It’s been a while since I’ve written about the Rockaways, a place I’ve spent many years photographing, drawn to a landscape that, perhaps more than any other in the five boroughs, embodies the tension between city and wilderness. Stretching 11 miles long and averaging less than three-quarters of a mile wide, the peninsula sits between the Atlantic Ocean and Jamaica Bay, feeling about as far removed from the steel-and-glass towers of Manhattan as you can get.

This week, I focused on Arverne, which lies between Beach 59th and Beach 77th Streets. The neighborhood has examples of several of the city typologies that I have collected over the years.

There are split houses

handball walls

and plenty of dead ends

During my most recent visit, I kept encountering scenes I had photographed over a decade ago when still working with my 8x10 camera.

Only when I referenced the original image did I notice the subtle alterations that had occurred over the ensuing years.

These images, taken over a decade apart, suggest a place frozen in time. But Arverne's history tells a different story. From exclusive seaside resort, to urban renewal zone, to its recent revival, this sliver of the Rockaways is in a state of constant flux.

KNOW WHAT I MEAN VERN?

Arverne abuts Edgemere, a neighborhood that I’ve already written about, and both share quite a bit in common. Together, they were the last sections of Rockaway to be developed. Both were envisioned as quasi-European getaways. Frederick J. Lancaster, the man who developed Edgemere, tried (and failed) to get everyone to call the area New Venice, complete with gondolas ferrying residents through the neighborhood.

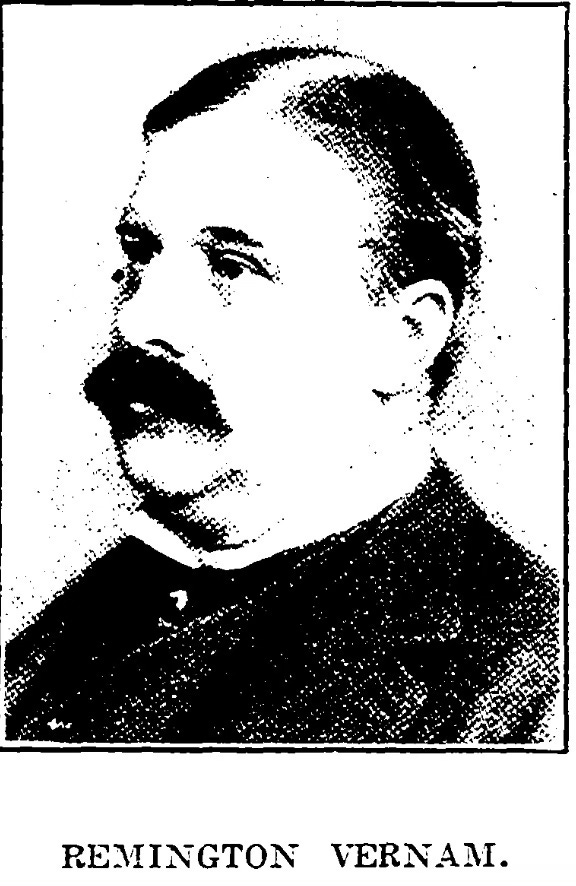

Next door, Remington Vernam and his wife Florence also unsuccessfully lobbied for a canal-centric lifestyle, though they modeled their waterway after Amsterdam’s Amstel Canal. The only remnant of that vision is the undistinguished three-and-a-half-block stretch of Amstel Boulevard, which dead ends into a CALL-A-HEAD porta potty facility.

Vernam, who had spent several summers at Rockaway Beach unwinding from the pressures of his law practice, saw the potential in this undeveloped region of rolling dunes and fisherman’s shacks. Several others were interested in the land, and there was general confusion as to who owned what, with the same lots often sold to several different people. Ultimately, Vernam was able to leverage his legal expertise and emerge from the confusion owning the majority of the new neighborhood. In 1882, Vernam formed the "Ocean Front Improvement Company” and began the process of grading sand dunes, paving streets, and even installing a sewer system.

