Perched atop a rocky escarpment in the west Bronx, Highbridge presides over the concrete contortions of the Major Deegan and Cross Bronx expressways, a pretzel logic of overlapping loops and arteries that ferry commuters over the Harlem River into Manhattan. The neighborhood gets its name from its most recognizable landmark and New York City’s oldest bridge, the High Bridge, built in 1848 as part of the Croton Aqueduct.

Highbridge, originally part of a larger area in the Bronx called Keskeskeck by the Lenape Indians, was also known as “Nuasin,” which means “the land between.” In this case, "between" referred to the land bounded by the Harlem River and Cromwell’s Creek, which was buried and paved over in 1906. Jerome Avenue, which follows the creek’s path, serves as the neighborhood’s southwest border. Highbridge’s other borders are the Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95) and the Edward Grant Highway. Yankee Stadium is situated just across the neighborhood’s southern border in Concourse.

WATER

During last week’s look at Springfield Gardens, I mentioned how the less-than-salubrious water provided by the Brooklyn Water Works aqueduct was a major factor in Brooklyn’s decision to incorporate with New York City in 1898.

Years before, Manhattan had its own water issues to contend with. The city’s ponds, springs, and wells, once a reliable source of drinking water, had become fouled by unchecked dumping of chemicals and sewage. This pollution led to outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera, and the scarcity of water made it impossible to contain the destructive fires that periodically ravaged the city.

“What made New York a prosperous port – its deep saltwater rivers – made its drinking water lousy. By the middle of the eighteenth century, Manhattan’s water was already infamous: there was too little of it, and what little there was tasted terrible.”

Jill Lepore

In 1837, construction began on the Croton Aqueduct, a massive project that would eventually bring fresh water over 40 miles from the Croton Reservoir in upstate New York to the city. Nearly four thousand workers, most of them Irish immigrants, completed the project in just five years. The aqueduct’s gravity-fed design required only a 1/4-inch drop every 100 feet to keep the water flowing toward the city.

