Last week, looking for inspiration on my next neighborhood, I perused the listings for Open House New York, the city-wide festival that “promotes unparalleled access to the city.”

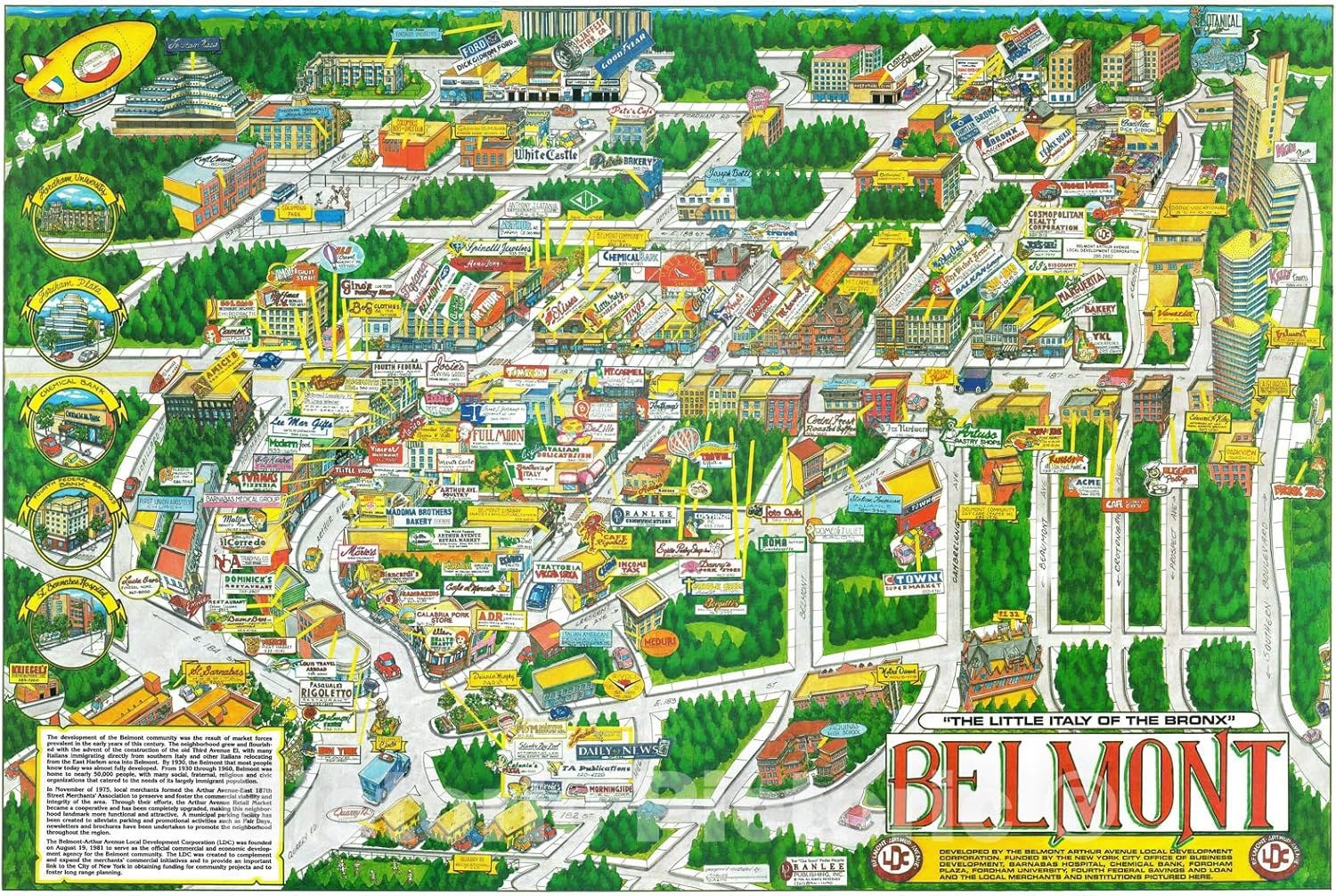

While there weren’t many offerings in the Bronx (next up in my borough rotation), an exhibition of topographical maps at Fordham University seemed right up my alley. I spent a few hours before the exhibition walking around the neighborhood of Belmont on the university’s southern edge.

