With a population of around 150,000 people, Astoria is more like a small city than a neighborhood. It's full of sub-neighborhoods, places like Ditmars, Steinway and Astoria Heights. Even ceding Ravenswood and Dutch Kills to Long Island City, the neighborhood is vast and feels like it needs a two-newsletter treatment, so I'll be following up with a second Astoria installment at some point soon.

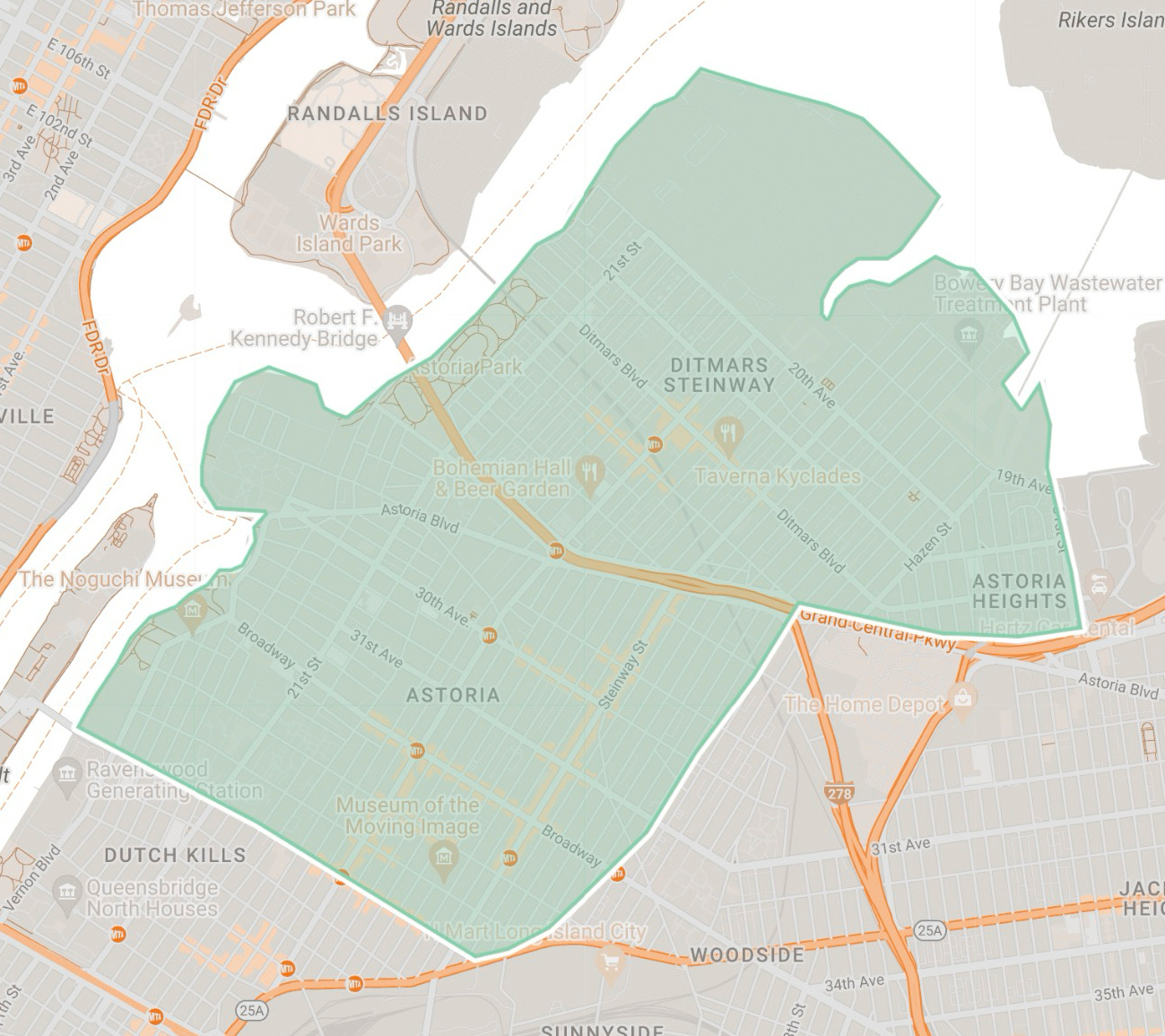

For today’s purposes, I considered the borders of the neighborhood to be the East River to the north and west, 36th Avenue to the south, and 47th Street/LGA to the east. An outline that looks suspiciously like Mr. Magoo in a chef's hat.