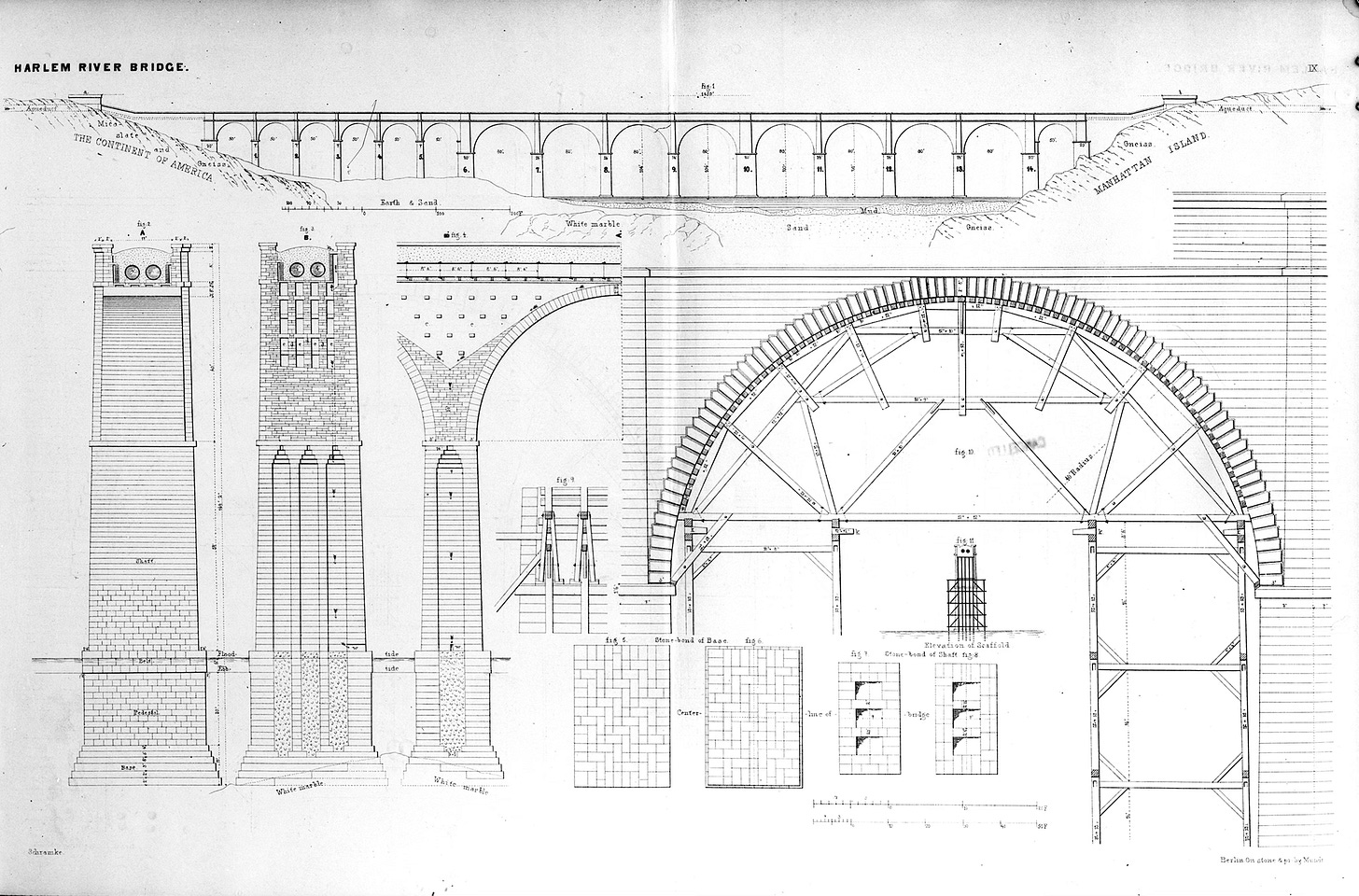

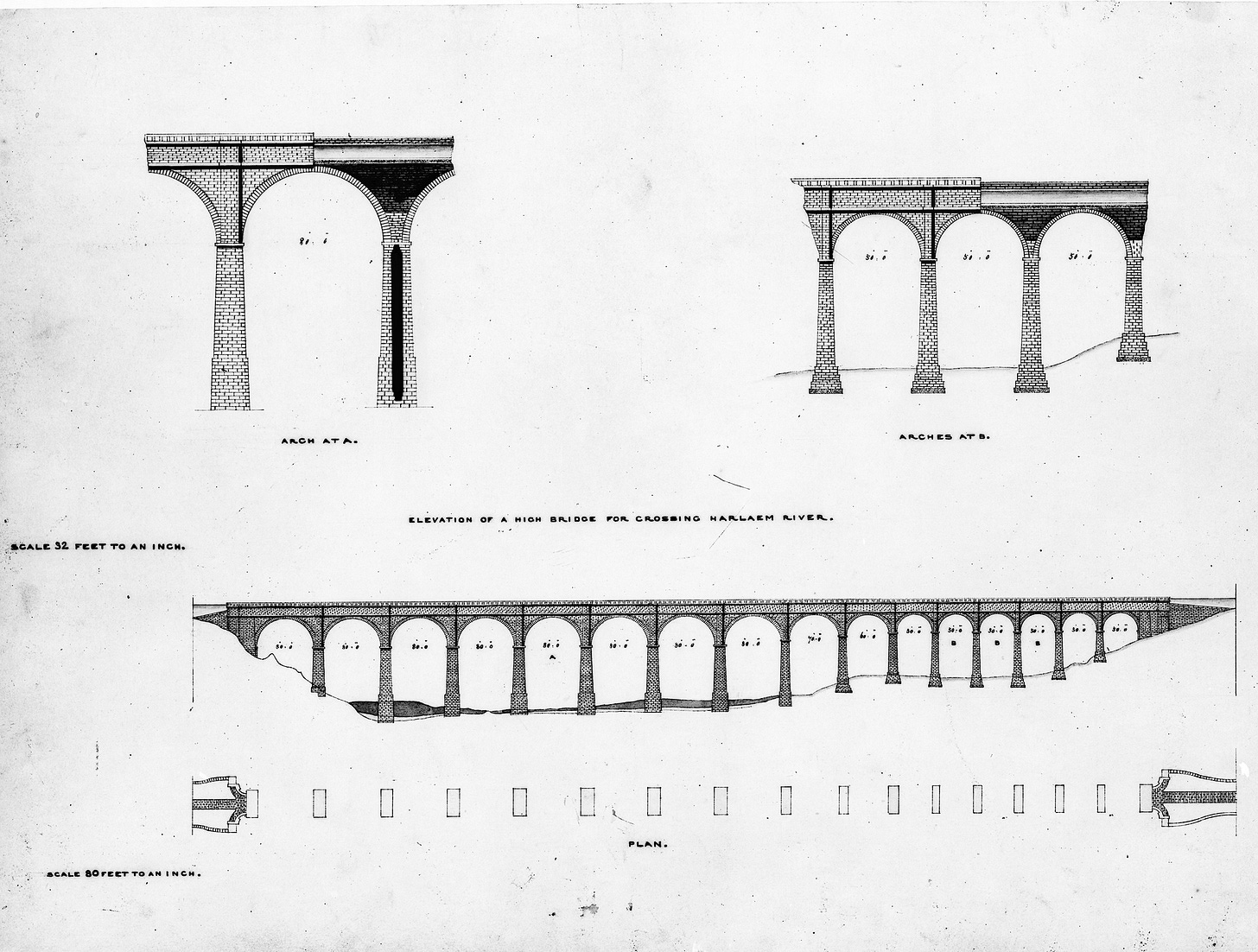

One of the challenges faced by the project’s engineers was how to get the water across the Harlem River into Manhattan. After scrapping plans for a tunnel, they decided to build a bridge. Since the river was used to bring goods in and out of the city, anything that impeded navigation was out of the question, so they made it high.

The project's chief engineer, John Bloomfield Jervis, modeled the 140-foot-tall High Bridge, with its fifteen masonry arches, after the Roman aqueduct bridges.

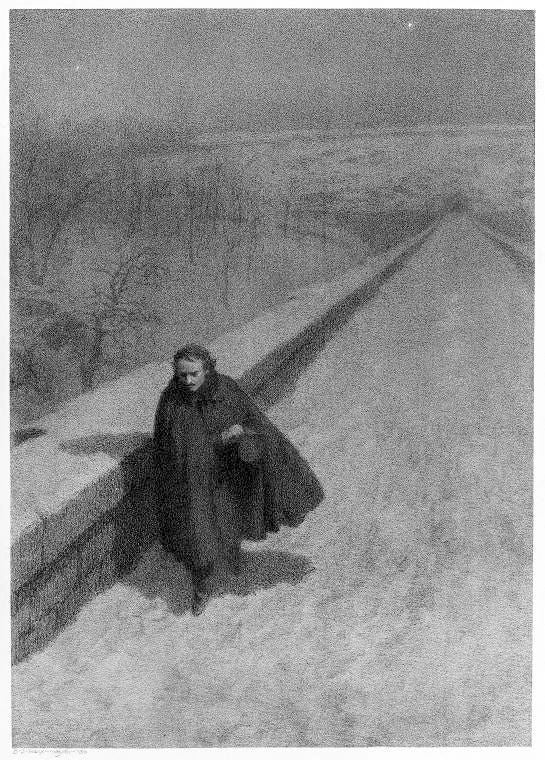

The bridge was completed in 1848, though the public walkway on top didn’t open until nearly 20 years later. That didn’t stop Bronx resident and master of the macabre Edgar Allan Poe. In the year between the bridge’s opening and his death, it became “a pacing and thinking place for Poe, who, day or night, might be spotted on the grass causeway at the top of the lofty structure.”

The engineers originally believed that the 90 million gallons of water the aqueduct delivered per day would be enough for the next century. The rapidly growing city, however, proved to have an unquenchable thirst. In 1885, construction began on the New Croton Aqueduct, which was engineered to provide nearly four times as much water as its predecessor. Today, New Yorkers consume a staggering 1 billion gallons of water each day.

In 1928, five of the masonry arches that spanned the river were replaced with a single steel arch to make the river safer and easier to navigate. The bridge stopped carrying water after 1949, and following years of neglect, the pedestrian promenade closed in 1970.

Thankfully for Edgar Allan Poe fans and anyone who loves a short walk on a high bridge, the walkway was reopened to the public in 2015.

LESLIE

When the walkway first opened, several restaurants and beer gardens followed suit, taking advantage of the influx of new visitors to previously sleepy Highbridge.

