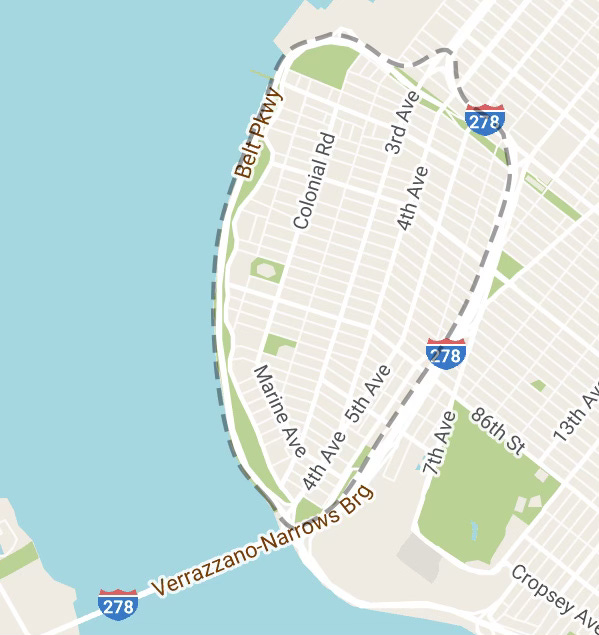

Last week, when I visited Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, I walked nearly eleven miles and barely covered half of the area. It is deceptively large. The neighborhood’s borders are neatly delineated by a trio of Robert Moses projects. The BQE and Belt Parkway encircle the area, crossing paths at the Verazzano Bridge, “gigantic, suspended rainbow arches of steel and stone,”1 reaching across the Narrows and connecting Brooklyn to Staten Island.

Fort Hamilton occupies a large part of the southern portion of the neighborhood, and some people consider the fort and its surrounding blocks a separate entity. 3rd and 5th Avenue are the main shopping corridors, and various styles of attached one and two-family rowhouses line the side streets between them.

While Malba may be the Beverly Hills of New York, Bay Ridge is no slouch when it comes to terracotta palazzos and ersatz chateaus. The southwestern corner of the neighborhood in particular is a world unto itself where the grit and chaos of downtown give way to meticulously manicured expanses of landscaping, half-timbered Tudor facades, and Spanish tile roofs.

On my recent visit, the streets were eerily empty - spotless except for a recent dusting of cherry blossoms.

The only traffic came from a procession of drivers-ed students taking full advantage of the broad and car-free streets to practice their parallel parking.

YELLOW HOOK

Bay Ridge was once part of New Utrecht, one of the original six towns founded in Kings County. The land, bought in 1652 from the Nyack Indians by the Dutch West India Company for the tidy sum of “six shirts, two pairs of shoes, and assorted knickknacks,” was originally named Yellow Hook due to its shape and ochre-colored cliffs.

Dutch efforts to establish New Amsterdam as a global trading nexus had the unintended consequence of bringing diseases previously unknown to the area. For years, settlers had been "popping off like rotten sheep" from the effects of yellow fever, most likely brought over on boats coming from Africa via the Caribbean.

Much like Corona in Queens, the epicenter of the Coronavirus outbreak in New York, Yellow Hook was particularly hard hit by an outbreak of yellow fever in 1849. The unfortunate coincidence was not lost on locals who voted for the new name, Bay Ridge, in 1853. Unfortunately, the change did not immunize the neighborhood from the disease, and Bay Ridge was again at the center of one of the city’s last significant yellow fever outbreaks in 1856.

