I’ve had a hectic week and thought, why not make it easy on myself and feature a neighborhood that I have already photographed? The first place that came to mind was the Brooklyn Navy Yard, a ten-minute walk from my house and where I have had a studio for the past fifteen years. Perfect!

The problem is nobody lives in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, so, technically, it’s not a neighborhood. Hundreds of years ago, however, before the dry docks, WeWork cubicles, and artisanal breweries, it was one of Brooklyn’s oldest neighborhoods, Wallabout. Maps still refer to the two blocks between the Navy Yard and Myrtle Ave as Wallabout, even if nobody who lives there does.

Since the Navy Yard has such a rich history, I decided to dedicate this week’s newsletter exclusively to it and will follow up with Wallabout proper for the next edition (in two weeks). This will be the first official 2 part post in The Neighborhoods. The excitement is palpable.

THE ADAM AND EVE OF NEW NETHERLAND

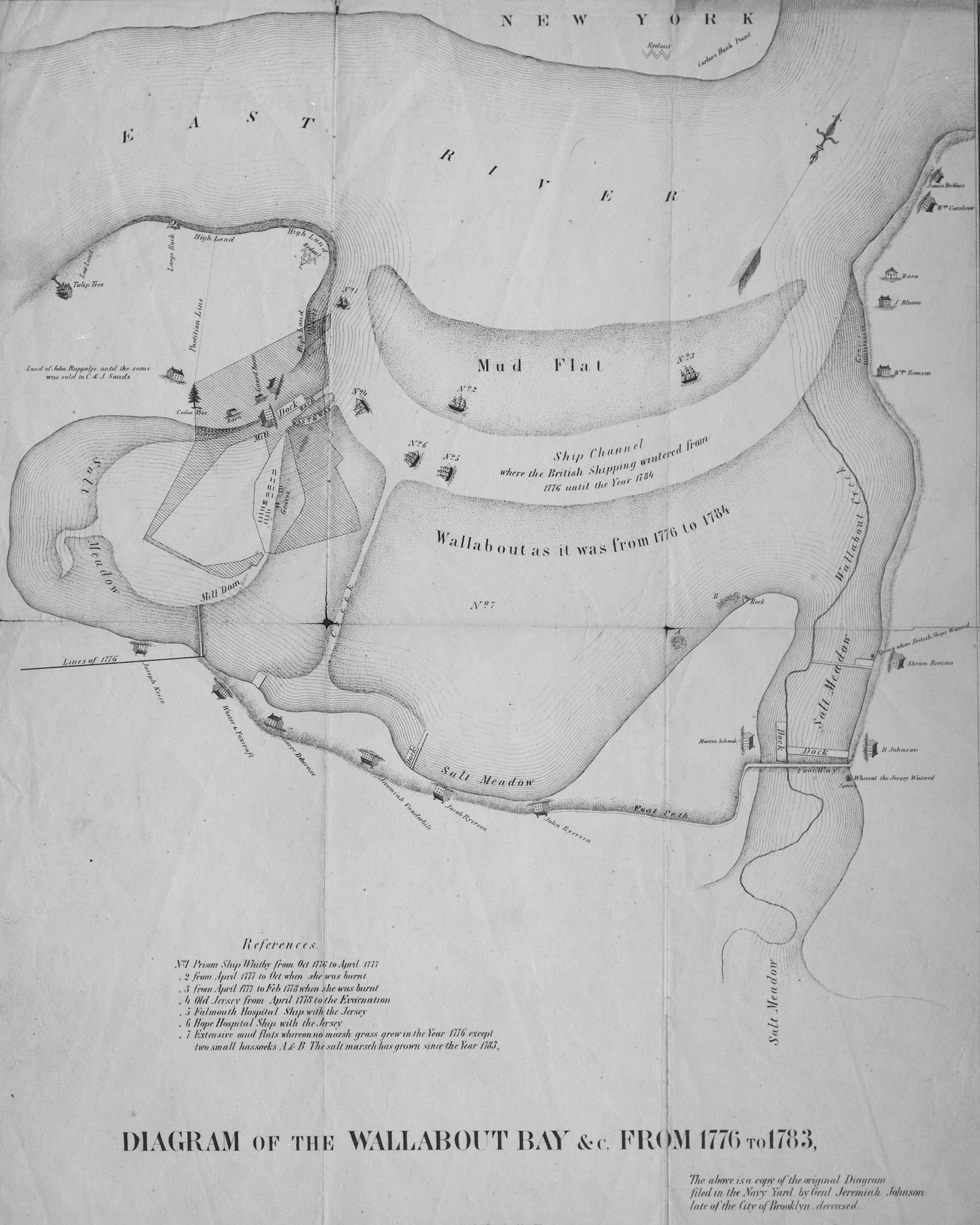

In the 17th century, a group of Walloons settled along a bay on the Brooklyn side of the East River near the mouth of New York harbor. The new settlement was called “Waal-bogt,” meaning either “Walloons bend” or “bend in the harbor,” depending on which etymologist you trust.

Joris Jansen Rapelje, the first European settler in the area, built his house on the 335 acres he had bought from the local Canarsie Indians. Russel Shorto, in his history of early New York, called Joris and his wife, Catalina, the “Adam and Eve” of New Netherland. Their over one million descendants include Humphrey Bogart, Tom Brokaw, Howard Dean, and Joseph Hoagland, who co-founded the Royal Baking Powder Company with our old friend William Ziegler of Malba fame.

Wallabout remained primarily a farming community for the next 140 years.

GHOST SHIPS

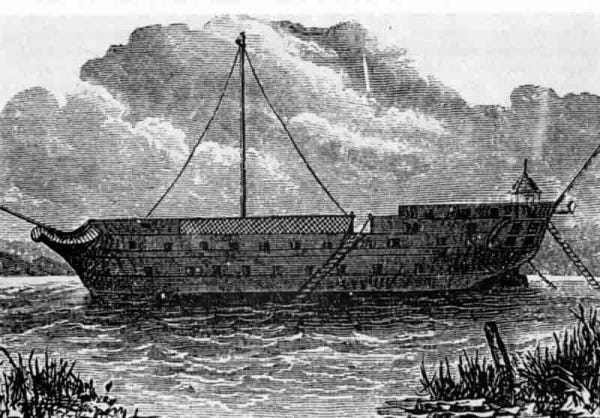

During the Revolutionary War, the British, who had established a stronghold in New York City, ran out of room in the sugar warehouses they had been using for captured soldiers, so they moved their prisons offshore. Thousands of rebel soldiers and sailors were imprisoned aboard sixteen “floating dungeons” that were moored in the fetid waters of Wallabout Bay.

