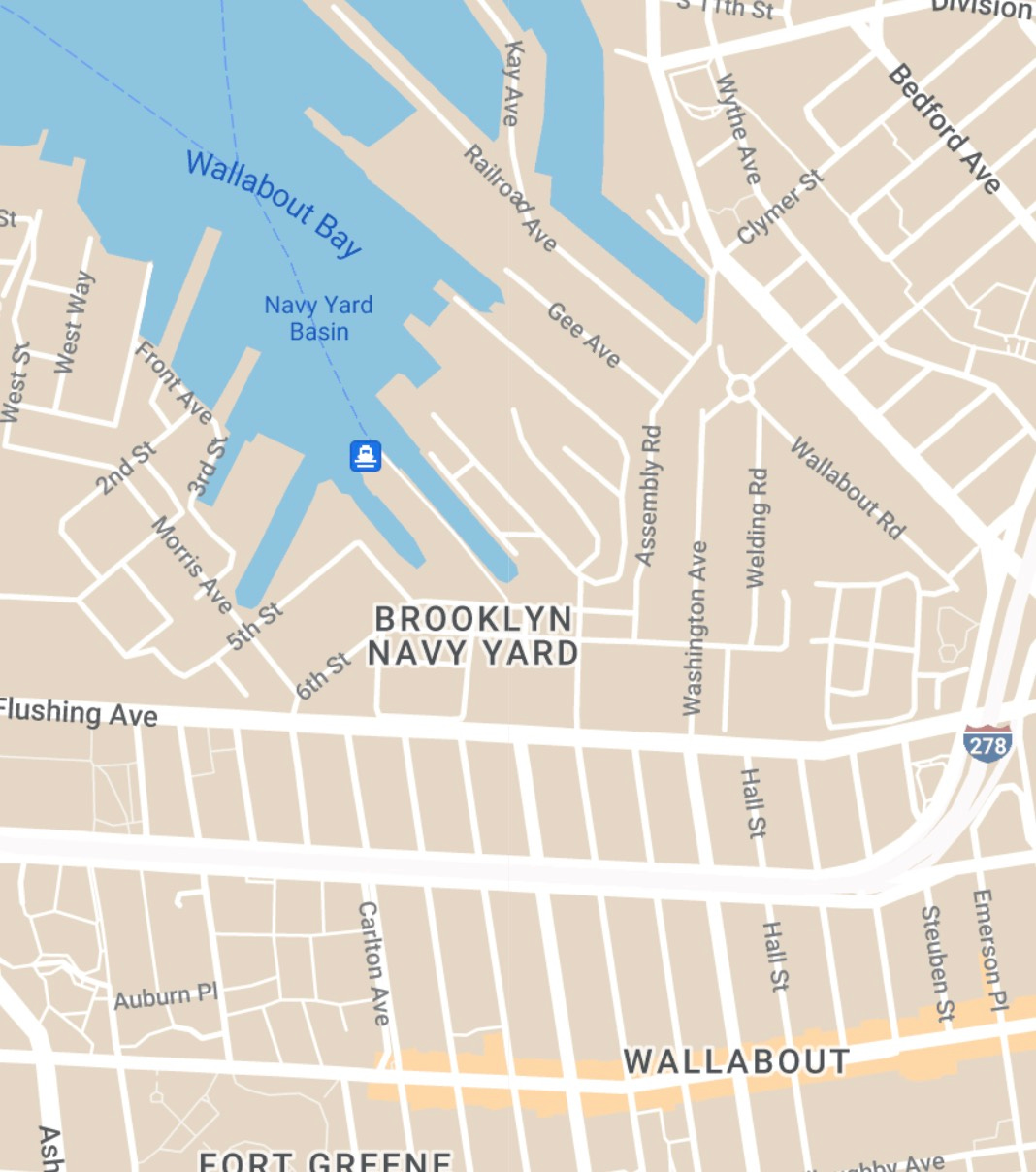

I'm happy to be back with the second installment of my 2 part look into the neighborhood of Wallabout in Brooklyn. It may seem overkill to dedicate two newsletters to one neighborhood, especially when, according to the NY Times, less than 10% of its residents think it exists. But here we are.

Last week focussed on the Navy Yard and the bay that gives Wallabout its name.