Candy from Strangers

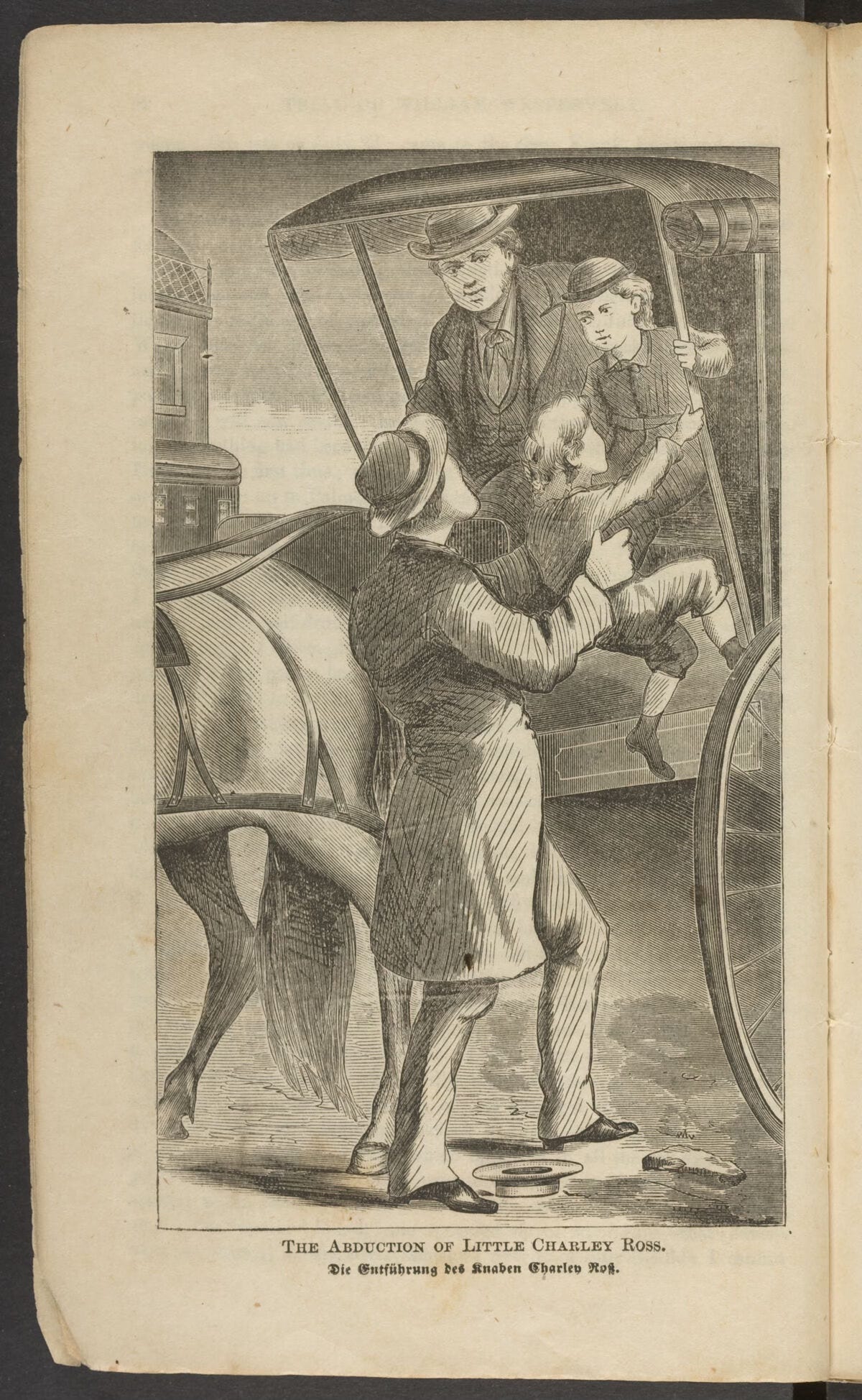

On July 1, 1874, 4-year-old Charley Ross, and his older brother Walter were playing in their front yard in Germantown, PA, when two men pulled up. The men lured the kids into their carriage (the 19th-century predecessor to the white van) with the tempting promise of fireworks and candy. Thus began the first kidnapping for ransom case in America and the origins of the adage, “Don't take candy from strangers.”

The boys were driven about eight miles away where Walter was given a quarter and sent in to buy the treats. When he came out, the carriage was gone. A few days later, Christian Ross, the boys’ father, received the first of twenty-three ransom notes demanding $20,000 for little Charley's safe return.

Mr. Ross- be not uneasy you son charly bruster he al writ we as got him and no powers on earth can deliver out of our hand. You wil hav two pay us befor you git him from us. an pay us a big cent to. if you put the cops hunting for him yu is only defeeting yu own end. we is got him fit so no living power can gits him from us a life. if any aproch is maid to his hidin place that is the signil for his instant anihilation. if yu regard his lif puts no one to search for him you money can fech him out alive an no other existin powers don't deceve yuself and think the detectives can git him from us for that is one imposebel yu here from us in few day.

The kidnappers’ way with words was only superseded by their talent in identifying suitable ransom targets. Christian Ross had recently been bankrupted in the stock market crash of 1873 and could not come up with the money.

Eventually, the city of Philadelphia offered a $20,000 reward for any information pertaining to the case, and Charley sightings began to pour in. Despite the reward and public awareness campaigns that included a tribute song and embossed glass cologne bottles with the boy’s likeness (the precursor to missing kids on milk cartons), nobody had any idea who had kidnapped Charley.