Credit for the neighborhood’s name goes to Vernam’s wife, Florence, who, as the story goes, was inspired by seeing her husband sign the numerous checks required to develop the area. His signature, “R. Vernam,” hastily scribbled to render the final letters illegible, became R. Verne and, finally, Arverne, which Florence thought “had a nice French sound.” Of course, for those of a certain age, the name might have other associations.

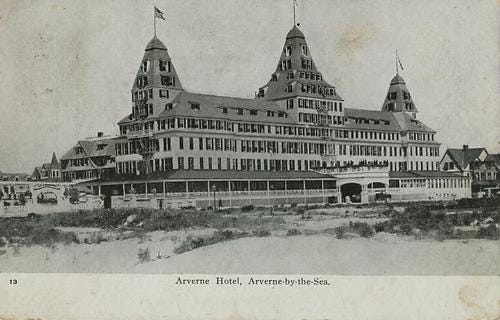

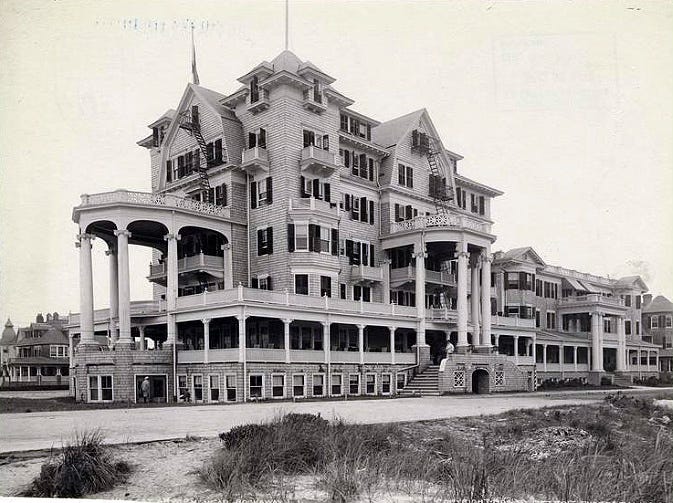

On the 4th of July, 1888, the Arverne Hotel, with room for 400 guests, Italian gardens, and a saltwater swimming pool, opened for business. The next year, Vernam sold 17 “cottages,” large homes for affluent New Yorkers looking to take in the sea air. Several residents led a successful effort to incorporate the village, giving it the name Arverne-by-the-Sea. A boardwalk, bathing houses, and a theater were built, and thousands of visitors came, attracted by “views of the broad Atlantic ocean and enjoyment of the pure ozone wafted in.”

Despite founding what was, by all accounts, a charming and profitable enclave, Vernam soon found himself embroiled in lawsuits over property ownership. By 1898, he was in debt to creditors and had to declare bankruptcy with nothing left but the shirt on his back.

Arverne continued to grow, especially after the electrification of the Rockaway train line, which improved accessibility to the peninsula. More homes and hotels were built. However, as Arverne expanded, it lost some of the exclusive air that had originally attracted New York’s elite.

Then, in 1922, disaster struck—a fire burned through five blocks, destroying over 130 homes and 10 hotels. Low water pressure made containing the blaze particularly challenging, as the stream of water from the firehoses could barely reach past the first floor of any building. Rebuilding efforts got underway almost immediately, but this time, the focus was on summer bungalow rentals and rooming houses rather than grand homes and hotels.

The area remained a popular escape for the middle class, particularly Jewish families, through the 1940s. However, as people had more disposable income and both car ownership and air conditioning became common, places like the Jersey Shore and Long Island soon became the destinations of choice.

URBAN RENEWAL

In my Edgemere post, I covered Robert Moses’ Rockaway Development Plan, which aimed to relocate New York’s poorest residents to the city’s outermost reaches. Robert Caro’s The Power Broker recounts a visit to Arverne by an employee of the city’s Housing and Urban Development department on a bitter winter day in the 1950s. The lawyer was shocked to see that the “sprawling colonies of summer bungalows, flimsy little structures, each barely big enough to accommodate a single family,” were packed with residents displaced by previous urban renewal projects.

The overcrowding was no accident. These families had been strategically relocated to Arverne, creating conditions that would justify its classification as a "blighted" area and make it eligible for demolition under Title I of the Housing Act. Since the area was no longer attracting much of the summer crowd, landlords were happy to get new tenants, while the government-subsidized rents gave them little incentive to maintain their properties.