One of those establishments, Kyle’s Park Dance Hall, just north of the High Bridge, thought of a unique way to differentiate themselves from the competition. Though you may think a place that offers music, dancing, and ice cream wouldn’t need to resort to gimmicky promotions, Kyle knew better.

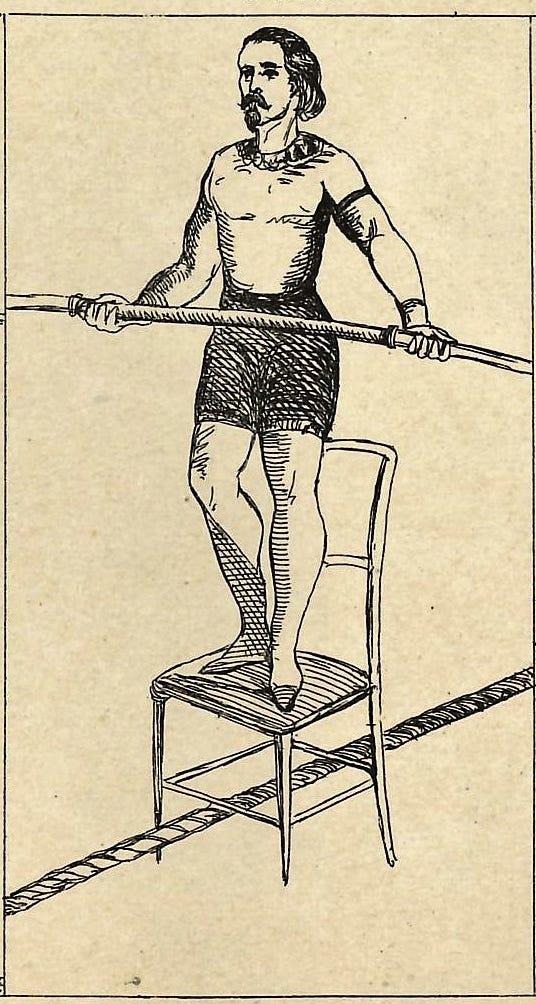

When word got out that a tightrope walker, known simply as Leslie, was going to walk across the Harlem River, crowds began to gather. Those lucky enough to attend would be treated to a spectacle that made Philippe Petit’s exploits look downright pedestrian.

Leslie started on the Manhattan side of the river. At the midpoint of his walk, on a thin hemp rope quivering above the river, he took off the small portable stove strapped to his back, lit it, and began to cook pancakes. When they were cooked to perfection, Leslie dropped the pancakes down to crowds of spectators floating in rowboats below. Those boaters must not have been able to believe their luck when the funambulist’s fluffy flapjacks began raining down upon them from above.

I know what you’re thinking- funny story, but fat chance. I was a little skeptical myself until I learned of Charles Blondin, aka The Great Blondin or, as Mark Twain called him, “that adventurous ass." It turns out that Blondin, widely considered to be the greatest tightrope walker of all time, had crossed the treacherous waters of Niagara Gorge on a tightrope several years before Leslie’s pancake crossing. And he too had carried a stove on his back though, like the good Frenchman that he was, Blondin prepared an omelet.

And that wasn’t all. In a series of crossings, each more unhinged than the previous, Blondin continued to push the tighrope envelope.

First, he stopped halfway to take a picture of the crowd.

Then he walked across on stilts.

Why not a chair? No idea how this one worked.

He even made his poor manager come along.

After learning all this, I figured Leslie’s story was probably just a creative local retelling of Blondin's exploits. But digging a little deeper, I found out that Leslie did indeed exist, and he even had a first name—Harry. Fittingly, he was known as the American Blondin. He, too, had crossed the Niagra Gorge, albeit six years after Blondin.

In 1876, Leslie had just finished a walk in Richmond, Virginia, when a little girl who had been watching the show with her parents slipped and started rolling down the roof. Leslie managed to grab her just as she came to the edge, but his foot got stuck in his rope, and he slipped and hit his head. Thankfully, Leslie managed to deliver the girl safely to her parents, but the blow he suffered was seen as the turning point in his slow descent into madness.