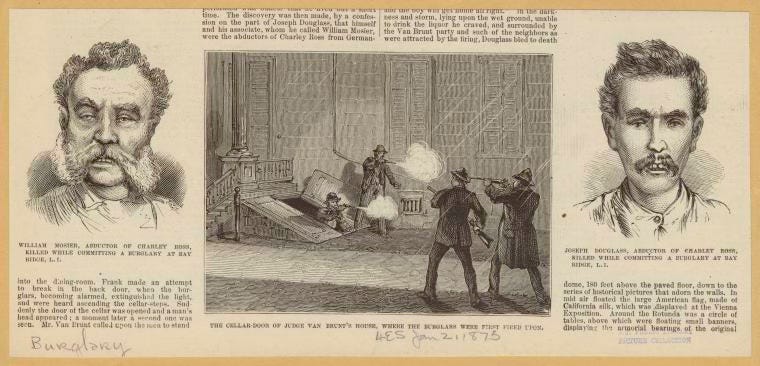

Then, in 1875, a botched robbery attempt at the home of New York Supreme Court Justice and Bay Ridge scion Charles Van Brunt led to a break in the case. Mustachioed scoundrels William Mosher and Joseph Douglass were confronted emerging from Van Brunt’s Bay Ridge home and were both shot. Mosher was killed instantly.

With nothing left to lose, Douglas confessed that it was they who had kidnapped Charley Ross, though he put most of the blame on his accomplice who, having recently perished, was unable to defend himself.

Walter was brought to the morgue to see if the dead men were his brother’s abductors, an identification he easily made due to what he referred to as Mosher’s unmistakable “monkey nose.” It is thought that Mosher most likely had syphilis nose, a condition I HIGHLY recommend you don’t google.

Over the years, nearly 5,000 would-be Charleys surfaced, including Gustave Blair, a 69-year-old carpenter from Phoenix who substantiated his claim by saying he vaguely remembered being held prisoner in a cave as a small boy.

Gustave petitioned a Maricopa County court to recognize him as the real Charley, and the petition, met with far less scrutiny than Maricopa’s 2020 election results, was granted. In 1939, Gustave was legally declared Charley Ross, though the Ross family never believed him. Recent DNA testing has revealed that Gustave, who died in 1943 and whose gravestone reads Charles B. Ross, was indeed lying.

The Fjords of Brooklyn

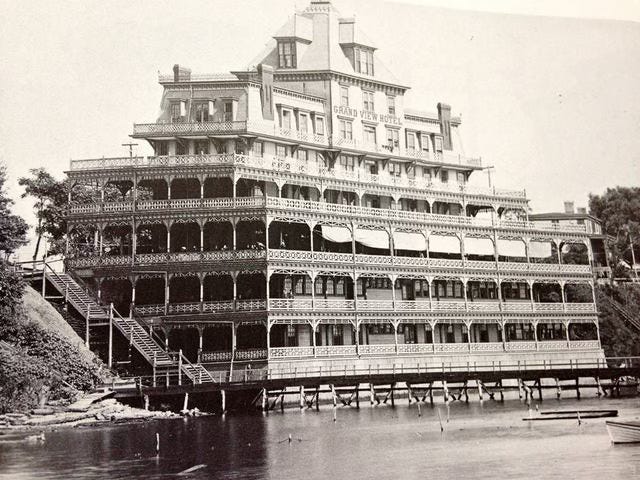

Bay Ridge, despite its reputation as a hotbed of yellow fever and monkey-nosed kidnappers, was a popular spot for the city's wealthy, who built their estates on the high ridge overlooking the Narrows. Closer to Fort Hamilton, beachside resorts catered to working-class Brooklynites who enjoyed frolicking in the sea and patronized the several hotels and saloons that populated the area.

One of those hotels, the Grand View, with room for 1,000 guests and a giant waterslide that led to the Narrows, caught fire in 1893. An explosion in an amateur photographer’s darkroom, set up in the hotel’s basement, was the suspected source. Unfortunately, the conflagration coincided with the annual fireman’s ball, so the local “fire laddies” were unavailable, and the building burned to the ground.2

By the end of the 19th century, the neighborhood was on its way to becoming a suburb. An article from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle lamented the neighborhood’s pending transformation.

The drooping fronds of the willow and the birch show side by side with the sturdier branches of the beech, the elm, and the locust. The wild vine, the Virginia creeper, and the wild convolvulus embrace these trees in a tangled mass of verdure that may too soon pass away to make room for the speculator and the contractor. The clink and clang of the mason's trowel and hammer and the tread of the hod carrier will too soon usurp the whispering winds that make Aeolian music to every ear attuned to other sounds than the chink of dollars. As the march of empire westward takes its way, so, too, the ever-increasing spread of Brooklyn reaches out to embrace this loveliest shore. A few short years and the influences named will have wiped away every trace of the historic past along this romantic shore. The bold bluffs will be leveled into terraces to meet the views of men of narrow minds.