This week, I am looking at the remaining vestiges of one of Brooklyn’s oldest neighborhoods, situated between Flushing and Myrtle Avenue and home to the city's largest concentration of pre-Civil War wood-frame houses.

The construction of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway in the 1960s cleaved the neighborhood in half; the elevated highway and its constant thrum of traffic separated the largely industrial buildings on one side of Park Avenue from the residential buildings on the other.

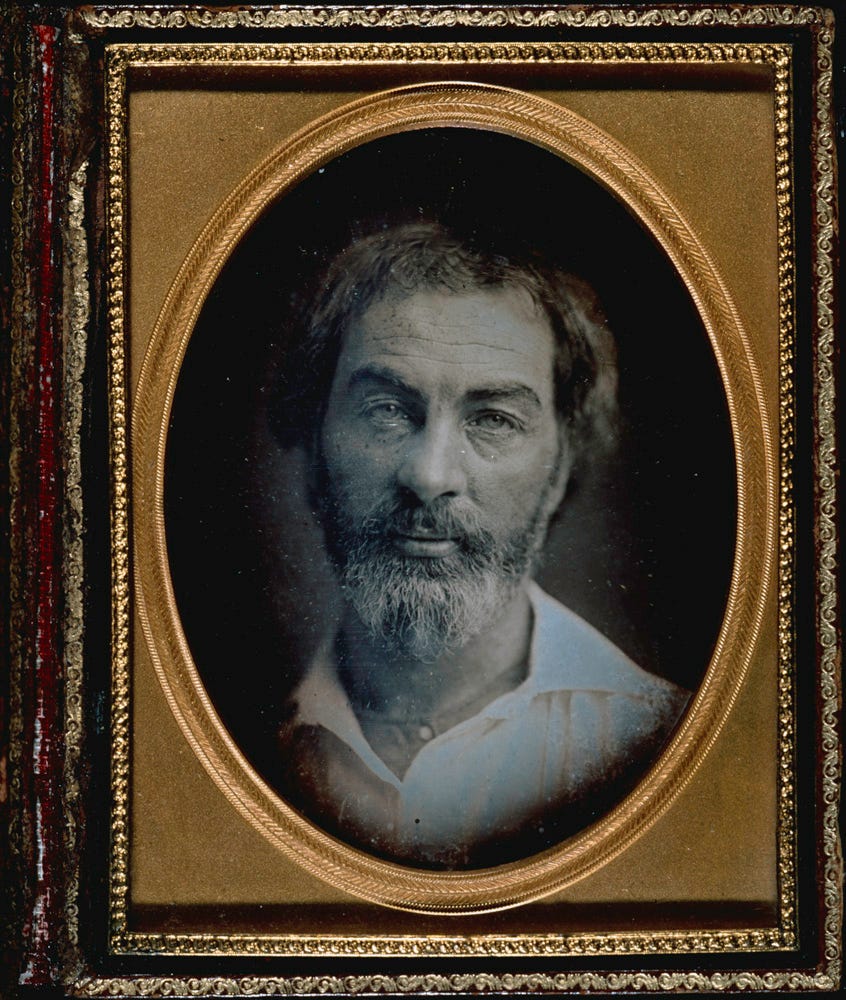

WALT

What sobers the Brooklyn boy as he looks down the shores of the Wallabout and remembers the prison ships, What burnt the gums of the redcoat at Saratoga when he surrendered his brigades, These become mine and me every one, and they are but little, I become as much more as I like. Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

Perhaps the most famous of those residential buildings is 99 Ryerson, a home once occupied by Walt Whitman while he was putting the finishing touches on Leaves of Grass.

It’s not much to look at today. The unprepossessing aluminum-sided house stands out from its neighbors, not because of its rich cultural history but because of the one-story extension that makes it taller than the adjacent buildings.

That extension is part of the reason the home has never received landmark status. The Landmarks Preservation Commission’s heavy emphasis on architectural purity, and the fact that Whitman lived here for less than a year (1855-1856), were cited as the principal reasons why it was not landmarked. This despite pleas from heavy hitters like Martin Scorcese, former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky, and author George Saunders, who wrote:

To protect a house like this one, it seems to me, is a form of cultural stewardship. For this house to disappear would be like an extinction: such a place cannot be returned, not ever, once it is lost.

Though the peripatetic Whitman had over thirty different residences in New York City, the modest building on Ryerson St is the only one still standing. Landmark talks are ongoing.

