And what is that you smell?

Oh, that!...It is the old Gowanus Canal, and that aroma you speak of is nothing but the huge symphonic stink of it, cunningly compacted of unnumbered separate putrefactions. It is interesting sometimes to try to count them. There is in it not only the noisome stenches of a stagnant sewer, but also the smells of melted glue, burned rubber, and smoldering rags, the odors of a boneyard horse, long dead, the incense of putrefying offal, the fragrance of deceased, decaying cats, old tomatoes, rotten cabbage, and prehistoric eggs.

Thomas Wolfe, You Can't Go Home Again, 1940

I’m currently out of town with my family. So, when I began writing about this week’s neighborhood, I felt a little disconnected from the city. Fortunately, just as I was getting started, I was thrown into a situation that brought me right back.

Since arriving, the house we are staying in has been having some strange plumbing issues: slow-draining toilets, phantom gurglings, and the occasional sulphuric whiff. Then, on Saturday afternoon, it all came to a head.

The large center drain in the middle of the garage was going through an identity crisis of sorts and had decided to start sending things up rather than down. And by things, I mean raw sewage. As disgusting as this all sounds, it put me in the perfect frame of mind to write about this week’s neighborhood. Gowanus.

The Brooklyn neighborhood, situated between Wyckoff Street, Fourth Avenue, the Gowanus Expressway, and Bond Street, gets its name from the Gowanus Canal, the much-maligned arm of New York Harbor renowned for its pungency, a fetid mix of raw sewage and illegally dumped chemicals that have been accumulating for well over a hundred years.

Eventually, with the help of a plumber and a 300-foot snake, the drain started flowing properly, and I began the long and tedious process of cleaning the garage.

In 2010, the EPA embarked on a similar task when it designated the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site. To clean the canal, however, would take considerably more than a snake, a broom, and some bleach. A plan was proposed to build two enormous overflow tanks to address the sewage and begin dredging the over 600,000 cubic yards of cancer-causing coal tar at the bottom of the canal. As of today, the project is more than six years behind schedule and is estimated to cost $1.5 billion, a 19-fold increase over the initial $78 million projection. While the tanks have not yet been built, thousands of new apartment units have.

GET YOUR FREEK ON

Gowanus wasn’t always the oil-slicked, sewage-filled body of water it is today. Back in the days before it caught gonorrhea, it was a pristine creek fed by freshwater streams flowing through the tall stands of salt marsh grass, one of the choicest spots in all of Breukelen. It was so nice that the Dutch, after negotiations with Lenape chief Gauwane, made it one of the first settlements on what was then known as Long Island.

The Dutch know a thing or two about manipulating waterways, and by the middle of the seventeenth century, they had drained parts of the marsh and dug several ponds alongside the Gowanus Creek to power their tide mills. When full, the ponds would be closed off from the creek by a gate. Once the tide was low enough, the miller would open the gates, and the energy generated by the water flowing out would turn the mill stones.