Arthur Avenue, the neighborhood’s main drag, is lined with enough bakeries, salumerias, and red checkered tablecloths to give Manhattan’s diminutive Little Italy an inferiority complex. Or, as Sam Grobart savagely wrote in New York Magazine, “The restaurants of Arthur Avenue make Mulberry Street’s look like stepchildren of the Olive Garden.”

But venture one or two blocks off of the avenue, away from the rows of double-parked Escalades (Jersey plates), with nothing but the faintest scent of soppressata in the air, and you are in a whole different neighborhood. Despite the abundance of Arthur Avenue, Belmont is one of the poorest neighborhoods in the Bronx, itself the poorest borough in the city.

While it’s hard to square these two versions of the neighborhood, geographically at least, Belmont is easy to grasp. It’s just eight blocks by nine blocks. The Bronx Zoo is to the east, East 181st Street is to the south, Fordham Road is to the north, and the Metro-North Harlem Line is to the west.

UP TO SNUFF

The name Belmont comes courtesy of Pierre Abraham Lorillard, a French Huguenot who came to New York in 1760. Pierre got his start apprenticing as a snuff-maker, and when he was just 18 years old, he started his own operation, the Lorillard Tobacco Company.

Lorillard set up shop on Chatham Street in Manhattan, where he dried, ground, and packaged his snuff in dried animal bladders. His company stayed in business for another 264 years, producing some of the first brand-name tobacco items—Climax, Sailor's Delight, Catawba, Red Cross, and Green Turtle.

Snuff, if you didn’t know, is a finely ground tobacco that people typically inhale through their nose. In the 18th and 19th centuries, snorting was somehow seen as more refined than smoking, which was considered uncouth.

Queen Charlotte, who was given the not-so-flattering nickname “Snuffy Charlotte,” was such a fan of the stuff that she had an entire room at Windsor Castle dedicated to her snuffing pursuits.

Not to be outdone was Miss Margaret Thompson of Westminster, whose unflagging devotion to the “sneezeweed” was evidenced in her will.

“I also desire that all my handkerchiefs that I may leave unwashed at the time of my disease be put at the bottom of my coffin, which I desire may be large enough for that purpose, together with such a quantity of the best Scotch snuff as will cover my deceased body.”

She goes on to stipulate that her six pallbearers, “well known to be the greatest snuff takers in the parish of St. James,” wear snuff-coloured beaver hats and that during the procession, large handfuls of snuff should be tossed every 20 yards on the ground and to the crowd.

You have to wonder what it takes to earn the title of greatest snuff taker in the parish.