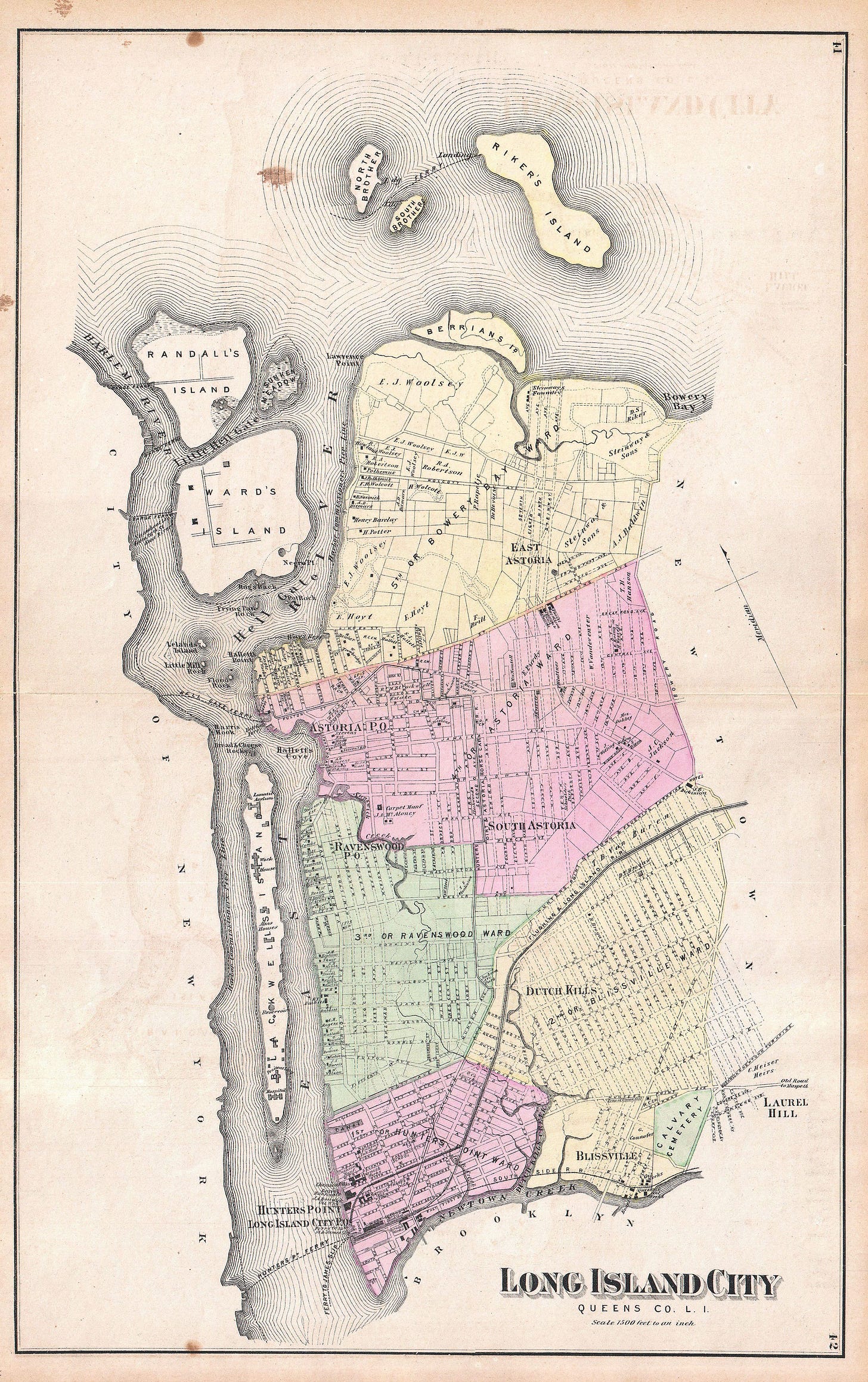

The increasing cachet of a Long Island City address has resulted in the gradual retreat of Astoria's southern border. Long Island City once encompassed the entirety of northwest Queens, so maybe Astoria's shrinking borders are really just a reclamation.