“The black ship like a demon state, Upon the prowling deep, from her came fearful sounds of hate, till pain stilled all in sleep It was the sleep that victims take, Tied, tortured dying at the stake.”

These converted vessels, packed to the gunwales with the malnourished and diseased bodies of their captives, were used as a psychological weapon, a reminder of the consequences of taking up arms against the Crown. Over 11,000 died in the squalid conditions aboard the ships, nearly double the amount of soldiers who died in action during the entire war.

When dead bodies were discovered, a feat that sometimes took several days, they were dumped into shallow holes dug in the mud flats of the bay. Or they were simply thrown overboard. According to historian Edwin G. Burrow, for years afterward, bleached skulls littered the coast “as thick as pumpkins in an autumn cornfield.”

BROOKLYN NAVY YARD

In 1801, the US Government, under the orders of President John Adams, purchased 40 acres of the old Rapelje farm to create one of 5 naval yards in the country.

During its 160-year run as a shipbuilding center, the Brooklyn Navy Yard repaired and built boats used in the War of 1812, the Civil War, and both World Wars. The USS Maine and the USS Arizona, a battleship destroyed in the attack on Pearl Harbor, are among the hundreds of boats built in the yard.

In its heyday, the years before and during WWII, the yard employed over 70,000 people. During this time, the Navy Yard earned the nickname the “Can-Do Shipyard,” though it “couldn’t have done” much if not for the contributions of a newly enlisted female workforce. For the first time in its 143-year history, the Navy Yard deigned to hire women to fill the positions vacated by male workers who were off fighting in the war.

Thousands of women, earning half of what their male counterparts were paid, were employed as pipefitters, welders, truck drivers, and electricians.

In Jennifer Egan’s novel Manhattan Beach, the book’s protagonist, Anna Kerrigan, spends her days working at the Navy Yard.