On April 22nd, 1884, the former funambulist was arrested and sent to the Flatbush Insane Asylum after attempting to walk across an imaginary tightrope out his window on Meserole Street in Greenpoint and threatening a stranger with a knife. A search of his apartment revealed a tightrope strung from one room to another with a jumble of old mattresses beneath. One week later, he was dead.

DANGERVILLE

Somewhere in the 19th century, Highbridge acquired the nickname “Dangerville.” According to McNamara’s Old Bronx, the name may have come from the reputation of the Irish, who accounted for the majority of the neighborhood’s residents.

McNamara has a better explanation, though. There was a wealthy landowner who decided his grand estate overlooking the Harlem River needed a name. He hired a blacksmith to forge four-foot-tall wrought iron letters spelling out the name “GARDEN VILLA.” Unfortunately, something was lost in translation, and the metalworker substituted the final “A” with an “E.” The landowner wasn’t about to name his estate GARDEN VILLE, so he left the letters stacked on his lawn while waiting for the new vowel.

The next night, some locals with a knack for witty anagrams snuck in and set the letters up in a prominent river-facing location. The following day, everyone traveling by train or on the river was treated to a glimpse of what would become the neighborhood’s new nickname—DANGERVILLE.

JOKER

As I walked around the neighborhood last week, a black van came to a screeching halt just a few yards ahead of me. The doors swung open, and a cadre of well-heeled tourists emerged. I noticed another group of camera-toting tourists eagerly walking from the opposite direction. When I rounded the corner, I realized what they had all come to see.

The Bronx is famous for its step streets, the vertiginous staircases tucked between buildings which supposedly make the borough’s grueling inclines a little more manageable for pedestrians. Never mind that they are often dark, littered with garbage, and nearly impassable in the wintertime. These days, the most famous step street, and the reason all these tourists were converging on the west Bronx are the stairs at West 167th Street that connect Shakespeare and Anderson avenues.

The puddle-splashing, crotch-thrusting choreography of Arthur Fleck, played by Joaquin Phoenix, has inspired thousands of people from all over the world to ascend the “Joker Stairs” and attempt to recreate the same moves—with varying degrees of success.

This previously seldom visited corner of the Bronx has succumbed to what sociologist John Urry calls the mediatised gaze, a form of tourism predicated around the desire to relive scenes from popular media. Other people call it meme tourism. Locals who actually use the stairs to get around simply call it annoying.

“I think the way a lot of us feel is, listen, like, keep your Instagram posts outside of the Boogie Down,”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

From what I could see, none of the visitors lingered and spent time (or money) in the rest of the neighborhood. Once the obligatory photo was taken, the tourists headed back to their idling van and sped off, probably too busy uploading their #jokerstairs photos to Instagram to even look out the window.

ABU TALIB

My first visit to Highbridge was over a decade ago when I was working with the Design Trust for Public Space on a commission to photograph the city’s urban agriculture movement. I was free to explore the city and photograph what I found, but was given a specific list of community gardens and farms they wanted me to visit.

One of those, the Taqwa Community Farm, is a half-acre community garden started by Highbridge local Abu Talib and a group of neighborhood residents in 1992. They transformed a vacant lot at 164th Street and Ogden Avenue into a lush and productive garden that yields an estimated 10,000 pounds of produce annually.

Despite some misgivings about teddy bear apron, Abu, who turned 90 this year, was kind enough to let me take his portrait.