SHOW ME THE WAMPUM

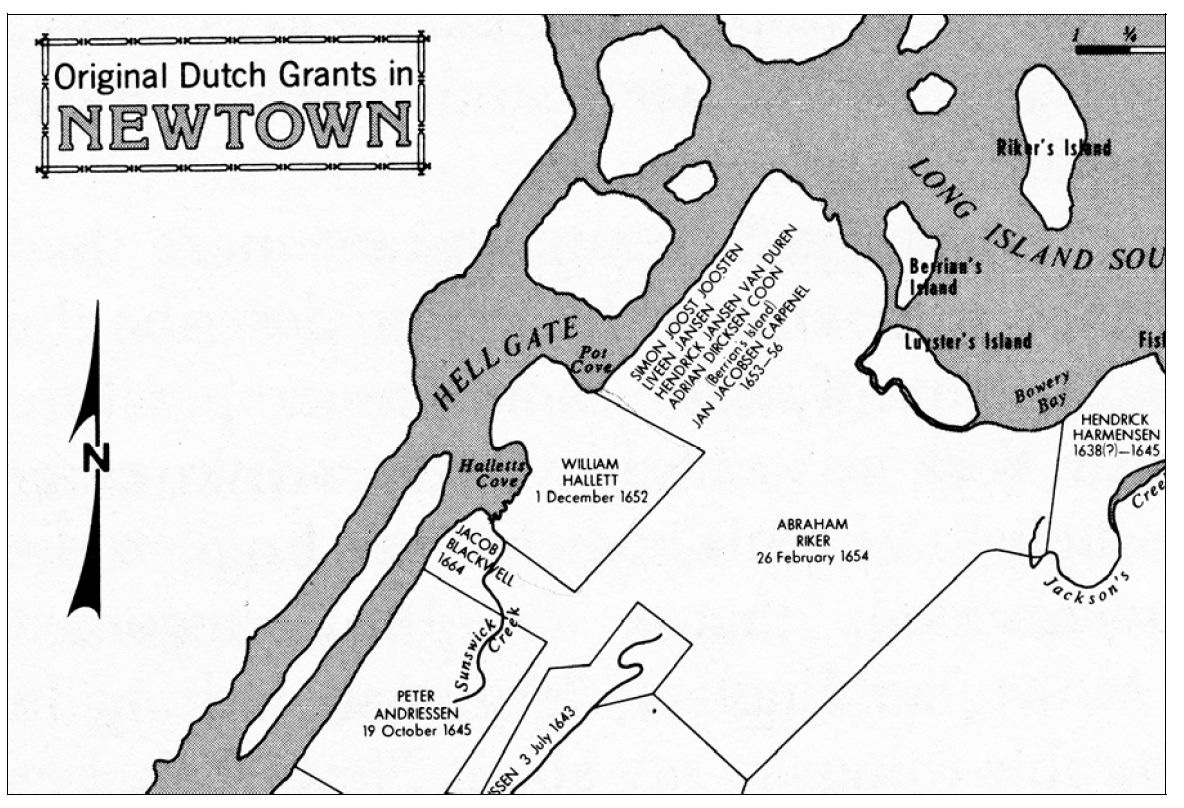

In the 1630s, the Dutch West India Company gave Englishman Jacques Bentyn a grant of 160 acres on the part of Astoria that was once described as “a clumsy excrescence on a smooth shore."1 The Maspeth Indians, who had fished and hunted the shores around present-day Astoria for thousands of years, found the newcomer’s claims of ownership dubious at best. Bentyn was forced to abandon the farm during the Indigenous uprising of 1643.

In 1652, Englishman William Hallett expressed interest in the abandoned property.

William, who must not have paid much attention to recent history, successfully petitioned Governor Stuyvesant for a grant on the old Bentyn farm. Three years later, Hallett's farm was also destroyed in an uprising.

After spending a few years in Flushing, Hallett went behind Stuyvesant's back and repurchased his original farm, adding nearly 2000 acres. Hallett paid two Indian chiefs, Shawestcont and Erramorhar, about $100 worth of wampum, seven coats, one blanket, and four kettles for the land. While this seems like a pittance, it's worth noting that over the years, several different tribes had been "selling" the same tracts of land over and over again to whoever was willing to pony up the most wampum. Shawestcont and Erramorhar actually lived in Staten Island.

The natives referred to the area and the creek that ran through it as Sunswick, meaning "sachem's (or chief's) wife." Hallett named the place Hallett's Cove. He built a brickworks and, later, a mill at the mouth of the creek. Eventually, Sunswick creek became so polluted it had to be covered over.

HELL GATE

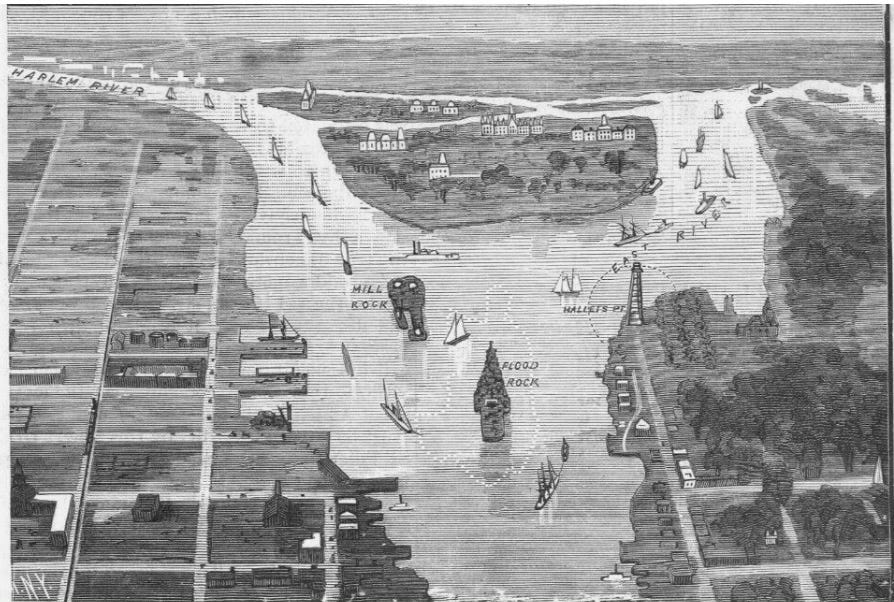

Ferry service connecting the Queens neighborhood to Manhattan’s Yorkville began in 1760. This was not an insignificant journey, as it meant navigating the notoriously treacherous currents and rocky outcroppings of Hell Gate.

The “passage to hell” was responsible for countless shipwrecks, including, most famously, the HMS Hussar. You may remember Joey Treasures’ rather unconventional attempts to salvage the Hussar’s purported cargo of gold bullion in the Port Morris edition.

For about ten miles from New York is a place called Hell-Gate, which being a narrow passage, there runneth a violent stream both upon flood and ebb, and in the middle lieth some Islands of Rocks, which the Current sets so violently upon, that it threatens present shipwreck; and upon the Flood is a large Whirlpool, which continually sends forth a hideous roaring, enough to affright any stranger from passing further, and to wait for some Charon to conduct him through; yet to those that are well acquainted little or no danger.2

By the time the Federal government stepped in to assist in clearing the channel, it was estimated that over 1,000 ships were running aground yearly.