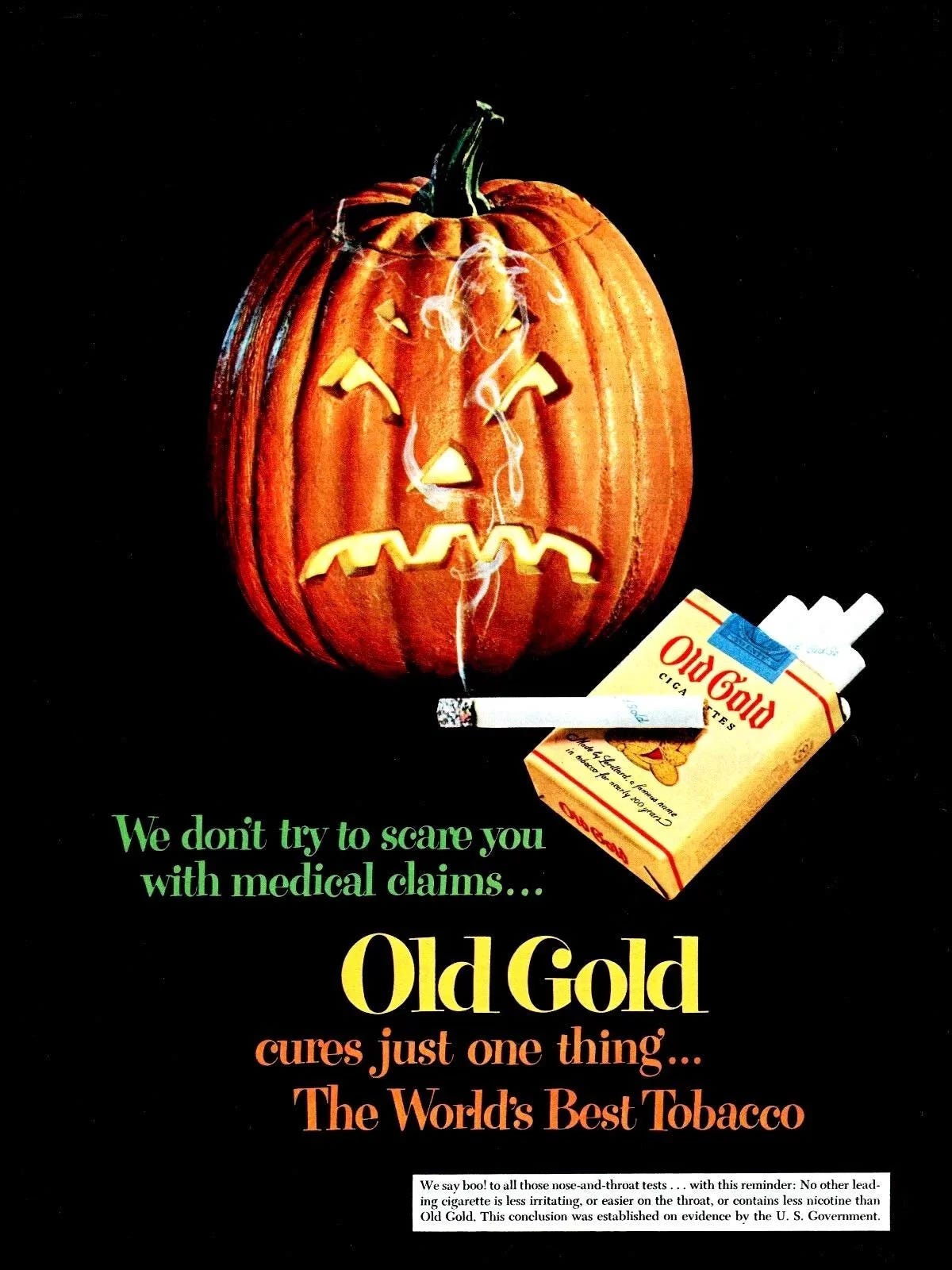

Snuff eventually fell out of favor as cigarettes became the preferred tobacco delivery system. By then, though, the Lorillard company had pivoted, manufacturing brands like Newport, Kent, and Old Gold, which were apparently quite good for you.

Lorillard died at the age of 34 during the American Revolutionary War. In 1792, his sons moved the operation to the country, purchasing a grist mill on the banks of the Bronx River.

The family acquired much of the surrounding land for their estate, which they called “Belle Mont.” The snuff-grinding mill, rebuilt out of stone in the 1800s, still stands in the Bronx Botanic Gardens. You can even get married there if you want.

If you are interested in getting married, make sure you think long and hard about your Match.com profile picture.

After the Civil War, the company moved its manufacturing operation to New Jersey, foreshadowing the later migration of Italians out of Belmont in the 20th century.

Catherine Lorillard Wolfe, Pierre’s great-granddaughter, inherited the vast estate and divided it up for sale. She donated the Lorillard mansion to the Home for Incurables (now St. Barnabas Hospital). The eastern part of the estate would turn into Bronx Park, home to the New York Botanical Garden and the Bronx Zoo.