I AIN’T AFRAID OF NO GHOSTS

Perhaps the second most famous house in Wallabout is the Lefferts-Laidlaw House at 136 Clinton Avenue. The villa, which holds the distinction of being the only remaining Greek Revival temple-front home in Brooklyn, was built around 1840 by Rem Lefferts and his brother-in-law John Laidlaw. It was 38 years later, however, when the house was occupied by Mr. Edward F. Smith, his family, and two boarders, that things began to get strange.

One night, Mr. Smith heard the doorbell ring, but when he went to answer it, nobody was there. Much to Mr. Smith’s increasing annoyance, this happened several more times and was later accompanied by a rattling and pounding of the back doors.

Mr. Smith attributed the disturbance to the wind, and everyone went to bed. The following night, however, the same strange “rappings and ringings” occurred, and the residents began to consider the distinct possibility that their house was haunted. The family posted sentries at the doors, and an enterprising Mr. Smith even sprinkled ashes and flour on the porch to reveal any footprints. Again, the bell rang, and the windows rattled, but no footprints or reprobrates were found.

At this point, there was nothing left to do but call in the police, who were able to confirm the noises but were unable to determine their cause. They returned the following evening with several officers staking out the windows and doors in hopes of apprehending the degenerate door rattler. Not only were they unsuccessful in finding the source, but they were further humiliated when a brick came crashing through the dining room window. According to the Times, this was “the most serious demonstration the invisible agency had yet made, and can only be accounted for on the theory that the ghost, if ghost it was, wished to show its contempt for the Brooklyn Police.”1

After unsuccessfully searching the house for any concealed wires or other trickery that could explain the unexplainable, the police, it seems, gave up. So, apparently, did the ghost. After three weeks of haunting, the brick throwing and door rattling stopped. Unfortunately for Mr. Smith, the doorbell ringing did not stop, but this time, the ringing had a corporeal origin, namely the throngs of eager Spiritualists who had descended upon the house in droves.

According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, spiritualism is “a movement based on the belief that departed souls can interact with the living.” At the time, there were over 8 million Spiritualism adherents in the US and Europe, and Wallabout was lousy with them. The paranormal hijinks in the Smith home were the talk of the town.

Mr. Smith didn’t have much time for these theories. It’s likely Smith was skeptical of the whole Spiritualism movement as accusations of fraud perpetrated by mediums and other organized spiritualists were widespread.

Take the case of Mina Crandon, who, mid-seance, would procure “a tiny ectoplasmic hand from her navel, which waved about in the darkness.” Ectoplasm, defined as a “supernatural viscous substance that exudes from the body of a medium during a spiritual trance,”2 was big in the late 19th century. In this case, it turned out that the hand was a carved chunk of animal liver, a revelation that quickly ended Mina’s career.

Another famous medium, Helen Duncan, was a prodigious producer of ectoplasm. The source of her spiritual goo was later discovered to be lengths of cheesecloth and bits of paper stuck together with egg whites that she swallowed and later regurgitated. She even claimed to have a spirit guide named Peggy, who would sometimes emerge from her nose.

No ectoplasmic events were observed on Clinton Avenue, though impromptu seances did occur for several weeks after the supposed hauntings had subsided.

GUTTERS RUN FUDGE

The Rockwood Chocolate Company was once one of the largest chocolate manufacturers in the country, second only to confectionary juggernaut Hershey’s. In 1904, they relocated from Cherry Street in Manhattan to Wallabout, where the company occupied 16 buildings.

Their headquarters, on the corner of Washington and Park, formerly belonged to the Von Glahn Brothers, a wholesale grocery supply business whose name still graces the front of the building.

On the morning of May 12th, 1919, a fire broke out in the Rockwood shipping department. Piles of burlap sacks, overflowing with cocoa beans and chocolate bars, put up little resistance against the rapidly intensifying conflagration and quickly melted into a molten chocolate river that burst through the doors and continued flowing down Waverly Avenue toward the bay. In no time, the storm drains were clogged with congealed clumps of cocoa butter, and the streets became a roiling mass of liquid fudge.