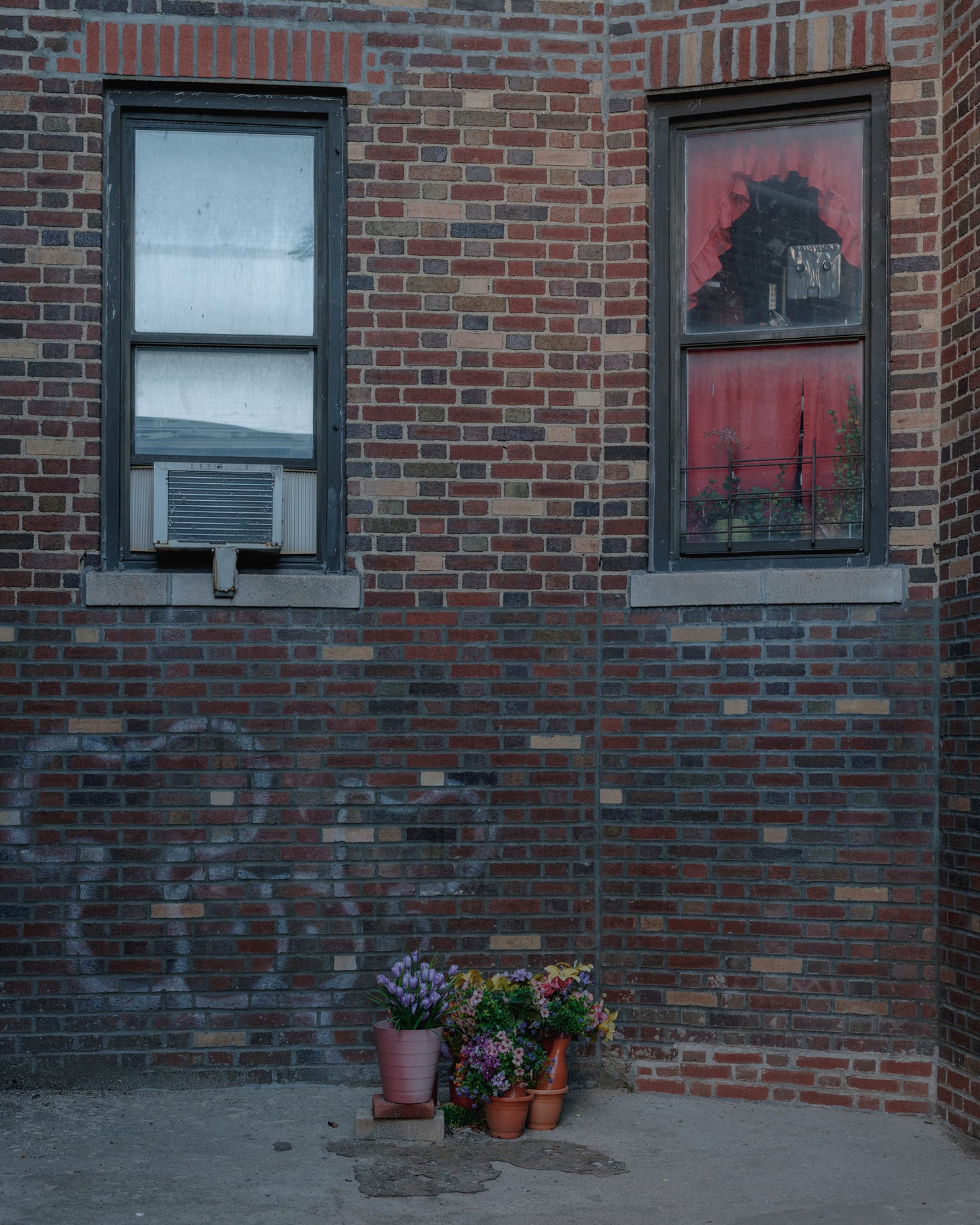

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

This week’s audio is a mix of street chatter, more ice cream truck jingles, and a free flowing fire hydrant outside of Taqwa Community Farm. It ends with a trip down the Joker stairs. Since my last visit was quite early in the morning, the stairs were blissfully empty, nary a Joker fan or influencer to be found. To make up for it, a resident of one of the apartments overlooking the stairs was blasting AratheJay’s Jesus Christ 2 (it was Sunday, after all) at ear splitting levels. I imagine the massive window mounted speakers are put to good use when the stairs get particularly crowded.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

Looking at the plans and old photos of High Bridge reminded me of Joel Sternfeld’s evocative photographs of the aqueducts in the countryside outside of Rome. These Roman ruins inspired the design of the Bronx aqueduct as it crossed the Harlem River. An excerpt from Joel’s introduction to his 2019 book, Rome After Rome, talks about how the Romans were inspired by their own designs and gives a little insight as to why the High Bridge is still standing.

Monuments in the Campagna endured because they were functional objects to begin with and thus built to last (which is not to say that aesthetics were ignored: sometimes an aqueduct was built in ancient Rome in the style of one built 200 years previously because the earlier one was considered charming).