LITTLE ITALY

The zoo catalyzed Belmont’s transformation into an “Italian Colony.” Between 1880 and 1920, in what was called the Great Arrival, over 4 million Italian immigrants came to the US. Many of those seeking employment found it at the zoo, which required large numbers of laborers to build the animal houses and landscape the extensive grounds. The extension of the elevated train along Third Avenue to the neighborhood's edge further spurred development.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Belmont was bustling. Arthur Avenue (named after Catherine Lorillard’s favorite president, Chester Arthur) was the center of the action. Pushcarts, bursting with piles of eggplants, tomatoes, squid, bacalo, sardines, and fresh mozzarella, lined the street.

Eventually, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia put an end to the “pushcart evil,” branding them an unsanitary and underregulated public nuisance. He used WPA funds to open several indoor markets. The Arthur Avenue Retail Market opened in October 1941, joining similar markets like the Essex Market in Lower East Side and the Thirteenth Avenue Retail Market in Boro Park.

Today the market is thriving with nine restaurants, five pastry shops, four butchers, two pasta-makers, six bread stores, three pork stores, five gourmet delicatessens, two fish markets, three gourmet coffee shops and a cigar maker.1

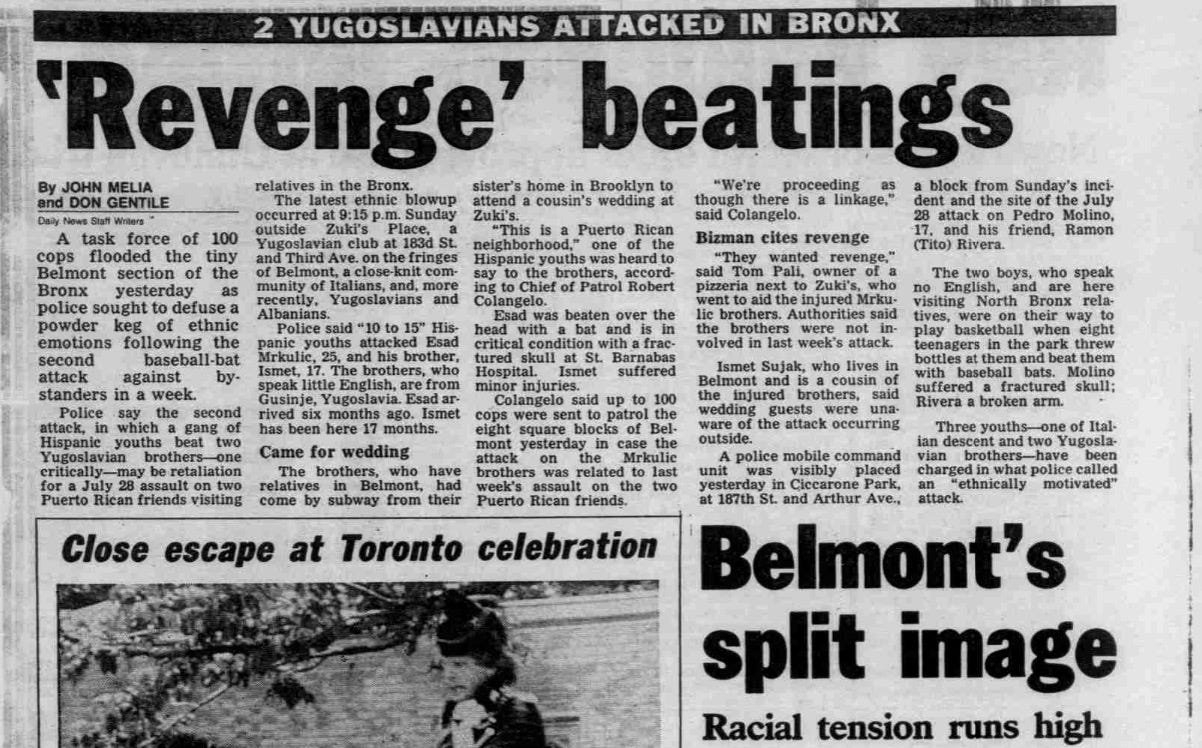

A powder keg of ethnic emotions

Belmont largely weathered the turmoil that gripped most of the South Bronx in the 70s and 80s. The neighborhood policed itself.