In the rich late-October sunlight, the Naval Yard arrayed itself before her with the precision of a diagram: ships of all sizes berthed four deep on pronglike piers. In the dry docks, ships were held in place by hundreds of filament ropes, like Gulliver tied to the beach. The hammerhead crane brandished its fist to the east; to the west loomed the building ways cages. Around all of it, railroad tracks spiraled into whorls of paisley.

WALLABOUT MARKET

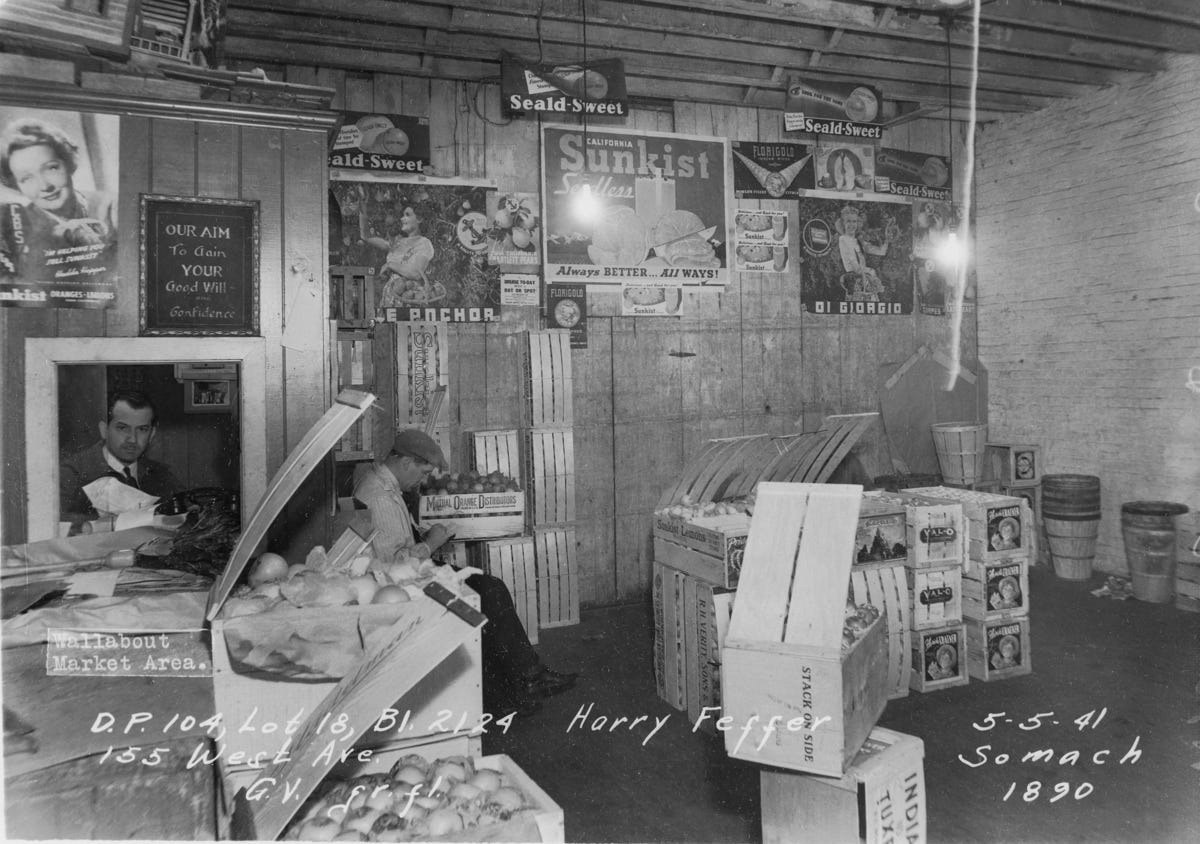

In 1884, Wallabout Market, the second-largest wholesale market in the world, was built adjacent to the Navy Yard. The bustling market was full of produce stands, butcher shops, fishmongers, and everything else a grocery store or restaurant could need. It was also a popular spot for the ne'er-do-wells, shakedown men, and scallywags who frequented the darker corners of the complex.

Besides its immense size, the market’s most notable aspect was its unique Flemish Revival style architecture, designed by famed Brooklyn architect William B. Tubby. The stepped roofs and fantastical decorative spires are a nod to the area’s Dutch roots.

I love this series of photos from the National Archives taken a few months before the largely vacated market closed.