Aqueducts were largely underground pipes in the mountains but when they marched across the final kilometers to Rome they came above ground and maintained the perfect incline to keep the water moving downhill. The trick was to keep the water in motion, but not so fast that rocks and stones which inevitably fell into the water channel would tear it apart, and also so that the water did not burst the pipes when it finally arrived in the city. Approximately three meters of descent for every 1,000 meters of length was the slope that did the trick, but how the Roman engineers achieved this without computer-aided design is wondrous.

Joel’s pictures of these crumbling marvels, luminous and suffused with the unique light of Rome, are themselves wondrous.

NOTES

A dance critic’s take on Joachim Phoenix’s dance moves in the Joker.

Here is a gallery of vintage tightrope walkers, including Blondin and Harry Leslie. Wire Walkers and Dare Devils

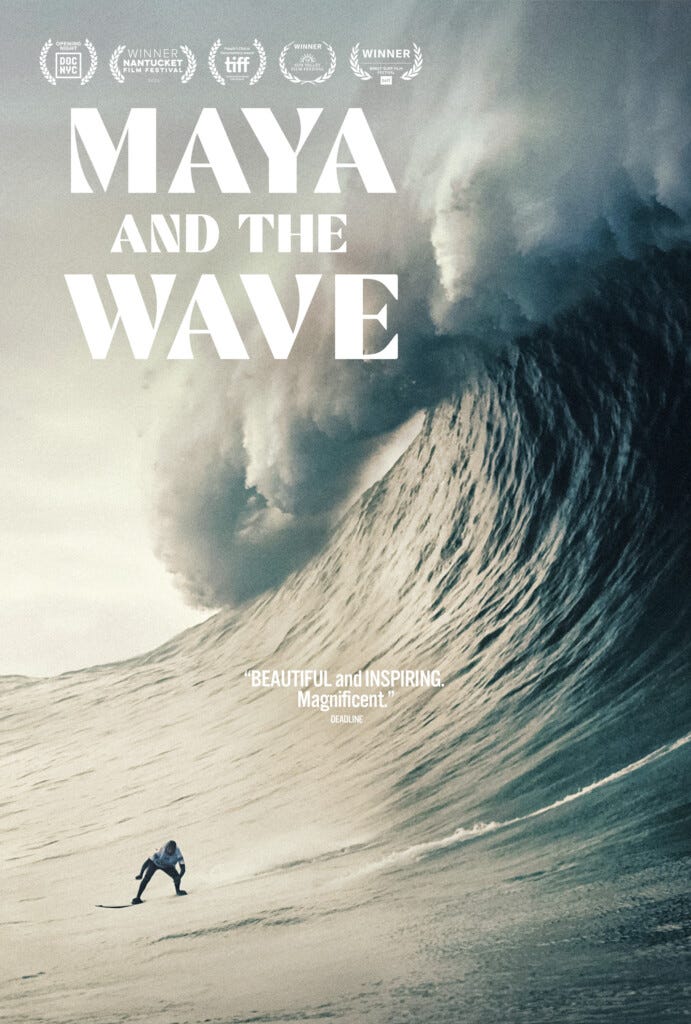

Speaking of daredevils, my friend Stephanie Johnes’ documentary, Maya and the Wave, is having a week-long run at the Village East theater starting tomorrow, Friday 9/13. The documentary is a behind the scenes look at Brazilian surfer Maya Gabeira, one of the first women to break into the male dominated world of big wave surfing. Stephanie spent more than a decade making the film with Maya. If you live in NYC, go see it! SHOWTIMES AND TICKETS 5/5 stars.

Above, I shared a tiny section of The City of New York map published by Galt & Hoy in 1879. This remarkable map, illustrated by Will Taylor, was the first genuine attempt at producing a vanishing perspective map of the city, including every road, pier, and building in Manhattan at the time. Only a handful of copies of the map exist. The Library of Congress, New York Public Library, and the New York Historical Society each have a copy. One of the only other copies was sold and hung in an office in the World Trade Center a week before 9/11/2001. Ironically, the office of Galt & Hoy was on the same plot as the old 4 World Trade Center.

You can download a full resolution (6’!) copy of the map from the Library of Congress website.

Wow this issue about Highbridge truly had everything - poor water quality, Poe mention, free pancakes, misspelled signage, tourist stairs, and a "where's Abu Talib". Absolute :chefs-kiss:

Abu Talib doesn’t look a day over 50! Eat your greens kids!