Officer Edward Walsh, who has been assigned to Belmont for 15 years, said that during the 1978 blackout, there were break-ins and looting on Fordham Road, just blocks from the neighborhood, ''but here, there wasn't so much as a window broken.''

Part of that policing invariably involved keeping “others” out. In the 1970s, according to Mark Naison, Professor of African American Studies and History at Fordham University, busses full of students coming from the South Bronx on their way to Roosevelt High School had to be rerouted from Arthur Avenue because people threw rocks at them.2

Beginning in the 1980s, large numbers of Albanian and some Yugoslavian immigrants started to settle in the neighborhood. By this point, at least some of the original Italian inhabitants of Belmont had decamped for the suburbs of New Jersey and Long Island.

While a Federal survey in 1983 rated Belmont one of the safest neighborhoods in the country, it was still not immune from crime and violence.

Two incidents in the summer of 1986 brought the neighborhood to a boiling point. On July 28, eight white youths armed with baseball bats beat two Puerto Ricans who were walking along Arthur Avenue near East 188th Street. Six days later, a group of Puerto Rican and Black youths jumped two Yugoslav brothers in supposed retaliation. The attacks set off what the Daily News called a “powder keg of ethnic emotions.” For the next few weeks, over 200 police officers patrolled the neighborhood’s eight blocks.

Six years later, in 1992, a 35-year-old Puerto Rican man was beaten to death by a mob of 15 white men a few blocks from the 1986 incident. After a fight with a drug dealer, a woman told a group of men in a social club that a Latino man had attacked her. A group of men rushed out, and the first person they saw was Puerto Rican Carmelo Rivera. As the mob kicked and punched Rivera, the woman yelled, "It's not him!"3

Locals on all sides, including Rivera’s sister and mother, were quick to say that the incident was not racially motivated and instead was a case of mistaken identity.

People who live here and work here are still paying for what happened in 1986 to this day. They point the finger at the Italian-Americans right away and try to make it out to be another Bensonhurst. It kills business and it makes matters so much worse.4

While the beating may not have been overtly racially motivated, it did lead to “some soul-searching among the long-term residents and the newcomers about how well they coexist.” The incident also highlighted the neighborhood’s growing drug and crime problem.

It took over a year to arrest some of the perpetrators, including George Mazzone, who was found at a Beverly Hills house that his friend had been renting from singer, flamenco guitarist, and semiregular Hollywood Squares panelist Charo.

Eventually, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and other Latinos, as well as African Americans, settled down in the neighborhood. Today, you are just as likely to find some tacos de birria or warm slices of leçenik as you are plates of caico e pepe.

Perhaps most indicative of the neighborhood’s demographic shift is the schedule of Masses at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, the Roman Catholic parish in the heart of Little Italy. The church offers a Spanish Mass every weekday and two on Sundays. There is only one Mass still offered in Italian.

OH BOYA

Walking around Belmont the other day, I spotted an AC unit propped up by a small can of Goya coconut milk. I immediately stopped to take a picture. These kinds of small adaptations, somewhat strange but practical interventions, always catch my eye.

About 20 minutes later, I spotted another one.

Two occurrences are a coincidence. Three? That’s a movement. At this point, my eyes were finely tuned, darting from window unit to window unit. When you are looking with purpose, even for something as obscure as an old can of Goya wedged under an AC unit, your search will often be rewarded.

So Close.

Success! I am now accepting preorders for my forthcoming coffee table book, AC Units Propped up by Cans of Goya.

Just as I was wrapping up, I found an outlier:

This faded 28-oz can of Victorina Tomato Paste, my first non-Goya sighting, signified a subtle shift from sofrito to marinara. Maybe a rigorous survey of the different types of cans used to prop up a neighborhood's air conditioners could be used to chart the arc of its demographic transitions over time. Maybe it was just a coincidence.