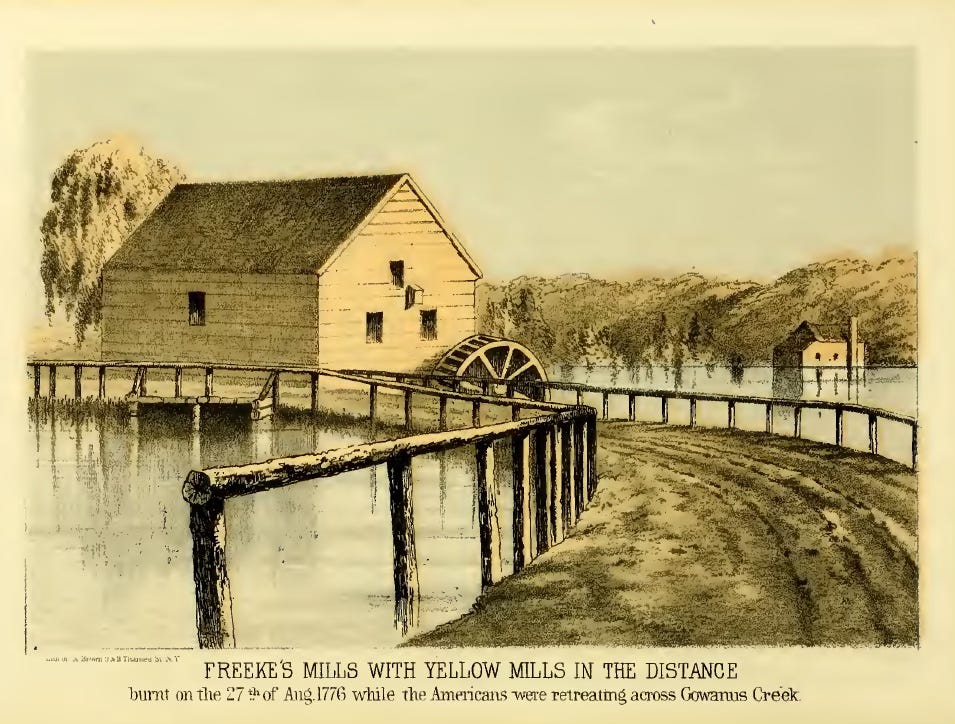

Around 1660, Adam Brouwer, a mercenary soldier from the Dutch West India Company, built a mill on the banks of the Gowanus Creek. The tide mill, later renamed Freek’s Mill, was the first in New Netherland. Other mills like Denton's and Cole’s followed suit and soon, Gowanus was a hotbed of grain grinding activity.

To transport the vast quantities of flour, cornmeal and ground ginger these mills were producing, boats had to undertake a rather treacherous journey around the Red Hook peninsula through the Buttermilk Channel to lower Manhattan. In 1664, Brouwer successfully petitioned to carve a channel through the marsh directly to the East River, creating the first iteration of today’s canal.

Besides the ceaseless turning of the millstones, things remained pretty quiet in Gowanus for the next hundred years or so. Dutch farmers took advantage of the fertile soil in the creek basin to grow acres of tobacco, wheat, and corn.

There was also a robust oyster pickling industry, with numerous accounts of dinner plate-sized oysters being pulled from the creek. Personally, the prospect of swallowing a foot-long pickled oyster is scarcely more appetizing than consuming a cup of the so-called black mayonnaise found at the bottom of the canal today. Still, the fact that the bivalves could live long enough to reach that size is indicative of the water’s once pristine condition.

MARYLAND 400

The Gowanus Creek played an outsized role during the Battle of Brooklyn (aka the Battle of Long Island). On August 27th, 1776, British troops landed on Long Island and surrounded the significantly smaller American Continental Army.

Eventuallly, all the action funneled down to the creek. A group of soldiers known as the Maryland 400 were positioned in Gowanus Heights (now Park Slope) and were able to hold off the British troops while the rest of the American forces escaped across the creek. The natural barrier of the creek bought General Washington enough time to organize a further retreat across the East River. All the mills and the bridges that crossed the creek were burned.

After the war, the land around the creek remained largely unspoiled, with the 1,758-acre Gowanus watershed serving as a natural bulwark against the rapidly growing city around it.

Of course the inevitable march of progress soon put an end to that.