Word of the chocolate river spread as quickly as the flames, and within minutes, “a thousand and one urchins hurried to the fire” to witness the miracle. In an Augustus Gloopian frenzy, the children began using their hands to scoop up as much of the chocolate as they could. Eventually, several buses arrived to escort the “chocolate-gorged truants, some with faraway looks in their eyes”3 back to school. Negotiating the greasy butter-slick sidewalks proved particularly treacherous, and it took the firefighters several hours to put out the fire.

Today, the Rockwood building has been converted into condos apartments and rebranded as the Chocolate Factory Lofts. Among the many amenities the building lists on its website is the ground floor Laffaholics comedy club. Unfortunately, no mention is made of a chocolate river.

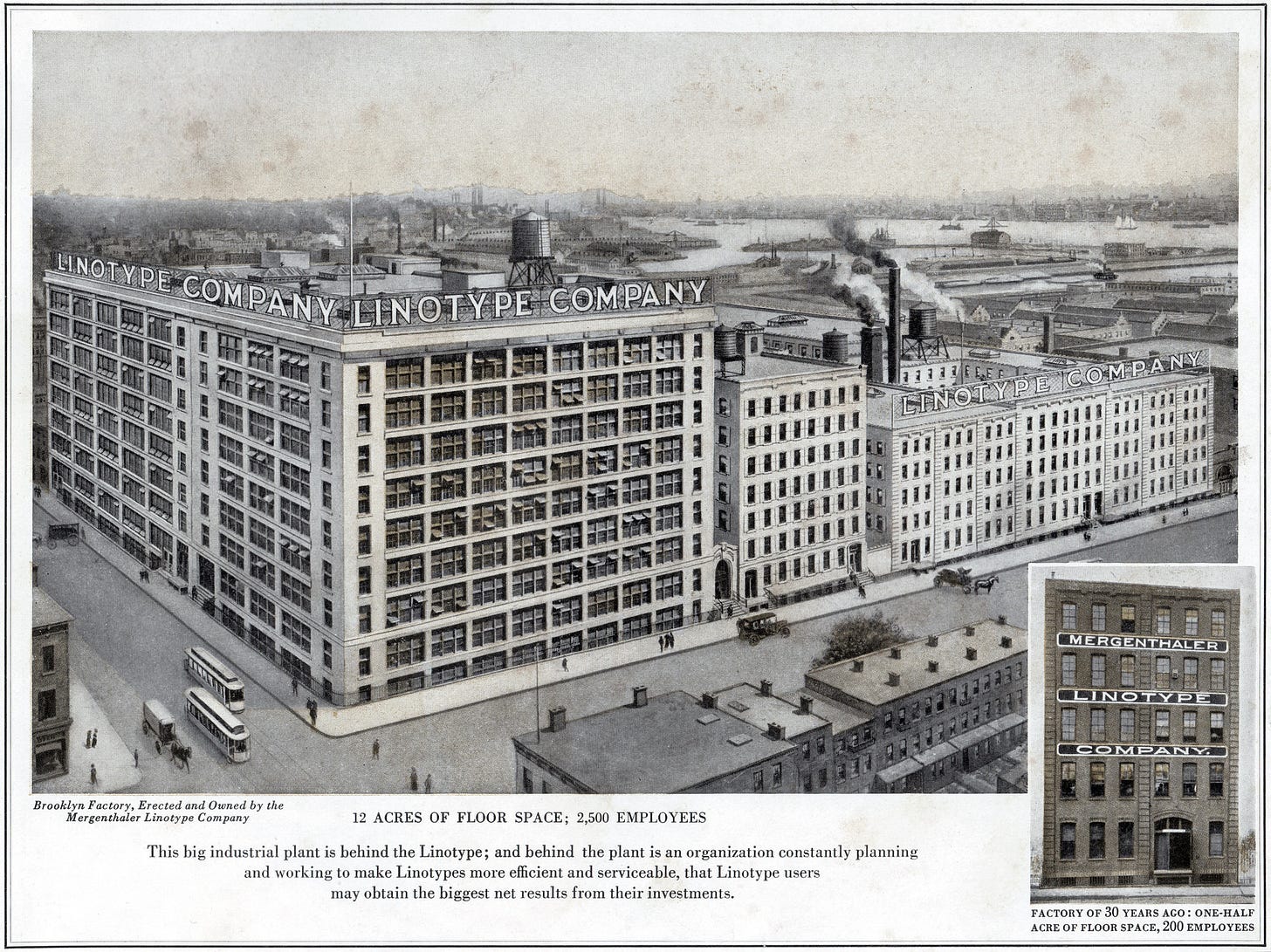

THE HALL

Walk two blocks east to Hall Street, and you will find yourself in front of the former home of the Mergenthaler Linotype Company, which used to manufacture typesetting machines. Today, it is New York City’s largest migrant shelter, with over 2000 beds spread over multiple floors.