For more pointless projects, see

’s post Pointless Projects.SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio starts with a snippet from the map exhibition at Fordham University (with an incongruous Downtempo soundtrack) before finishing off with two different sidewalk preachers and a saxophone busker.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Photojournalist Arthur Rothstein spent several years working on the federally sponsored Farm Security Administration (FSA) photojournalism project, which was the “first attempt by the federal government to provide a broad visual record of American society.”

The FSA employed a small group of photographers, including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks, to document and depict life in the United States during the Depression era.

Here are some of his photos from a 1936 series simply titled Scene from the Bronx Tenement District from Which Many of the New Jersey Homesteaders Have Come. While Washington and Bathgate Avenues are both major thoroughfares in Belmont, looking at the architecture and signage, I suspect these pictures were taken just a bit further south in Crotona.

ODDS AND END

There was a bit of a snuff-aissance within a certain subset of 7th-grade boys in my middle school. At the time, everyone was hooked on those Vicks inhaler sticks, which proved to be the perfect gateway drug to the snuff big leagues.

.

I can guarantee you will see no better video this week than this short “You Asked For It” piece on the 1980 World Snuff Championships in Wellington, Somerset. Full of cringey snuff puns, questionable facial hair choices and a tour de force demonstration of speed snuffing prowess by reigning world champion, Larry Popp.

This compilation of scenes from the short-lived TLC reality series Mama's Boys of The Bronx makes you wonder why the show only lasted two episodes. You can follow along as five Italian American men in their thirties work on “looking good, living large, and chasing girls,” all while living with their mothers.

Novelist Don DeLillo grew up in Belmont, on the corner of 182nd Street and Adams Place. I love this passage from his 1997 novel Underworld, which takes place in his old neighborhood.

Bronzini thought that walking was an art. He was out nearly every day after school, letting the route produce a medley of sounds, forms, and movements, letting the voices fall and the aromas deploy in ways that varied, but not too much, from day to day. He stopped to talk to card-players in a social club and watched a woman buy a flounder in the market.

He watched an aproned boy wrap the fish in a major headline. Even in this compact neighborhood, there were streets to revisit and men doing interesting jobs—day laborers, painters in drip coveralls, or men with sledgehammers he might pass the time with, Sicilians busting up a sidewalk, faces grained with stone dust.

Eater put together a list of Arthur Avenue’s best eateries.

Doo Wop superstars Dion and the Belmonts got their start in the neighborhood.

A Bronx Tale, the 1993 American drama directed by and starring Robert De Niro, is based on writer and actor Chazz Palminteri’s life growing up in Belmont.

https://www.arthuravenuebronx.com

https://medium.com/@eliotschiaparelli/education-levels-in-belmont-2d38f9c65c5

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/08/23/nyregion/in-wake-of-death-belmont-shuns-talk-of-race.html?ogrp=ctr&unlocked_article_code=1.Uk4.Dedw.lCTqRDCAphHD&smid=url-share

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/08/23/nyregion/in-wake-of-death-belmont-shuns-talk-of-race.html?ogrp=ctr&unlocked_article_code=1.Uk4.Dedw.lCTqRDCAphHD&smid=url-share

Having decamped to the Left Coast some years ago, I try to explain to Angelenos the quirky and adaptable side of New Yorkers, and how we always find a way to get things done. Those Goya cans under the A/C window units are a perfect example of five borough ingenuity that you'd be hard pressed to find anywhere else. Great post Rob, as always.

So much to like in this post, the history (snuff!), racism 😢, Goya cans plus an outlier, and the pictures of the city. Specially love the trees, and there are two flanking a Tesla Cybertruck, what a combination! Also the End sign or sometimes Stop sign, I look for that each time, signifying the formal end of each piece. But please don’t take this as pressure to always have a photo of an End sign 😅, just whatever catches your eye in any place 😍