Many of these families had already moved from other condemned neighborhoods several times. Some families had moved three or four moves within Arverne, from one building scheduled for demolition to another.1

“These moves placed Arverne’s tenants on the far side of the nightmares—hotels, in a kind of never-never-land of pain, the city’s wandering, abandoned tribe.”

This cycle of demolition and displacement continued until 1973, when the Nixon administration announced a moratorium on federal housing subsidies. By then, over 300 acres had been cleared, and the land would remain vacant for decades.

ARVERNE BY THE SEA

Several proposals were floated to develop the 306 vacant acres between Beach 34th Street and Beach 81st Street, designated as the Arverne Urban Renewal Area. Perhaps the most ambitious was Destination Technodome, a “futuristic pleasure palace” that would have featured an indoor ski slope, two ice rinks, a driving range, Olympic-size swimming pools, and basketball and tennis courts. However, the project’s $1 billion price tag made it a tough sell.

Instead, in 2002, construction began on Arverne-by-the-Sea, a 2,300-unit development on the area’s western half.

The complex of nautically inspired homes—with white picket fences, rooftop terraces, and private streets named Seaspray Avenue and Coral Reef Way—feels more like a Norwalk condo development than a neighborhood in Queens. New York Magazine described its aesthetic as “Saltwater-Taffy Revival, or Clever-Developer Chic.”2 Built to withstand extreme weather, the steel-framed homes feature hurricane-grade windows and sit on concrete slab foundations and wooden pilings that elevate the floors three additional feet above ground. Before construction, the entire site was raised nearly five feet and equipped with stormwater drains, underground electrical lines, and waterproof transformers.

These precautions, along with the natural buffer of one of the peninsula’s widest beaches, proved critical when Hurricane Sandy slammed into the Rockaways in 2012. While much of the peninsula suffered devastating damage, the buildings of Arverne-by-the-Sea emerged virtually unscathed.

.

HEROES

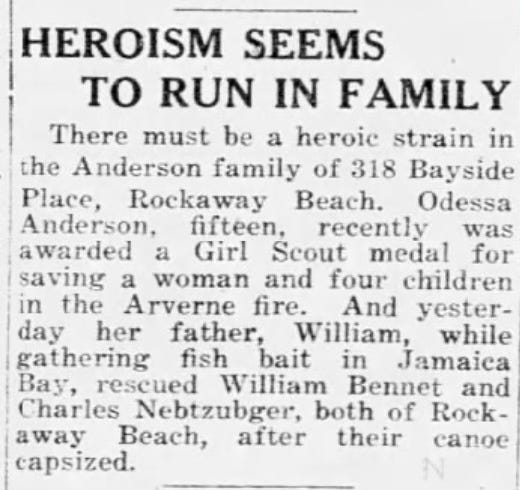

While researching the 1922 fire, I came across the story of 15-year-old Girl Scout Odessa Anderson.

Wearing only her bathing suit, Odessa repeatedly slipped through police barricades to rescue people trapped by the fire, including a baby and her mother, as well as a family of five stranded on a burning houseboat. She suffered several burns and a sprained ankle in the process. When asked why she risked her life, she simply replied, “She was a Girl Scout, and the motto of the organization is to ‘help other people at all times.’”

Odessa wasn’t the only heroic Anderson as just a year later her father rescued two men whose canoes had capsized in Jamaica Bay.

I also found a third article mentioning an Odessa Anderson who rescued a drowning boy in Oceanside, California, four years after her first daring rescue. Of course, this could have been a different Odessa Anderson (the 286th most popular baby name in 1907), but given that this family already sounds like the Roaring Twenties’ version of The Incredibles, I’d bet it was the same one.