SANITARY EVILS

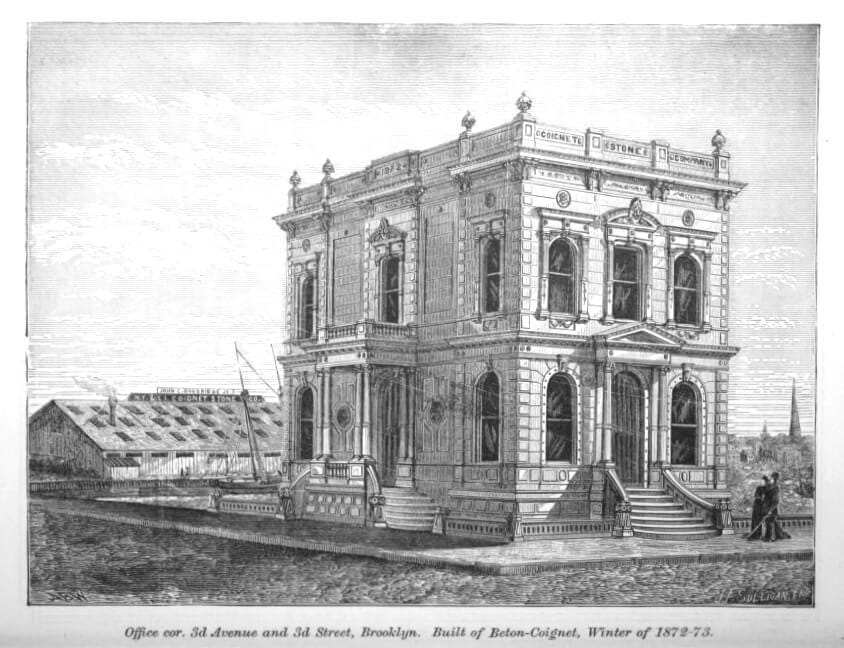

By the end of the 19th century, thanks to the efforts of railroad mogul Edwin Litchfield and his Brooklyn Improvement Company, the creek had been transformed into a 1.8-mile-long canal. It soon became the nexus of Brooklyn’s commercial shipping activity. At its peak in the early 1900s, over 100 boats a day made their way through the Gowanus, making it the busiest industrial and commercial canal in the country.

The shores were lined with the crème de la crème of toxic polluters—tanneries, paint and ink factories, chemical plants, oil refineries, and coal yards, all trying to outdo each other in the amount of industrial waste they could dump into the canal.

Brooklyn had the first sewer system in the country, and, while in theory the pipes were supposed to carry waste all the way to the East River, most of the sewage from the surrounding neighborhoods was diverted into the canal. In Brooklyn’s combined sewer system, household sewage and stormwater shared the same pipe. With the loss of the absorbent buffer the wetlands once provided, stormwater accumulated quickly, and the system was frequently overwhelmed.

During particularly bad storms, the runoff backed up into the drains, flooding basements and local streets. To this day, Gowanus still experiences some of the worst flooding in the city.

An 1876 report in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle recounted the “sanitary evils” engendered by the new canal, saying, “Its waters are becoming more and more obnoxious every year, the sides of the docks are becoming encrusted with filth, and carcasses float there for weeks.” Sandbars of raw sewage would frequently form at the mouths of the sewer outflow tunnels. Locals began referring to the body of water ironically as Lavender Lake.

Another article detailed the 9,187 pounds of solid waste and 10,682 gallons of liquid waste being deposited into the canal daily. Bills were proposed “for the closing up of that putrid ditch,” but the fat cats who depended on the canal for their businesses had enough money and influence to see that they never got passed.