In 2016, real estate behemoth RXR Realty purchased the building, kicked out the hundreds of artists who had their studios there, and began the process of turning the space, which they dubbed The Hall, into “a magnetic culture of collaboration and creativity, attracting premier talent and maximizing work-life integration, productivity, and purpose.”

Right after the completion of The Hall’s multi-million dollar renovation, Covid happened. The “authentic communities of makers, creatives, tech-visionaries, artists, architects, foodies, and change agents” never showed up. Instead, RXR’s investment hemorrhaged money until they were tossed a lifeline by Mayor Adams this past June. RXR was paid to convert some of the building’s floors into a “respite center” - the city’s name for what is supposed to be very short-term migrant housing.

In a particularly Orwellian twist, staffing at several of these respite centers, including the Hall, is provided by MedRite, the company behind the ubiquitous COVID testing sites found on every street corner during the height of the pandemic. Since these shelters are only meant to be temporary, migrants sleep within inches of each other, bathing facilities are minimal, and oversight is lax, which is understandable given that most of the staff’s previous job experience amounted to swirling a Qtip around people’s nostrils for a few seconds.

Some migrants decided they would be better off setting up tents underneath the adjacent BQE, though recent visits suggest they have been forced to leave.

I learned a ton from these two articles, so if you’re interested in reading more, check out these pieces in The City: New Migrant Shelter Expected To Become Largest Ever and The New Yorker: The Luxury Office Development That Became a Horrific Migrant Shelter.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio is mostly from around The Hall.

I experimented with making a 30-second exposure and a 30-second audio recording of both the Whitman house and the haunted Lefferts-Laidlaw House but decided those are better kept in the vault for now.