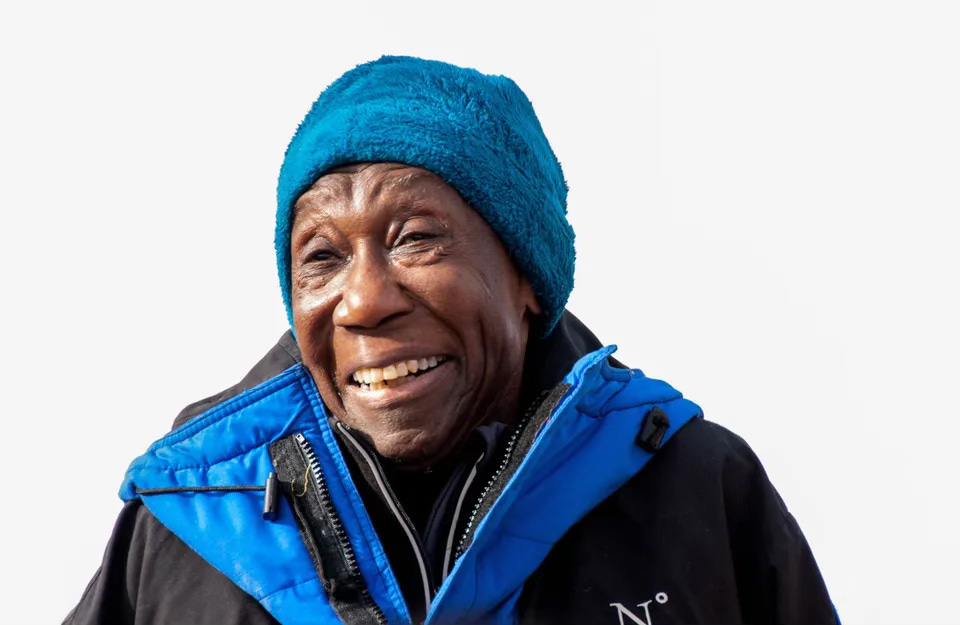

A more recent hero from Arverne is Barbara Hillary. After retiring, she set her sights on the North Pole. Raising enough money to join an expedition, she achieved her goal in 2007 at the age of 75, becoming the first African American woman to reach the North Pole. A few years later, at 79, she traveled to the South Pole.

“Wouldn’t it be better to die doing something interesting than to drop dead in an office, and the last thing you see is someone you don’t like?”

Ms. Hillary, who spent 55 years as a nurse, was born in San Juan Hill in 1931 (another neighborhood cleared under Title I) and grew up in Harlem before moving to Arverne. In addition to her love of extreme travel, she founded the Arverne Action Association and was known for her appreciation of" “archery, firearms, knives, big trucks, and big dogs.”