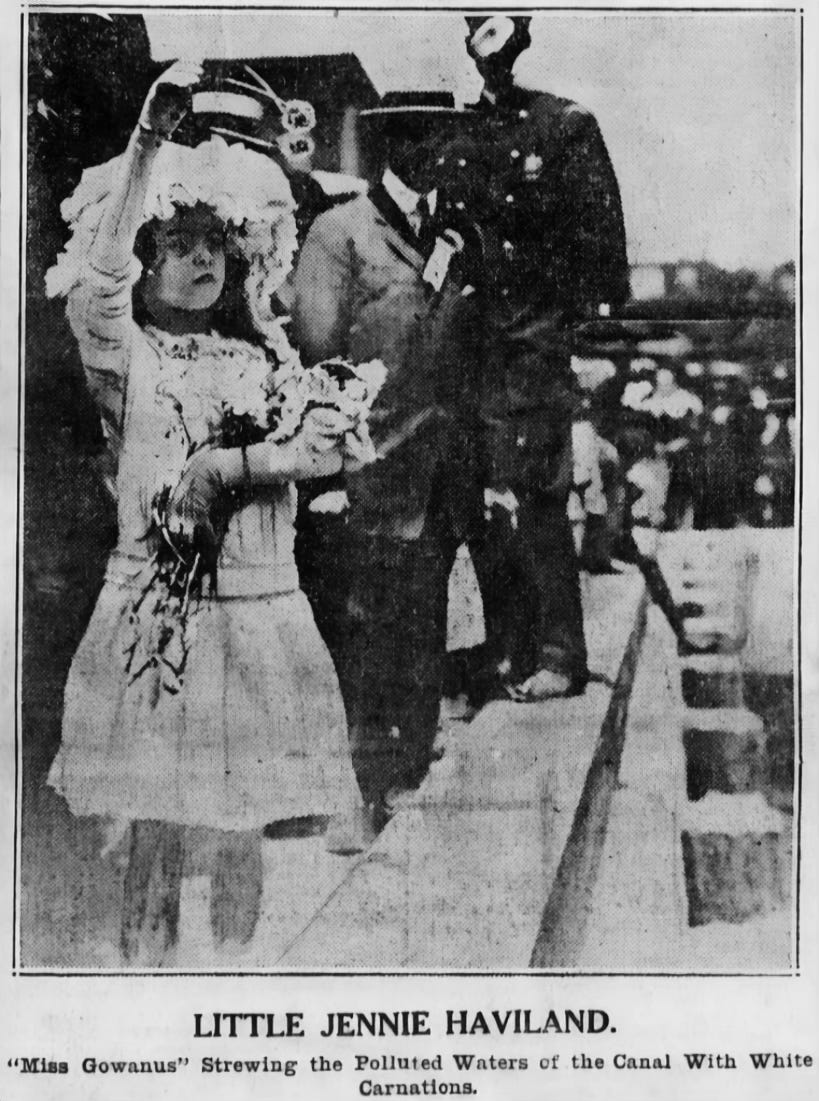

In 1911, with much fanfare, the city opened a 12-foot-wide flushing tunnel that employed a giant propellor to pull in cleaner water from the Buttermilk Channel over a mile away.

The tunnel finally got the water circulating, ameliorating at least some of the pervasive smells.

RIVAL UNDERTAKERS

A few years later, in 1915, while heaving a large rock, eight-year-old Tony Studo lost his balance and fell into the canal, quickly succumbing to the toxic waterway. Two local undertakers, John Romanelli and Gaetano Mangino, quickly arrived on the scene.

The bereaved parents entrusted Mangino with their son’s body. Romanelli, whose operations were a couple of blocks closer to the scene, took umbrage with the choice and let his rival know his displeasure. Soon, 150 locals, many of them armed, were brawling in the streets over the right to bury the 8-year-old.

The crowds were so thick that it took the cops over an hour to get to the center of the melee. There, they found Mangino lying in the gutter. He had been shot and stabbed twice. Romanelli had merely been grazed by a bullet.

Inciting a riot over dibs on a burial was the tip of the iceberg for Romanelli. Just three years later, he was arrested for stealing several barrels of wood alcohol, a substance used as embalming fluid, and reselling it (for over $23,000) as fine French Whiskey. In what was known as the Christmas Eve Massacre, nearly a hundred people throughout New England died from ingesting Romanelli’s doctored booze. Since all the deaths occurred out of state, Romanelli only served two years in New York prison on the charge of grand larceny.

BLACK MAYONNAISE

When the Gowanus Expressway opened in 1951, followed by the Verrazzano Bridge in 1964, trucks became the preferred method of transporting goods in and out of the city, and traffic on the canal fell dramatically. Then, the advent of container shipping requiring larger, more modern ports made the shallow waters of the Gowanus wholly obsolete. Regular dredging of the canal stopped in 1955, and in the mid-1960s, the propellor that powered the flushing tunnel broke. It would remain inoperable for the next thirty years.