With the construction of the Fourth Avenue subway line, the clink and clang of the mason's trowel and hammer went into overdrive. The neighborhood quickly filled up with block after block of row houses built to accommodate a wave of new immigrants.

By far, the largest immigrant group was from Norway. At one point, over 55,000 Norwegian Americans called Bay Ridge home. In the 1940s, there was probably nowhere outside of Oslo where it would be easier to find a steaming hot plate of lutefisk. For the uninitiated, lutefisk is cod that has been dried in the sun until it “attains the feel of leather and the firmness of corrugated cardboard.”3 The fish is then soaked in lye, the same chemical that is popular among criminals for corpse disposal, until it attains a jello-like consistency. According to Garrison Keillor, “eating a little was like vomiting a little, just as bad as a lot,” which, coincidentally, is how I felt whenever Prairie Home Companion used to come on the radio.

These days, you’re more likely to find a plate of falafel than lutefisk as the neighborhood’s Norweigan population has been replaced by the city’s largest Arab community. Starting with a trickle of Syrian and Lebanese Christians in the early 1900s, Bay Ridge is now home to over 8,000 Palestinians, Yemenis, and Egyptians, earning it the nickname Little Palestine.

VERRAZZANO BRIDGE

When construction finished in 1965, the Verrazzano—Narrows Bridge, spanning 13,700 feet, was the longest suspension bridge in the world. Today, it is still the longest in the US. I could go into more detail, but I’ll leave it to someone who knows everything about the bridge.

Despite organized community protests, Robert Moses, then chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, used the powers of eminent domain to clear the way for the bridge, destroying 800 homes and displacing over 7,000 people in the process.

In an interesting orthographic parallel to the Throg(g)s Neck controversy I wrote about last month, the Verrazzano in Verrazzano Bridge had been erroneously spelled with a single z for over fifty years. In 2018, Governor Cuomo signed a bill mandating the name be officially changed to the correct double z spelling after its namesake, Giovanni da Verrazzano.

Gay Talese, who wrote the definitive book on the Verrazzano’s construction, The Bridge attributed the discrepancy to a "typo and everybody let it go." Maybe those rumors of Moses shaving off a g on the Throgs Neck Bridge to save money aren’t so farfetched after all.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s field recording starts inside one of Bay Ridge’s more famous restaurants, Ayat. That is followed by some impatient kids, a visit to Narrows Botanic Garden, a snippet of a Chinese soap opera and a trip down American Veterans Memorial Pier.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