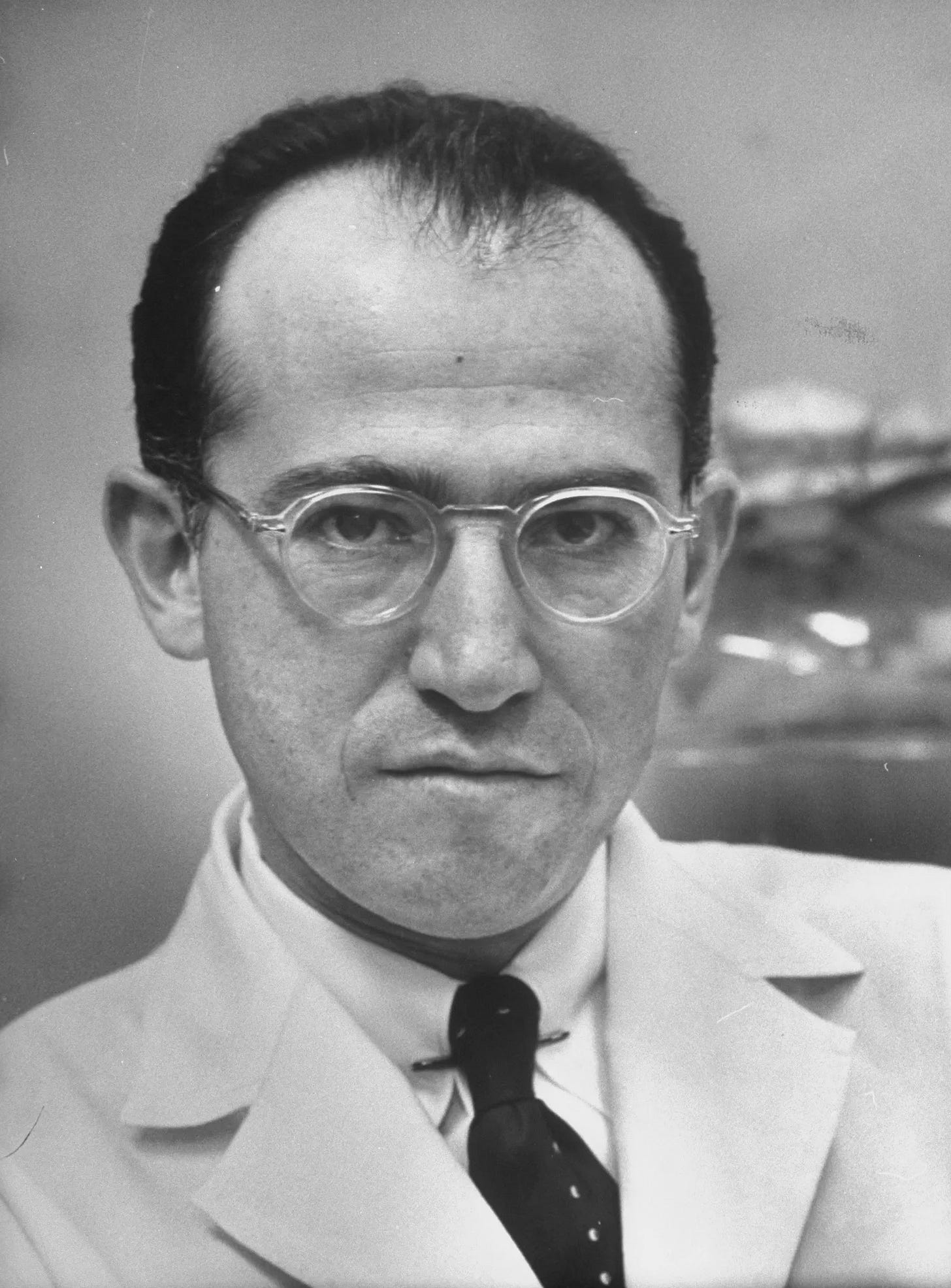

Last but not least is Jonas Salk, who spent part of his childhood at 439 Beach 69 Street in Averne. While he may not be a hero to our incoming health secretary, Salk developed the first successful polio vaccine. Putting him at further odds with the current administration (and cementing his hero bonafides), Salk declined to patent or seek to profit from the vaccine.

HOLY LAND

I first drove by this house in 2011. The sign on the front gate proclaimed: JUDGEMENT DAY MAY 21ST, 2011 GOD IS COMING

I can only assume May 21st was the day the cross went up because this is what I saw when I came back two years later.

Everytime I visit, something has changed.

The man behind the display is Hector Figueroa, aka The Ultimate Inventor.

His goal is noble: to end poverty. His methods are unconventional. His plan appears to be raising money through the sale of his many inventions.

There is the Quick Cool Party Animal, a “gravity pressured ice” cooler with room for 40 glasses. Or the Store & Oar, a rooftop cargo box that doubles as a row boat. The Uni-Tow is advertised as luggage that can push your car. Topping the list is the Electro Babywalk USA™, a remote controlled baby stroller with DVD player. Just in case you think a remote controlled stroller sounds dangerous, not to worry, this one comes with a roll bar.

If these stills from Hector’s video advertising his inventions don’t entice you to click on the link, you may be in the wrong place.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week's field recording features snow melt dripping onto a metal roof, gulls and airplanes over Jamaica Bay, an exuberant dog, and the sounds of the Atlantic Ocean.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