In the seventies, several community groups spearheaded efforts to clean up the canal. In 1987, the Red Hook Wastewater Treatment Facility (confusingly located in the Brooklyn Navy Yard) significantly diminished the amount of raw sewage going into the Gowanus. In 1999, a new and improved flushing tunnel was put back into action, capable of sending nearly 300 million gallons of oxygenated water through the waterway each day.

Then, when the EPA designated the Gowanus a Superfund site in 2010, the process of dredging the 10-foot-thick deposit of sediment at the bottom of the canal began. The sickening sludge, colloquially known as Black Mayonnaise, is a toxic mix of coal tar, motor oil, raw sewage, and whatever else has found its way to the bottom of the canal.

Whether or not all the mayo can ever be cleaned out is up for debate, but that hasn’t slowed down developers’ efforts to make Gowanus the “Venice of Brooklyn.”

The area was rezoned in 2021. Despite findings of high levels of cancer-causing chemicals like trichloroethylene, the continued presence of coal tar in the soil, and strong community opposition, construction is underway on over 8,500 new apartments, including 3,000 units of affordable housing.

The scale and pace of new construction in the neighborhood are surreal. While addressing the city’s pressing need for new housing is crucial, hopefully, it doesn’t overshadow the necessity of remediating decades of severe environmental contamination.

SIGHTS AND SOUNDS

I need to revisit this week’s audio, hopefully from a canoe or something that gets me closer to the water. For now, it's just your basic city soundtrack: sirens, traffic, and unintelligible yelling.

FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHER

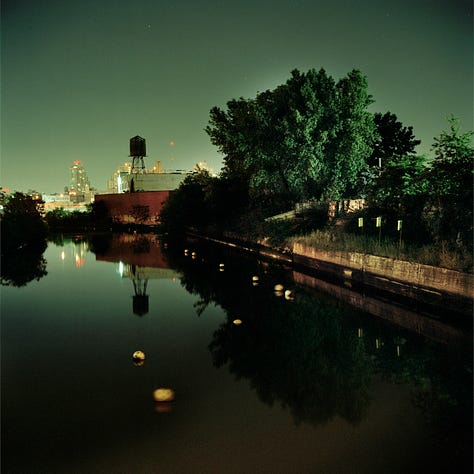

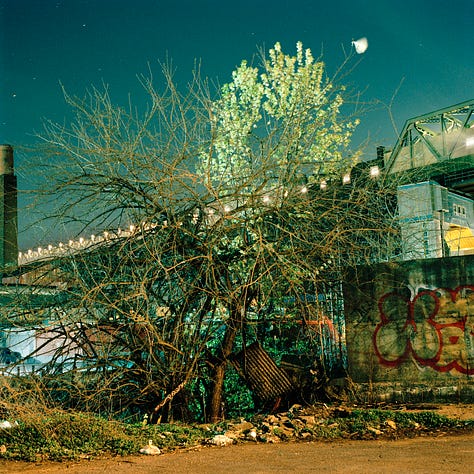

This week, I am featuring the work of Miska Draskoczy. In 2012, Miska started documenting the nocturnal landscape around the Gowanus for a project called Gowanus Wild. I’ve always been drawn to the persistence of nature in the face of urbanity that Miska captured so well.

My vision for Gowanus Wild is to illustrate a personal exploration of nature and wilderness in the paradoxical setting of a contaminated industrial environment. As the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn has been declared a federal Superfund cleanup site and seen over 150 years of continuous industrial use, one of my aims with the series is to show just how tenacious nature can be in the face of such grave environmental destruction.

You can order Miska’s book here.

ODDS AND END

There have been several large mammals who have found their way into the Gowanus including a dolpin in 2013, Sludgie the Whale in 2007, and a Sperm whale in 1928. Unfortunately, none of them made it out.

The Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club is a volunteer organization “dedicated to providing waterfront access and education about our estuary and shoreline neighborhoods.” They offer regular free self-guided Gowanus canoe trips, including one this weekend.

I highly recommend Lavender Lake, Allison Prete’s 1999 Errol Morris-esque documentary on the Gowanus.