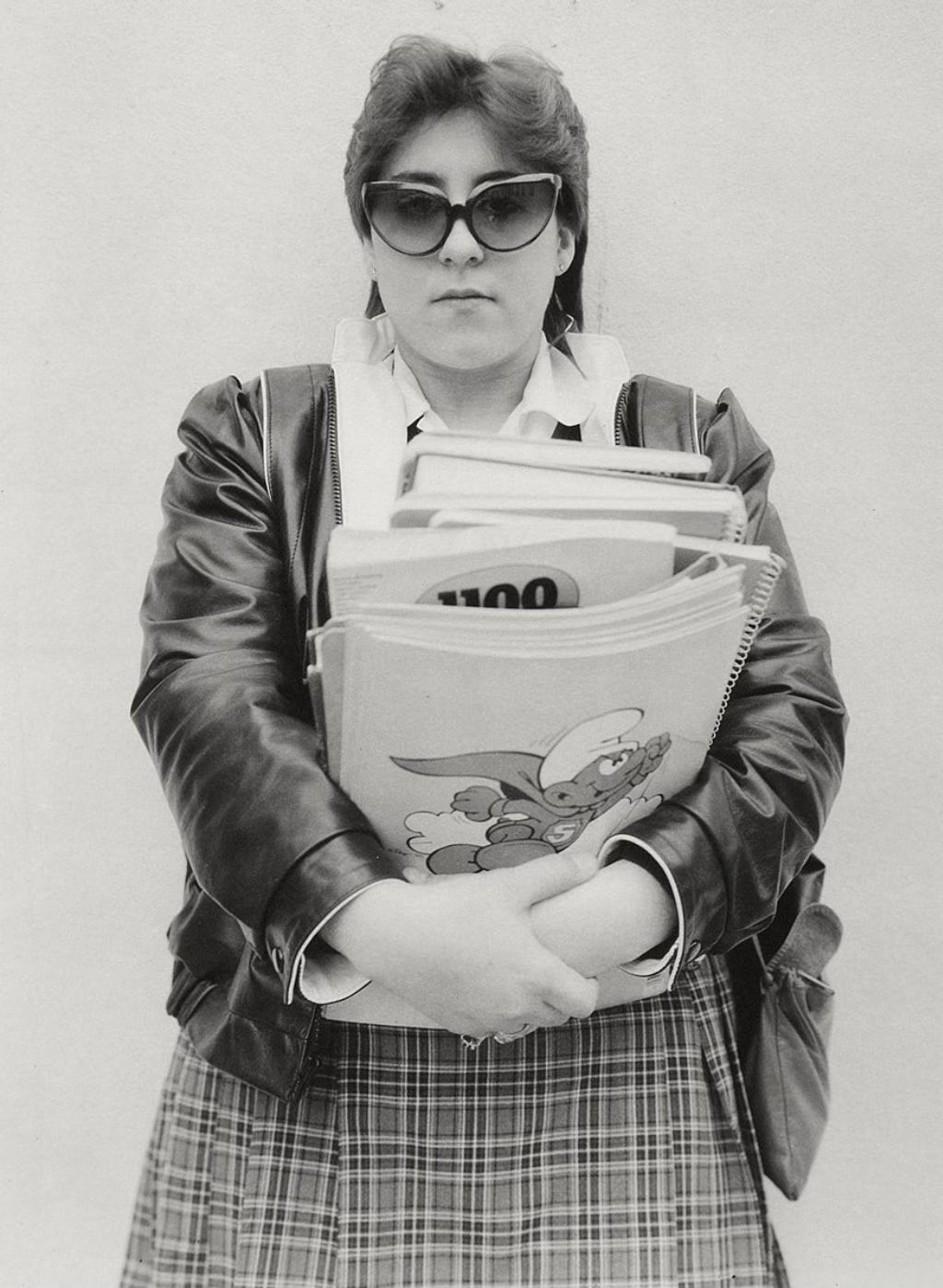

Usually, I’m well into documenting a neighborhood before I begin to look for a photographer to feature in this section. This week, however, I did just the opposite. I was inspired to visit Bay Ridge after coming across Andrea Modica’s beautiful book and project, Catholic Girl. Most of the portraits in the book were shot at her alma mater, Fontbonne Hall Academy in Bay Ridge, in the early 1980s.

Modica works exclusively with an 8x10 camera, and her subjects range from horse operating rooms in Bologna to minor league baseball players and skulls excavated from a mass grave beside a Pueblo Colorado mental hospital. She is also a master platinum printer.

From the intro to the book:

Following Garry Winogrand’s memorial service in March of that year, and a freak New York City snowstorm on that warm spring day, I took the R subway into Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, to visit my high school teacher, the artist Len Bellinger. As usual, I had my 8X10 camera and holders in a backpack, tripod dangling off to the side. Being a diligent student, I took the opportunity to photograph at my alma mater, a largely Italian-American Catholic high school for girls. I was immediately struck with a rush of recognition and terror. I returned to make pictures many times during the following months, knowing intuitively there was something important for me to unpack. Only a few years earlier, within these walls, I had lived my life as a teenager, a time of intense joy and unfathomable grief. Without hesitation, that spring day I jumped off the cliff. I was in love.

ODDS AND END

May 17th, Norwegian Independence Day, is still marked by a parade through Bay Ridge.

Speaking of white vans, in 2015 Australian Ron Jacobs painted “Free Candy” on the side of his van, threw in some bloody looking handprints, and set off for the Burning Man festival. Even though he actually was giving candy to anyone brave enough to ask, Ron got tired of being repeatedly pulled over by the police and decided to sell the van.

If you make it to Bay Ridge, be sure to check out the Narrows Botanical Garden, a small but wonderful volunteer-run botanical garden right alongside the Belt Parkway. - 5/5

I learned so much about Bay Ridge this week from the great Hey Ridge website.

Robert Moses

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1893/01/26/106811668.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Scandinavians’ Strange Holiday Lutefisk Tradition.” Smithsonian Magazine, www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/scandinavians-strange-holiday-lutefisk-tradition-2218218/.

As a Bay Ridge/ south Brooklyn girl, what a pleasant surprise to have stumbled upon your piece!

Poor Charley what a creepy edition

P.S your daughter rules!!!!!!🤘🤘🤘