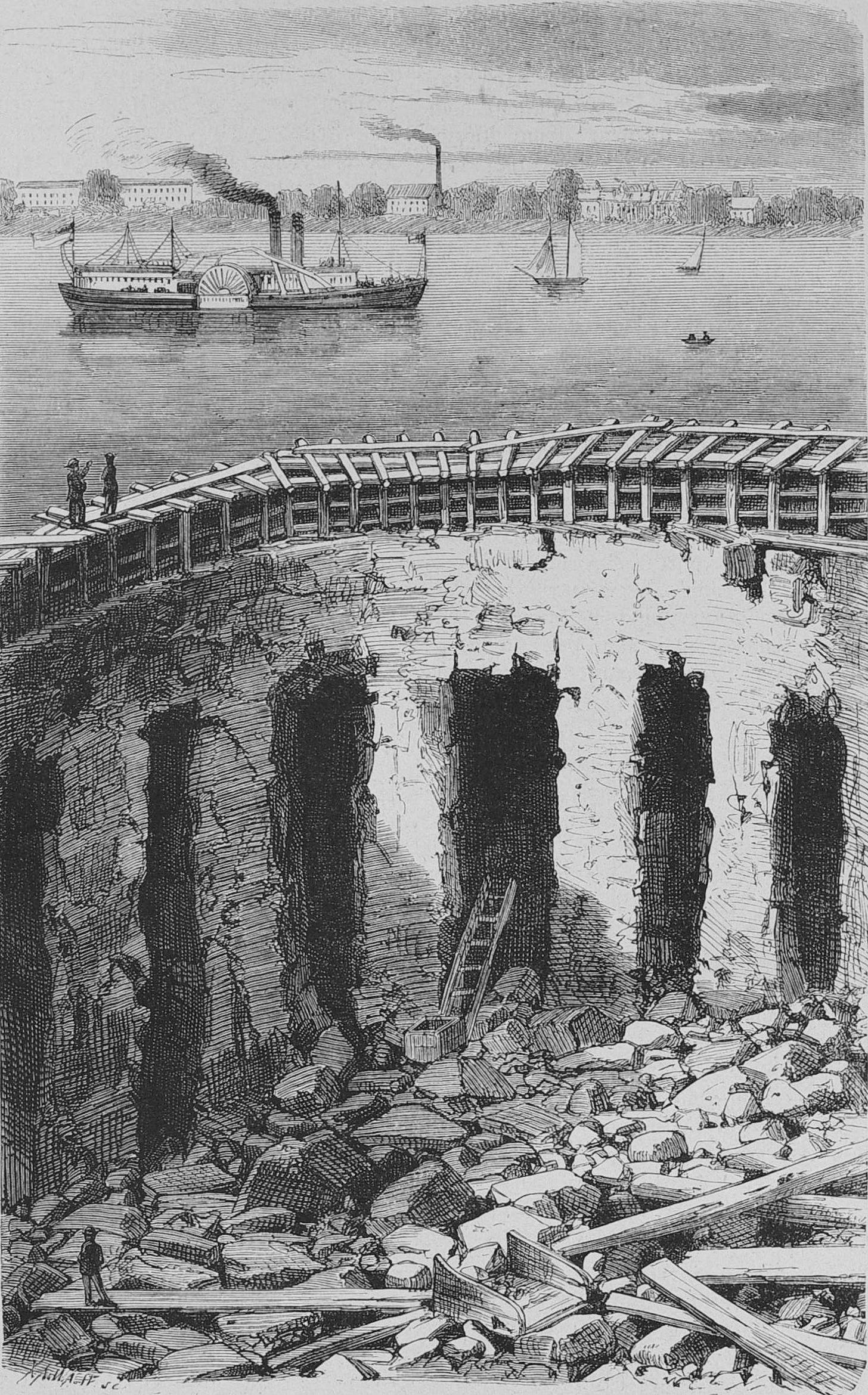

The first obstacle the Army Corps of Engineers addressed was Hallet's Reef. In 1876, realizing that dynamiting from above would accomplish little, the Corps constructed a bulkhead, sucked out the water, and began to dig miles of subaqueous tunnels which they then packed with 50,000 pounds of explosives.