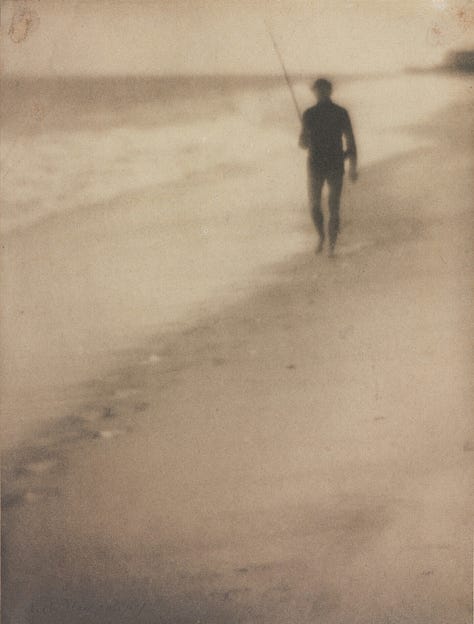

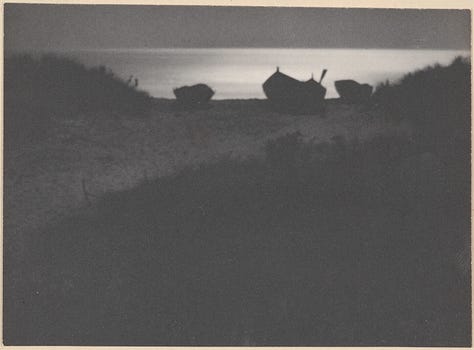

Karl Struss (1886–1981) began his career as a photographer before transitioning to Hollywood, where he won the first Academy Award for cinematography. He studied under Clarence H. White and was a member of Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession group, which championed Pictorialism—a movement that prioritized artistic expression over documentary accuracy. Pictorialist photographers used techniques such as platinum and gum bichromate printing, along with soft-focus lenses, to create images that resembled paintings more than traditional photographs.

In the summer time Struss’ family rented a cottage in Arverne and he made several pictures during his time there.

Like Hector Figueroa, Struss was an avid inventor. He developed the Struss Pictorial Lens, an early soft-focus lens favored by photographers and filmmakers, as well as a rolling tripod stand. He also pioneered a technique using red makeup and red and green filters to create eerie on camera transformations, most famously demonstrated in the 1937 film Sh! The Octopus.

Today, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art houses over 2,000 of Struss’ prints.

ODDS AND END

Not surprisingly, the Arverne by the Sea development has led to the creation of several new businesses in the area. In addition to a much-needed grocery store, there is a restaurant row of sorts, including Locals Collective, a coffee shop run by the Locals Surf School, Claudettes—a Moroccan-Israeli-inspired restaurant whose previous location I visited a while ago and thought was great—and Super Burrito, offering Mission-style burritos to the post-surf crowd. I can vouch for the Vegan Poblano and the decor.

If you are looking for a Karl Struss film to watch this weekend, maybe consider Charlie Chaplin’s masterpiece the Great Dictator?

Barrett, Wayne. “No New Shantytown,Just the Same Rubble.” Village Voice, 19 Aug. 1971, pp. 23–25.

Nobel, Philip. “The Best Places to Live in NYC - Why Arverne by the Sea Is the City’s Most Improbable New Neighborhood -- New York Magazine - Nymag.” New York Magazine, nymag, 8 Apr. 2010, nymag.com/realestate/neighborhoods/2010/65358/

Thanks.

It was quite magical.

In general, Rockaway was great back then.

There was an amusement park around 95th street called Rockaway's Playland and

concessions with food and rides and games on 35st.

There was a city run boardwalk restaurant in Arverne that had excellent clam chowder.

I used to ride my bike a lot on the boardwalk.

I didn't eat the porgies or the flounders that I caught in Arverne.

I released them and if they died, I fed them to Seagulls.

Thanks for the memories.

As a child, I summered in Rockaway, both in Belle Harbor and in Arverne, where we owned property.

My sister owned an apartment in the Surfside Towers--which looked much like the photo of the terraced apartment building you show (Dayton Towers).

It was not in Arverne but on 104th street near the boardwalk.

Later, we sold our property and bought a place in the Hamptons.

I loved Rockaway.

I used to fish for striped bass in Arverne and I had summer friends on 57st in Arverne.

There was also a decaying dock in Arverne on the bay side where I fished for Porgies.

Most Arverne teens went to Far Rockaway High School.

Salk did not go there, but Richard Feynman did.

It was a non-magnet school that graduated three science Nobel laureates.