Joseph Alexiou’s Gowanus: Brooklyn's Curious Canal was invaluable in writing this week’s newsletter

This recent Curbed piece describes the current situation in Gowanus as “maybe a harbinger of the city’s increasingly dissonant future: a rising mix of green luxury and desperately needed affordable housing alongside silent toxins emanating from the ground.”

Want to serve Black Mayonaise at your next Gowanus-themed dinner party? Here is a recipe.

Then you can put on “When You Get Caught Between The Moon And Boston Harbor: The Best That Black Mayonnaise Could Do 1991-2008” if you really want to freak out your guests.

I’ve always loved this painting of the Gowanus by Randy Dudley

It doesn’t get much more Brooklyn than Gowanus’ Public Records, an immersive sound space/vegan restaurant/record store/music venue. 5 Stars

Buckwheat baguette at Runner & Stone. Also 5 Stars

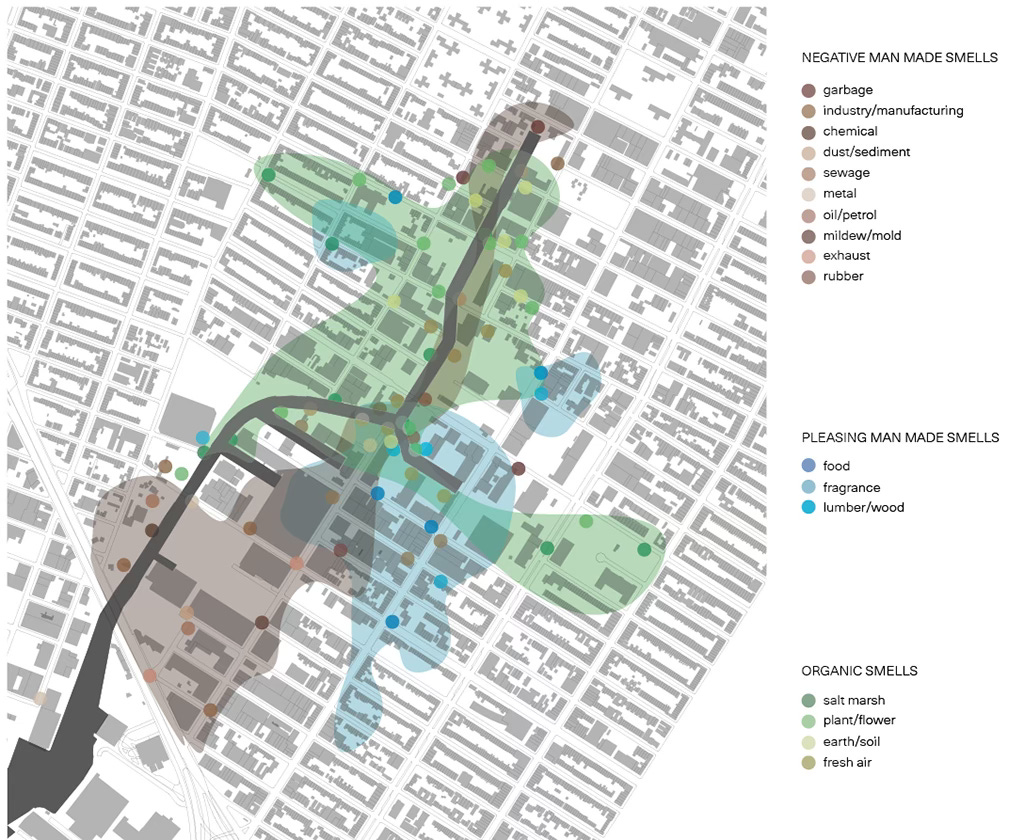

Olfactory map of the neighborhood from Annie Barrett Studios

Thanks Laurie! Such a great doc!

It always hurts to see what the land in these neighborhoods looked like before European colonists entered the picture. I wanted to share this link also in case anyone is curious about some of the current efforts to transform that area to resemble a place more natural and inhabitable for wildlife https://gowanuscanalconservancy.org/