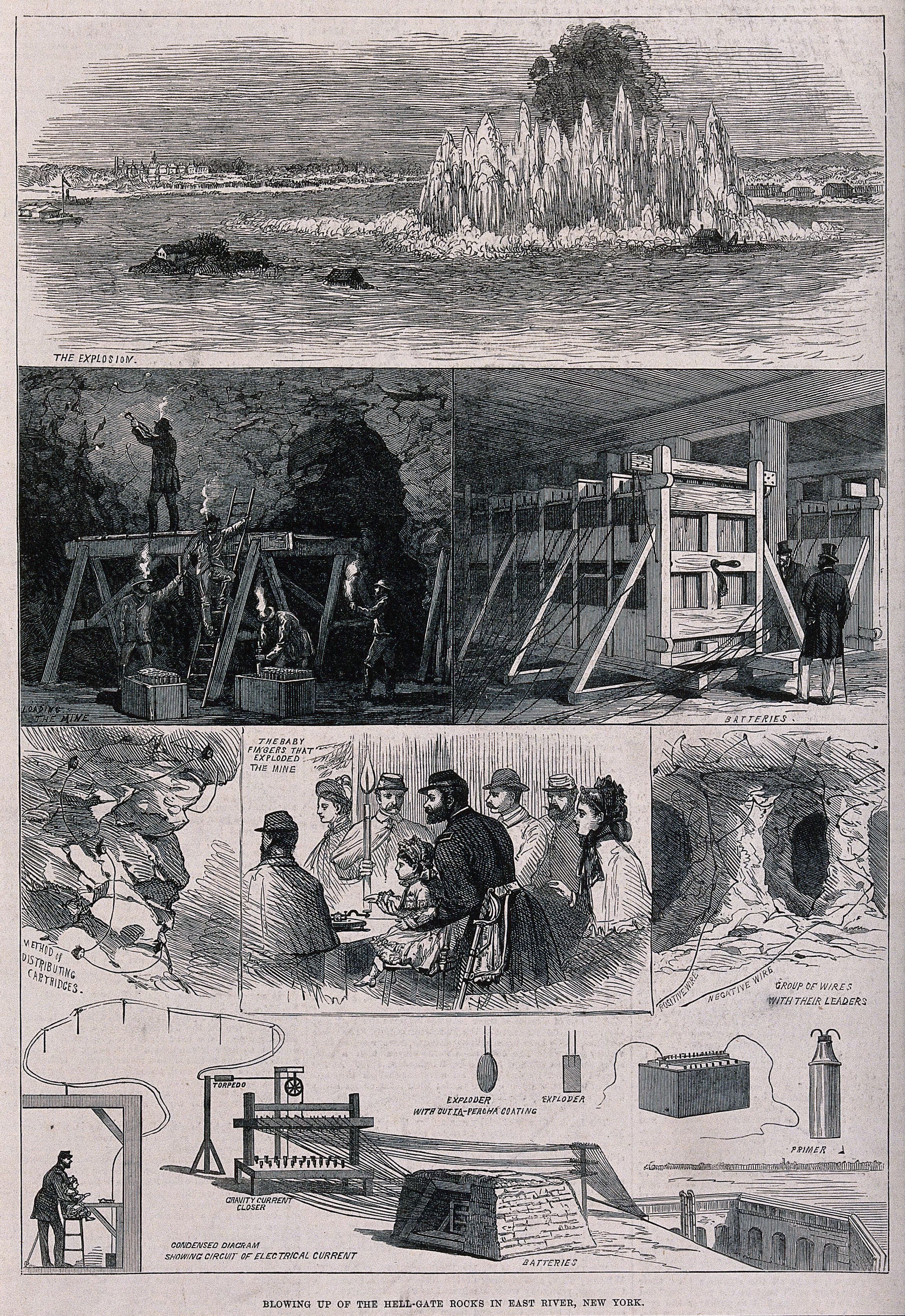

The huge explosion, triggered by 12-year-old Miss Mary Newton, daughter of the chief engineer, instantly reduced the reef to 90,588 tons of broken rock and deepened the channel to 26 feet.

The Corps of Engineers applied their explosive know-how to a cornucopia of other obstacles whose cheerful names belied their capacity for destruction. Shelldrake, Heel Top, Frying Pan, Pot Rock, Bald Headed Billy, and Bread and Cheese Reef were all reduced to rubble thanks to the Corps’ efforts.

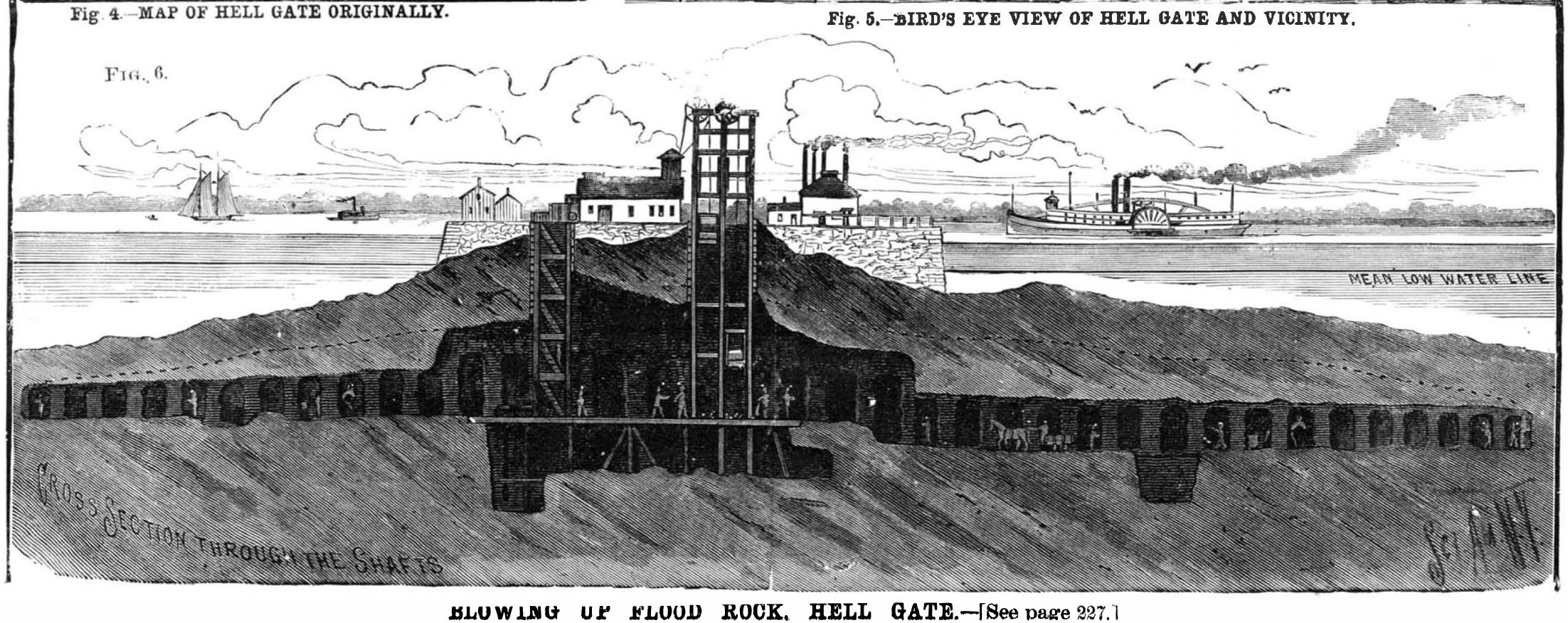

The last and largest obstacle, Flood Rock, was dispatched in October 1885 in one of the most powerful explosions in the world.