By the 1940s, WWII was in full swing, and the Navy needed space to build and repair more ships. The adjacent market, with its bustling population and open gates, was deemed a security threat and was taken over by Navy Yard, who demolished Tubby’s fairy tale creation in 1941.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction

In 2016, Admiral’s Row, a stately row of ten homes built in the late 19th century for naval officers in the Navy Yard, was demolished and replaced by a Wegman’s supermarket.

FROM BOATS TO BEYONCE

By 1965, twenty years after the end of the war, fewer than 7,000 people worked at the shipyard, and in 1966, the facility was decommissioned. After twenty years of shuttered businesses and vacant buildings, the yard began to go through a renaissance of sorts. Today, the complex, reclassified as an industrial park, has a workforce of roughly 11,000 people. While there is still an active shipyard with its rusted blue cranes occasionally gliding noiselessly above the dry docks, most businesses have little to nothing to do with the maritime industry.

All over the yard, buildings are being renovated and repurposed, including the Newlab, once a crumbling ruin so picturesque that I used it as the backdrop for both a prog metal band and a lucha libre photo shoot, today one of the Navy Yard’s most modern buildings, with its own indoor temperate rainforest. The tech hub minces no words in its mission statement:

In 2016, conventional wisdom understood the diversity, density, and adversity of a city like New York to be an impediment to innovation, rather than a powerful reagent for the technology of the next industrial revolution. We called bullshit.

We erected Newlab from the ruins of a turn-of-the-century naval shipyard in Brooklyn because we knew that from adversity and diversity comes invention. And we saw the need for something new: A place for the people crazy enough to build hardware in NYC to find the tools, space, and community to supercharge their ambition and create a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable world.

Ok, settle down Newlab.

Other adaptive reuse projects include the Duggal Greenhouse, a former shipbuilding warehouse turned event space that has been used by Beyoncé for rehearsals, by Alexander Wang for the debut of his 2014 fall collection, and by the DNC for the 2016 primary debate between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton.

The building I work in, the glamorously named Building 3, is filled with high-end woodworkers, an online record store, a rooftop farm, and even a spacesuit manufacturer.

The Navy Yard also boasts its own distillery, a rooftop vineyard, and Steiner Studios, the largest film studio outside of Hollywood, sitting on the land formerly occupied by the Wallabout Market.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