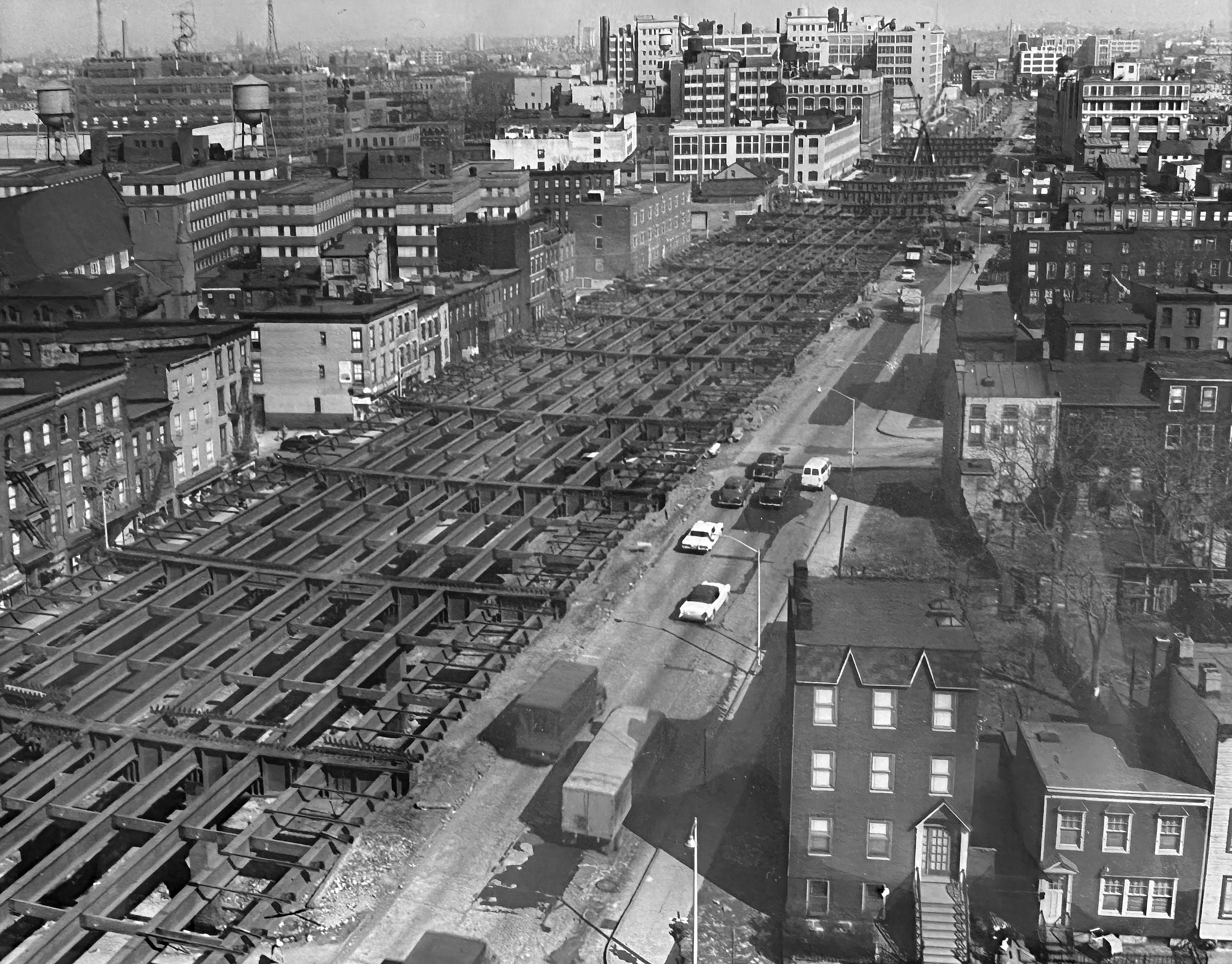

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPH

This week, I turned to eBay for a picture of Wallabout. Unfortunately I don’t know who the photographer is here*, but I have a bid in on the print and hope the seller can help me out. This picture shows the construction of the BQE in 1960, running right down Park Avenue in Wallabout. I thought I recognized that distinctive roof line in the foreground, and a quick search revealed the house was still standing at the corner of Park Avenue and Carlton.

*UPDATE: The photographer is Mal Gurian, who started his career taking pictures of Duke Ellington and Frank Sinatra for music magazines like Downbeat before enlisting in the Marines after the U.S. entered WWII. He parlayed his experience photographing during bombing missions into a business taking construction photographs. While on the job, he became interested in the CB radios construction firms used to communicate over big sites. This, in turn led him to start his own CB company. Gurian’s newfound expertise landed him a job at OKI Electronics Industry Company of Japan where he led the team that was credited for designing and manufacturing the first factory-made cell phones for Bell Telephone. Not a bad career trajectory from the son of a crane operator in the Bronx!

NOTES

If you find yourself in Wallabout, make sure to stop by Head Hi, an art and architecture-focused bookstore run by really lovely people that also happens to serve the best espresso in the neighborhood (and I’m not just saying that because they sometimes stock my book). I’m also a big fan of their no laptop/cell phone policy. While they have a thoughtfully curated selection of books ( how else would I have discovered Richard Wentworth’s Making Do and Getting By?), you can order any title, and they will have it in a couple of days. Unless, of course, you’d rather give your money to this guy.

If you’re hungry, you’ll find Wallabout’s version of Restaurant Row under the BQE. I’ve scarfed dozens of tortas de quesillo at GMC Temaxcal, and two doors down, Chef Sy at Tiger Box makes a great bibimbap. Both may be better as take-out options.

If you’re looking for a pre-Laffaholics bite, Petit Monstre is a fantastic vegan bakery also located in the former Rockwood factory. I’m not sure what the stand-up comedy fan/vegan sausage stuffed croissant eater Venn diagram looks like, but for the right crowd, it could be the perfect day.

https://www.nytimes.com/1878/12/20/archives/the-city-of-phenomena-ghosts-in-brooklyn-doorbells-rung-doors.html?scp=6&sq=%22edward+f.+smith%22&st=p

New Oxford American Dictionary (Second Edition)

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York · Monday, May 12, 1919

Turns out I used to live in Wallabout. I had no idea.

A chocolate river? Every kid's dream. I'm not surprised they quickly ganged around it.

That genuine New York street dialect in the newspaper story ("I know where there's a fine fire...") is a nice touch really missing from contemporary journalism.