I really love these Scientific American Illustrations from 1885. You can see the whole issue here.

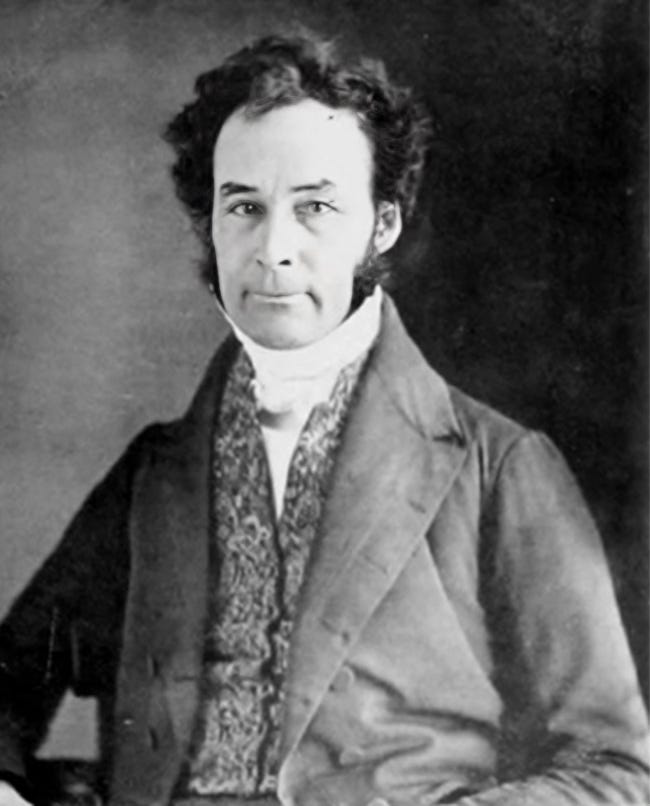

The Father of Astoria

Fur trader Stephen A. Halsey has been called the Father of Astoria, the figure largely responsible for transforming the area from farmland into a bustling village.

The name Astoria comes from Halsey’s efforts to entice fellow fur magnate and America’s first millionaire, John Jacob Astor, to invest in the neighborhood. Astor was not impressed by the gesture.

They named Astoria, Ore., after me and I’m never going out there. And now you’ve named Astoria, L.I., after me and I’m not going out there, either.3

Diss.

It turns out that not all millionaires love having their names plastered over everything in the city. Astor coughed up a measly $500 for the neighborhood that he could see from his summer estate over in Yorkville.

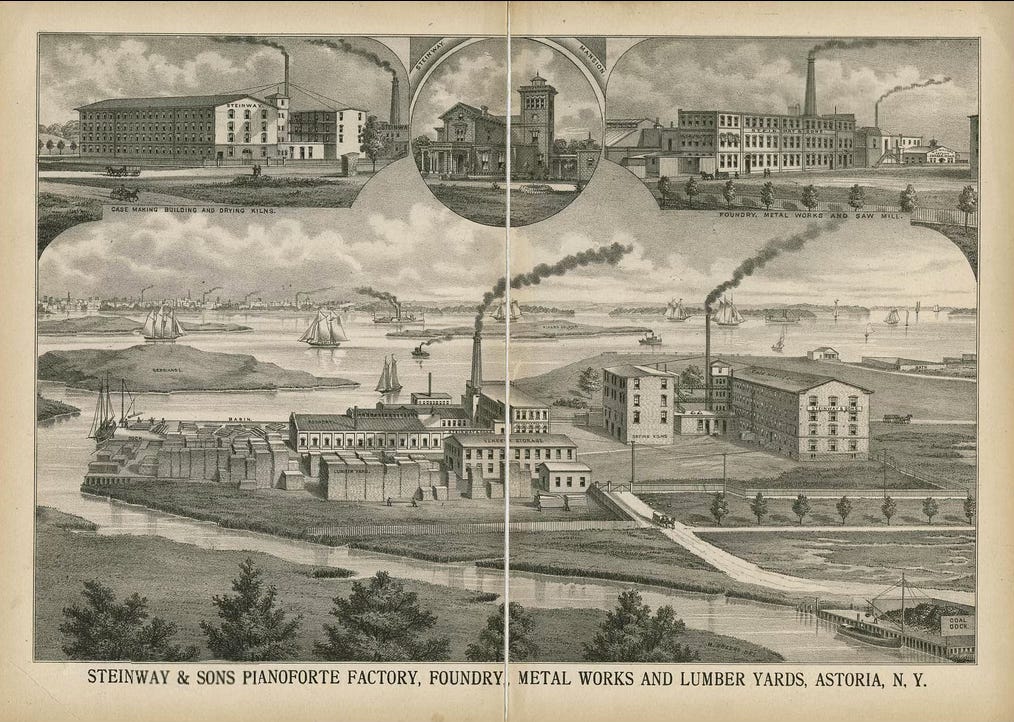

Despite its namesake’s refusal to visit, Astoria continued to grow. Halsey laid out city streets, constructed wharves, and built a large gasworks. During the second half of the 19th century, several large factories opened in the area, including, most famously, Steinway & Sons.