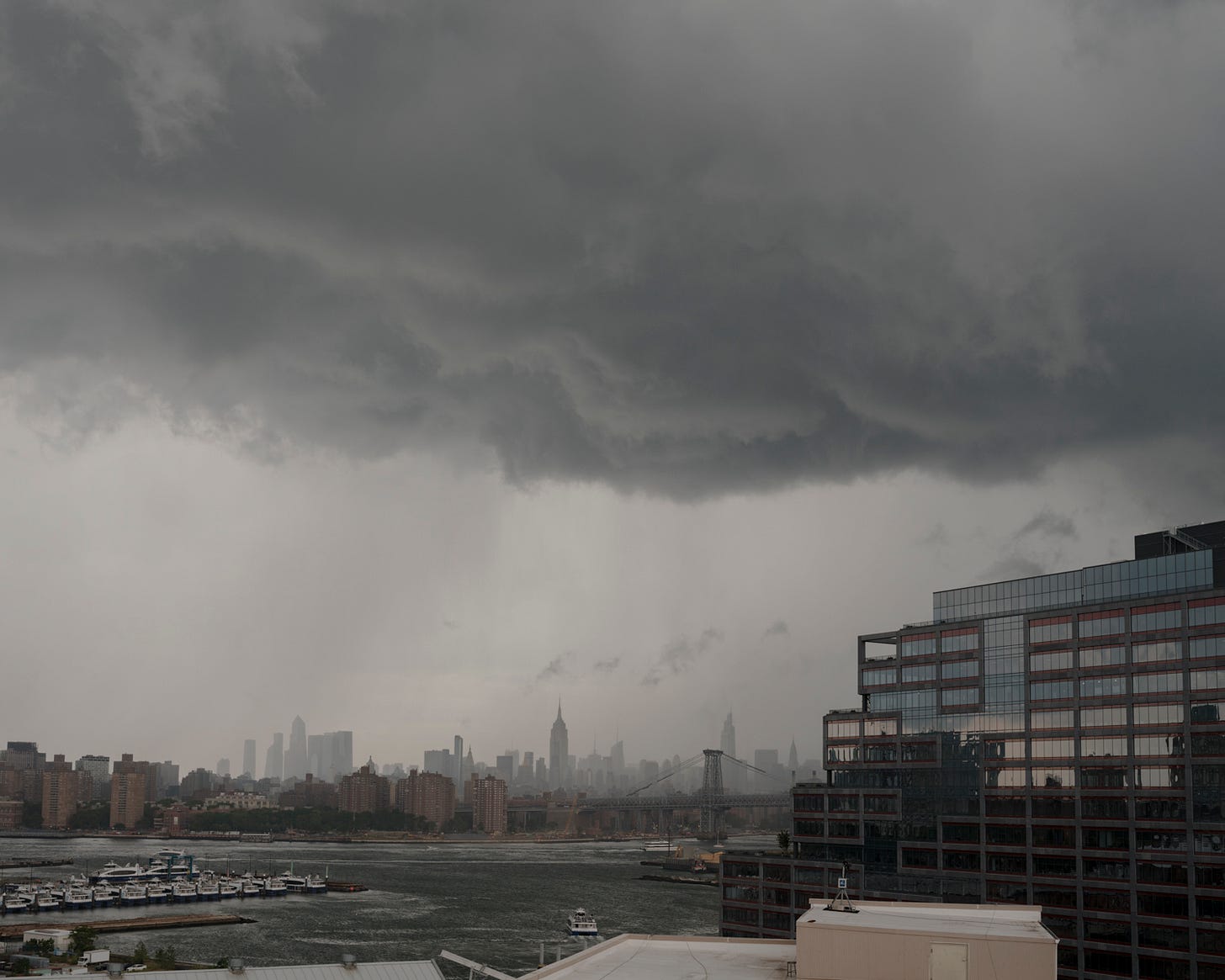

I was really hoping to capture some intense nautical sounds for this week’s field recording: a foghorn, some creaking pylons, maybe some rope coiling. But I guess the maritime days are largely a thing of the past. I did manage to capture some occasional creaks and escapes of steam, though.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

The Navy Yard is hard to access if you don’t work there, so many New Yorkers only know it through photographs. My favorite images from the area were captured by architectural photographer John Bartelstone who made an excellent body of work,The Brooklyn Navy Yard, published by powerHouse Books in 2010. Starting in 1994, Bartelstone’s photographs, made with an 8x10 view camera, captured the Navy Yard as it shifted its focus from the maritime industry to the tech industry.

All photos below ©John Bartelstone

NOTES

Two hundred forty years after the floating dungeons sank to the bottom of Wallabout Bay and 8 miles up the East River, the Vernon C. Bain Center, an eight-hundred-person floating jail docked near Rikers Island in the Bronx, finally closed its doors. It was the only prison ship in the country. The jail was meant to serve as a temporary solution to overcrowding when it was put into service in 1992 but has remained in operation until just this month. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it was repurposed into a floating migrant shelter.

In his 1951 profile of the NY Harbor for the New Yorker, Joseph Mitchell wrote about the surfeit of corpses still bobbing to the surface of the bay, so many in fact that the police had to fashion a net out of tire chains to skim the water for the inevitable surge bodies that appeared with the warming of the water every spring.

This backwater is called Wallabout Bay on charts; the men on the dredges call it Potter's Field. The eddy sweeps driftwood into the backwater. Also, it sweeps drownded bodies into there. As a rule, people who drown in the harbor in winter stay down until spring. When the water begins to get warm, gas forms in them, and that makes them buoyant, and they rise to the surface. Every year, without fail, on or about the fifteenth of April, bodies start showing up, and more of them show up in Potter's Field than any other place. In a couple of weeks or so, the Harbor Police always finds ten to two dozen over there- suicides, bastard babies, old barge captains that lost their balance out on a sleety night attending to tow-ropes, now and then some gang-ster or other.

The best way to visit the Navy Yard, and the best way to get around New York, is to take a ride on the NYC ferry. It gets you past security and you can get a bite at the Brooklyn outpost of legendary New York bagel and lox spot Russ and Daughters (leave plenty of time).

This was such a thorough dive into the history of the Navy Yard. Thank you, Rob, and the photos are fantastic.

Great post. I became fascinated with the Navy Yard after reading Jennifer Egan's Manhattan Beach which somehow made all that industry seem romantic - and this adds to it! Seeing the Concorde while getting on the ferry back in September was a very groovy surprise.