Astoria was incorporated into Long Island City in 1870, and twenty-eight years later, all of modern-day Queens was incorporated into the City of Greater New York.

After World War II, Astoria became the preferred landing spot for Greek immigrants who eventually accounted for nearly half the neighborhood’s population, making it the largest Greek population outside of Athens.

The neighborhood’s Greek community has gradually been leaving the city while other demographic groups take their place. In recent years, Astoria has become one of the city’s most ethnically diverse neighborhoods with immigrants from countries like Egypt, Ecuador, Korea, Columbia, Brazil and Bangledesh all choosing to settle there.

A stretch of Steinway between Astoria Boulevard and 28th Avenue, known as Little Egypt, likely has the city’s highest concentration of hookah bars.

DRAIN BRAMAGE

Last month, I received a somewhat cryptic email inviting me to an experimental music happening.

“Be prepared for light clambering, slippery boulders, and experimental music.”

The event was put on by the Tideland Institute, who “build cultural experiences and social infrastructure that prototypes the future of New York as a vibrant coastal city.”

The night before, I got a vague text with GPS coordinates and a password. The meeting spot was at the edge of what used to be William Hallett’s old farm, today a Costco parking lot.

I followed the directions to a discrete opening in a clump of shrubbery in the back corner of the lot.

Someone was waiting with a checklist behind the bushes and directed me through another hole in a wire fence leading to a small, rocky ravine sloping down to a narrow culvert where three flat rafts were tied up.

A legless grand piano and various other instruments took up the bulk of the middle raft. The other two rafts were already filled with people clustered in groups of two or three, soaking in the late autumnal light.

It was then I noticed the plank—a narrow, bowed board tenuously connecting one of the rafts to the shore. I immediately flashbacked to the first day of a month-long camping trip I took in high school. Within minutes of being dropped off, we had to traverse a branch spanning a small creek. There was absolutely no doubt in my mind that I would fall off this branch. Seconds later, in what some people would describe as a self-fulfilling prophecy, I found myself knee-deep in icy creek water.

While I didn’t have a 50-pound pack this time around, I did have my camera and recording gear, and the memory of my failed creek crossing loomed large. Also, this was a bigger crowd, all armed with high definition video cameras and social media accounts. The stakes were much higher.

Fear is pain arising from the anticipation of evil. -Aristotle

Thankfully, I made it across without incident.

Assuming that weight distribution on such a packed vessel would be of paramount importance, I asked someone who seemed to be in charge where to sit. My question was met with a low chuckle and a vague wave of the hand, so I sat down in one of the last remaining open spots. Someone mentioned we had to wait for the tide to go out and as I watched the sun slowly slip behind the skyscrapers of Manhattan, I had a momentary panic that the plan was to float this rickety assemblage of rafts out into the river.

While the rocks and reefs were long gone, this motley caravan of lifejacket-less musicians and pasty culture vultures would be no match for the unpredictable currents of Hell Gate.

Distraction came in the form of a man sitting across from me who had taken a vial out of his backpack and begun methodically applying a trail of unidentified oil to the warped wooden planks of the raft. I could see some fellow passengers sharing puzzled looks as he painted a liquid border around himself. It seemed like he was either demarcating some ritual space or preparing to dose the whole crew with liquid mescaline, possibly both. When a concerned looking woman next to him leaned in and asked what he was doing, he replied simply, with a slight German accent, “Smell.” Apparently, this was just an innocuous if unconventional application of scented oils.

Seconds later, after a long blast from a baritone saxophone, the ropes were cast off, and we began to move not towards the river but backward, into a large sewer pipe that I later learned was the outflow for the buried Sunswick Creek. If only old William Hallett could see us now.

Since the top of the pipe was only about two feet higher than the top of the raft, sitting upright was not an option. With little time to act before certain decapitation, there was a frenzied redistrubution of bodies as the raft began to enter the tunnel. Since a seated body takes up much less space than a prone one, floor space was at a premium. But there was no time to strategize. I soon found my head precariously resting on what was either someone’s bony ankle or boot heel. By now, the entire flotilla had completely entered the tunnel and was continuing its slow descent into darkness. The roof slipped past, mere inches away from our noses. The smell of sandalwood and lavender was overpowering.

I heard quite a bit of nervous laughter and at least one whispered confession of latent claustrophobic tendencies as we slid deeper and deeper into the dank underbelly of Astoria.

I had been keeping my head ever so slightly elevated to avoid whatever city sludge lurked on the bottom of the boots underneath me, but my quivering neck muscles could take no more, and I had to surrender.

Meanwhile, some of the most strange and wonderous sounds I’ve ever heard were beginning to emerge from the center raft. Deep guttural bleats and long drones from a baritone saxophone, wrapped in a long, languorous, cavernous reverb unlike anything I’d ever heard, bounced off the tunnel’s walls. Gradually, other instruments—accordion, flute, some kind of toy trumpet— joined in, all enveloped in that same endless echo. I stopped trying to imagine what I was lying on and succumbed to the underground sound bath. The ensemble wove together strains of chamber music, polka, and sea shanties punctuated by the occasional distended howl.

At one point, a platter of crackers began to make the rounds. For the life of me, I couldn’t fathom who would want to eat a handful of Cheez-Its while lying flat on their back in a sewage tunnel, but I appreciated the gesture. Later, when the tide had gone out enough that a sort of hunchbacked cross-legged posture was achievable, I was passed what I thought were breadsticks. Since choking seemed less of a threat now that we were semi upright, I decided to be a team player and nosh a stick. Sadly, the breadsticks turned out to be thin, inedible yellow candles. Since I was holding my microphone, I declined the candle. Plus, was I the only person here worried about potential carbon monoxide poisoning? While being slowly asphyxiated by the warm emissions of a hundred candles was surely a more glamorous way to go than choking on stale Cheez-Its, I wasn’t about to willingly take part in my own demise.

As it turns out, nobody died. When we emerged from the confines of the tunnel some 45 minutes later, there was a palpable sense of relief. There was also, for me at least, a sense of loss. I wasn’t sure if I would ever experience sound like that again.

When the plank was cast to shore, this time at a far more precarious angle in the dark of night, I felt like a new person, confident and unburdened by doubt. It was as if those subterranean reverberations had somehow recalibrated things on a molecular level.

This time, I practically ran up the ramp. I also really wanted to take a shower.

Due to a confluence of factors, least of which was my necessary supine position, I neglected to take more than a single picture. Thankfully, Natalie Keyssar took some fantastic photographs for an article in the New York Times about the event last year.

Apparently, last year’s event lacked the danger and intensity of the one I attended. The audience members reclined comfortable on the rocks while the musicians drifted in and out of the tunnel. Also, their plank was double-wide and placed at a very reasonable angle.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s recording is a small representation of my journey into the old Sunswick Creek. Many thanks to N.D and the musicians who are doing their part to keep NYC weird!

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

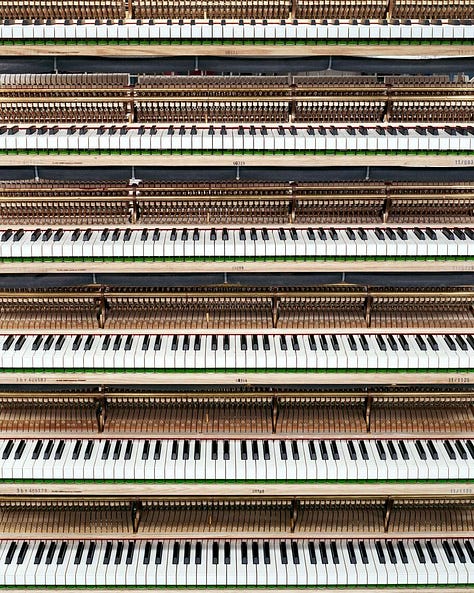

I was introduced to Chris Payne by Jade Doskow, a friend and fellow photographer whose Fresh Kills project I shared here. We had a few Zoom conversations, and I really enjoyed talking with him and hearing about his work. You have probably seen Chris’ photos if you have picked up a NY Times magazine in the past decade. The precision of Chris’ instantly recognizable images reflect his previous career and training as an architect. So much to see on his site.

These photographs are from the series and book Chris did on the Steinway Factory in 2016.

The kind of manufacturing and craftsmanship that happens at One Steinway Place in Astoria, New York, where people transform raw, often messy materials into some of the finest musical instruments in the world, has nearly vanished from the American workplace. This concerns me deeply, not only because I come from a musical family in which such craftsmanship was revered, but because I live in a time when fewer and fewer people make their own music.

ODDS AND END

I’ll go into more detail in the follow-up, but the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum at 32-37 Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City is a must-visit if you are in the vicinity. The museum, founded by Noguchi in 1985, is the oasis of calm that we all need these days. Follow up your visit with a trip to Socrates Sculpture Park, right across the street.

Or, for a more ambitious Astoria outing, you could visit the city’s oldest surviving beer garden, The Bohemian Hall & Beer Garden, followed by a trip to the Jim Henson exhibit at the American Museum of the Moving Image on 35th Avenue at 36th Street. Who doesn’t love beer and muppets? #KermitandKölsch

Here’s a video of the inaugural Drain Brammage event. All the music was performed by Stefan Zeniuk on clarinet and contrabass clarinets.

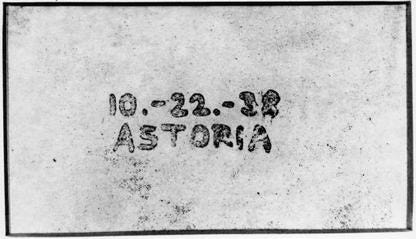

On October 22, 1938, on the 2nd floor of an apartment building at 32-05 37th St, Chester Carlson made the first photocopy in history.

I recently wrote about A Bronx Tale, the movie starring Robert DeNiro that depicts a childhood spent in the Belmont neighborhood in the Bronx. A reader (@danebenko) pointed out that the movie is a sham and was actually filmed in Astoria. Actually, hundreds of movies and TV shows have been filmed in Astoria due in large part to the Kaufmann Astoria studios, which has been producing films since the 1920s.

https://www.loc.gov/item/15019989/

A Brief Description of New-York: Formerly Called New Netherlands (1670) Daniel Denton

https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/beavers-john-jacob-astor

Every week your audience can never tell which way the history of the neighbourhood will go. Fantastic, I will be forlorn when you get to the end and are "complete".

I think you experienced the Willy Wonka boat ride IRL and I’m incredibly jealous.